06 Aug 14 | Azerbaijan Statements, News and features, Statements

Rasul Jafarov, Arif Yunus and Leyla Yunus (Photos: Rasul Jafarov (© IRFS), Arif and Leyla Yunus (© HRHN))

60 NGOs from 13 Human Rights Houses call upon the Azerbaijani authorities, in their joint letter to President Ilham Aliyev, to immediately and unconditionally release Leyla Yunus, Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov, and lift all charges held against them. The NGOs also repeat their previous call to release Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli, and join calls for the release of Hasan Huseynli.

On 28 April 2014 Leyla Yunus, Director of the Institute for Peace and Democrac, and her husband historian Arif Yunus, were prevented from leaving the country at Baku’s airport. Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif Yunus were arrested on 30 July 2014. On that day, Leyla Yunus was sentenced to 3-months pre-trial detention, whilst her husband was placed under police guard and not allowed to leave Baku. The charges brought against Leyla Yunus are those of state treason (article 274 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan), large-scale fraud (article 178.3.2), forgery (article 320), tax evasion (article 213), and illegal business (article 192). Arif Yunus was arrested on 5 August 2014 and also sentenced to 3-months pre-trial detention.

The NGOs state in their joint letter to President Aliyev of 5 August 2014 that they are in particular concerned about Leyla Yunus’ health whilst in detention. She suffers from diabetes and needs appropriate medication, as well as arrangements to eat at certain times, necessary to control the illness. We worry that the conditions in detention will have a detrimental effect on her health condition, as it appears that she is to date not provided with adequate health care.

In July 2014, the bank accounts of, amongst others, human rights defender Rasul Jafarov were frozen as part of a broader investigation into numerous NGO’s. On 25 July he was refused to leave the country. Rasul Jafarov was arrested on 2 August 2014, and sentenced to 3 months pre-trial detention on charges of tax evasion (article 213 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Azerbaijan), illegal business (article 192) and abuse of authority (article 308.2).

On 14 July 2014, Hasan Huseynli, was sentenced to 6 years in prison. He was convicted on charges of armed hooliganism and unlawfully carrying a cold weapon.

The right to freedom of association is at the heart of the charges held against these human rights defenders. In essence they are deprived of their right to work in the defence of human rights. While registration of NGOs and grants to NGOs has become mandatory in Azerbaijan, authorities continue deny registration. Independent NGOs face continuous investigations and human rights defenders are being banned from travelling abroad, depending on their willingness to find agreements with the government, including agreements on their professional activities and their public statements.

Restrictions to laws affecting the right to freedom of association have been widely criticised since October 2011. Such legislation de facto criminalises human rights defenders in Azerbaijan, not for their wrong doing, but rather for the fact that working for an NGO, which does not have the blessing of the government, has become difficult in Azerbaijan. United Nations experts stated ahead of the Presidential elections that they “observed since 2011 a worrying trend of legislation which has narrowed considerably the space in which civil society and defenders operate in Azerbaijan.” The order given to the Human Rights House Azerbaijan in March 2011 to cease all its activities is a consequence of such policies.

The NGOs call upon the Azerbaijani authorities, in their joint letter to President Ilham Aliyev of 5 August 2014, to immediately and unconditionally release Leyla Yunus, Arif Yunus, Rasul Jafarov, and lift all charges held against them. The NGOs see this pre-trial detention of Leyla Yunus, Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov as a way to silence them. The NGOs also repeat their previous call to release Anar Mammadli and Bashir Suleymanli, and join calls for the release of Hasan Huseynli.

The NGOs further call upon the Azerbaijani authorities to take appropriate measures to put an end to the attacks, detention and harassment of human rights defenders, journalists and activists, and to take steps in order to foster a safe environment for them, in line with Azerbaijan’s international obligations and commitments, especially as the chair of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.

Signed by:

Human Rights House Azerbaijan (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Association for the Protection of Women’s Rights

- Azerbaijan Lawyers Association

- Institute for Reporters’ Safety and Freedom

- Legal Education Society

- Media Rights Institute

- Society for Humanitarian Research

- Women Association for Rational Development

Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House in exile, Vilnius (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Belarusian Association of Journalists

- Belarusian Helsinki Committee

- City Public Association “Centar Supolnaść”

- Human Rights Centre “Viasna”

Human Rights House Belgrade (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Belgrade Centre for Human Rights

Human Rights House Kiev (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on Law-Enforcement

- Human Rights Information Centre

- Center for Civil Liberties

- Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

- Ukrainian Legal Aid Foundation

Human Rights House London (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Article 19

- Index on Censorship

Human Rights House Sarajevo (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Human Rights House Tbilisi (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Article 42 of the Constitution

- Georgian Centre for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims

- Human Rights Centre

Human Rights House Oslo (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Human Rights House Foundation

- Norwegian Burma Committee

- Norwegian Helsinki Committee

Human Rights House Voronezh (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Charitable Foundation

- Civic Initiatives Development Centre

- Confederation of Free Labor

- For Ecological and Social Justice

- Free University

- Golos

- Interregional Trade Union of Literary Men

- Lawyers for labor rights

- Memorial

- Ms. Olga Gnezdilova

- Soldiers Mothers of Russia

- Voronezh Journalist Club

- Voronezh-Chernozemie

- Youth Human Rights Movement

Human Rights House Yerevan (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly-Vanadzor

- Helsinki Association for Human Rights

- Journalists’ Club “Asparez”

- Public Information and Need of Knowledge NGO

- Shahkhatun

- Women’s Resource Center

Human Rights House Zagreb (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- APEO/UPIM Association for Promotion of Equal Opportunities for People with Disabilities

- B.a.B.e.

- CMS – Centre for Peace Studies

- Documenta – Centre for Dealing with the Past

- GOLJP – Civic Committee for Human Rights

- Svitanje – Association for Protection and Promotion of Mental Health

The Rafto House in Bergen, Norway (on behalf of the following NGOs):

The House of the Helsinki Foundation For Human Rights, Poland (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights

Election Monitoring and Democracy Studies Center, Azerbaijan

Foundation “Multiethnic Resource Center for Civic Education Development”, Georgia

People in Need, Czech Republic

Public Movement Multinational, Georgia

Public Association for Assistance to Free Economy, Azerbaijan

Public Union of Democracy and Human Rights Resource Centre, Azerbaijan

This statement was originally posted on Aug 5, 2014 at http://humanrightshouse.org/Articles/20321.html

06 Aug 14 | Academic Freedom, News and features, United States

(Photo: Georden West)

A women’s university considered to be one of the most restrictive on transgender issues in the US is reconsidering its approach.

Rated as the strictest of any US university on transgender policies by the Chronicle of Higher Education, Hollins University currently forbids students from making any legal or biological step toward becoming male.

But a university official says the school is considering the addition of gender-neutral bathrooms to make the campus more welcoming and to support its students on the transgender spectrum.

Founded in 1842, Hollins University has attracted many now famous names including writers Annie Dillard and Margaret Wise Brown, US Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey and White House correspondent Ann Compton.

However, in the past few years its restrictive policy on the retention of transgender students has attracted national attention from activists and academics.

The current policy states that any student who “’self identifies’ as a male and initiates any of the following processes: 1) begins hormone therapy with the intent to transform from female to male, 2) undergoes any surgical process (procedure) to transform from female to male or 3) changes her name legally with the intent of identifying herself as a man,” will not be allowed to graduate from the university. After substantial criticism, Hollins agreed to re-evaluate its policy and drafted a new version in 2013. The current policy also maintains the university’s position against allowing female-to-male students and adds that any student who chooses to undergo sex reassignment “will be helped [by university officials] to transfer to another institution.”

The issue of gender-neutral spaces has become increasingly contentious and polarising with the emergence of a new transgender-equality group on campus called EqualiT*. Its appearance was marked by mysterious flyers in bathroom stalls and on announcement boards calling for the addition of gender-neutral bathrooms. Soon a blog and a Facebook page also appeared, and the group began to stage events, including a candlelight vigil to commemorate Transgender Awareness Day. Due to the sensitive nature of the organisation, the group has remained mainly anonymous in hopes of protecting its transgender members. Some students fear that, if exposed, transgender students will lose their scholarships or be expelled from the university. The university has not taken any action against students who are legally and biologically female, but some students say they self-censor because they are worried about what may happen.

With a student population of less than 600, low retention rates and a high-priced tuition cost of over $46,000 per year, critics question whether the university can afford to alienate any portion of its student demographic.

The forced removal of transgender students from Hollins presents not only financial and academic challenges but a threat to students’ safety. Forty-five per cent of transgender university students in the US reported experiencing verbal, physical or sexual abuse due to their gender identity according to a 2011 study by the National Center for Transgender Equality. Many transgender students attending all-female institutions regard the environment as safe and welcoming and fear for their safety in transferring to a coeducational environment. A study in 2006 revealed that one in twelve transgender people is murdered in the United States, and many more experience severe verbal harassment and physical violence.

“I believe creating gender neutral safe spaces should be at the forefront of the actions Hollins is taking right now,” said Cal Thompson, a transgender student who graduated in the spring of 2014. “Everyone needs a safe space for personal business. We don’t want to use the gendered bathrooms just as badly as the cisgendered don’t want us.”

Despite the relative safety transgender students feel at Hollins, students still find the university a challenging place to explore individual gender identities. Perhaps one of the most substantial of these challenges is in the lack of gender-neutral spaces, specifically bathrooms. Because of the requirement for students to remain female during their time at Hollins, students who identify as transgender are prohibited from using the men’s restroom.

“Using the bathroom at Hollins was uncomfortable,” said Lee Collie, a 2013 graduate, known as Leanna during his time at Hollins. “Even if you flip the sign to ‘male’ when you walk in, girls walked in all the time and said, ‘Oh, it’s just Lee,’ which meant that they didn’t really see me as a male.”

Hollins’ Dean of Students, Patty O’Toole told Index, “As we continue to renovate our facilities, when appropriate we are considering developing gender-neutral bathrooms.” With regards to facilities in residence halls, students in each community can collectively determine facility-usage and associated language, O’Toole said. Bathroom usage in residence halls is indicated by a paper sign for each hall’s bathroom, which can be flipped over to indicate different users. Thus, some facilities may be labelled with “men” and “women,” while others may use “residents” and “guests.” No other official steps have been taken to utilise gender-neutral language.

A number of students disagree with the student organisation’s position, including current student Deborah Birch, class of 2016. “I don’t think that there should gender-neutral bathrooms on campus. You apply to Hollins knowing that it is an all-women’s institution. If want to change your biological make-up to transition from female to male, you should choose to attend another institution.”

Though transgender graduate Lee Collie likes the idea of gender-neutral restrooms, he also worries about respecting the larger campus community, specifically those with opposing ideals. “I would probably limit them to the dorms or specific floors, because we have professors and visitors who may not feel comfortable.”

Hollins is not the only US institution struggling over whether it should create gender-neutral bathrooms. Recently Illinois State University has attracted media attention through its decision to change its family bathroom to an all-gender bathroom. Although the change was not specifically requested by any students or faculty, ISU officials made the change in efforts to remain proactive and to promote inclusivity among all members of campus. Over 150 universities across the United States have instituted similar changes in campus facilities, including New York University, Ohio State University and UCLA. Even fellow women’s universities like Smith College in Massachusetts and Agnes Scott College in Georgia have begun to embrace the issue, with the addition of gender-neutral restrooms and more progressive policies.

Collie, a former vice president of the university’s student government association, stated that the policy at Hollins may be strict, but he is glad that Hollins has a policy and acknowledges the existence of transgender students on campus. Other women’s universities have yet to adopt any policy on the matter.

Dean of Students, Patty O’Toole explained that the 2011 policy was originally created by the university’s Board of Trustees in response to students on the transgender spectrum who were seeking a written policy. “Hollins wanted to support those students. The focus of the policy is not strictness but clarifying our institutional mission.”

Collie supported the university’s actions and its mission as a women’s institution, despite the personal challenges he faced, and related the support and camaraderie he experienced at the university. “Hollins has never punished me for being or identifying as male. It isn’t that they’re trying to stop someone from being who they really are, but it is Hollins standing true to itself as well.”

This article was published on August 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

05 Aug 14 | Australia, Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

(Image: Shutterstock)

A piece of proposed legislation in the senate in Australia is attempting to wrestle with the legacy of the Snowden leaks with potential implications for media freedom.

In late 2013 information was released to the world that revealed the depth and breadth of the covert architecture in place to monitor and harvest personal data. The unprecedented capabilities and actions of surveillance agencies the world over ignited debate around the nature of privacy in our digital age. But the emergence was not manufactured by the security apparatus or by governments; it was the result of leaked information being published by the press.

Now, a new law proposed by Attorney-General, George Brandis, the National Security Legislation Amendment Bill (no.1) outlines a number of reforms to “modernise and improve” Australia’s capabilities to tackle national security threats. If passed, it could have significant implications for Australian media.

The creation of Special Intelligence Operations (SIO) – covert operations that offer limited immunity for its participants to engage in unlawful conduct – as well as the expansion of computer access warrants are among the sweeping reforms contained within the bill.

Further reforms outline new offences for “unauthorised dealings with an intelligence-related record, including copying, transcription, removal and retention”. But as highlighted by publications such as The Guardian, the Australian Lawyers Alliance (ALA) and members of the opposition, including Greens Senator Scott Ludlam, the bill opens up the possibility for criminal culpability to lie beyond the security operatives dealing with intelligence-related records, to journalists and media outlets who report on information they receive about SIOs. The bill’s explanatory memorandum states that the offence applies to:

“[D]isclosures by any person, including participants in an SIO, other persons to whom information about an SIO has been communicated in an official capacity, and persons who are the recipients of an unauthorised disclosure of information, should they engage in any subsequent disclosure.”

The transcript of the bill’s second reading demonstrates Brandis’s opinion of Snowden, dismissing him as a “so-called ‘trusted insider’” (he has previously referred to the NSA whistle-blower as an “American traitor”). But while he has stated that the bill is not intended to threaten media outlets or limit media freedom, the wording of the bill has set alarm bells ringing. Quoted in The Guardian, ALA spokesperson Greg Barns stated that this bill “takes the Snowden clause and makes it a Snowden/Assange/Guardian/New York Times clause.”

He goes further, explaining how the structure of approving SIOs, threatens media coverage: “ASIO [Australian Security Intelligence Organisation] could secretly declare many future cases to be special intelligence operations. This would trigger the option to prosecute journalists who subsequently discover and report on aspects of these operations.” This lack of clarity in the wording of the bill, as well as the limited oversight as to how the bill can be used – political appointees have the final say – sets a precedent for potential restrictions on media freedom both in Australia and, as a template for action, globally.

The size and scale of the surveillance network, involving governments worldwide, most notably the “five eyes” countries, the US, UK, Canada, New Zealand and Australia raises uncomfortable questions, with no forthcoming answers. The reforms proposed by Brandis seem to suggest that the best way of satisfying these questions is to ensure they are not asked in the first place.

Restricted by inadequate whistle-blower protections, due in part to his status as a private contractor, as well as the national security implications of the leaked documents, reaching out to the media provided to be the sole outlet for Ed Snowden. But it seems now that it could be the media who will be punished for such inadequate protections.

After two readings in the Senate, the bill is poised to be debated in September. And although Brandis has set his sights elsewhere, having mentioned data retention in an interview to ABC, the precedent set by Australia, were this bill to pass, could resonate throughout the world. Scott Ludlam outlined his concern: “I can’t see anything that conditions it or carves out any public interest disclosures. I can’t see anything that would protect journalists.”

This concern does not seem to be shared across the political spectrum. The Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott called on journalists for a “sense of responsibility, a sense of national interest”, and the Liberal senator, Cory Bernardi went further by stating that “we need to make sure the press are free to report within the constraints of what is in, I’d say, the national interest”.

Would protecting national interests include the refusal to publish information surrounding the allegations that the Defence Signals Directorate, or DSD, (now called the Australian Signals Directorate) attempted to monitor the calls of the Indonesian president, his wife and senior politicians? What about the DSD’s desire to share harvested online data (or “unminimised” metadata) with other governments without any privacy restraints?

If decisions such as these are left to those who define the role of the press as one of propagating national interests, then the freedom that Bernadi speaks of is surely no freedom at all.

This article was published on August 5, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

04 Aug 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, Europe and Central Asia, News and features

(Photo: National Endowment for Democracy)

Azerbaijani human rights activist Rasul Jafarov has been charged with tax evasion, illegal entrepreneurship and power abuse and sentenced to three months of pre-trial detention. Jafarov’s detention follows the arrest last week of Leyla Yunus and the disappearance of the print edition of Azadliq from the streets of Baku. Arif Yunus was put under a three month pretrial detention on 5 Aug.

Jafarov, an Index contributor, is a prominent campaigner and critic of Azerbaijan’s government, led by President Ilham Aliyev. He has worked on putting together a detailed list of the country’s some 140 political prisoners and was one of the organisers behind the Sing for Democracy campaign, in connection with the 2012 Eurovision final in Baku. He was charged with three articles of the Penal Code by Rasul Nasimi district court in the capital Baku, following interrogation at the Prosecutor General’s office. Last week he was handed down a travel ban.

His arrest comes days after fellow human rights defenders Leyla Yunus and her husband Arif were charged with crimes including high treason. Last week, Azadliq, of the country’s few remaining independent newspapers, was also forced to suspend publication of its print edition due to financial troubles. The charges against Jafarov are the same as those that in May saw Anar Mammadli, another prominent human rights defender, sentenced to 5.5 years in prison.

The Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS), an Azerbaijani press freedom organisation, said Jafarov’s arrest is “part of a dedicated campaign aimed at suspension of activities of unregistered NGOs in Azerbaijan”. Registering NGOs in Azerbaijan is difficult — Jafarov has reportedly attempted to register his organisation Human Rights Club a number of times without success. As a result, many groups operate without a licence.

There has recently been an escalation in the targeting of opposition voices in Azerbaijan, according to IRFS, who say this crackdown has included state-controlled media smear campaign, raids on NGO offices, confiscation of equipment, suspension of NGO bank accounts, and intimidation and legal pursuit of NGO workers.

In May, Azerbaijan assumed chairmanship of the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers, whose tasks include “ensure[ing] that member states comply with the judgments and certain decisions of the European Court of Human Rights”.

“Further deterioration of the situation with fundamental rights and freedoms, as well as repressions against the civil society is incompatible with Azerbaijan’s international commitments, especially in light of its current presidency in the Council of Europe,” said the Civic Solidarity Platform, a network of 60 human rights NGOs of the OSCE region, in a statement.

“We know that the charges against those brave human rights defenders are politically motivated. The authorities want to silence those holding the country to its international obligations and commitments, including within the Council of Europe” said Maria Dahle, Executive Director of the Human Rights House Network.

Index Reports: Locking up free expression: Azerbaijan silences critical voices (Oct 2013) | Running Scared: Azerbaijan’s silenced voices (Mar 2012)

An earlier version of this article stated that Arif Yunus had been arrested last week. This was incorrect. Yunus was arrested on 5 Aug and sentenced to a three month pretrial detention.

This article was posted on August 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

04 Aug 14 | Awards, Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

Index Award winning Azadliq newspaper was forced into cancelling its print run last week with little hope of restoring its publication.

It is not that easy to get to the editorial office of Azadliq in Baku. Once you enter the building of Azerbaijan Publishing House, a police officer, who sits close to a statue of Heydar Aliyev, the late “father of the nation” and the actual father of the incumbent president Ilham Aliyev, asks you to call the office of the newspaper to get someone to pick you up downstairs. “Everyone in Baku knows their number,” an old lady in the phone room says as she tells me how to reach Azadliq.

Rahim Haciyev, an acting editor of the daily, smiles as he greets me, and leads to the top floor of the building that looks like a shattered remnant of the Soviet past. We pass a dark and neglected corridor that seems to be last painted around 1989 – the year Azadliq was launched.

The last day of July 2014 can become the end of what was the last independent daily in Azerbaijan as it was forced into suspension of publication.

“We owe 20,000 manat (about £15,000) to the publishing house, and they refuse to print our newspaper unless we pay the debt. But we are not able to, because we don’t get money for the newspaper sales. Gasid, the state-owned press distribution company, owes us 70,000 manat (about £53,000), which should be enough to cover our debts and operation costs. Its general manager is an MP and a member of the ruling party – and they just won’t pay us,” says Rahim Haciyev.

The authorities of Azerbaijan have used economic pressure to silence one of the last critical voices in the country. Last year the newspaper was a target of defamation suits that have resulted in £52,000 in fines, which were followed by bans against selling the paper at tube stations and on the streets of Baku. Thus, Azadliq lost sales of 3,500 copies daily – and with the official distribution network refusing to pay for the copies they sell, it has resulted in a complete blockade of any revenue streams. The State Press Support Fund refused to support the paper as well.

“The authorities have tried to stifle us for a long time, and it looks like they have finally succeeded. I don’t see them letting us go back to print. The only chance is strong pressure from the West, but I don’t expect this to happen. The Western democracies are now preoccupied with weakening the influence of Russia in the region, so it is unlikely they are going to put too much pressure on its neighbouring countries,” says Haciyev.

Azadliq’s editor also sees pressuring of the paper as a part of a wider campaign of the Azerbaijani authorities aimed at silencing of the country’s civil society. Two well-known human rights defenders, Leyla Yunus and Rasul Jafarov, were arrested last week; they will be detained pending trial for three months each.

“At the moment, when repressions against the civil society and human rights activists are getting tougher, the last thing they need is a critical newspaper that spreads the word about their clampdown. And we were the last daily that reported on those cases,” Haciyev points out.

Azadliq’s editorial team keeps working, although they have not been paid for two and a half months. The paper’s website, which is one of the most popular news source online in Azerbaijan, is still updated, but nobody knows for how long.

“Azadliq” means “freedom” is Azerbaijani. There is less and less freedom in the country that looks set to take a sad lead on the number of closed down media outlets and human rights activists in jail.

This article was posted on August 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

01 Aug 14 | Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, Turkey

Photo illustration: Shutterstock

Since the beginning of this year, cases of assault against journalists, legal threats and lay offs worsened Turkey’s already precarious state of press freedom.

In May, Freedom House ranked Turkey’s media climate “not free.” The Istanbul-based non-profit news website Bianet publishes quarterly media monitoring reports on press freedom breaches within Turkey. Along with new fines against media outlets and other ominous restrictions, the most recent report shows that physical assault against journalists increased over the last three months. According to the new report, 54 journalists were victims of assault between April and June. Bianet’s previous report documents “at least” 40 accounts between January and March.

Erol Önderoğlu, author of Bianet’s media reports, attributes the increased number of assaults this spring to recent demonstrations where journalists were injured. This May, protestors commemorated the first anniversary of the Gezi Park demonstrations, just a few weeks after large protests took place on May 1. Önderoğlu says police and other security officers are more prone to use violence at protests. “They think they have the right to exert a certain violence against demonstrators,” he says. Önderoğlu sees last year’s Gezi Park protests as a turning point for this kind of aggression towards journalists at demonstrations. Since then, Önderoğlu says, police officers became the main source of violent assault against journalists.

At May 1 protests in Istanbul, at least twelve journalists were injured while reporting. One editor for the news website t24 was detained by police for hours. Violence against journalists erupted again during the Gezi commemorations this year. While reporting live from the protests, CNN correspondent Ivan Watson was harassed by plainclothes security officers who demanded to see his passport. Watson and his crew were then detained and Watson tweeted that he was kneed while in police custody.

Many journalists don’t file legal complaints after they’ve been assaulted. According to Önderoğlu, especially journalists working for mainstream news outlets feel their own jobs may be threatened if they speak out against police. “They have this feeling that by condemning civil servants and police officers for using force, they are in a way putting the board and the directors of their own media organization in a bad position,” Önderoğlu says, adding that because of the lack of editorial independence in Turkey, conflicts with government can lead to journalists being fired. Earlier this year, the extent of Prime Minister Erdoğan’s influence over some media organizations was revealed by leaked phone conversations between Erdoğan and the owners of media outlets, including the newspaper Milliyet and broadcaster Habertürk.

The journalists Ahmet Şık, Onur Erem and Ender Ergün did file a complaint over abuse of authority after being assaulted during the 2013 Gezi Park protests. Six months later, their cases were rejected by an Istanbul prosecutor. Bianet reported that 153 journalists were injured during the Gezi Park protests. There still has not been an investigation into those injuries, and Önderoğlu sees the rejection of Şık, Erem and Ergün’s cases as a bad precedent for assaulted journalists seeking justice. “We need not only the stop of police aggression,” Önderoğlu says, “but also the end of impunity against policemen of such accusations.”

More reports from Turkey via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

Turkey: Broadcaster threatens to stop covering presidential candidate

Turkey: Physical assaults on journalists increase

Turkey: Media monitoring agency revokes license for Germany-based broadcaster

Turkey: Constitutional Court rules investigation into Hrant Dink’s assassination violated family’s rights

Turkey: Prime Minister files legal complainst against newspaper editor

This article was posted on August 1, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

01 Aug 14 | Digital Freedom, India, News and features

The Global Network Initiative (GNI) and the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMA) have launched an interactive slide show exploring how India’s internet and technology laws are holding back economic innovation and freedom of expression.

India, which represents the third largest population of internet users in the world, is at crossroads: while the country protects free speech in its constitution, restrictive laws have undermined Indias record on freedom of expression.

Constraints on digital freedom have caused much controversy and debate in India, and some of the biggest web host companies, such as Google, Yahoo and Facebook, have faced court cases and criminal charges for failing to remove what is deemed objectionable content. The main threat to free expression online in India stems from specific laws: most notorious among them the 2000 Information Technology Act (IT Act) and its post-Mumbai attack amendments in 2008 that introduced new regulations around offence and national security.

In November 2013, Index launched a report exploring the main challenges and threats to online freedom of expression in India, including takedown, filtering and blocking policies, and the criminalisation of online speech.

This article was posted on Aug 1, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jul 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News

One of the few remaining independent media outlets in Azerbaijan, the 2014 Index on Censorship Guardian Journalism Award-winning newspaper Azadliq has been forced to suspend publication due to an ongoing financial crisis. This comes just a day after the government of Azerbaijan targeted prominent human rights defenders Leyla and Arif Yunus and Rasul Jafarov. Yunus and her husband have been detained for three months as prosecutors build a case around charges that include high treason. Jafarov has been banned from traveling.

The paper’s Editor-in-Chief Rahim Haciyev told Contact AZ that without an immediate payment of 20,000 manat (£15,105.39) to its printer, the latest issue would not be produced. The paper’s government-backed distributor, which according to Haciyev owes Azadliq 70,000 manat (£52,868.86), has refused. This is not the first time that Azadliq, which has reported on government corruption and cronyism, has faced a financial cliff.

Read more about Azadliq here.

Index Reports: Locking up free expression: Azerbaijan silences critical voices (Oct 2013) | Running Scared: Azerbaijan’s silenced voices (Mar 2012)

This article was posted on July 31, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jul 14 | Ireland, News and features, Pakistan, Religion and Culture

It was, apparently, the posting of a “blasphemous image” on Facebook that led an angry mob to burn down houses with children inside them.

It’s been suggested that it was a picture of the Kaaba, Islam’s holiest site, that provoked the mob in Gujranwala in Pakistan. They rallied last Sunday at Arafat colony, home of 17 families belonging to the Ahmadi sect. As police stood by, houses were looted and torched. At the end of the night, a woman in her 50s, Bushra Bibi, and her granddaughters Hira and Kainat, an eight-month-old baby, were dead. None of them had anything to do with the blasphemous Facebook post.

Was the image even blasphemous? In some ways, it doesn’t really matter. What matters was that it was posted by an Ahmadi, whose very existence is condemned by the Pakistani penal code.

Ahmadiyya emerged in India in the late 19th century. It is a small sect based on the belief that its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, was, in fact, the Mahdi of Muslim tradition. This teaching is rejected by Orthodox Sunni Islam.

In Pakistan, this means that being a member of the Ahmadiyya sect is dangerous. The law says you cannot describe yourself as Muslim. You cannot exchange Muslim greetings. You cannot describe your call to prayer as a Muslim call to prayer. You cannot describe your place of worship as a Masjid.

Any Ahmadi who “any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims” can be imprisoned for up to three years.

Ahmadis suffer disproportionately from Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, but they are not the only ones who suffer. Accusations of blasphemy are frequently levelled at members of other minorities and at mainstream Muslims too. Often, this is done out of sheer spite. Often it is done to settle scores.

As the New Statesman’s Samira Shackle has pointed out, amid the chaos and fear generated by the law, it’s often difficult to find out what people are actually supposed to have done, as media hesitate to repeat the alleged blasphemy lest they themselves be accused of the crime.

The fevered atmosphere created by the laws mean that to oppose them can be fatal. In Janury 2011, Punjab governor Salmaan Taseer was killed by his own bodyguard after he pledged to support a Christian woman, Aasia Bibi, who had been accused of the crime. Taseer’s assassin claimed that the governor had been an “apostate”. He was widely praised by the religious establishment. Three months later, Minority Affairs Minister Shahbaz Bhatti was killed, apparently because of his belief that the blasphemy law should be changed.

Meanwhile, an amendment proposed by Taseer’s colleague Sherry Rehman, which would have abolished the death penalty for blasphemy, was dropped. Rehman was posted to diplomatic service in the United States later that year, amid allegations that she herself had committed some kind of blasphemy.

The number of blasphemy cases is steadily rising, and Human Rights Watch recently claimed that 18 people are on death row after being found guilty of defaming the prophet Muhammad, though no one has as yet been executed.

The laws may seem archaic, but they are in fact utterly modern. While some of South Asia’s laws on religious offence date back to the Raj, the laws relating to the Ahmadi, and the law making insulting Muhammad a capital offence only emerged in the 1980s, as part of General Zia’s attempts to shore up his religious credentials.

The sad fact is this Pakistan’s new enthusiasm for blasphemy laws is not an international aberration. Nor is this a trend confined to confessional Islamic states.

Ireland’s 2009 Defamation Act introduced a 25,000 Euro fine for the publication of “blasphemous matter”. According to the Act , “a person publishes or utters blasphemous matter if—

(a) he or she publishes or utters matter that is grossly abusive or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion, thereby causing outrage among a substantial number of the adherents of that religion, and

(b) he or she intends, by the publication or utterance of the matter concerned, to cause such outrage.”

Note how similar the wording is to the Pakistani law forbidding Ahmadis from offending Muslims. The Pakistani government repaid the compliment when, along with other members of the Organisation of Islamic Conference, it attempted to force the UN to recognise “religious defamation” as a crime, lifting text from the Irish act. Pakistan claimed, grotesquely, that criminalising blasphemy was about preventing discrimination. Cast your eyes back once again to how its blasphemy provisions treat Ahmadis.

Across Europe, more and more blasphemy cases are emerging. In January of this year, a Greek man was sentenced to 10 months for setting up a Facebook page mocking an Orthodox cleric. In 2012, Polish singer Doda was fined for suggesting that the Bible read like it was written by someone drunk and “smoking some herbs”. The trial of Pussy Riot in Russia was heavy with talk of sacrilege.

We tend to believe that the world is moving inexorably toward a secular settlement. The unintended upshot of this prevalent belief is that organised religions, even in countries like Pakistan, get to portray themselves as weak people who need to be protected from extinction, even as they wield power of life and death over people.

Religious persecution is real, and should be fought. Freedom of belief is a basic right. But blasphemy laws protect only power, and never people.

This article was posted on July 31, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

31 Jul 14 | Mali, News and features, Religion and Culture

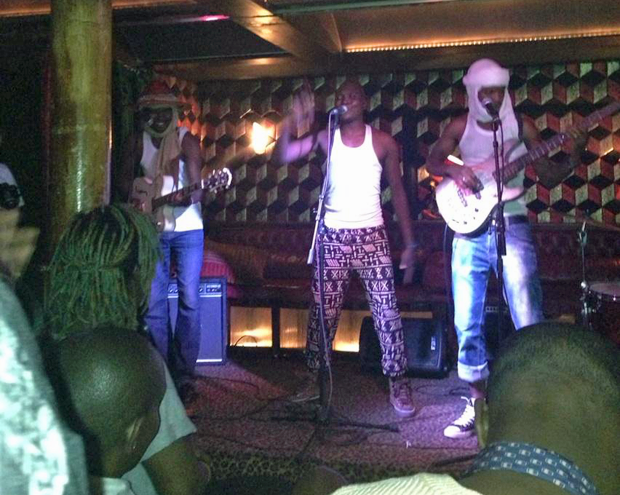

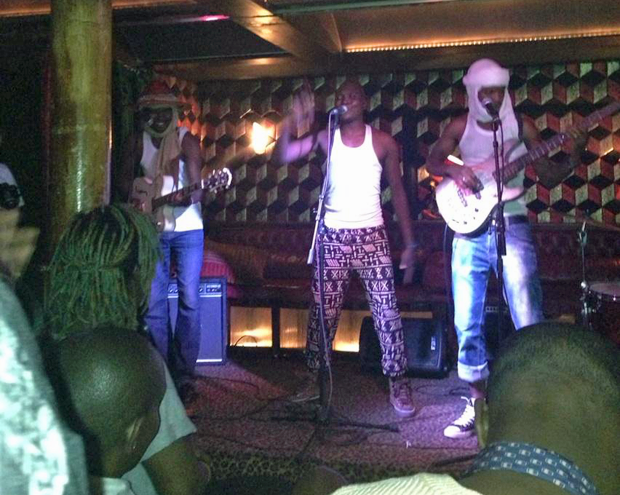

Songhoy Blues, performing in London, asked the audience to imagine music being banned in the UK.

Aliou Touré, lead vocalist of the Malian band Songhoy Blues, introduced their concert in London by talking about the challenges musicians face in Mali, where music was banned by a local armed Islamist group in the north of the country in 2012.

“It is liberating to be able to perform tonight because in my country, I do not have the same freedom of expression,” Touré added before the kick off.

As the concert rolled on, one could easily forget that Songhoy Blues — who are touring in the UK ahead of their album launch later in the year — were deprived from playing music at home.

In September 2013, documentary filmmaker Johanna Schwartz wrote for Index on Censorship magazine on the censorship and persecution that musicians in Mali have faced since the ban on music: “There is a fear that freedoms may not be so easily restored,” wrote Schwartz. Today, although the ban has been theoretically lifted, the fear remains. “Because of the violence, it is still impossible for me to play music in my hometown,” said Touré, who is from the northern city Gao.

Like thousands of refugees, Touré left for Bamako amid escalating violence.

In the capital city, Touré and other musician friends — Garba, Oumar and Nathanael — from the north decided to form a band. The very creation of their band is an act of hope and resistance: “Somehow, the ban on music played in our favour because it’s only after we left the north that we came together and formed Songhoy Blues,” explained Touré.

The band is now based in Bamako, where the members long for the weekend to perform in local bars. But as music was being driven out of the country — even those with musical ringtones on their mobile phones faced crackdowns — many musicians fled Mali. They Will Have to Kill Us First, Schwartz’s feature-length documentary, follows the story of Mali’s musical superstars as they fight for their right to sing.

At this time, They Will Have to Kill Us First is in the final stages of shooting, and it is still uncertain if Songhoy Blues and the other Malian musicians in exile will feel safe enough to return to home.

This article was posted on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Jul 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

UPDATE 30 July 17:30 pm

Leyla Yunus has been charged with “high treason (article 274), tax evasion (article 213), illegal entrepreneurship (article 192), forged documentation (article 320) and fraud (article 178.3.2)”, reports Meydan TV. She has also been given three months of pre-trial detention, according to Azerbaijani journalist Khadija Ismayilova. Her husband Arif Yunus is reportedly facing two charges; state betrayal (article 274) and fraud.

—

Azerbaijani human rights activist Leyla Yunus has been taken to the prosecutor’s office in Baku for questioning, local media reported.

While on her way to a conference this morning, three men entered her taxi and confiscated her and her driver’s mobile phones. According to her husband Arif Yunus, she is not allowed to see her lawyer.

“It is likely [they] are going to try and arrest her as part of Mirkadirov’s case. It is also likely I too will be arrested,” he told BBC Azerbaijan. He was referring to the case of journalist Rauf Mirkadirov, who was arrested in April and charged with espionage, believed to be linked to his contact with Armenian civil society. Leyla Yunus has spoken out in support of him. Mr. Yunus also said people were trying to break into the couple’s apartment this morning.

Leyla Yunus is the director of the Peace and Democracy Institute, which among other things works to establish rule of law in Azerbaijan. She has previously been targeted by authorities, including in April, when she and her husband were detained when trying to board a flight from Baku to Doha, Qatar. Azerbaijan has a notably poor record on human rights and civil liberties. According to recent figures, there are a 142 political prisoners in the country.

This article was posted on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Jul 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

Human rights defender Leyla Yunus was detained today in Baku.

It does not take a lot of time and effort to see that when it comes to Azerbaijan, views on the country’s freedom of expression record split in two. One–belonging to the president and his cronies–and their limited vision of reality combined with their persistent disregard of truth. And the other–the disregarded citizens–whose life is like an ongoing challenge full of obstacles–arrests, intimidation, murder, detention, beatings and blackmail to name a few. The levels of this marathon get harder to win and even then, there is a price to pay, sooner or later.

Stellar record vs stark reality

President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan says, “All fundamental freedoms are guaranteed in Azerbaijan. There are free media and free internet”. International advocates of free speech and their Azerbaijani supporters claim otherwise. Azerbaijan ranks 160th on the World Press Freedom Index; 183rd on the Freedom House Press Freedom Index; and “partly free” on Freedom on the Net report. The list only goes on.

Currently there are at least ten journalists in detention or prison serving long and heavy sentences. There are five bloggers, 8 youth activists and civil society representatives similarly in jail on trumped up charges. According to Amnesty International in 2013, there were at least 19 prisoners of conscience behind bars in Azerbaijan. Just today, human rights defender Leyla Yunus was detained in Baku.

And if the end result of a certain type of work/affiliation/statement/ or action isn’t necessarily time spent in jail, people are often threatened, intimidated, and even blackmailed- the list of “punishments” is creative and has no limits.

One of the country’s prominent investigative journalists, Khadija Ismayil had her share of a punishment for digging out the truth. In March of 2012, Ismayil received a package where not only was she sent a letter full of belittlement and blasphemy but also a video tape of intimate nature of her personal life.

More recently the head of a local NGO from Ganja, Hasan Huseynli was sentenced to six years in jail for allegedly stabbing a man on the street.

Only days following sentencing of Huseynli, two more young men and brothers Faraj and Siraj Kerimli were detained (Faraj was in fact kidnapped) and currently are held in pretrial detention for yet another trumped up charge–drugs possession and promotion of psychedelics via social networks.

There is free media and free speech only if its pro-government media and speech. Most of the working printed papers are either government sponsored, supported, or have cut a deal of some kind.

The internet is the remaining platform for free speech and even online there is surveillance and control. Some independent online outlets have been subject to attacks while users of social media tools are shown their correspondence on Facebook when detained for questioning.

And so the government continues to play the game of cat and mouse while disguising its dismal record of free speech and human rights under the pretext of being a young democracy, in conflict with a neighboring country, and thus occupied by far more pressing issues than addressing biased reports of international organizations on poor record of human rights and free speech.

Index Reports: Locking up free expression: Azerbaijan silences critical voices (Oct 2013) | Running Scared: Azerbaijan’s silenced voices (Mar 2012)

This article was published on July 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org