08 Oct 14 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, Romania

In November, Romanians are set to head to the polls to elect a new president from a field of 14 candidates during two rounds of polling. But one important participant, the National Audiovisual Council of Romania (CNA), will be sidelined as it loses its legally mandated quorum.

According to the CNA’s website, its role is to “ensure that Romania’s TV and radio stations operate in an environment of free speech, responsibility and competitiveness.”

While the first round of voting is set to get underway on 2 November, the CNA’s quorum of eight will be halved on 4 November when four members of the council step down at the end of their terms. If no candidate wins a majority in the first poll, the top candidates will compete in a second round on 16 Nov.

“Without a quorum, the CNA cannot function, and thus it cannot sanction the eventual abuses of television or radio stations during the election campaign,” said Narcisa Iorga, a CNA board member. Iorga believes politicians will benefit from this, as it is in their best interests to have an inactive CNA. Television stations will also use the situation in their favor, though they are already accustomed to breaking the audiovisual legislation, she added.

According to some members of the council, it could be January before the CNA regains its quorum and the ability to make decisions on issuing sanctions, well after the election campaign and the two rounds of voting.

The CNA is Romania’s only regulatory body overseeing television and radio programmes. In its watchdog role, the regulator ensures that legislation governing programming is respected. It’s a key role in a country where television is the dominant media among the population. Political parties and interest groups use the country’s live television shows to get their message across to the public.

By law, the CNA is supposed to have 11 board members. To maintain a quorum, eight members need to be present at the proceedings. The members, who have a mandate of six years, are nominated by the senate (three members), the chamber of deputies (three), the president (two), the government (three), and are confirmed by the parliament.

This is where politics comes into play: the parliament, controlled by a coalition led by the party of Victor Ponta, the prime minister who is the best-placed candidate at the presidential elections, did not vote to confirm the new members before the parliamentary vacation began. Therefore in less than a month, the CNA will have only seven members, one member short of the quorum.

Not having enough members to be able to take decisions is nothing new for the regulatory body. When there are politically sensitive issues on the table, some of its members usually go on a vacation.

For example, on 9 October a number of complaints against the Antena 3 news television will be debated, but it is more than likely that will be no quorum. Two CNA members are currently on vacation, and another two just announced their absence, wrote Iorga on her Facebook wall.

Media violation reports from mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Penal code change could ensnare journalists

Falun Gong practitioner detained during interview

Journalists denied access to government building

Director of public television receives “warnings”

Jurnalul National editor assaulted and threatened

This article was published on 8 Oct 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

06 Oct 14 | China, News and features

From left to right: Harvey Tomlinson from MakeDo Publishing, Chen Xiwo and translator, Nicky Harman at English PEN. (Photo: Aimée Hamilton)

Chen Xiwo, described as “one of China’s most outspoken voices on freedom of expression for writers” by Asia Sentinel, has spoken about how he challenged the Chinese government’s decision to censor his latest book ahead of its launch in English.

The Book of Sins is a collection of seven novellas exploring controversial topics including rape, incest and S&M and examine the links between sexual and political deviance.

A heavily censored version of the book was published in China, in which parts of the text, including an entire novella, were removed.

Xiwo launched a case to sue China’s customs agency in an attempt to find out why his book, which was published in full in Taiwan, had been confiscated when it arrived in China in 2007. He was originally told that it was its dark and pornographic nature that had led to it being banned in its complete form.

In an unprecedented move, Xiwo took the customs office to court. He said in the history of the People’s Republic of China, since 1949, there has never been a case of a writer suing for not being allowed to publish a book.

Originally when the court hearings got underway the domestic news outlets were able to report on the progress until the propaganda ministry sent out an order forbidding further coverage.

During a meeting today run by English PEN at the Free Word Centre in London, Xiwo said: “These days these kind of orders are usually just made by phone call, so they won’t send an email where there’ll be a record, they do it by phone.

“This makes it even harder to get to the bottom of who’s banning what and why they’re doing it, because there’s no record.”

Chen Xiwo (Photo: Aimée Hamilton)

Eventually the court ruled that Xiwo’s case was a matter of national security, which ended further questions on the topic. In a blog entry for Free Word, Xiwo writes: “The Book of Sins had been impounded because it was deemed a threat to ‘national security’. In fact, they completely dropped the charge of obscenity. That meant they did not have to divulge any further information, or even say who had made the final decision.”

Xiwo’s book has now been translated into English by prolific translator Nicky Harman, who said: “Chen is a highly moral writer in my view. The sex and the small amount of violence, it’s never gratuitous. He really focuses on feelings, he has a good attitude towards women, he’s not misogynistic.”

One of the most provocative stories within the book, I Love My Mum, is about a disabled man who strikes up an incestuous relationship with his mother which ultimately ends in him murdering her. The novella is metaphorical of Chinese society and remains banned in the country.

When asked if he would challenge the banning of his books again, Xiwo said that it is inevitable future books of his will be banned, but he cannot launch a case for every one of them.

Although Chen Xiwo has written 10 books, he says only six or seven of these have been published in their complete form. The Book of Sins has won an English PEN award. Chen Xiwo will be launching the English translation of the book at Waterstones Piccadilly, tomorrow 7 October, at 7pm.

This article was posted on 6 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

03 Oct 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

(Photo: Banksy.co.uk

There’s a grand tradition of satire and mocking the great, the good and the very ordinary in Britain. From Swift’s Modest Proposal to Not the Nine O’Clock News, and from TV’s stunning Spitting Image to the magnificent everyday newspaper cartoons by masters such as Martin Rowson and The Independent’s own Dave Brown.

So as a nation that has grown up on a diet of cartoons and caricatures seen over our morning boiled eggs why should we worry about Banksy taking artistic aim at the current debate on immigration, and poking fun at it in a mural on a seaside town’s walls? Well we shouldn’t, of course, because we have grown up on that very same diet of mocking and magnifying debates using caustic comedy, and Banksy’s murals are just modern manifestations of that.

In his mural are some grey pigeons, carrying placards, and down there we have a colourful exotic bird, clearly one that has migrated here, possibly for the summer, and the grey ones are not keen. One of the grey birds holds a sign saying: “Go back to Africa” and another holds “Keep off our worms”.

Here, in the mural, are some of things people say about immigration on the streets of Clacton, and on the streets of other towns or cities. And what this mural is showing are some of those ordinary views. To me what it is suggesting is: “What next? Are we going to stop birds migrating here for the summer?” Anyway, whether you think it is funny or not, you surely can’t deny that it is magnifying some of the debates we are having about immigration in these past few months, and no doubt in the next six as we approach the general election, and locally in Clacton-on-Sea, in its upcoming by-election.

Swift suggested the Irish should eat their babies; Spitting Image had members of the cabinet spitting out vegetables. This is taking an idea or discussion that is in the public arena and magnifying it, sometime to outrageous proportions, to poke fun and to stir up debate over the cornflakes, and to make people think a bit harder.

Caricature has historically been able to point fingers, and make fun and spike discussion in ways that editorials in newspapers don’t reach; a sort of Heineken effect.

Tendring District Council has explained that it has a rapid reaction force on seafront graffiti, and when just one person complained and found the language racist, its anti-grafitti team was dispatched, agreed with that the language could be seen that way, and acted within “their remit” to get rid of it. Their spokesman said the team did not have to consult and no one knew this was a Banksy. Apparently it would be fine if Banksy wanted to come back and do something else though.

Sadly, all it takes one person to think something is racist, and we paint over a great bit of current commentary on intolerance, even though as lawyer Tamsin Allen outlines “political speech is given higher protection by the European court during an election period than at other times”. The British have a long and glorious history of satire and humour. And we should never feel the need to paint over things that challenge our views. Challenge and debate make us stronger, and we should grasp that freedom to debate as hard as we possibly can.

A version of this article was originally posted on 2 October on Independent Voices

03 Oct 14 | Campaigns, Statements

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has proved itself a vital last line of defence in protecting free speech in the UK, not least in defending a free press.

It was the European Court that ruled Britain had acted unlawfully in gagging newspapers over Spycatcher, it was the European Court that ruled in favour of a journalist punished by the UK courts for refusing to reveal a source, and it is the court in which UK legislation on mass surveillance is currently being challenged to ensure continued protection for journalists‚ and their sources.

Under extensive plans mooted by the UK’s Conservative Party, to be introduced if it won the next election, it claimed ECHR judgements would only be advisory, rather than binding. Final rulings instead would be made by the London-based Supreme Court. The party also pledged to write a new British Bill of Rights, which would reduce or qualify existing rights. They have also suggested the UK government would withdraw from the European Convention if parliament and the British courts did not have the power to overrule ECHR judgements.

Index believes that any UK government that attempts to undermine the ECHR would provide countries with appalling human right records a ready-made excuse to ignore the internationally recognised standards that the court represents.

03 Oct 14 | Bahrain, Bahrain Statements, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

Nabeel Rajab, a prominent Bahraini human rights activist and Index award winner, has been detained for seven days while being investigated for claims that he offended the Ministry of Interior over Twitter.

Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg said: “Index is deeply concerned that the UK government has done little to press Bahrain to improve its human rights record. Instead the UK talks repeatedly of improvements in the human rights system in Bahrain when it is clear that rights such as freedom of expression are not being respected.” Index is writing to UK MPs to raise the case of Rajab.

On 1 October, Rajab, president of the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR) and director of the Gulf Centre for Human Right (GCHR), was summoned by the cyber crimes unit of the Criminal Investigation Directorate. He is alleged to have “denigrated government institutions” on Twitter, according to the Ministry of Interior. Rajab was released in May after two years in prison on charges including making offensive tweets and taking part in illegal protests.

Rajab “has been targeted with repeated arrest and detention because of his work in the field of human rights” and “the government’s aim is to hinder his advocacy work both inside and outside of Bahrain”, said BCHR, Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) and the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD).

The arrest came shortly after Rajab’s return to Bahrain following an international trip to raise awareness of human rights violations in his country. He was calling for the release of human rights activists — and father and daughter — Maryam and Abdulhadi Al-Khawaja. Maryam has since been released on bail, her travel ban lifted and trial postponed until 5 November. Abdulhadi continues to serve the life sentence handed down to him in 2011, after playing a prominent role in the country’s pro-democracy protests that year.

While in London, Rajab told Index about the human rights and free speech situation in Bahrain, saying that “at least 50,000 people” had been in and out of jail in the past three months alone, “just for practising their right to freedom of assembly, freedom of gathering, freedom of expression”.

“It is time for Bahrain’s rulers to stop harassing human rights defenders and silencing free speech, and live up to their international obligations – including those they pledged again to uphold as part of the UN Universal Periodic Review just last month. Please, let our colleagues go free. Free Nabeel Rajab and drop the charges facing Rajab and the Al-Khawajas, ” GCHR said in a statement.

Correction 10:30, 3 October: Due to a typo, an earlier version of this article used the number “50,0000” instead of “50,000”.

This article was posted on 2 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

03 Oct 14 | Events

Index on Censorship is delighted to announce the third in a series of online conversations about artistic freedom of expression in Wales.

Index on Censorship is delighted to announce the third in a series of online conversations about artistic freedom of expression in Wales.

This conversation forms part of our ArtFreedomWales programme looking at how artistic freedom is regarded, debated and promoted across the arts sector in Wales – in the press, by artists, by the public, by funders and policy makers.

Young Artists in Wales – opportunities and obstacles to expression?

Online conversation with:

- Chelsey Gillard – Critic

- Sian Rowlands – Dancer

- Elgan Rhys – Actor & Writer

- Cerian Wilshere-Davies – Mess up the Mess Youth Theatre Group

- Melody Patry – Senior Advocacy Officer, Index on Censorship

When: November 3rd 14.00

Where: Take part in the Google Hangout here

What are the issues in Wales? What are the opportunities? What are the obstacles? What has the right to freedom of expression got to do with Wales’ major cultural debates and policies: bi-lingualism, engaging young people and ethnically diverse voices, tackling poverty, maximising on new cultural infrastructure, having an international voice?

We want to hear from everyone producing and participating in the arts in Wales who has something to say about freedom of expression. You will be able to email and tweet questions to the panel during the discussion.

This is the third of four events on artistic freedom of expression in Wales that we are live-streaming, leading up to a national symposium – a Free Speech Hearing for Wales – at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff (27th November).

The first online conversation featuring leading artists from across Wales and the second online hangout which took place in Welsh are both available to watch here.

Arts Council of Wales supports this programme

02 Oct 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, United Kingdom

Supporters of Scottish independence protested against alleged BBC bias ahead of the referendum on 18 September (Image: Mishka Burr/YouTube/Creative Commons)

Benito Mussolini wrote romantic fiction. Of course he did. Maudlin sentimentality is at the very heart of fascism, which is why we should be keeping a closer eye on Mrs Brown’s Boys.

The Cardinal’s Mistress (or to give it its typically grandiose full title: Claudia Particella, Lamante del Cardinale, Grande Romanzo dei Tempi del Cardinale Emanuel Madruzzo) was written in the first decade of the 20th century, when the future dictator was still playing with socialism before he came up with his big idea. It was originally published as a serial in La Vita Trentina, the weekly supplement of socialist newspaper Il Popolo.

Reviewing an English translation of the work in 1928, Dorothy Parker, who admits to er, struggling with the book, dreamed of a scene “in which I tell Mussolini ‘And what’s more, you can’t even write a book that anyone could read. You old Duce you,’” before deadpanning, “You can see for yourself how flat that would leave him.”

It’s unclear whether or not Mussolini was left flat, or even read Parker’s New Yorker magazine review. But it’s possible to imagine that the negative review haunted him to the very end, that Il Duce spent his last days still pondering whether to write an angry letter to the New Yorker, pointing out that since Parker had admitted that she HADN’T EVEN FINISHED THE BOOK, it was a SERIOUS LAPSE of journalistic and critical standards to even run the review, and a sign of how a ONCE GREAT publication had been given over to cheap jibes and sarcasm instead of proper discussion of literary works [and so on, ad lamppostium].

One can imagine his supporters on Twitter, furiously @-ing the poor Parker: “Call yourself a journalist? #NewYorkerBias”, “MSM once again Misreprasents #IlDuce. #NoSurprise (@medialens)”, “So apparently this ‘Parker’ woman is actually a ROTHSCHILD? #BoycottNewYorker”, and so on and on and on and on and wearily on.

You know the kind of thing, because we see it every week now. The dull, thudding obsession with the idea that the media, or a section of the media is involved in some enormous conspiracy against you and your views, and subsequently the belief that that is the only reason not everyone shares your views.

The Scottish independence referendum was a case in point. Yes supporters became curiously obsessed with the BBC’s Nick Robinson and his apparent conservative sympathies. Now, Robinson, like many BBC hacks before him, (Andrew Marr? Socialist Organiser; Paul Mason? Workers’ Power; Jennie Bond? Class War), was politically active in his youth, rising to be president of the equal parts hilarious and horrendous Oxford University Conservative Association. This, plus a terse exchange between Robinson and Scottish Nationalist leader Alex Salmond over a media conference question Robinson felt Salmond had not answered properly, led to hundreds of nationalists converging on BBC Scotland’s headquarters claiming the BBC was biased against them and demanding, well, something.

This was bad enough, but they were egged on by Salmond himself, who said he thought there was “real public concern in terms of some of the nature and balance of the coverage”.

Calls for “balance” are almost always, in fact, calls for more-of-my-side and less-of-the-opposition. This was beautifully demonstrated by the number of complaints logged against the BBC in August about the most recent Israel-Palestine conflict. That month, 938 people complained that the BBC’s coverage was too favourable to the Palestinians, while 813 felt it the corporation was too favourable to the Israeli side. (Incidentally, in the same month over 350 people complained that the BBC had been too pro-independence in its broadcast of a Scottish referendum debate.)

The most embarrassing spectacle of the entire referendum came the days after the vote, when the nationalists had lost. The SNP sulkily decided they would bar right-wing, pro-union newspapers from the morning media conference. Salmond allegedly then tried to handpick which reporter from The Guardian would be allowed attend. The Guardian, doubly affronted by the ban on their press pack colleagues and Salmond’s demands upon it, rightly told Salmond they would skip the conference altogether.

The SNP are far from the only people to think they can demand good coverage and prevent dissent. Mark Ferguson, of the left-wing, trade-union-supported website Labour List, was recently informed that he would not be given a press pass for the Conservative party conference in Birmingham. It was only after other journalists raised their objections via Twitter that the Conservative party relented. It’s probably true to say that the Labour blogger’s coverage would not be the most pro-Tory, but that’s really not the point.

Meanwhile, in the wide world of sport, Newcastle United’s controversial owner owner Mike Ashley has decided that the Daily Telegraph’s Luke Edwards (and anyone else from the Telegraph, for that matter) will not be allowed near the club’s ground again, after Edwards reported rumours that Ashley may be seeking to sell the club.

There is an argument that Ashley generates enough bad publicity for himself without the assistance of apparently hostile journalists (Ashley recently caused confusion after telling a reporter with The i newspaper that club manager Alan Pardew would be “finished” and “dead” if Newcastle lost their next game), but that doesn’t make the move any less thin-skinned and censorious.

Football has form on this. Sir Alex Ferguson may have been the greatest manager of the modern era, but he was also so petty as to refuse to talk to the BBC for seven years after he objected to a documentary about his son aired by the national broadcaster.

Perhaps this tetchiness is what’s needed to get ahead, but it feels increasingly like a retreat from argument, and a retreat from the idea of open debate and a robust public sphere. We won’t accept arguments counter to our own, and if those arguments prove more popular than ours, it is not because ours may need rethinking. No, it is because the world is biased against us. We’re either being silenced by the metropolitan liberals, or censored by the public school Tory elites. Our public conversation is in danger of becoming a public whinge.

Correction 15:40, 2 October: An earlier version of this article stated that Paul Mason was in Workers’ Hammer.

This article was published on Thursday 2 October at indexoncensorship.org

01 Oct 14 | Campaigns, Statements

British Home Secretary Theresa May has proposed new laws that would ban extremists from TV and impose stricter controls on what can be said on the internet, in a speech at the annual Conservative Party conference. Index on Censorship is disturbed at these plans and their potential for stifling legitimate free speech.

It is unclear why further legislation is needed in this area: there are already laws on incitement to violence and hatred, and extremists can already be prosecuted under existing hate crime laws. The proposed banning orders would encompass a far wider group than at present and apply to any organisations deemed to be undertaking activities “for the purpose of overthrowing democracy”. That smacks of the McCarthy witch-hunts of the 1950s. Rather than focusing on terrorist or extremist groups who expressly incite violence, the new categories defined by May could include anyone who disagrees with the government.

Driving debate underground is not the answer in tackling extremism or terrorism. May’s proposals for additional powers to silence extremists are unworkable in their present form and will need serious vetting before they see the light of day. Index hopes that parliament will see the wisdom of using existing laws that May claims are already the toughest anti-terrorism legislation in the world, rather than introducing new laws that further erode our civil liberties.

01 Oct 14 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 43.03 Autumn 2014

An Egyptian man takes a photo of a large anti-Morsi protest in Tahrir Square, Egypt (Photo: Phil Gribbon/Alamy)

Imagine this: a journalist with her own news drone camera that can be sent to any coordinates in the world to film what is going on. Imagine a world where you had the ability to programme a whole set of drone cameras to go and film a riot, a rally or a refugee camp.

Imagine being able to set off your smartphone down a dangerous river, encased in a plastic bottle, to take photos that might prove the water is carrying disease or is not safe to drink. How about drone cameras that you can leash to your GPS co-ordinates to follow and film you or someone else? Those worlds should not be hard to imagine as they exist already, and, in some cases, those facilities are already being used by journalists.

The future of journalism is going to build on technologies we already have. But we must remember it isn’t really about the technology, but about what it can help us deliver. When the subject of the future of journalism is discussed it often turns to whizzy gadgets but the debate about whether the public ends up being better informed and better equipped happens less often.

The information superhighway, as the internet was once called, was supposed to give individuals amazing access to knowledge that they couldn’t access before, from historical documents to live video footage. And it has.

But the thing that most of us didn’t bargain for was that it would mean we had so much stuff coming at us. We no longer knew where to turn, our eyes and ears were full, a welter of “news” snippets became impossible to absorb, and as for analysis, well, who had time for that?

The reality of exciting new technology is that it is coming to the market at a time when the public appears to value journalists less, and can turn to Twitter or Facebook or citizen journalists to find out what’s going on in the world. Journalists; who needs them when we can find out so much for ourselves? It’s a reasonable question, and of course good and determined researchers can find out plenty of information for themselves, if they have hours to spend. But then again journalists have a whole set of tools and training that should mean they are better than the average member of the public at finding out facts and analysing reports as well as presenting the end results.

Journalists are trained and practiced at interviewing, asking the right questions and drawing out relevant pieces of information. These are rarely acknowledged skills but you have only to switch on a phone-in programme or watch a set of parliamentarians try to quiz a witness at a committee to know asking a good question is not as easy as it might seem. Knowing where to look for evidence and sources is not always so simple as putting any old question into Google either. Then there is analysing charts, graphs and tables; this should be a particularly valued set of skills. When it comes to recognising a story, then the good old reporter’s nose comes in handy. And writing up and compiling a story so that it makes sense and tells the story well is perhaps the most underrated skill of all. Good writing is sadly underappreciated.

With a toolkit like that, it is not surprising that governments around the world would rather journalists weren’t at the scene of a demonstration, or sharpening up their introduction of a story about a government cover-up. Perhaps that’s why governments around the world from the USA to China make it especially difficult, or particularly expensive, for journalists to get a visa. And that’s why journalists are targeted, watched, held captive, and in some horrific cases, such as with US journalist James Foley, murdered. Increasingly journalists are working on a freelance basis from war zones and conflicts. As our writer Iona Craig reports from Yemen, this can leave you exposed on two levels – without the protection of being a staff member of a huge news organisation, and without any income if you can’t file stories. That exposure to pressure, and possible violence, also affects bloggers operating as reporters, and is something that worries OSCE’s Dunja Mijatovic (interviewed in our latest magazine), who brought journalists from different countries together in Vienna last month to discuss what needs to be done.

Journalists are still needed by societies, what they do can be very important (although sometimes very trivial too). At the same time that job is changing. In this issue Raymond Joseph’s fascinating article shows how African newsrooms with little money are able to use low-cost technology such as remote-controlled drone cameras to monitor oil spills, as well as less-sexy-sounding data analysis tools to help reporters find out what is going on. He also reports on how newsrooms are working closely with citizen reporters to bring news from regions that were previously unreported. Work being carried out by Naija Voices in Nigeria, and by our Index 2014 award winner Shu Choudhary in India, shows how technology can help augment old-fashioned reporting, getting news to and from remote areas.

News reporting is also taking different forms to reach different audiences, as was brought home to me at the Film Forward conference in Malmö, Sweden, this summer, when US journalist Nonny de la Peña and Danish journalist Steven Achiam showed the audience how interactive news “games” and cartoon-style films are new forms of reportage. Achiam’s Deadline Athen is a journalism game that allows the player to become a journalist in Athens, collecting information about a riot and shows the choices that are available; it gives the players options of where to find out and source the story. La Peña uses her journalistic skills to engage “players” in the experience of being imprisoned in Guantanamo Bay, using real news sources to inform what the “player” experiences so that it is similar to what prisoners experienced. Both Achiam and La Peña argue that these type of approaches will engage and inform different audiences in finding out about the world, audiences that would not be minded to read a newspaper or watch the TV news.

There’s not yet a journalism ethics handbook that covers these approaches. Both La Peña and Achiam are award-winning journalists and have merged their existing set of research skills with a different style. Both talk about sourcing information for their news films, and La Peña offers links to evidence for her virtual-reality storytelling.

These pioneering approaches so far only have small audiences compared to TV news, but will undoubtedly challenge journalists of the future to learn new skills (video and animation look increasingly like core modules).

Interviewing, research and legal knowledge are always going to part of the mix; they are the skills that give journalists the tools to find out what others would rather they didn’t. And that skill package is always going to be vital.

Read the contents of our future of journalism special here. You can buy the print version magazine or subscribe for £32 per year here, or download the app for just £1.79.

You can also join our magazine debate at London’s Frontline Club on 22 October (free entry, but please book).

This article was published on Wednesday 1 October at indexoncensorship.org

01 Oct 14 | Magazine, Volume 43.03 Autumn 2014

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The explosion of social media, the rise of citizen reporters, the dangers of freelancing in a war zone, the invention of new technology: journalism is clearly going through its biggest changes in history. But will the public know more or less as a result?”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

This is the question we explore in great depth in the latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Contributors include Iona Craig (2014 winner of the Martha Gellhorn Prize for her reporting in Yemen); Index award nominee Dina Meza and the BBC’s Samira Ahmed. We also have an exclusive, new short story by acclaimed novelist, playwright and author Ariel Dorfman.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”59980″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

And Australia’s race commissioner, Tim Soutphommasane, speaks out on how the right to be a bigot should not override the right to be free from the effects of bigotry.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SPECIAL REPORT: THE FUTURE OF JOURNALISM” css=”.vc_custom_1483551011369{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Back to the future: Iona Craig on journalists trying to stay safe in war zones

Digital detectives: Ray Joseph on the new technology helping Africa’s journalists investigate

Re-writing the future: Five young journalists talk on their hopes and fears for the profession – from Yemen, India, South Africa, Germany and the Czech Republic

Attack on ambition: Dina Meza on a Honduran generation ground down by fear

Stripsearch cartoon: Martin Rowson envisages an investigative reporter meeting Deep Throat

Generation why: Ian Hargreaves asks on how the powerful may or may not be held to account in the future

Making waves: Helen Womack reports from Russia on the radio station standing up for free media

Switched on and off: US journalist Debora Halpern Wenger on TV’s power shift from news producers to news consumers

TV news will reinvent itself (again): Taylor Walker interviews a veteran TV reporter on the changes ahead

Right to reply: Samira Ahmed on how the BBC tackles viewers’ criticism

Readers as editors: Stephen Pritchard on how news ombundsmen create transparency

Lobby matters: Political reporter Ian Dunt on the push/pull of journalists and politicians inside Britain’s corridors of power

Funding news freedom: Glenda Nevill looks at innovative ways to pay for reporting

Print running: Will Gore on how newspapers innovate for new audiences

Paper chase: Luis Carlos Díaz on overcoming Venezuela’s newsprint shortage

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”IN FOCUS” css=”.vc_custom_1481731813613{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Free thinking? Australia’s race commissioner Tim Soutphommasane on bigotry

Guarding the guards: Jemimiah Steinfeld on China’s human rights lawyers becoming targets

Taking down the critics: Irene Caselli investigates allegations that Ecuador’s government is silencing social media users

Maid equal in Brazil: Claire Rigby on the Twitter feed giving voice to abuse of domestic workers in Brazil

Home truths in the Gulf: Georgia Lewis on how UAE maids fear speaking out on maltreatment

Text messaging: Indian school books are getting “Hinduised”, reports Siddarth Narrain from India

We have to fight for what we want: our editor, Rachael Jolley, interviews the OSCE’s Dunja Mijatovic on 20 years championing free speech

Decoding defamation: Lesley Phippen’s need-to-know guide for journalists

A hard act to follow: Tamsin Allen gives a lawyer’s take on Britain’s libel reforms

Walls divide: Jemimah Steinfeld speaks to Chinese author Xiaolu Guo about a life of censorship

Taking a pop: Steven Borowiec profiles controversial South Korean artist Lee Ha

Mapping media threats: Melody Patry and Milana Knezevic look at rising attacks on journalists in the Balkans

Holed up in Harare: Index’s contributing editor Natasha Joseph reports from southern Africa on the dangers of reporting in Zimbabwe

Burma’s “new” media face threats and attack: Burma-born author Wendy Law-Yone looks at news in the run up to the impending elections

Head to head: Sascha Feuchert and Charlotte Knobloch debate whether Mein Kampf should be published

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”CULTURE” css=”.vc_custom_1481731777861{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Political framing: Kaya Genç interviews radical Turkish artist, Kutlug Ataman

Action drama: Julia Farrington on Belarus Free Theatre and the upcoming Belarus election

Casting away: Ariel Dorfman, a new short story by the acclaimed human rights writer

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”COLUMNS” css=”.vc_custom_1481732124093{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

Index around the world: Alice Kirkland gives a news update on Index’s global projects

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”END NOTE” css=”.vc_custom_1481880278935{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-top: 15px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]

From the factory floor: Vicky Baker on listening to the world’s garment workers via new technology

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”SUBSCRIBE” css=”.vc_custom_1481736449684{margin-right: 0px !important;margin-left: 0px !important;border-bottom-width: 1px !important;padding-bottom: 15px !important;border-bottom-color: #455560 !important;border-bottom-style: solid !important;}”][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship magazine was started in 1972 and remains the only global magazine dedicated to free expression. Past contributors include Samuel Beckett, Gabriel García Marquéz, Nadine Gordimer, Arthur Miller, Salman Rushdie, Margaret Atwood, and many more.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”76572″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In print or online. Order a print edition here or take out a digital subscription via Exact Editions.

Copies are also available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Calton Books (Glasgow) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Sep 14 | Hungary

Hungarian Police © Paul Appleyard/CreativeCommons/Flickr

Photographs revealing the identity of police officers can now legally be published in Hungary.

A recent ruling of the Hungarian Constitutional Court means that news organisations can now publish unaltered photographs showing the faces of police officers without gaining prior consent

Since 2007, the Hungarian Judicial System considered the personal privacy of police officers to hold greater importance than them being published in the public interest.

Hungarian journalists regularly masked the faces of the police, or manipulated the image so that the officers could not be identified.

The Constitutional Court ruled that if the photograph is taken in a public place, shows the subject in an unbiased manner, and there is clear public interest involved in distributing the picture, then it can be published without the consent of the officer.

30 Sep 14 | Egypt, News and features, Press Releases, Religion and Culture

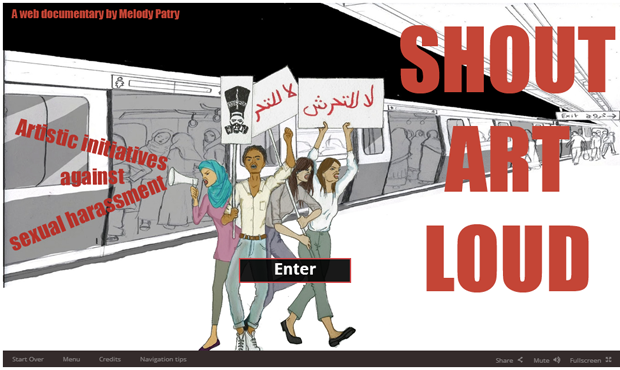

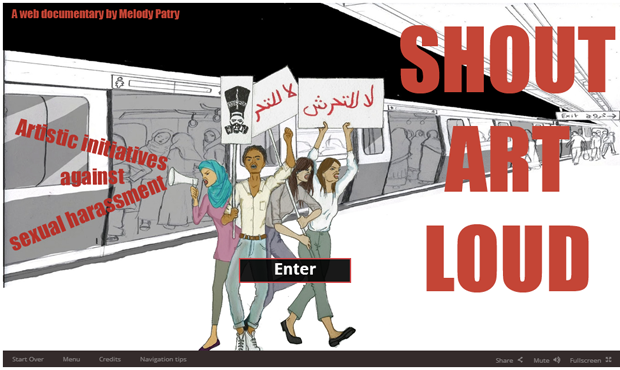

Index on Censorship’s Shout Art Loud, an interactive documentary highlighting how Egyptian graffiti artists, cartoonists, dancers and actors are fighting back against rising levels of violence and sexism on the streets of Cairo, has been named to the shortlist of the annual Amnesty International media awards.

Nominated in the Digital Innovation category, Shout Art Loud, created by Melody Patry, joins The Guardian’s The Shirt on Your Back and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism’s Covert Drone War on the short list.

Documentary maker Patry interviewed actors, dancers and other artists around Egypt, where 99% of women have experienced some form of sexual harassment, and 80% feel unsafe on the street. Sexual violence has risen sharply in Egypt in the past few years. During the period February 2011 to January 2014, Egyptian women’s rights groups documented thousands of cases of sexual harassment, as well as crimes of sexual violence against at least 500 women, including gang rapes and mob-sexual assaults with sharp objects and fingers.

With police, politicians and the judiciary seeming incapable of tackling the issue effectively, activists are turning to the arts to help lead the fight back. “Art is one of the most necessary mediums to impact society,” says Deena Mohamed who created a web-comic about a hijab-wearing superheroine who fights daily sexual harassment. “For people who are unaware of the issues women go through, I hope it helps them understand or at least give them something to think about.”

An interactive documentary intended as a “living report” that will be continuously updated, Shout Art Loud shows how Cairo residents are using different tactics to fight rising sexual harassment, including pro-women graffiti, drama workshops and street performances.

“We believe that spreading images, things that people are familiar with, women figures that people know and sayings that people know brings back some positivity about women in general,” says Merna Thomas, co-founder of a graffiti campaign to promote women’s rights in Cairo’s public spaces.

See how Egyptians are using theatre, dance, music and street art to tackle the issue of sexual harassment and violence against women in Egypt in this interactive documentary, which features interviews with artists, original artwork, videos and performances, including from Index’s 2014 Freedom of Expression Arts Award winner Mayam Mahmoud. You can access the documentary here: indexoncensorship.org/shoutartloud

“This innovative documentary is a reminder of the vital role artistic expression plays in tackling taboo subjects like sexual violence — in Egypt and beyond,” said Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “We want to bring this issue to a wider audience to show just how important artists and writers can be in bringing about change, and to tell the story in a new way.”

For further information and interview requests, please call +44 (0)207 260 2660