26 Jun 14 | About Index, Campaigns, Statements, Ukraine

President Petro Poroshenko

11 Bankova street

01220 Kyiv

Ukraine

26 June 2014

Mr President,

We, the undersigned members and partners of the Human Rights House Network (HRHN), condemned in the strongest terms human rights violations which took place throughout Ukraine since 29 November 2013, and now call upon you to extend the mandate of the International Criminal Court investigations (taking into account events in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine) and to ratify the Rome Statute, in order to encourage such investigations, as an essential part of bringing peace to the country.

We welcome the repeated pledges of Ukrainian authorities to investigate all human rights violations committed since 29 November 2013 and hold those accountable, throughout the country and irrespective of which side the violator belongs to in the ongoing armed conflict in East Ukraine. The current situation of impunity must end.

The International Criminal Court is the only international body able to not only document grave human rights violations, amounting to core international crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide), but also investigate individuals responsible for such crimes. In order to restore peace and strengthen trust into State institutions, those responsible for such human rights violations have to be held accountable. We have for a long time called for a comprehensive reform of the judicial system in the country, which still remains to be initiated. Unfortunately, the national judicial system now shows its limits and in our view it is clear that it does not have the adequate knowledge, independence and resources to investigate all human rights violations since 29 November 2013 throughout the country.

Therefore, it is necessary to activate the international justice system, based on the complementarity principle, to guarantee that investigation into core international crimes committed by all parties in Ukraine, including by members of law enforcement and State agents, is credible and transparent, bringing those responsible to justice.

The Court’s jurisdiction should however not be limited in time, as it is now. On 17 April 2014, the Government of Ukraine indeed lodged a declaration under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute accepting the jurisdiction of the ICC over crimes committed on its territory from 21 November 2013 to 22 February 2014.[3] We now call upon the Government to issue a declaration extending ICC jurisdiction from 21 November 2013 until the date of the entry into force of the Rome Statute for Ukraine.

We also call upon the authorities in Ukraine to accede to the Rome Statute as soon as possible. By doing this, Ukraine will make an important step to permanently depart from the culture of impunity that is prevailing.

In addition to the investigation into human rights violations, and action taken to end the use of violence in the country, Ukraine needs to undertake a massive reform of its legislation and practice in many fields. Ukraine’s law enforcement agencies have needed radical reform for a long time now: It is not about changing the names of institutions and units or about window-dressing, but about systemic changes, starting from the principles for establishing and structuring enforcement agencies, and ending with approaches to evaluating their performance.

We therefore support Ukraine’s efforts to propose a resolution at the United Nations Human Rights Council’s on-going session, although we deeply regret the draft resolution’s silence about the role of civil society in the country and the need for an investigation by the Court.

In Ukraine, human rights NGOs have proven their strong commitment to the rule of law and the respect of all human rights for all people, as well as their high level of professionalism and excellence. No country can build a sustainable future without full inclusion of civil society in decision-making, especially Ukraine in its present situation. Furthermore, States and leaders in all sectors of society must acknowledge publicly the important and legitimate role of human rights defenders in the promotion of human rights, democracy and rule of law, and avoid stigmatisation, as stated by the Human Rights Council resolution 22/6 of 21 March 2013.

Finally, we also welcome the reference in the draft resolution on Ukraine at the Human Rights Council to the extremely worrying human rights situation in Crimea and join Ukrainian authorities, the United Nations, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and other international voices, in condemning the enforcement of legislation of the Russian Federation on the territory of Crimea, at variance with the United Nations General Assembly resolution 68/262.

The role of civil society is essential in documenting human rights violations in Crimea and providing support to victims of such violations. A field mission has been launched by Ukrainian and Russian human rights defenders in co-operation, with which we expect full cooperation by all governmental agents in Ukraine.

On this background, we call upon you Mr President and the Government, with no further delay, to issue a declaration to extend the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court from 21 November 2013 until the date of Ukraine’s accession to the Rome Statute either through appeal of the competent body of the Government or by adopting the Draft Law #4081a.

We further call upon you to:

- Take all necessary measures to support the work of human rights NGOs, journalists and bloggers and other media, including by investigating any threats, intimidation, harassment and violence against them, including arbitrary detentions, abductions, attacks and killings;

- Strongly and publicly acknowledge the important and legitimate role of human rights defenders in the promotion of human rights, democracy and the rule of law as an essential component of ensuring their protection; In line with United Nations Human Rights Council resolution 22/6 of 21 March 2013, paragraph 5

- Ensure that the reform process in the country, as well as all dialogue about the future of the country, is inclusive and transparent, giving space to civil society.

Sincerely,

Human Rights House Kyiv (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Association of Ukrainian Human Rights Monitors on Law Enforcement (Association UMDPL)

- Centre for Civil Liberties

- Human Rights Information Center

- Institute of Mass Information

- Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group

- La Strada Ukraine

- NGO “For Professional Journalism” – Svidomo

- Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

Education Human Rights House Chernihiv (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Chernihiv Public Committee of Human Rights Protection

- Center of Humnistic Tehnologies “AHALAR”

- Center of Public Education “ALMENDA”

- Human Rights Center “Postup”

- Local Non-governmental Youth organizations М’АRТ

- Transcarpathian Public Center

- Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union

Azerbaijan Human Rights House (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Association for Protection of Women’s Rights – APWR

- Azerbaijan Human Rights Centre (AHRC)

- Institute for Peace and Democracy

- Human Rights Centre

- Legal Education Society

- Legal Protection and Awareness Society

- Media Rights Institute

- Public Union of Democracy Human Rights Resource Centre

- Women’s Association for Rational Development (WARD)

Barys Zvozskau Belarusian Human Rights House in exile, Vilnius

- Belarusian Association of Journalists

- Belarusian PEN Centre

- Belarusian Helsinki Committee

Human Rights House Belgrade (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Belgrade Centre for Human Rights

- Helsinki Committee for Human Rights, Serbia

- Human Rights House Belgrade and Lawyers’ Committee for Human Rights –YUCOM

Human Rights House London (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Index on Censorship

- Vivarta

Human Rights House Tbilisi (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Article 42 of the Constitution

- Caucasian Centre for Human Rights and Conflict Studies (CAUCASIA)

- Georgian Centre for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims

- Media Institute

- Human Rights Center

- Union Sapari – Family Without Violence

Human Rights House Oslo (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Human Rights House Foundation

- Norwegian Helsinki Committee

- Health and Human Rights Info

Human Rights House Voronezh (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Civic Initiatives Development Centre

- Confederation of Free Labor

- For Ecological and Social Justice

- Free University

- Golos

- Interregional Trade Union of Literary Men

- Lawyers for labor rights

- Memorial

- Ms. Olga Gnezdilova

- Soldiers Mothers of Russia

- Voronezh Journalist Club

- Roronezh – Chernozemie

- Youth Human Rights Movement

Human Rights House Yerevan (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly – Vanadzor

- Journalists’s Club Asparez

- Public Information and Need of Knowledge – PINK

Human Rights House Zagreb (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- APEO / UPIM Association for Promotion of Equal Opportunities for People with Disabilities

- B.a.B.e.

- CMS – Centre for Peace Studies

- Documenta – Centre for Dealing with the Past

- GOLJP – Civic Committee for Human Rights

- Svitanje – Association for Protection and Promotion of Mental Health

The Rafto House in Bergen – Norway (on behalf of the following NGOs):

The House of the Helsinki Foundation For Human Rights – Poland (on behalf of the following NGOs):

- Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, Poland

Copies have been sent to:

- Mr Oleksandr Turchynov, Chairman of Verkhovna Rada

- Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe

- Private Office of the Secretary General of the Council of Europe

- Chairman of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE)

- OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine

- OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

- United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine

- Delegation of the European Union in Ukraine

- Subcommittee on Human Rights of the European Parliament

- Diplomatic community in Kyiv, Brussels, Geneva and Strasbourg

- Various ministries of foreign affairs and parliamentary committees on foreign affairs

About the Human Rights House Network (www.humanrightshouse.org)

The Human Rights House Network (HRHN) unites 87 human rights NGOs joining forces in 18 independent Human Rights Houses in 13 countries in Western Balkans, Eastern Europe and South Caucasus, East and Horn of Africa, and Western Europe. HRHN’s mandate is to protect, empower and support human rights organisations locally and unite them in an international network of Human Rights Houses.

The Human Rights House Kyiv and the Education Human Rights House Chernihiv are members of HRHN. 10 independent Ukrainian human rights NGOs are members of both Human Rights Houses.

The Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF), based in Oslo (Norway) with an office in Geneva (Switzerland), is HRHN’s secretariat. HRHF is international partner of the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders and the emerging Balkan Network of Human Rights Defenders.

HRHF has consultative status with the United Nations and HRHN has participatory status with the Council of Europe.

26 Jun 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News and features

The Baku Court of Grave Crimes announced the verdict for the NIDA movement activists in May 2014. The human rights defenders Rashadat Akhundov, Zaur Gurbanly and Ilkin Rustamzadeh to 8 years’ imprisonment, Rashad Hasanov and Mamed Azizov – to 7.5 years. Protesters were detained and victimised by police. (Photo: Aziz Karimov / Demotix)

In a bleakly comic turn at the beginning of Ilham Aliyev’s address to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe this week, Assembly president Anne Brasseur asked press photographers to leave the chamber and reminded those present that they were not permitted to vocalise their approval or disapproval during the Azerbaijani dictator’s stand. It appeared that Brasseur hadn’t quite meant what she said, as in the end photographers at the front of the room were merely required to move their tripods to ensure everyone in the room could see Aliyev as he spoke.

Aliyev’s speech was given to mark the Azerbaijan’s taking up of the chair of the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers last month. And what a speech it was!

The man who promises to “turn initiatives into reality” (still no idea) told of Azerbaijan’s enormous progress in all fields, not just oil fields. He spoke of the country’s “very positive atmosphere” and listed the country’s great freedoms: freedom of political activity, freedom of expression, freedom of media… Azerbaijan was proud of these freedoms, he said. Azerbaijan knew that an uncensored internet and independent newspapers were important for democracy.

It was a lovely speech, and also one that contained barely a word of truth beyond the conjunctions. Aliyev may as well have praised the nation’s Quidditch team for defeating Ravenclaw on penalties at the World Cup. He could have told us about his new motorcar, and his adventures with Ratty, Mole and Badger, and been more believable.

Watching Aliyev, the only time one got the sense he even believed what he was saying himself was when discussing the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, and even then he was only drily insisting that the regions “geographical toponyms” (place names?) were Azeri in origin: All Your Geographical Toponyms Are Belong To Us, so to speak.

The truth about Azerbaijan is quite different from the picture painted by its president this week. As Human Rights Watch pointed out ahead of the Council of Europe speech, “In the past two years, Azerbaijani authorities have brought or threatened unfounded criminal charges against at least 40 political activists, journalists, bloggers, and human rights defenders, most of whom are behind bars.” Search for Azerbaijan stories on Index, and you will find more details of those arrests and abuses.

And this isn’t exactly obscure knowledge. People know three things about Azerbaijan: it has a lot of gas and oil; it takes Eurovision very seriously; and it has a poor human rights record. After his speech, Aliyev was confronted by Michael McNamara of the CoE socialist group, who quoted Amnesty’s statistic that there are currently 19 political prisoners in Azerbaijan. Not so, said Aliyev. There are no political prisoners in Azerbaijan. The people who came up with these statistics were lying. There was a programme of “deliberate provocation” against Azerbaijan — though it was unspecified who was leading this programme.

Aliyev swore that this plot to undermine Azerbaijan would fail.

The Azerbaijani president is not alone in his capability for bare-faced falsehood. It’s a specific strain of Soviet and post-Soviet behaviour, learned from the Communist Party and the KGB. If the leader says something, it is true, no matter what the evidence to the contrary. There are no political prisoners in Azerbaijan, says Aliyev, and we encourage a free media because it is important to our democracy; Ukraine has been taken over by fascists, says Vladimir Putin, and Russia has no choice but to fight them. There is no point in putting on a play about depression in Belarus, an Alexander Lukashenko apparatchik tells the Belarus Free Theatre, because there is no such thing as depression in Belarus.

“So what?” you may say. “Politicians and institutions lie.” And you’d be right. But this is a form of lying that goes far beyond “I was perfectly within my rights to claim those expenses”/”I did not have sex with that woman”. Political lies in functioning democracies tend to have to do with cover ups of personal or institutional failings. In an authoritarian society, with power utterly concentrated to the leader and his cadre, there is no such thing as an isolated failure. As a result, every aspect of life must be spun. All triumphs belong to the leader, all criticisms are propaganda, all failures sabotage. When there is no balance of power, is there really an objective truth? When, for example, the dictator Lukashenko told a journalist that journalist Irina Khalip, under house arrest, could leave Belarus any time she wanted, was that actually true? Was it true the moment he said it? Did it become true after he said it? And did it remain true?

This state of things raises a question for those of us seeking to better the lot of people living under regimes such as Belarus and Azerbaijan: can we pounce on the moments when autocrats declare as fact something we know to be untrue, cling on until they actually make it true? Or does this merely confirm the idea that truth is whatever their whim makes it?

This article was posted on June 26, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Jun 14 | News and features, Russia, Ukraine

Wrestling for the rights to define the Ukrainian conflict, both Russia and Ukraine have utilised a range of tactics to control and limit media coverage in the region. This, alongside, the constant to and fro between media freedom and the skewed official lines has politicised the role of the media and manipulated perceptions of the conflict, further distancing coverage from reality.

Every fact is a battle to be fought and won. Who made up the Ukrainian protest movement? Activists and other members of civil society, or thugs, neo-Nazis or far-right extremists? What are Russia’s motivations? Geo-political revisionism, a nationalistic desire to rebuild empire or for the protection of a persecuted minority? There is not one answer to questions like these; indeed the answers appear to changes depending on where they come from.

A sure-fire tactic to control the number of answers on offer is to limit the number of journalists able to cover the story. There have been a number of cases across the region where journalists have either been detained or refused entry to key areas of the conflict. In May, it was reported that three journalists, including a writer for Russia Today, had been detained by Ukraine’s Security Services (SBU), with a further three refused entry at the border. With no clarification of the grounds for their detention, as well as refusing them access to legal representation, the legality of such acts is dubious at best; as Human Rights Watch (HRW) states: “Failure to provide information on the whereabouts and fate of anyone deprived of their liberty by agents of the state, or those acting with its acquiescence, may constitute an enforced disappearance.”

This however, is not a tactic employed exclusively by Ukraine. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Russian authorities and pro-Russian separatists detained five journalists in Crimea and mainland Ukraine. On 2 June in Donetsk, unidentified armed men in camouflage raided the offices of regional newspapers Donbass and Vecherny Donetsk, detaining senior editorial staff, and accusing the publications of “incorrect reporting”. It is reported that the captor’s demands included the stipulations that the editors, “change the papers’ editorial policy”.

This proved to be effective. The deputy editor of Donbass stated that both his paper and Vecherny Donetsk were “discussing the separatists’ demands and were considering shutting down the outlets for fear of future retaliation”.

Beyond limiting the freedom of journalists covering the conflict, state-led censorship and propaganda is creating media vacuums in key areas, promoting narrow and strictly controlled interpretations of the conflict.

Attacks on the media in Russia have ramped up significantly following Putin’s return to the presidency and have taken on a distinct urgency with the continuation of the Ukraine conflict. One example is the legislation pushed through the Duma banning the publication of negative information about the Russian government and military. This positions Russian activities in Ukraine at the heart of controlling perceptions of Russia in the media. Quoting the official explanatory note to the legislation, HRW reports: “’The event in Ukraine in late 2013-early 2014 evidenced…an information war’, and demonstrated the necessity to protect the younger generation from ‘forming a negative opinion of [their] Fatherland.’”

Another key piece of legislation at play in this context is the “Lugovoi Law”, which allows Roskomnadzor, the Russia state body for media oversight, to block online sources without any court approval. One publication that was blocked was Grani.Ru due in part to its criticism of the state’s handling of the Bolotnaya Square protests. Grani.Ru have unsuccessfully appealed the ruling, but Yulia Berezovskaya, director-general of Grani-Ru is not surprised.

Roskomnadzor has not lost a single case against the media. The Office of the Prosecutor General and Roskomnadzor refused to indicate the “offensive” materials that should have been removed from the website so that access could be restored.

Berezovskaya continues to see this as part of a larger shift in the state’s relationship to the media in the light of the Ukrainian crisis: “The Ukrainian crisis is a major part of Russian TV news while domestic issues are not covered.”

Rolling out robust limitations against opposition or independent media outlets in Russia, at times irrespective of the events in Ukraine, guarantees in a large part the allegiances of media bodies covering the crisis. Indeed with many voices absent from the debate, the state can be confident the official line is being towed, at times, irrespective of fact.

The manipulation of fact has come to define a large part of pro-Russia content. Moscow Times reports “when Vesti.Ru described clashes between pro-Russian and pro-Kiev protesters in Simferopol…it showed footage of earlier protests in Kiev, which were more violent.” Channel One, when alleging that violence in Ukraine has sent a flood of refugees heading for Russia’s Belgorod region, used footage, not of the Ukrainian-Russian border, but of the Ukrainian-Polish border.

By restricting who can report on the Ukrainian crisis through access or censorship, the state can identify which untruths should be accepted as “truth” and which truths should not be seen. But as the conflict endures, the battle to shape perceptions, both home and abroad will continue. As it does, how can we identify the true actions, motivations and responsibilities, before untruths take hold and become something more, something resembling and assumed to be fact?

This article was published on 25 June 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Jun 14 | News and features, Politics and Society

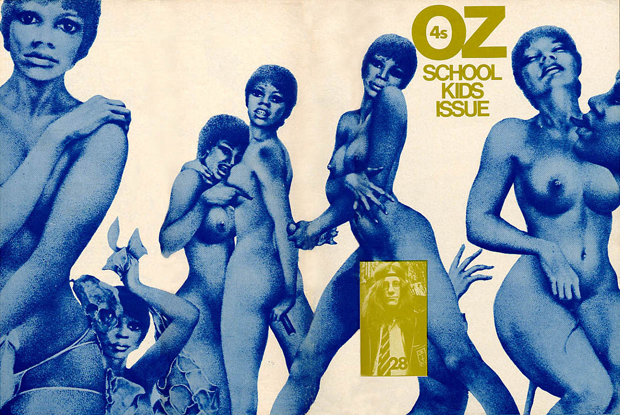

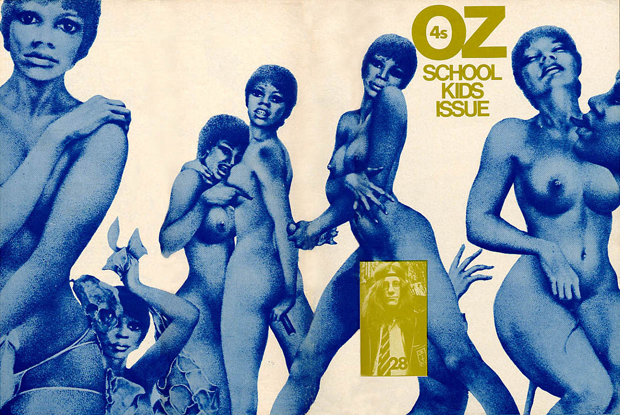

The school kids issue of Oz magazine lead to one of the longest conspiracy trials in England (Image: OZ/Wikimedia Commons)

Felix Dennis, a publisher, poet and spoken word performer, passed away on Sunday at his home in Stratford-upon-Avon, aged 67. Dennis was perhaps most well-known for being the brainchild behind publications such as Blender, Men’s Fitness, and The Week. But it was his work with Oz magazine as co-editor in the 1970s, and the ensuing conspiracy trial over the infamous school kids issue of the publication which first threw Dennis’ name into the limelight.

In 2008, John Mortimer spoke to Index about defending the editors of Oz magazine as he took on one of the most infamous obscenity cases on the 1970s:

Oz was a satirical, underground magazine founded in Australia in the 1960s. The editors of the London edition – Richard Neville, Jim Anderson and Felix Dennis – were prosecuted under the Obscene Publications Act in 1971 for a schoolkids issue (edited by teenage schoolchildren). Particular offence was caused by a cartoon of Rupert Bear having sex – in a collage created by schoolboy contributor Vivien Berger. The editors were found guilty and the convictions provoked an outcry. Hundreds demonstrated outside the Old Bailey in London, including John Lennon and Yoko Ono. The verdict was later quashed on appeal.

Index: What were the grounds for prosecution?

John Mortimer: Well, it was sort of the birth of that particular Obscene Publications Act [1959], which was Roy Jenkins’s doing [Jenkins was principal sponsor of the bill as a backbench MP]. It was meant to be liberalising, because it allowed defences of literary merit and scientific merit and all sorts of ‘bits’ of merit. It was a test of that and the Obscene Publications Act, which was meant to be a work of great liberality. It would test obscenity, which was something that would tend to deprave and corrupt the people who were likely to read it. But then there were numerous defences – that it was of literary merit or historical merit or scientific merit and so on. It seemed rather strange you could be depraved and corrupted, and on the other hand you knew more about history – that could be a defence. So it never ever seemed to me to be a particularly sensible piece of legislation.

Index: What did you think of it first of all, when you discovered what the charges were?

John Mortimer: It was the schoolkids Oz and nobody wanted to do it. Everybody turned it down. They thought it was disgraceful, defending the schoolkids Oz like that. Numerous QCs turned it down.

Read the full article here.

24 Jun 14 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

(Image: Al Jazeera English/YouTube)

In a heavy blow to press freedom in Egypt, three Al Jazeera English (AJE) journalists were convicted Monday on charges of spreading false news, aiding a terrorist organisation and endangering national security.

Australian award-winning journalist Peter Greste and Canadian-Egyptian national Mohamed Fahmy, AJE Cairo Bureau Chief, were handed down seven-year jail sentences each. A third AJE journalist, Baher Mohamed, was meanwhile, sentenced to ten years — three more than his colleagues, on an additional charge of possessing an empty bullet case. The three journalists have been in detention since December and have steadfastly denied the charges against them.

Ten defendants in the same case — including three foreign journalists — were sentenced to 10 years in absentia, while three others — including Anas El Beltagui, son of jailed Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohamed El Beltagui — were acquitted.

The rulings shocked and outraged journalists and rights activists around the world, fuelling concern about freedom of expression and the independence of the judiciary in Egypt, three years after the country witnessed a mass uprising that toppled the authoritarian regime of Hosni Mubarak, raising hopes of greater freedoms.The unexpectedly harsh verdicts also sent a chilling message to journalists working in Egypt that the government was adamant on pursuing its zero-tolerance approach to dissent and that journalists are not immune from the authorities’ policy of silencing critics at any cost.

Sherine Tadros, an Egyptian journalist and former AJE reporter denounced the verdict in a Twitter post shortly after it was pronounced, saying: “As a friend of the jailed journalists, I feel incredibly sad; as a journalist, I am scared and as an Egyptian, I’m ashamed.”

“The ruling sends a clear message to journalists to adhere to the official narrative or risk severe punishment,” an Egyptian broadcaster who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Index after the verdict.

Meanwhile, in an interview on Al Jazeera shortly after Monday’s court session, Amnesty International director Steve Crawshaw deplored what he called an “outrageous ruling”, adding that the verdict was another step in Egypt’s “campaign of terrorizing people and terrorizing the media”.

Since Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was deposed on 3 July, dozens of journalists have been detained in Egypt as part of a massive government crackdown on dissenters of all stripes: Muslim Brotherhood leaders and supporters, secular activists and journalists.The release this week of two journalists — including Abdulla El Shamy, a reporter for the Al Jazeera Arabic Channel who had been held in detention since mid August — had raised hopes that at least 14 other journalists still in detention, would also be acquitted. The judge’s decision to prolong the detention of the AJE journalists however, has raised questions about the new government’s commitment to democratic principles.

“Today’s verdict is deeply disappointing. The Egyptian people have over the past three years, expressed their wish for Egypt to be a democracy. Without freedom of the press there is no foundation for democracy,” Britain’s ambassador to Egypt, James Watt, told Reuters after the verdict.

In the past eleven months, journalists covering “anti-coup” protests staged by Muslim Brotherhood supporters have allegedly been deliberately targeted by security forces and pro-government mobs who accuse them of being “paid agents” and “spies”. Since the Islamist president’s ouster last July, five journalists have been shot dead and several others wounded by riot police while reporting on the clashes between protesters and security forces, prompting an outcry from rights groups. In a statement released in April, the Cairo-based Arab Network for Human Rights Information denounced the increased attacks on journalists and called on the Press Syndicate and media outlets to ensure their protection. The New York-based Committee for the Protection of Journalists which ranked Egypt among the three “most deadly” countries for journalists in a 2013 report, also called on the Egyptian government to investigate the assaults on journalists and hold the perpetrators of such crimes to account. The calls came in response to the death of Mayada Ashraf, a 22 year old reporter who worked for the privately-owned Al Dostour newspaper. She became Egypt’s latest journalist-fatality when she was shot in the head on 28 March while covering the dispersal of a Muslim Brotherhood protest in Cairo.

Several Egyptian journalists have in recent months, complained of intimidation. They said they had received threats from security agents or were subjected to smear campaigns aimed at tarnishing their reputation. In today’s repressive, deeply polarised climate in Egypt, many local journalists have decided to “play it safe” adopting the state narrative and persistently vilifying the Muslim Brotherhood while lionising the military and the new president.

Not surprisingly, there has been little sympathy for the jailed AJE journalists in the Egyptian press. Out of fear of being labelled “unpatriotic” by the public or suffering an even worse fate, most local journalists have either remained silent on the AJE case or taken a stand against the defendants, referring to them as part of a “Marriott Cell” and implying they were “traitors” who had been working to sabotage the country. Some of the guests interviewed by talk show hosts on state-influenced media channels recently, have echoed the prosecution’s argument that “channels like Al Jazeera brought down Iraq and were planning to do the same in Egypt”. In the wake of Monday’s court rulings, it is highly likely that the current trend of journalists practicing self-censorship will continue.

After Monday’s verdict, Egyptian State Television reported that Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry had forcefully rejected pressure from foreign governments to overturn the court decision. On a visit to Cairo the day before, US Secretary of State John Kerry had reportedly raised the issue of media freedom in talks with the country’s new President Abdel Fattah El Sisi. Kerry who had expressed concern about the jailing of journalists in Egypt, reacted to the verdict Monday by calling it “chilling and draconian”.

Meanwhile, rights activists also expressed alarm at the outcome of Monday’s court proceedings, calling the trial “political”.

“The charges against the journalists are politicised,” said Mohamed Lotfy, a rights activist who has worked as a researcher with Amnesty International. “The AJE journalists are pawns, caught in the middle of a political dispute between Qatar and Egypt.”

The Egyptian authorities are angry over Qatar’s continued support for the Muslim Brotherhood, delcared by Egypt a “terrorist organisation” last December. The Egyptian government has also accused the Qatari-funded Al Jazeera network of bias in favour of the outlawed group — an accusation that has been repeatedly denied by the network.

While most activists are “appalled” by Monday’s verdicts and have laid the blame on what they call a “highly politicised judiciary”, Sahar Aziz, an Associate Professor of Law, Texas A&M University, told Index she believes judges in Egypt are themselves “victims” of the country’s turbulent political transition.

“There is evidence that some judges are under indirect pressure from the executive branch to adjudicate these political cases in ways that legitimise the official narrative that the state is facing a threat to its national security,” she said, adding that “Over the past year, a group of judges reputed to be independent have been expelled from the judiciary through ‘voluntary retirement’ or in other settlements with the governing judiciary apparatus. This has sent a chilling message to other judges that the cost of truly independent adjudication is prohibitively high.”

But the government’s piling pressure on the judges meant little to family members of the jailed journalists who were stunned by the ruling.

“It is shocking. We were totally unprepared for this,” said Andrew Greste, Peter’s brother who had expected Peter to fly back to Australia with him where his elderly parents were eagerly awaiting their son’s return. “Obviously, it will take some time to rethink our plans and decide what we can do next,” he told journalists outside the courtroom.

Mohamed Fahmy’s fiancee Marwa, who attended the court session, broke down crying on hearing the verdict. The couple had been planning their wedding in April.

Wafaa Bassiouny, Fahmy’s mother, shouted out as she walked out of the courtroom, “What has my son done to deserve this? He was just doing his job. He is now unable to move his right arm, isn’t that enough?”

Fahmy has been denied adequate medical treatment by prison authorities for a shoulder injury sustained before his arrest and has now lost full use of his right arm

But all hope is not lost. It is still highly likely that through an appeals process, the sentence may be reduced, or the journalists may even be acquitted at a later date. Only by recognising justice and reversing its current course, can the new government in Egypt gain credibility in the eyes of the international community and win the backing and solidarity it badly needs.

This article was posted on 24 June, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Jun 14 | News and features, Politics and Society

Index speaks at the IAPC meet 2014, Vienna

There has been an 18% rise in violence towards journalists compared to the same period last year, International Media Support, an organisation that works in many of the world’s biggest danger zones, told an international journalism conference.

News from Egypt – as three journalists from Al-Jazeera are sentenced to seven years in prison – demonstrates the huge threats that journalists can face. The subject was covered in detail at this year’s International Association of Press Clubs annual conference in Vienna, which Index on Censorship attended this month.

“Some countries we just can’t work in,” said John Barker from Media Legal Defence Initiative, who help represent journalists facing legal charges for reporting and presented on their work. “Every time we work in Vietnam, for example, the lawyers are arrested. In many places, we can’t transfer money to them.” Nonetheless, they are currently working on 102 cases in 39 countries.

Other topics for discussion included:

- The increasing number of freelancers working in danger zones – and with little training

- How to protect fixers, translators and local journalists

- Possible methods for funding legal representation (Crowdfunding worked as a recent experiment in Ethiopia, said MLDI)

The event was hosted by Austria’s PresseClub Concordia – said to be the oldest press club in the world (founded in 1859 – reformed in 1946, after having its assets seized by Nazis). It was attended by press clubs from around the world, including Poland, Belarus, Syria, the Czech Republic, the US, India, Ukraine, Mongolia, Germany, and Switzerland. Other NGOs – alongside Index, International Media Support and Media Legal Defence Initiative – included the International Press Institute and RISC (Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues).

Index was invited to present on the work the organisation is doing around the world, which included sharing the stories of our Freedom of Expression Awards winners and nominees, and news of our current work, including a crowdsourcing project to map media freedom violations across the EU. Plus we also shared stories from our quarterly magazine – including a report on violent threats to journalists in Tanzania and how news stories are getting out of Syria via citizen reports.

Index also hosted round-table discussion on censorship, which provoked an impassioned debate. One of the most interesting topics covered was on contracts that some journalists are being made to sign on what they can and can’t write. We heard of cases in Mongolia and Germany. We also discussed self-censorship and censorship by complying to advertisers’ will. One attendee from the Berlin Press Club said: “There is no censorship in Germany, but journalists feel like they have scissors in their heads. You have to self-censor before you write.” This is an area that we are researching, so please get in touch if you have experiences and examples.

The meeting also visited a new exhibition on censorship during WW1 and ended with the Concordia Press Club’s annual ball, which is a key fundraiser for the club and attended by over 2,000 guests. See photos from the event below.

This article was posted on June 24, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Jun 14 | Egypt, News and features, United Kingdom

(Photo: Casey Prottas for Index on Censorship)

The usually bustling entrance of the New Broadcasting House in London was still filled to the brim with people this morning, but for one minute they were completely silent.

BBC staff, joined by fellow journalists from around the world, stood in silent protest at 9:41 am, exactly 24 hours from the sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists to prison in Egypt. Peter Greste and Mohamed Fahmy were each handed down seven-year sentences, while Baher Mohamed was given ten years.

The three journalists were found guilty on Monday for spreading false news by a court in Cairo. Ten other journalists, including Al Jazeera’s Sue Turton and Dominic Kane, and Rena Netjes, a correspondent for Dutch newspaper Parool, were also sentenced in absentia to ten years.

The silent protest was orchestrated in hopes of fighting against these unjust practices and to raise awareness of the dangers and censorship many international journalists face.

BBC Director of News, James Harding, stood up and addressed the group: “They are not just robbing three innocent men of their freedom, but intimidating journalists and inhibiting free speech.”

The protestors held signs that read #FreeJournalism and #FreeAJStaff, and covered their mouths with tape in order to illustrate their frustration with the trial verdict.

Sana Safi, a presenter for BBC Pashto TV News, said: “When I heard the verdict, I was in shock because I’m from Afghanistan and we have seen more media freedom in the last few years, and I wasn’t expecting anything like that from a country like Egypt.”

Their looks were determined and their heads were held high as cameras flashed and captured the intense moment. Cowardice was not an option.

Nasidi Yahaya, a social media producer from BBC Hausa, said: “The verdict was so unfair, these guys were just doing their job. Journalists should not be silenced like this.”

The journalists from the BBC, Al Jazeera, and other news organisations standing together in solidarity will also be sending a letter calling on the Egyptian president to intervene in the situation.

The wait for their freedom begins.

This article was posted on 24 June, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jun 14 | Egypt, News and features

The sentencing of Al Jazeera journalists today took Michelle Betz back to her own trial.

Just over a year ago I was awoken around 5am in Washington by a call from my Egyptian colleague. “Guilty,” he breathed. “We are all guilty”. I could hear the shock in his voice. I couldn’t yet feel my own shock.

We were defendants in the NGO trial in which 43 people working for four US and one German NGOs were accused of charges including operating without a licence and bringing foreign funds into the country. There were so many ironies about the case, the trial, and the charges; so many outrages; so many injustices. There were many, many parallels with what is happening now with the Al Jazeera journalists.

There was little international noise around our “trial”. And that is the one thing that has been different with the Al Jazeera trial – at least there has been no silence.

At the time I was working with the International Center for Journalists, from Washington DC. Judicial officials didn’t even have my full name, but there I was number 39 on the charge document.

I knew full well one year ago that we would be found guilty despite the multitude of assurances from all corners: the NGOs, the US State Department, the lawyers – all tried to assure us that this was all political (between the US and Egypt) and that this would “all go away”. Of course, logically, this should have all gone away. Just as with the Al Jazeera case, logically, it never should have happened. Logically, we, as they, should have been found innocent.

But dealing with the Egyptian judicial system is anything but logical.

In neither case was there any evidence and in neither trial did the prosecution have any legitimate case. But that was beside the point. They didn’t need evidence. They didn’t need a case. All they needed to do was follow the directive from on high and read the verdict: guilty.

I lived in Egypt for three years and I can never go back. If I did I would be immediately imprisoned.

Some have expressed surprise at the speed with which today’s verdict was rendered asking how the judge could possibly have written his judgment in so short a time. He didn’t. Instead, it’s highly likely that the judgment was already written six months ago. The judge was simply doing what he was told. I too would have worn sunglasses to court today; I too would have dragged my feet getting to work for surely there was some weight on his conscience.

So what now? The Egyptians learned from our case. At least in the NGO case none of us were imprisoned, though Egypt did pursue some of us through Interpol. The one thing the US did was to get all Americans (save one hero, Robert Becker, who refused to leave his Egyptian colleagues facing trial alone) first to the US Embassy in Cairo (where they stayed for days) and then finally flew them out in the middle of the night after some backroom deal was worked out with Egyptian officials.

And the Egyptian establishment has learned from this. They learned not to allow bail to prevent defendants leaving Egypt. They learned that the US (and the international community at large) didn’t care and that there would be no repercussions even if American citizens were convicted and sentenced to five years of hard labor. They learned that even the media didn’t care.

But on that last point they miscalculated – they didn’t realise that there is a tribe of journalism, which does not suffer injustice and attacks on its own. And that is our hope at this point – that we raise our voices, we continue to speak the truth, we continue to point to injustices, including injustices wrought on our tribe. For if we are silenced, then we all face injustice.

Yes, of course there was no evidence and of course the prosecution had no case. And so today we find ourselves one year on watching in horror as three Al Jazeera journalists are convicted and sentenced to 7-10 year prison sentences and those convicted in absentia to an even lengthier sentence (just like those convicted in absentia in the NGO trial, such as myself, who received longer sentences).

And so while my colleagues were shocked by our verdict one year ago, I was not. And if we were found guilty then so too would our Al Jazeera colleagues. There was a message to be sent.

But the convictions should be no surprise. Rule of law in Egypt as always been tough to find but almost any remaining semblance of it disappeared with the coup of 2013.

This article was posted on June 23, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jun 14 | Belarus, News and features

Ales Bialiatski was released from detention. (Photo: Andrei Aliaksandrau for Index on Censorship)

Ales Bialiatski, a Belarusian human rights defender, was released from prison on Saturday after almost three years behind bars on politically motivated charges.

“My release came as a surprise. I was not expecting anything like that. There was a usual routine check in the morning and they took me to work with other prisoners. But around 9 a.m. I was summoned to the prison director’s office, where they told me I am being released due to an amnesty,” Bialiatski said during the press conference in Minsk today.

Bialiatski, the chair of the Human Rights Centre Viasna and a vice president of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), was arrested on 11 August 2011 in Minsk and later sentenced to 4.5 years in prison for alleged tax evasion. He did not admit guilt and stated the funds in his bank accounts abroad were in fact spent for activities of Viasna and supporting victims of human rights abuses in Belarus.

“I am not sorry for those three years I spent in prison. This is the price you pay for making Belarus a free and democratic country. If we want to improve our life and drag Belarus out of the swamp it has been in for 20 years already, we need to be active and not to be afraid of repressions civil society faces. I knew what I was in prison for, that is why it was easy for me emotionally,” Bialiatski said.

In fact, it was not always easy. “Political prisoners in Belarusian jails are kept in different conditions than other prisoners. For instance, no one was allowed to talk to me, even if it was a friendly chat about weather or football, a person who approached me could be punished by the prison authorities. That was just one of many examples of physiological pressure political prisoners face in jail,” he said, describing his time behind bars.

He symbolically crossed his name out of the list of Belarusian political prisoners on a campaigning T-shirt his colleagues wore while he was in jail.

“So, Bialiatski is out, but seven more are still there. Belarus has to become a country without political prisoners. I demand from the authorities to release all political prisoners and stop prosecuting people for their political views,” Bialiatski said.

Bialiatski expressed his gratitude to “tens of thousands of people” from Belarus and around the world who supported him during his time in prison and campaigned for his release. Bialiatski also said he is not going to leave the country and he is determined to continue his human rights work.

There will certainly be ground for that as Belarus continues to have a poor human rights record. Most commentators inside the country do not see Bialiatski’s release as a sign of any genuine improvement of the human rights situation, but merely a step of “good will” that can ensure possible renewal of a dialogue with the European Union.

“The EU is clearly looking for ways and platforms for a dialogue with Belarus. Europe certainly wants to decrease tensions in the region and stabilize the situation that was created because of Ukraine and its conflict with Russia. And it can be strategically important for the EU not to allow Belarus turn completely pro-Russian. The problem is the authorities of the country refuse to talk to the Belarusian civil society, and what we have started seeing is the West is ready to give in to the government of Belarus and ‘sacrifice’ participation of active NGOs in a possible dialogue. This will be a huge mistake. Lukashenko is going to deceive Europe once again, and we can see another clampdown on civil society of the country after the presidential elections of 2015,” Uladzimir Matskevich, a Belarusian methodologist and analyst, says.

“I am really happy Ales is out of prison – but I can hardly say he is ‘free’. We are all not free here. Bialiatski’s release is certainly great, but it does not signal any change. The authorities keep tight control over society. Dictators act this way; they need to show they are capable of strict punishment and mercy; they need to show acts of both time to time to manifest they are in charge. This is perhaps what we see with Ales’ release. The opposition is still too weak and disengaged to break through this vicious circle,” Matskevich said.

This article was published on June 23, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jun 14 | Egypt, News and features

Index on Censorship condemns the sentencing of three Al Jazeera journalists in Egypt to seven years each in prison. Peter Greste, Mohammed Fahmy and Baher Mohamed were sentenced today to seven years imprisonment under accusations of spreading false news and supporting the Muslim Brotherhood. The journalists were detained on 29 December 2013.

“Today’s verdict is disgraceful,” Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg said. “It tells journalists that simply doing their job is considered a criminal activity in Egypt. We call on the international community to join us in condemning this verdict and ask governments to apply political and financial pressure on a country that is rapidly unwinding recently won freedoms, including freedom of the press. The government of newly elected president Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi must build on the country’s democratic aspirations and halt curbs on the media and the silencing of voices of dissent.”

The court’s decision comes as a severe setback for all journalists currently jailed or prosecuted for doing their job, and reinforces claims of a politicised judiciary in Egypt. Other defendants in the case, who were tried in absentia, got sentenced to 10 years.

Index is deeply concerned at the growing number of imprisoned journalists in Egypt and around the world. At least 14 journalists remain in detention in Egypt and some 200 journalists are in jail across the globe. Many of those arrested in Egypt were reporting on protests following the ousting of Mohamed Morsi or the passing of a controversial anti-protest law.

We reiterate our support to journalists to report freely and safely and call on Egyptian authorities to drop charges against journalists and ensure they are set free from jail. And we ask governments to maintain pressure on Egypt to ensure freedom of expression and other fundamental human rights are protected. Index joined the global #FreeAJStaff campaign along with other human rights, press freedom groups and journalists.

20 Jun 14 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Russia

@AndreiSoldatov and @cyberrights at the @IndexCensorship Brussels event on Press Freedom in Russia Turkey Azerbaijan. Photo: Ricardo Gutiérrez

On Thursday, Index hosted a discussion with five leading media experts from Turkey, Russia, and Azerbaijan. As journalists, bloggers, entrepreneurs and campaigners, they experience first-hand how censorship – online and off – is being ramped up in their countries, and they argue that their stories are still not being sufficiently heard.

Turkey’s Yaman Akdeniz and Amberin Zaman, Russia’s Andrei Soldatov and Anton Nossik, and Azeri blogger Arzu Geybulla shared shocking stories about journalists harassed in government-led smear campaigns, the arrests on spurious criminal charges of those who speak openly on social media, and the growing role of governments in blocking free expression online.

“The internet is becoming less and less independent of government interference,” Nossik told the Brussels audience.

Index works with writers – including authors, journalists and bloggers – and artists globally to help them tell a wider world about the threats they face. We are a platform that allows individuals to speak for themselves, and fights for those who cannot.

In the first article from one of our event speakers, Andrei Soldatov assesses the state of online freedom in Russia:

Since November 2012, we’ve been living in a country with the internet censored extensively by a nationwide system of filtering.

This system has been constantly updated ever since. Now we have four official blacklists of banned websites and pages: the first one is to deal with sites deemed extremist; the second is about sites blocked because of child pornography, suicide and drugs; the third consists of sites with copyright problems; the fourth, the most recent one, was created in February and lists the sites blocked without a court order because they call for non-sanctioned protests. There is also an unofficial fifth blacklist aimed not at sites but at hosting companies, based abroad, which have proven themselves not very cooperative with Russian authorities.

Technically, the internet filtering system in Russia is not very sophisticated. Thousands of sites were blocked by mistake, while if you want to access a blocked site you can do that using circumvention tools or even very basic things like Google translate.

At the same time very few people were sent to jail for posting critical things online, and relatively few new media were put under direct government pressure.

But surprisingly, freedom of expression on the internet in Russia has been hugely affected: users have become cautious in their comments, and internet companies, the largest in the country, even when invited to talk to Putin, are so frightened that they failed to raise the issue of regulation at the meeting.

The beauty of the Russian approach is that it doesn’t need to be technically sophisticated to be efficient. It also doesn’t need mass repression against journalists or activists.

So why is that?

Basically, the Russian approach is all about instigating self-censorship. To do this, you need to draft the legislation as broad as possible, to have the restrictions constantly expanded — like the recent law which requires bloggers with more than 3.000 followers to be registered — and companies, internet service providers, NGOs and media will rush to you to be consulted and told what’s allowed. You should also show that you don’t hesitate to block entire services like YouTube – and companies will come to you suggesting technical solutions, as happened with DPI (deep packet inspection). It helps the government to shift the task of developing a technical solution to business, as well as costs.

You also need to encourage pro-government activists to attack the most vocal critics, to launch websites with list of so-called national traitors, and then to have Vladimir Putin himself to use this very term in a speech.

All that sends a very strong message. And as a result, journalists will be fired for critical reporting from Ukraine by media owners, not by the government; the largest internet companies will seek private meetings with Putin, and users of social networks will become more cautious in their comments.

We have seen this before – the very same approach was used against traditional media in the 2000s. What made the situation on the internet special is that the government found a way to shift the task of providing a technical solution for censorship to companies, including the global ones, and make the companies pay for the system. The way global platforms seem to respond to that is not very impressive. Localisation cannot be a solution because it helps to localise the problems of censorship. Now the Russian search engine Yandex presents two different maps of Ukraine, with and without Crimea, for the Ukrainian and Russian audiences respectively.

The biggest problem with this approach is that it provokes governments to put more pressure on global platforms. One day Twitter was heavily criticised by a Russian official in a pro-Kremlin paper who threatened to block the platform completely. The next day Twitter rushed to block an account of Pravy Sector, one of the most-anti Russian political parties in Ukraine, and blocked it for Russian users.

This article was published on June 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Jun 14 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, European Union, Events, Russia, Turkey