29 Sep 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Serbia

Serbian journalists last night gathered outside the studios of national broadcaster B92, in protest at the decision to cancel politics talk show Utisak Nedelje (Impressions of the Week).

B92 claims the popular show — on air since 1991 — has not been cancelled but postponed due to a breakdown in negotiations with its author and presenter Olja Beckovic, according to news site Balkan Insight. The channel says they had offered to continue broadcasting the show on its national frequency channel — its home since 2002 — until November, when it would be bumped to the cable channel B92 Info. But Beckovic says the show has been banned following political pressure.

“I absolutely never experienced such blackmail and pressure before,” she told website Vesti in an interview published on Friday. “And there’s something very interesting about that. People say this is a return to the 1990s. No it’s not, it’s worse than the 1990s.”

In March, the Progressive Party (SNS) convincingly won Serbia’s general election and its leader Aleksandar Vucic became the prime minister. With a chequered track record on press freedom, both as deputy prime minister in the previous government and as Slobodan Milosevic’s information minister, Index wondered at the time what impact his new role may have on Serbia’s media. Six months on, what is happening with Utisak Nedelje is just the latest addition to a worrying pattern.

It did not take long for claims of censorship to be levelled at the Vucic government. In May, Serbia and surrounding countries were hit by devastating floods. Authorities imposed a temporary state of emergency, which gave them the power to detain people for “inciting panic”. Meanwhile, online criticism of the government’s handling of the crisis was targeted. Critical articles and blogs were removed, and whole websites, including the independent news outlet Pescanik, were blocked and subjected to DDoS attacks. While it is unconfirmed who exactly was behind these incidents, they already then constituted a “worrying trend”, according to the Organisation for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE).

Index has tracked the media freedom situation in Serbia since the early days of the current government. There have been reports of a journalist being interrogated by police for sharing a Facebook post, as well as physical and verbal attacks — often with impunity. But indirect control of media, smear campaigns and other methods of covert “soft censorship” also pose a serious challenge to Serbian press freedom. “Milošević never muzzled the media this perfidiously. His methods were far less sophisticated and everything was out in the open,” said Beckovic. And it seems her colleagues agree that censorship is prevalent. Ninety per cent of journalists responding to a recent survey said censorship and self-censorship does exist in Serbian media, while 73% and 95%, respectively, said the media does not report objectively and critically.

The public dispute between authorities and the Balkan Investigative Journalism Network (Birn) is one example. The group reported that the government paid significantly more than partner Etihad Airways for a nearly equal stake in new company Air Serbia. Vucic denied the story, saying it was based on an unused draft version of the contract. Days later, pro-government newspaper Informer published an article accusing journalists from Birn and Serbia’s Centre for Investigative Journalism (Cins) of stalking and spying on Vucic. Birn has called this a “campaign to discredit” their work.

“I have the impression that the situation is getting worse,” Mehmet Koksal from the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) told Index. He cites recent reports of Serbian politicians allegedly faking academic qualifications. “In those articles you can easily measure the level of tolerance from the government to independent media owners,” he explains. He says some newspaper that pushed the story were accused in pro-government outlets of carrying out propaganda for foreign countries. “This is the kind of conspiracy theory that we used to see from different countries.” Pescanik was again brought down by DDoS attacks for reporting the story.

Recent amendments to the country’s media laws will see the state withdraw from nearly all media funding by July 2015. The move has been welcomed by many, but as think tank Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso points out, this alone will have limited impact: “Private tabloids have been for some time the main supporters of the government, and influence is exerted indirectly, mostly through the advertising market.”

Serbia has also adopted a new labour law which was heavily opposed by trade unions. Koksal claims that union leaders have faced media attacks and smear campaigns. If certain media groups or owners have an interest developing good relationships with the Serbian government, he explains, you can “easily understand why they are doing the dirty job” of attacking opposition. But finding out who exactly funds which outlet is not always easy, as bids to increase transparency of ownership has been met with resistance from private media.

After the elections, Index spoke to Lily Lynch, the founder and editor of the English-language online magazine The Balkanist, which used to be based in Belgrade. She recently decided to leave Serbia due to the pressure she has faced as an independent journalists.

“I was pessimistic about the potential for the media situation in Serbia to worsen when the new government, led by Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic, came to power in March. But I think the mask has slipped much faster than any of us expected,” she tells Index.

Lynch also believes international actors have a role to play in the worsening levels of press freedom in Serbia, explaining how the US embassy in Belgrade earlier this year told her to leave the country until after the election. “It seems the US embassy thought it was probably a better idea if I was gone because we were critical of the Vucic regime, which they supported pretty unambiguously.”

She also argues that international media bears some responsibility. “In the pre-election period, the English-language media was pretty uniform in its portrayal of Vucic as some kind of redemptive success story. There were headlines like ‘From Authoritarian Censor to EU Partner’, or ‘From Nationalist Hawk to Devout Europeanist’,” she says.

“Was it responsible for major, supposedly ‘objective’, well-respected publications to project such an image? I would say no, and it’s something I think we need to look at ourselves.”

Vucic has been widely lauded as a reformer, who has set Serbia firmly on the path to EU accession — the country’s main driver of reforms. In 2015, Serbia will also take over the chairmanship of the OSCE. During that organisation’s ongoing high-level human rights conference, the Serbian delegate said the OSCE region’s freedom of expression and media in will be high on their agenda as chairs. Many would argue they could start the work at home.

Correction 09:34, September 30: An earlier version of the article stated that Mehmet Koksal works for the International Federation of Journalists.

This article was published on Monday September 29 at indexoncensorship.org

Serbia: Protesters opposing Belgrade Pride Parade attack B92 offices

Serbia: Photographer injured by anti-pride parade protesters

Serbia: B92 TV station scrapped well-known political talk show

Serbia: Security officer interfered with journalist during political party rally

Serbia: Journalists from “Juzne vesti” labelled foreign mercenaries

26 Sep 14 | Campaigns, Statements

We the undersigned members of Artsfex condemn an alarming worldwide trend in which violent protest silences artistic expression that some groups claim is offensive. People have every right to object to art they find objectionable but no right whatsoever to have that work censored. Free expression, including work that others may find shocking or offensive, is a right that must be defended vigorously.

We call on artists, arts venues, protestors and the police to work together as a matter of urgency, to stand up for artistic free expression and to ensure that the right to protest does not override the right to free expression. This means that every possible step is taken to ensure that the art work remains open for all to see, while protesters voices are heard.

We must prevent the repetition of recent ‘successful protests’ in which the artist is silenced by threats of violence towards the institution, the work or the artist him or herself, as we saw with Exhibit B in London, and The City, the hip-hop opera by the Jerusalem-based Incubator Theatre company, which was disrupted and consequently cancelled earlier this year in Edinburgh.

Greater clarity around policing of controversial arts events is an essential first step. In the United Kingdom there is nothing at present in Association of Chief Police Officers guidance relating to the particulars of policing cultural events, except in reference to football matches and music festivals.

Controversial art triggers debate – and in the case of Exhibit B there was a huge outpouring of feeling in opposition to the work. A contemporary institution should anticipate and provide for this. Detailed planning such as this is important if the arts venue is to cater for both the artwork and the debate it generates.

We are concerned that unless arts institutions prepare procedures to manage controversy, including to develop strategies for working with the police to control violence, our culture will suffer as a result and become less dynamic, relevant and responsive.

Article 19

freeDimensional

Freemuse

Index on Censorship

National Coalition Against Censorship (US)

Vivarta

For further information, please call 0207 260 2660

About Artsfex

ARTSFEX is an international civil society network actively concerned with the right of artists to freedom of expression as well as with issues relating to human rights and freedoms. ARTSFEX aims to promote, protect and defend artistic freedom of expression, and freedom of assembly, thought, and opinion in and across all art disciplines, globally. http://artsfex.org/

26 Sep 14 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements

Before the cancellation of Exhibit B at the Barbican this week, Index published an article from associate arts producer Julia Farrington in which she addressed the role of the institution in managing controversial art and a lack of diversity in arts management in the UK. Those who read the article following the cancellation and our short comment on it have interpreted our stance as one that in some way excuses or condones the protesters and the cancellation of the piece. This was certainly not our intention, but we realise that by failing to publish a detailed article or statement on the cancellation, we muddied our position.

So let’s be clear. People have every right to object to art they find objectionable but no right whatsoever to have that work censored. Free expression, including work that others may find shocking or offensive, is a right that must be defended vigorously. As an organisation, while we condemn in no uncertain terms all those who advocate censorship, we would – as a free expression organisation – defend their right to express those views. What we do not and will never condone is the use of intimidation, force or violence to stifle the free expression of others.

As an anti-censorship organisation we think it is self-evident that no work should be censored for causing ‘offence’. But we also know that controversial art will inevitably cause controversy, including demands it be censored. Some of those who object to the work may protest. Some of those protests may turn violent. So we have also sought in much of our work on this issue not simply to condemn those who wish to censor, but also to examine what more arts organisations and institutions can do to ensure that controversial works are put on: Taking the Offensive – defending artistic freedom of expression in the UK.

We hope the debate generated by the cancellation of Exhibit B will reignite discussion on both the necessity of, and mechanisms for, staging controversial work.

This statement was posted on 26 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Sep 14 | Hungary, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Prime Minister Viktor Orbán (Pic © European People’s Party/CreativeCommons/Flickr)

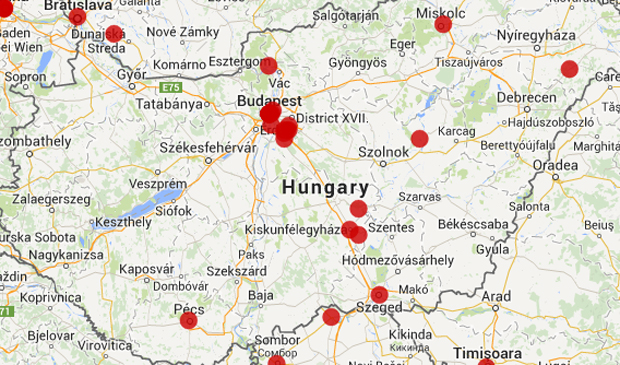

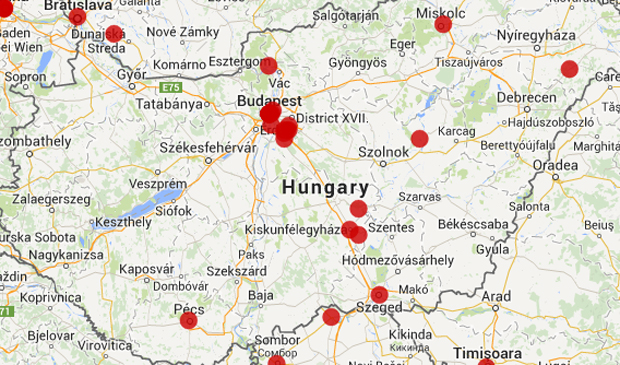

People “working together with foreign intelligence services” have been labelled “traitors” by Hungarian Deputy Prime Minister Zsolt Semjen. The comment comes after news site index.hu published a series of investigations exposing how Ukrainians and Russians are using fraudulent techniques to get Hungarian citizenship, and then travelling in Europe with Hungarian passports. The incident follows a spate of cases of government censorship and intimidation over the past year, tracked by Index on Censorship‘s media freedom mapping project.

Earlier this month, two Hungarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) who received money from the Norwegian government under a 20-year-old deal to help strengthen civil society in the poorer parts of Europe, were raided by police officers from the National Bureau of Investigation.

Ökotárs and Demnet are just two NGOs who have recently come under attack in Hungary. A government “blacklist” of the 13 “most wanted” organisations was leaked in May. The total number of groups under investigation is at 58 and growing, and includes human rights and watchdog organisations like the Roma Press Centre, Labrisz Lesbian Association and Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU).

A campaign has been launched by a group of Hungarian volunteers through the site Blacklisted Hungarians, encouraging the international community to show their support for the case on social media by using the hashtag #ListMeToo to share content and media coverage.

In addition to this, rapper László Pityinger, known as Dopeman, is at the centre of an ongoing criminal investigation, after he kicked the detached head of a statue symbolising the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. The rapper spoke at a demonstration arranged by political group Szolidaritás last October, during which the audience toppled and decapitated the statue.

He will be represented by HCLU. Dalma Dojcsák, the group’s political liberties program officer and freedom of speech expert, told Index they are trying to convince the police that Pityinger has not committed a crime.

“The police officer conducting the investigation implied that they think the same, but the prosecutors may force the case through the system until it gets to trial. We don’t know if it is going to happen,” Dojcsák said.

“In Hungary, prior, direct censorship is rare — it only happens in public service media that is ruled by the government. However, self-censorship is common among journalists, out of fear of legal procedures and losing state financed advertisement,” she added.

Deputy editor-in-chief fired from Nepszava daily

Two official bulletins appear in Kiskunfelegyhaza

28 journalists laid off by daily newspaper

Parliament speaker attempts to block interview from airing on Polish TV

Song with political reference cut from public broadcast

More reports from Hungary via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

This article was posted on 26 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Sep 14 | Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society

Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

“States must stop trying to define who is and isn’t a journalist. The media landscape has changed irreversibly,” said Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media, as she opened the organisation’s Open Journalism event in Vienna on Friday, 19 Sept.

Journalism – wherever you draw its boundaries – has more voices than ever, but are all they all being properly recognised and safeguarded? This was one of the main problems addressed by the expert panel, which included Index on Censorship, alongside delegates from Azerbaijan, Serbia, Estonia, Russia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia and many other OSCE member states.

Gill Phillips, the Guardian’s director of editorial legal services, spoke via pre-recorded video about difficulties in defining journalism and deciding who gets journalistic protection. She cited the Snowden scoop, which was led by Glenn Greenwald, a former lawyer, and later embroiled his partner, David Miranda. Who gets the protection? Greenwald? Miranda? Lead staff reporter David Leigh? All three?

There was widespread condemnation of Russia’s new law, which compels bloggers with more than 3,000 views per day to be registered with the authorities. “[The bloggers] have certain privileges and obligations,” said Irina Levova, from the Russian Association of Electronic Communications, who repeatedly defended the law. “Online and offline rights are not the same,” she said, adding that some of those who deemed the law a mode of censorship have been revealed as “foreign agents”.

Another topic – raised repeatedly by various attendees – was Russian media’s growing influence over citizens in nearby countries. Begaim Usenova of the Media Policy Institute in Kyrgyzstan said: “The common view being spread from the Russian media is that the United States is starting world war three and only Putin can stop him.”

Yaman Akdeniz, a Turkish cyber-rights activist, shared news of Twitter accounts that remain blocked in his country, including some with over 500,000 followers. Igor Loskutov, a business director from Kazakhstan, looked back on the first 20 years of internet in his country and how authorities have gone from ignoring their first rudimentary websites to now wanting complete control.

The thorny issue of “public interest” was also discussed. Jose Alberto Azeredo Lopes, professor of International Law at the Catholic University of Porto, raised some smiles with his theory: “It’s like pornography. You can’t define it. But you know it when you see it.”

As the day-long discussions wrapped up, one delegate asked: if a blogger’s first-ever post goes viral, are they immediately subject to the same laws as the press? Especially in countries that now insist bloggers register.

The debate over the difference between journalists and bloggers went round in circles – as it always does – but the OSCE is hoping to be able to compile all the findings from its expert meetings into an online resource to move the discussion forward.

Azeredo Lopes concluded: “If you don’t distinguish freedom of expression from freedom of the press, you end up with no journalists, and that is the crisis that journalism faces today.”

Read our interview with Dunja Mijatovic, OSCE’s Representative on Freedom of the Media, in the autumn issue of Index on Censorship Magazine, coming soon

This article was published on Friday September 26 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Sep 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Uncategorized

Rasul Jafarov in September 2013 (Photo: Melody Patry)

This is the appeal of Azerbaijani political prisoner, Rasul Jafarov. It was sent to Index on Censorship by his brother, Sanan Jafarov. Jafarov has now been detained for 54 days.

Article 157 of the Code of Criminal Procedure deals with the restrictive measure of arrest. Article 157.2 states that arrest as a restrictive measure may be chosen in the light of the requirements of Articles 155.1 – 155.3 of this Code. In other words, a restrictive measure, including the restrictive measure of arrest may be chosen when the grounds stipulated in the Articles 155.1 – 155.3 exist. These grounds are the following, and I present my arguments regarding the baselessness of the attribution of each ground to me and the fact that there was a ‘political order’:

- 1.1 – hiding from the prosecuting authority;

In connection with my activities as a human rights defender, I have regularly been in the spotlight of the local community and the media. At least once a week, I gave interviews to local media outlets in their offices. The interviews were explicitly related to the human rights situation in Azerbaijan. To talk about these issues one needs to constantly live in Azerbaijan. And I have always lived in Azerbaijan. Despite of making numerous trips in connection with my work, I always returned to the Homeland. This was the case on the eve of my arrest. I came back to Baku in late June after participating in the summer session of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. From 29 June to 5 July I was on a visit to Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and from 6 to 11 of July on a visit to Kiev. The last visit is particularly important, because on July 7, while I was in Kiev, the Sabail District Court issued a decision to arrest my current bank accounts based on the request of the investigating authority, i.e. while stil in Kiev I already knew that the Prosecutor General’s Office conducts an investigation related to me. Nevertheless, I did not choose to hide from the investigating authority and returned to Baku on July 11. On July 16, I submitted a formal application to the Sabail District Court requesting a copy of the decision to arrest my bank accounts, in order to appeal that decision. On July 28, I left Baku for Tbilisi by train for a next working trip; in the morning of July 29, I was told at the Boyuk Kesik border crossing point that the Prosecutor General’s Office imposed a ban on my exit from the country on July 25. This ban is, as a rule, imposed on suspects and accused persons. However till then I had not been prosecuted as a suspect or accused. Yet, I not only did not think about hiding, but immediately returned to Baku after being taken off the train and informed the local media about this ban. After this information was disseminated in numerous media outlets, a member of the investigation team, an investigator by name Igbal Huseynov called me on July 30 and invited me as a witness to the Depatment for Investigation of Serious Crimes of the Prosecutor General’s Office on July 31, at 9.30. I did not hide from the investigation and was in the investigating authority at the specified time in order to answer the questions of the investigation. There, I gave evidence for 4 fours in the presence of two investigators, and answered all the questions that interested the investigating authority. After the questioning, a search was conducted in the apartment where I live for 2 hours with my own participation (the search order was made on July 25). Since the investigating authority found nothing as a result of the search, I told that I can voluntarily present the documents that the investigating authority needed. Thus, on July 31, August 1 and on the day of my arrest, i.e. August 2, voluntarily presented the financial and accounting documents of the human rights projects that we carried out during the period 2011-2014. On August 2, after presenting the last documents on the projects I was charged as the accused. Because I cooperated with the investigation, regularly complied with the summons of the investigating authorities and, above all, presented all the documents requested for normal conduction of the investigation, there remained no logical or any other point in my hiding from the investigation from that moment on. On the other hand, due to the ban imposed on my exit from the country, I could not hide from the investigation by leaving the country, even if I wanted.

- 1.2- obstructing the normal course of the investigation or court proceedings by illegally influencing parties to the criminal proceedings, hiding material significant to the prosecution or engaging in falsification;

Firstly, I should note that the scope of the persons involved in the criminal proceedings is unclear to me. The current criminal case was launced on 22 April 2014 and covers the activity of more than 20 NGOs and NGO representatives. In such a case, it is difficult to even imagine the possibility of how and which parties to the criminal proceedings were influenced during nearly 4 month until my arrest. If we answer the question “who were these people?” with assumptions, we can suppose these people to be the persons who rendered different services under the projects that we carried out. The projects that we carried out, the people involved in them, the documents that emerged as a result of projects and the outcomes have regularly been in the spotlight of local and a number of foreign media, and discussions have been opened around them. On the other hand, the identity of the persons involved in the projects, the jobs that they were engaged in and the amounts of funds they received in return for their work are indicated in the financial and accounting documents that I voluntarily presented to the investigating authority. I should underline that I present not the copies but the original documents to the investigating authority and relevant acts were drawn up. In such a case, there remains no point in inluencing the people involved in projects for any reason, because all original documents related to them have already been presented to the ivnestigating authority. This fact also proves the fact that it is impossible to falsify any document or material. Since on 3 consecutive days I voluntarily presented the documents requested by the investigation, the concealment of any document is out of the question, as we have no document to hide. The projects that we carried out were obvious, I gave additional information about each of the projects during my testimony on July 31, the investigating authority possesses bank statements about my bank accounts, I have presented all financial and accounting documents on the projects, thus I let the investigation know the exact scope of persons involved in the projects. This being the case, the hiding or falsying of which documents can one talk about? Or is there a need to influence the people, when their involvement in the projects is proved by their own signatures and the investigating authority already has these documents?

- 1.3 – committing a further act provided for in criminal law or creating a public threat.

The nature of the crimes with which I am charged is so that it is impossible to commit them again in the course of the current criminal proceedings; Because the projects have been stopped due to the criminal case, all my current bank accounts have been arrested by a court decision, the documents of all the previously implemented projects are in the possession of the investigating authority. This being the case, how can I re-commit the crimes with which I am charged? The crimes with which I am charged are not homicide, causing grievous bodily harm, hooliganism, drug possession, drug trafficking, rape or crimes resulting in serious consequences of these kinds, there do not exist grounds for prevention of their re-commital or a public threat.

- 1.4 failing to comply with a summons from the prosecuting authority, without good reason, or otherwise evading criminal responsibility or punishment;

As I noted above, the first time I was summoned by the investigation on July 30, and on July 31, at 9.30, I was at the investigating authority, I also complied with the August 1 and August 2 summons of the investigating authority in a timely manner, without any delay. As we can see, I not only did not avoid the summons of the investigating authority, to the contrary, I have consistently complied with them. After my July 31 evidence, the search in my apartment and the presentation of the documents to the investigation, I gave information about what had happened on my Facebook page, stating that my activity was transparent, that I had not committed any crime and that I would prove this to the investigation. I repeated my similar interviews in the interviews that I gave to the local media both on the same day and August 1.

- 1.5 preventing execution of a court judgment;

How might I have prevented the execution of a court judgment, when there exists no court judgment on this case or in relation to me. It has been set out in Article 155.2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure that in resolving the question of the necessity for a restrictive measure and which of them to apply to the specific suspect or accused, the preliminary investigator, investigator, prosecutor in charge of the procedural aspects of the investigation or court shall bear in mind:

155.2.1. the seriousness and nature of the offence with which the suspect or accused is charged and the conditions in which it was committed;

– Only one of the crimes with which I am charged, abuse of office, is considered a serious crime by its category, the other 2 crimes belong to the category of less serious crimes. In other words, if we summarize the crimes, among them, I am accused of committing only 2 less serious and 1 serious crimes. These charges filed against me cover my human rights activity that I have implemented for 3 years, i.e. I have established the non-governmental organization not to commit these crimes, but to implement human rights activity. And, I obtained the TIN (taxpayer identification number) in 2008 not to avoid payment of taxes or engage in illegal business activity, but to be registered as a taxpayer and pay the taxes. In other words, even if we suppose that the crimes have been committed, there are no proofs to claim the gravity of the circumstances of their committal, or to show that there was a specific intent or planning, or criminal intention in the action. As a result of the action that has been allegedly committed, no one has lost their life or suffered serious injuries, there has not been an obvious disrespect for a society, no one’s Constitutional rights or freedoms have been violated, and there is no concrete victim or complainant. The article of the Criminal Code that concerns tax evasion, one of the charges brought against me, itself provides for the exemption from criminal responsibility.

155.2.2 the personality, age, health and occupation of the suspect or accused and his family, financial and social positions, including whether he has dependents and a permanent residence;

– I have worked in civil society organizations since 2007, and have been author, implementer or participant of a number of projects that were useful for the society. I graduated from the university with good and excellent mars and got a master’s degree in law. In 2006-2007 I served in the army and was discharged with the rank of junior sergeant. I am considered the head of my family since 2004, as my father died in October of that year, and since then I play a key role in maintaining our family that consists of me, my mother and younger brother. I have a resident which is my property and the investigation knows this, there is no other address where I actually live, I do not have a citizenship of any other country or have no obligation to a foreign state. In 2010, I was the winner of the Asian Justice Makers Competition of the International Bridges to Justice organization, in 2013 I was a participant of the prestigious joint program of the American Jewish Committee and Fridrich Naumann Foundation called “Promoting Tolerance”, I closely participated in numerous meetings of the Council of Europe, the UN, the European Union, OSCE and other international organizations, and made speeches on the theme of human right at a number of events.

155.2.3 whether he has committed a previous offence, the previous choice of restrictive measure and other significant facts;

I have never been convicted before, no restrictive measure has ever chosen in respect of me, I have never been recognized as a suspect or accused in committal of a crime, even no administraive measure has ever been applied to me, and my name has not been mentioned in any criminal case. I complied with the summons of the investigating authority in a timely manner and cooperated with the investigation.

Conclusion

There was no ground to refuse choosing the measure of house arrested in respect of me as an alternative to the resitrictive measure of arrest. Along with the house arrest, the court could completely ban me from leaving my place of residence as an accompanying measure and additional restrictive measures stipulated in Article 163 of the Code of Criminal Procedure could be applied. We have presented reliable evidence proving this to all local courts. When our evidence are taken into account not seperately but as a whole, it becimes clear that there is no serious ground or necessity to apply restrictive measure of arrest to me. Thus, instead of arrest, the measure of house arrest, which is its alternative according to the legislation, could have been easily chosen in respect of me.

This article was posted on 25 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Sep 14 | News and features, Religion and Culture, United States

(Photo: Shutterstock)

For us jaded Europeans, the United States’ first amendment, with its simple pledge that the government will keep out of the business of religion and censorship, seems as stubbornly, oafishly American as Hulk Hogan. It’s a loud tourist with a bumbag, wasting his money in an Angus Steakhouse; it’s Burt Reynolds’ moustache; it’s Jane Russell’s specially-constructed brassiere; it’s brash and unsubtle and does not do nuance.

Which is why we’re so ready to accept the idea that a US court has decided that the first amendment concept of free speech trumps all, even sexual harassment. Especially if that court is in Texas, the bit, we imagine, that makes the rest of the United States look sophisticated.

“Texas court upholds right to take ‘upskirt’ pictures”, said the Guardian, while the Independent tweeted “You’re legally allowed to take upskirt pictures in Texas because it’s ‘freedom of expression’” (note the scare quotes).

The stories under the headlines concerned a ruling by the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in a case concerning a man named Ronald Thompson.

Thompson had been caught taking pictures of children and women at a water park in San Antonio, focusing on what I believe is called the “bikini area”. Thompson reportedly tried to delete the photos as he was apprehended. He was indicted on 26 counts under Texas’ “improper photography or visual recording” law.

Thompson appealed the indictments on the grounds that the law was incompatible with the first amendment. The court agreed with him, leading to the headlines across the world. Most reports, including, it should be said, the American ones, went hard on the “upskirt” or “creepshot” angle, declaring it was now entirely legal to well, be a creep with a camera in Texas.

Is it really? Well, sort of, ish.

The judgement issued by the court is a genuinely fascinating read for anyone interested in free expression, far from the gun-toting, sexual harassment-ignoring, good ole boy decision it has been represented as. It involves discussion about what constitutes the public realm and the nature of consent. It goes into some detail as to whether the act of photography is in itself creative expression, and decides it is.

Some commentators, such as Salon’s Jenny Kutner have picked up on the wording in the judgment suggesting that “Protecting someone who appears in public from being the object of sexual thoughts seems to be the sort of ‘paternalistic interest in regulating the defendant’s mind’” as evidence of a court being more interested in a pervert’s right to perv than a woman’s right not to be harassed.

But it’s actually a point well worth making. Courts and governments cannot be involved in what people find sexually arousing in their imaginations; it’s only if actions cause harm to others that the law should intervene.

This is not, then, a ruling taken lightly. Rather it reviews very seriously a badly written law.

The law itself, section 21.15 of the Texas Penal Code, reads as follows:

(b) A person commits an offense if the person:

(1) photographs or by videotape or other electronic means records, broadcasts, or transmits a visual image of another at a location that is not a bathroom or private dressing room:

(A) without the other person’s consent; and

(B) with intent to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person;

The “bathroom or private dressing room” exclusion seems weird, but is only there because the next clause specifically refers to bathrooms and private dressing rooms, presumably drafted in light of some kind of Chuck Berry scenario (the guitar legend was accused of secretly taping people using bathrooms in his Missouri restaurant).

The problem is that this is far too broadly drawn as a law, but also weirdly specific. What it does not address at all is what might be a reasonable expectation of privacy in public: it is not a serious argument to suggest that one must always actively give consent to being photographed in public space. But it is reasonable to expect that no one should be taking upskirt pictures of you: the judgment acknowledges as much, specifically mentioning upskirt photographs as an “intolerable” breach of privacy.

The weird specificity comes with the “sexual desire” bit; why is this kind of thought worse than any other? Shouldn’t the focus be on the breach (or not) of privacy, rather than what thoughts the images might lead to? Apart from the argument over whether photography is an act of expression, it is this clause that raises free expression problem with the law: put simply, the human mind is capable of eroticising pretty much anything. Any kind of picture could “arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person”. Once again, the focus is in fact taken away from the act of breaching privacy and towards the act of expression.

In spite of initial appearances, the Texans have done a good thing here. The state will now have to come up with a law that properly balances privacy and free expression, rather than giving just piecemeal thought to either concept.

First amendment cases often solicit astonished responses. But more often than not, a first amendment consideration isn’t just free expression rolling into town in its monstrous, burger chewing, gasoline drinking, Okie from Muskogee way. No. More often than not, the first amendment forces some real thought and analysis to take place in public life.

This article was posted on Thursday, September 25, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Sep 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

Rasul Jafarov, Arif Yunus and Leyla Yunus (Photos: Rasul Jafarov (© IRFS), Arif and Leyla Yunus (© HRHN))

Disregarding the motion by European Parliament earlier this week, Azerbaijan has failed to release political prisoners Leyla and Arif Yunus, Rasul Jafarov, Intigam Aliyev and Hasan Huseynli.

Leyla and her husband have now been imprisoned for 56 days, since July 30. On September 22, Leyla’s lawyers questioned her current condition after not being allowed into her cell and being denied an opportunity to speak with her on the phone. Guards told the lawyers she was sick and refused to speak with them. In a joint statement the lawyers expressed that the circumstances Leyla is being exposed to in the prison, including being subjected to acts of violence, “raise a lot of concerns”.

Jafarov, now detained for 53 days, since August 2, wrote an appeal earlier this week in which he asserted that he was falsely accused of hiding evidence and not cooperating in the investigation, and that his imprisonment is a result of a government order. “I present my arguments regarding the baselessness of the attribution of each ground to me and the fact that there was a ‘political order,’”he wrote.

Intigam Aliyev has been imprisoned for 47 days, since August 8. Hasan Huseynli, who has been detained for 178 days, since March 30, was recently sentenced to six years in Azerbaijani prison.

These five and 93 other political prisoners held in Azerbaijan were the subject of last week’s Platform London protest outside of BP’s headquarters on September 17. The protest called for BP to end its funding of the authoritarian regime on the anniversary of “the Contract of the Century”. A letter was also given BP, requesting they call on the Aliyev regime to release the 98 political prisoners and that they end their sponsorship of the 2015 Baku European Olympic Games. BP verbally agreed to meet with Platform, but has yet to formally respond to the letter.

This article was posted on 25 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 14 | News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Exhibit B will take place at the Barbican Sept 23-27, 2014. (Photo: © Sofie Knijff / Barbican)

Update: Exhibit B was cancelled by the Barbican, the Evening Standard reported, after protesters blockaded the entrance and branded it ‘racist’.

If artistic culture is to be truly dynamic, strong, representative and relevant, the programmes in our theatres, galleries and museums will necessarily be challenging. The work, presented by many different voices, will likely be divisive; and causing offence, whether unintended or deliberate, is unavoidable.

The role of the arts institution in this dynamic cultural life is to manage the space between the artist and the audience, to create a place in which different ideas about the world we live in can be expressed, challenged, exalted, ridiculed and celebrated.

Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B, programmed for four days at the Barbican beginning tomorrow, has certainly caused considerable offence; 22,500 people have signed a petition calling for the Barbican to withdraw this exhibition, declaring their intention to protest outside the venue during the run.

The work by the South African theatre maker was inspired by human zoos, popular in 18th and 19th centuries, where human beings of African heritage were put in cages on display alongside animals for the titillation of European audiences. It recreates 12 tableaux of atrocities featuring live actors, who the audience is asked to observe in silence. Brett Bailey’s idea behind Exhibit B is to immerse the visitor in visions of horror and inhumanity to “provoke audiences to reflect on the historical roots of today’s prejudices and policies”.

What interests me here is the role and mindset of the institution presenting this piece of work and whether it considered, if at all, the possibility of a hostile response. I requested an interview with the Barbican, but was told they would speak after the show, once I had seen the exhibition.

For Exhibit B to be anything other than another here-today-gone-tomorrow exhibition that takes the messages of the work to heart, the Barbican would have to be engaged in dialogue with black artists and audiences as part of an ongoing commitment to eradicate institutional racism from the arts. Yet it is the boycott organised against this exhibition, with its petition, speeches, protests, marches, public meetings, pickets, on and offline debate that is ensuring that any dialogue is happening, albeit in reaction to the programming of Exhibit B, and from the outside.

In response to the boycott, Barbican commissioned Nitro to organise a public debate: Discussions, Learning and Legacy at Theatre Royal Stratford East Monday 22nd.

The panel for the passionate and heated debate about Exhibit B, excellently chaired by Olu Alake, featured six speakers – three supporting the boycott, including Sara Myers author of the Petition and three supporting the work including Louise Jeffries from the Barbican who programmed the work. After each speaker had had their say, the audience of around 150 people, unleashed a barrage of questions from the floor. The two hours allotted to the debate were woefully inadequate for the range and depth of opinion expressed. As anticipated the debate changed nothing in the short term, the work will open this evening as planned, but there was an urgent call for a longer, fuller discussion which hopefully Barbican will respond to as a matter of urgency.

By giving a major international platform to Exhibit B without significant contemporary context, engagement or dialogue, the Barbican is unwittingly shining a light on both its own failure and the failure of the wider arts and culture scene to challenge prejudice and policy in the arts in the United Kingdom. Surely it cannot be possible for the Barbican to stand by a work that purports to confront “colonial atrocities committed in Africa, European notions of racial supremacy and the plight of immigrants today” and not see that it is holding up a mirror to itself.

Mark Sealy, artistic director at Autograph Black Photographers, who I spoke to last week about the boycott, was unequivocal: “Since 1980s it is progress zero. Our institutions have failed to bring about change – whether it is academia, the McPhearson Report or funding policies – [black] people feel absented from power, authoring and having a voice” And the reason? “There are no consequences to this failure. These policies have not made an iota of difference. If they want their institutions to be truly diverse they would withdraw the money from institutions if they don’t deliver.”

Independent arts consultant Jenny Williams takes a pragmatic view by heading up the campaign JustCulture, featuring a 10-point manifesto for change, though she knows, also from years of experience, without investment and commitment from the establishment there is little hope that things will change. She has crunched the numbers: “The Arts Council funding of arts infrastructure is not fairly representing the 14% black and minority communities. 14% of ACE’s overall three-year investment of £2.4bn would equate to £336m – that’s £112m per year. The black and minority ethnic community contribute around £62m per year into the overall arts budget. Yet, the current yearly figure currently invested in black and minority ethnic-led work is £4.8m.”

In spite of this grossly unbalanced situation, the organisers of the boycott I have spoken to are talking about how they can turn this into a positive. As Sara Myers, author of the boycott told me, she sees the mass outpouring of frustration and outrage as a catalyst. “A door has opened and we want to take the opportunity to challenge stereotypes, rather than sit back and see them reinforced.” She was however shocked when she met the board and senior management of the Barbican – with one exception, all white.

In her five-star review of Exhibit B for The Guardian, Lyn Gardner says the show “reminds us that most history is hidden from view”. I would say history here is on display for all to see. I defend Brett Bailey’s right to present these horrendous atrocities from the past – anything else is censorship – and agree with Lemn Sissay that we should all be free to revisit this story “in every part of every generation”.

But the more potent issue here, is the perpetuation of institutionalised mono-cultural bias preventing the Barbican, and the vast majority of British arts institutions, from fostering and delivering a truly relevant cultural programme. This untenable form of censorship must be addressed and continue to be addressed long after Exhibit B has been and gone.

This article was posted on 22 September 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 14 | Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey

Former Turkish Prime Minister and current president Recep Tayyip Erdogan spoke to tens of thousands of supporters during a presidential campaign rally in Istanbul in early August. (Avni Kantan / Demotix)

Seven months after a previous amendment was introduced to Turkey’s contentious 5651 law governing internet activity, new restrictions were passed late on September 8. Before the February amendments were signed into law by then President Abdullah Gül, a protracted approval process over the course of a few weeks helped bring attention to the proposals. In contrast to the online and street protests against internet censorship that preceded the amendments’ approval earlier this year, last week’s changes to the 5651 law were rushed through a vote before word could spread about them.

The newest restrictions are only two articles tucked into a lengthy omnibus reform bill: in a total of seven sentences, amendments number 126 and 127—part of a list of 146—succinctly make way for invasive data logging and the speedier blocking of access to websites. Nihan Güneli, an Istanbul-based technology and media lawyer, said the hurried vote on the bill kept opposition to the internet regulations muffled. When the details of the earlier 5651 amendments were first presented in January, Güneli said, “everybody was protesting it. I believe that was one of the main reasons Abdullah Gül rejected these two main articles. But this time we didn’t have any time. We just saw the article and everybody was shocked.”

Before approving the last amendments in February, Gül urged legislators to adjust two of its articles: one measure allowing for Turkey’s Telecommunications Directorate (TİB) to block access to some websites within four hours – without a court order, was changed to require judicial review. Another measure that gave TİB the right to collect internet users’ data was changed to restrict access to user logs.

Former Prime Minister Erdogan replaced Gül as Turkey’s new president on August 28. Less than two weeks after his inauguration, these newest internet restrictions allow for websites to be blocked within four hours if their content is ruled a threat to national security or public order, or if restricting access to them can prevent a crime. Under the new amendment, TİB is also allowed to store internet users’ traffic logs and metadata. In an attempt to make the February bill amendable to critics, these two most offensive parts of the previous amendments to 5651 were dropped at Gül’s request. Now exactly those measures have been quietly put into effect under Turkey’s new president.

The targeting of websites determined to be threats to national security comes after the Turkish government struggled to suppress a series of leaked phone recordings earlier this year that spread on social media. The wiretapped phone conversations featured what appeared to be the voices of Prime Minister Erdogan and people close to him, and pointed to their implication in an ongoing corruption scandal. Other recordings ostensibly showed Erdogan’s meddling in the judiciary and with owners of major media outlets. In March, a leaked recording from a meeting at Turkey’s foreign ministry detailed the government’s considerations for military involvement in Syria. Shortly after that recording was posted on YouTube, access to the platform was blocked entirely in Turkey.

YouTube is one prominent example of access restrictions prior to the most recent legislation reform—the website was previously banned for over two years up until 2010. The possible effects of the newest amendments’ measures for blocking websites are still unclear, although the implications for access to information are startling. A number of small, alternative news websites have been aggressively covering the Turkish government’s recent corruption scandal. With no offline distribution form, their livelihood would be put at risk if their websites became inaccessible.

The news website Diken was founded in January 2014 and has since gained a following for its alternative reporting. In June, Diken was named “internet newspaper of the year” by an environmental organisation. Editor in chief Erdal Güven says Diken published almost every one of the leaked government phone recordings earlier this year. So far, Diken has not been shut down or admonished by authorities, which Güven suggests may be because the website is still less than one year old and may not be considered a sufficient threat. Diken risks being targeted by TİB at any point, though, says Güven. “It depends on an advisor to a minister, an MP, the president. Just to read a story of ours and then complain to the legal authorities,” Güven said. Referring to the fines media companies can face for publishing information deemed illegal, Güven added, “They can ask us to pay a huge amount of money. We don’t know what they will do. We don’t have a huge amount of money, we have a tight budget. Of course this would affect us.”

Because of their editorial choices and coverage of government scandals, alternative news sources and social media are the main targets of the new restrictions on website access. Elif Örnek, a reporter for the leftist newspaper soL, says that journalists are often pressured or face censorship, and in reporting on issues that the government is trying to suppress, like the leaked phone recordings, the stakes can be especially high for the media. “The main thing is that when you’re thinking about the public interest, there are some dangers you have to risk,” Örnek said.

For internet users, TİB’s broad collection of metadata is a newly legal tool for monitoring online activity. Nihan Güneli says it’s impossible to predict how TİB will purpose users’ traffic logs. “Within six months, maybe we’ll hear about a case, maybe somebody will be arrested or someone committed a crime and we’ll see this traffic information in court. Then we’ll know what they’re doing with it,” Güneli said. Censorship of websites within Turkey is not new, making it hard to predict whether the new bill’s other article, which gives TİB the authority to block sites within four hours, will have palpable effects on access to information. “TİB has power right now and nobody knows what they’re going to do with it. I don’t think they know either,” Güneli said.

Media violation reports from Turkey via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Twitter account of Today’s Zaman editor faces closure

Habertürk fires reporter

Journalist kidnapped and released by PKK

Report shows media use of hate speech increased in early 2014

Several media organisations denied accreditation to AK Party congress

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 14 | News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

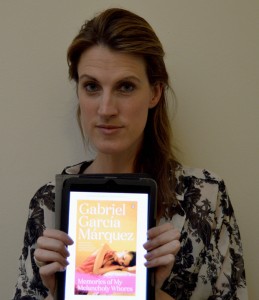

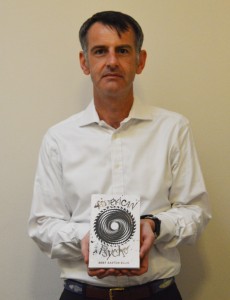

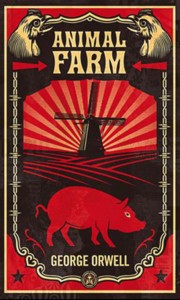

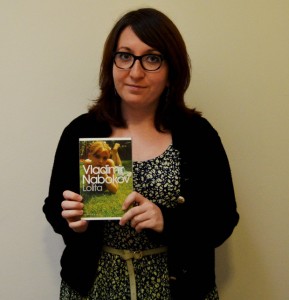

Monday was the beginning of Banned Books Week, the annual celebration of the freedom to read and have access to information. Since the launch of Banned Books Week in 1982, over 11,300 books have been challenged, according to the American Library Association. To mark the occasion, Index on Censorship staff posed with their favourite banned books, and tell why it’s important that they are freely accessible.

David Sewell (Photo by Dave Coscia)

David Sewell – Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

“Banned by the Soviet Union for being decadent and despairing and although they’re right in their analysis, the action to ban the book clearly is ludicrous. It’s a Freudian tale of Gregor Samsa who awakes one morning to find he has turned into a human sized bug and how his family react to this turn of events and treat him with revulsion and yes despair, since their main breadwinner is now out of commission. For a book about an insect grubbing about in filth, Kafka’s writing evinces some great beauty as did all his work despite the seam of despair underpinning many of them. Maybe this beauty through despair is what the Soviets meant by ‘decadent’. Kafka was a vital link between the end of the Victorian novel and the literary modernists and the influence of Freud’s ideas increasingly being used in characterisation. That is why ‘Metamorphosis’ is a significant book in the literary canon.”

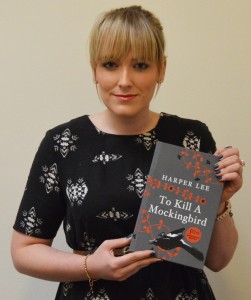

Aimée Hamilton (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Aimée Hamilton – To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

“Because of its use of profanities, racial slurs and graphically described scenes surrounding sensitive issues like rape, Harper Lee’s award winning novel has been banned in many libraries and schools in the United States over its 54 year history. Having read this beautifully written book at school, I think it should be a freely accessible curriculum staple, to be both enjoyed and admired by all.”

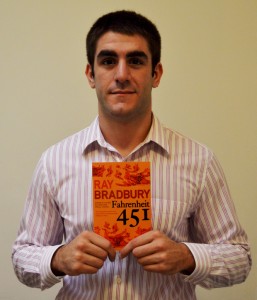

Dave Coscia (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

David Coscia – Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

“Failing to or not choosing to see the irony, many schools in the United States banned Fahrenheit 451 based on its offensive language and graphic content. Bradbury’s grim view of a future where firemen are not people who put out fires, but instead set them in an attempt to burn books outlawed by the government, acts as a warning against state sponsored censorship, even if it’s not what he intended. Bradbury himself talks about Fahrenheit as a warning that technology would replace literature and cause humanity to become a “quick reading people.” What resonates with me about the novel is how prophetic that turned out to be. In the age of social media and instant information, humans, myself included, have gotten lazy and spend less time enjoying literature.”

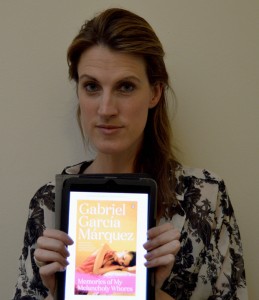

Vicky Baker (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Vicky Baker – Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel García Márquez:

“I picked this after reading how it was banned in Iran in 2007. Initially, it slipped through the censors’ net, as the Persian title had been changed to Memories of My Melancholy Sweethearts. It was on its way to becoming a bestseller before the ‘mistake’ was realised and it was whipped from shelves, accused of promoting prostitution. It’s classic tale of censors judging a book by its title.”

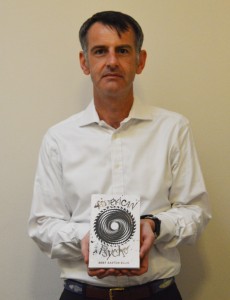

Sean Gallagher (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Sean Gallagher – American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

“No book, no matter how vilified or disliked, should be out of reach for anyone who wants to read it.”

Jodie Ginsberg (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Jodie Ginsberg – Forever by Judy Blume

“I was one of the first girls in my class to own Judy Blume’s Forever and it was passed clandestinely from classmate to classmate until it finally fell apart, dog-eared (and highlighted in certain places…). It is a book that is powerfully linked in my mind – as for so many young kids – to the transition from childhood into the tricky years of teenage life. Reading it felt shocking, even dangerous. But also liberating.”

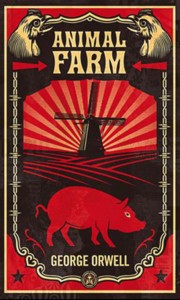

David Heinemann’s choice – Animal Farm

David Heinemann – Animal Farm by George Orwell

“It seems to have upset people from all ends of the political spectrum in one way or another at different times but what I love is that the story is actually quite ambiguous if you read it carefully, tearing pieces out of everyone and all angles. For its extraordinary imaginative power, the sheer audacity of its metaphors and it’s sharp alertness to the truths of life I treasure this book, having read it and been reminded of it so many times. I even adapted and staged the thing once, banning it is like depriving life of liquor.”

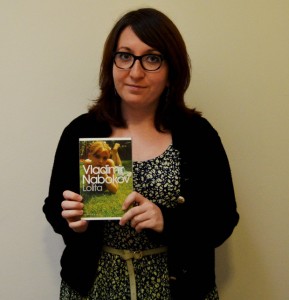

Fiona Bradley (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Fiona Bradley – Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

“I have chosen Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov because I think it is so deeply disturbing that it deserves to be read. It manages to convey some of the darkest human desires and emotions and these are exactly the kind of things that literature and art should explore. By banning it you are not protecting people but patronising them by refusing their right to judge it for themselves.”

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Sep 14 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, News and features

Marilena Katsimi, journalist and general secretary of Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers (ESIEA)

Freedom of information and media’s role as a “watchdog” has deteriorated in Greece over the past six to seven years, as a result of the economic crisis and the fiscal agreements signed by the Greek government.

Marilena Katsimi, journalist and general secretary of Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers (ESIEA) — the largest journalist union in the country — was targeted in October 2012 for commenting on air about the response by Nikos Dendias, ex minister of public order, to an article published in the Guardian. The article mentioned allegations of police brutality against protesters.

Katsimi with her colleague Kostas Arvanitis were suspended for voicing mild criticism, sparking reactions in the journalistic community and on social media.

Index on Censorship spoke with Katsimi about how censorship is exercised in Greece, and to what extent journalists are allowed to report on social struggles in the country.

Index: How would you describe the media censorship in Greece in recent years?

Katsimi: Listen, I want to be clear. There was always censorship in most of mainstream media in Greece (TV, newspapers, radio). It appeared mainly with the form of self-censorship; we all knew for whom we were working for and what we were “supposed” to say or to report.

However, as a reporter for the international news desk of ERT (Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation), the ex state-owned broadcaster, I have experienced a high degree of freedom in reporting. I can’t recall any incident of being targeted at my time there, even when I took a firm stand on certain news reports.

When we were working for the morning news magazine, together with my colleague Kostas Arvanitis, I tried to be fair and balanced according to the journalistic principles a public broadcaster should adhere to: objectivity, plurality etc. In this context, I managed to speak my personal opinion several times without being censored.

However, since the fiscal agreements between the Greek government and the troika and the austerity measures that followed up, we clearly saw that much was about to change.

Initially, the duration of the broadcast was cut by two hours with no convincing explanation. Later on, we were suspended because we commented on the response of Nikos Dendias, ex minister of Public Order, to an article published in the British newspaper The Guardian.

And then came the closure of ERT. In my opinion, it was a move by a suppressive regime that wanted to manipulate public opinion and exclude any opposition voice.

Index: Could you give us some other examples of censorship?

Katsimi: As a general secretary of ESIEA, Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers, I am responsible for the new members that join the Union.

While discussing censorship issues with the 70 new members about to register in ESIEA, I was informed that “censorship pressure was unbearable”. Editors-in-chief, media executives and other managerial staff told journalists in an overt way that “this is the proper way” of reporting while expecting from them “a certain political twist” in stories.

Let me give you another example, the one of privately-owned ANT1 TV. On the eve of the Euro elections in May, the main news bulletin of the station reported unsubstantiated information on opposition party SYRIZA’s alleged internal disagreements about getting out the vote from Golden Dawn (neo-nazi party) sympathisers! At the same time, the bulletin overemphasised that a possible outcome in favour of SYRIZA would destabilise the country and it would be a serious political accident.

After some contacts I made with journalists from privately owned ANT1 TV, I was told that there was a straightforward message on how to “report” the news and “shape” these stories. However, there has not been a single official complaint because many fear of losing their job.

For years, in privately owned media, journalists struggled to express their own voice and criticism through their reports — but now things have gotten much worse.

Index: Can you say something about the conditions in the newspaper sector? It seems that censorship comes always with a great loss of jobs.

Katsimi: Yes, this is true, up to a certain point. From 2005 until 2012 the newspapers’ sales numbers declined by 50% — consequently, there was a great loss of jobs. According to data regarding ESIEA members, the number of unemployed journalists from 2009-2014 is 749 while from 2003-2008 the same number was 69.

Let me say that as a union we do our best so that nobody stays unemployed, however, we have to face this grim reality in the media sector. In consultation with journalists’ assemblies and their representatives we try to push employers to pay on time and pay back compensation that they owe to media workers.

Because of the economic stalemate, there is a huge difficulty for most of the media to take loans from banks and continue to be viable. This in turn, functions as an excuse for media owners to put all sorts of pressure on journalists. They are often being threatened with layoffs in case they refuse a salary reduction; and bear in mind that those still with a job have already seen their salary vanish.

At the moment 400 journalists — members of ESIEA have already contacted our legal department to exercise their right of labor lien. All these cases refer to the three years between 2011-2014.

Index: Let’s get back to content issues. How would you describe media reporting on the major social and political problems in the two years before the EU parliamentary elections in May?

Katsimi: I think that news criteria in Greece vary according to the interests of the particular media outlet. For years, there were hardly any “quality” papers which tried to criticise government policies in an honest and healthy manner. At the same time there were plenty of “tabloids” which reported on the basis of populism and sentimentalism.

However, in my opinion, mainstream media and especially those that supported government policies without doubts or second thoughts, are the ones that did not give space to the social struggles in the form of strikes, anti-fascist rallies, demonstrations and confrontations with the police.

When it came to major news stories like the mining conflict in Skouries, Northern Greece, most of the media failed to report the amount of dissent and the size of the demonstrations that took place in that area and in other big cities. The story of Skouries was by all means a “scoop” of citizen, grass-roots journalism — it rang a “bell” to those who still carried on with a “journalistic consciousness”.

Another example is the Golden Dawn case. Not until international organisations and media outlets shed a light on the role of the neo-nazis, did mainstream media “discover” the phenomenon and attempt to report on it.

I’ d like to add that several social issues like the right to citizenship or human rights abuses against immigrants, asylum seekers and other minorities, were not reported at all or they were downplayed by “right wing” newspapers.

Index: So, what about the future?

Katsimi: After the public broadcaster’s shutdown and the launch of the new state-run broadcaster NERIT, all I see is that the government succeeded in suppressing alternative opinions and controlling, more than ever, public broadcasting.

On the other hand, there is still hope in citizen journalism and in new media collectives that are not bound to big economic interests and are free to report on social issues mainstream media neglect.

This article was published on Wednesday, 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org