19 Jul 18 | News and features, Volume 46.01 Spring 2017

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

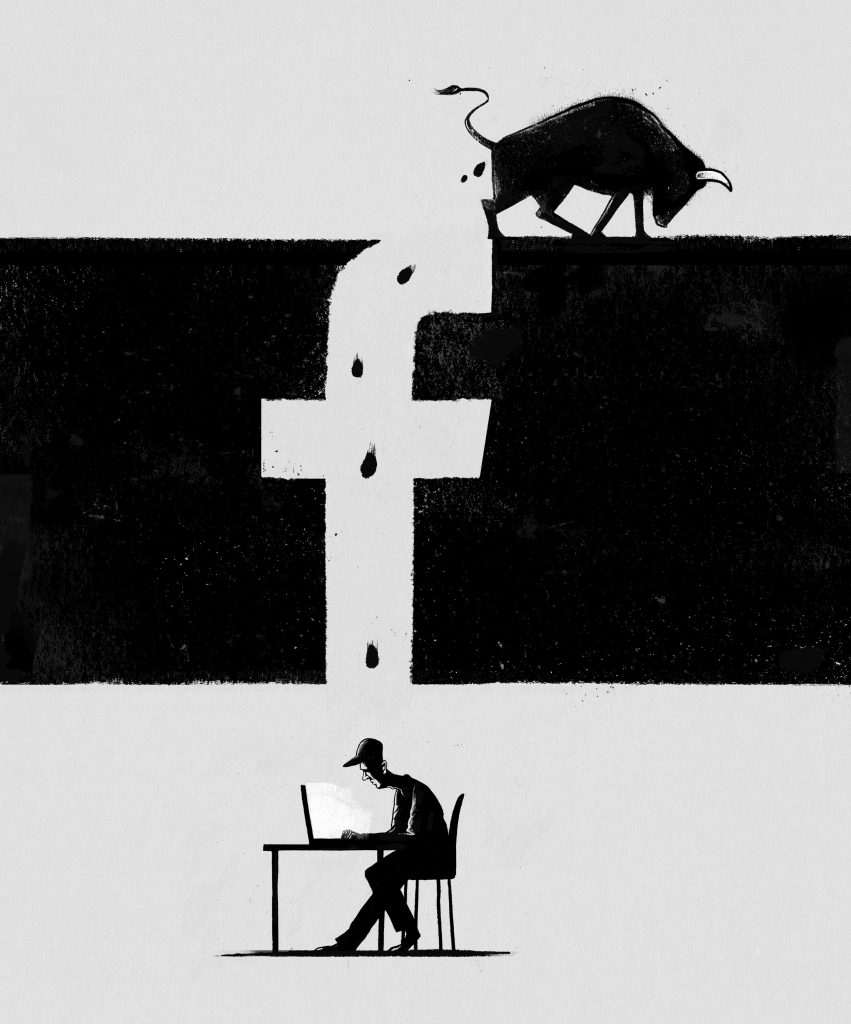

FICTIONAL ANGLES, SPIN, propaganda and attempts to discredit the media, there’s nothing new there. Scroll back to World War I and you’ll find propaganda cartoons satirising both sides who were facing each other in the trenches, and trying to pump up public support for the war effort. If US President Donald Trump is worried about the “unbalanced” satirical approach he is receiving from the comedy show Saturday Night Live, he should know he is following in the footsteps of Napoleon who worried about James Gillray’s caricatures of him as very short, while the vertically challenged French President Nicolas Sarkozy feared the pen of Le Monde’s cartoonist Plantu.

When Trump cries “fake news” at coverage he doesn’t like, he is adopting the tactics of Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa. Cor-rea repeatedly called the media “his greatest enemy” and attacked journalists personally, to secure the media coverage he wanted.

As Piers Robinson, professor of political journalism at Sheffield University, said: “What we have with fake news, distorted information, manipulation communication or propaganda, whatever you want to call it, is nothing new.”

Our approach to it, and the online tools we now have, are newer however, meaning we now have new ways to dig out angles that are spun, include lies or only half the story.

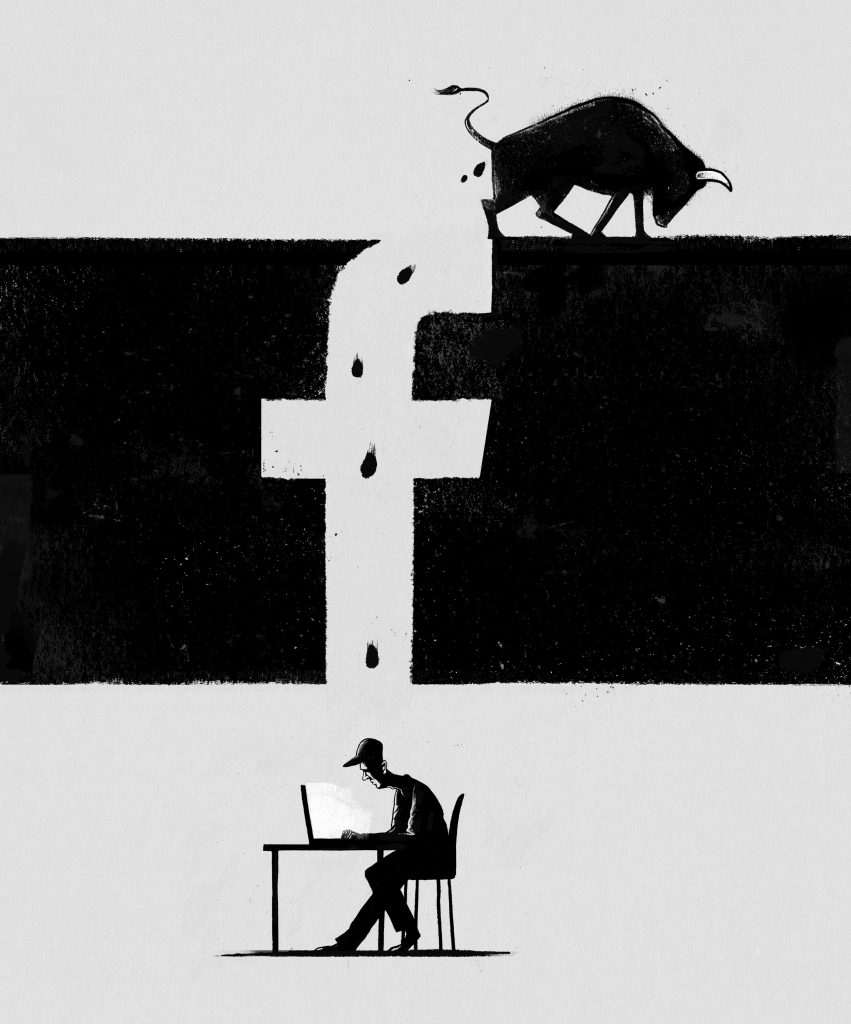

But sadly while the internet has brought us easy access to multitudes of sources, and the ability to watch news globally, it also appears to make us lazier as we glide past hundreds of stories on Twitter, Facebook and the digital world. We rarely stop to analyse why one might be better researched than another, whose journalism might stand up or has the whiff of reality about it.

As hungry consumers of the news we need to dial up our scepticism. Disappointingly, research from Stanford University across 12 US states found millennials were not sceptical about news, and less likely to be able to differentiate between a strong news source and a weak one. The report’s authors were shocked at how unprepared students were in questioning an article’s “facts” or the likely bias of a website.

And, according to Pew Research, 66% of US Facebook users say they use it as a news source, with only around a quarter clicking through on a link to read the whole story. Hardly a basis for making any decision.

At the same time, we are seeing the rise of techniques to target particular demographics with political advertising that looks like journalism. We need to arm ourselves with tools to unpick this new world of information.

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Turkey

A Picture Sparks a Thousand Stories

KAYA GENÇ dissects the use of shocking images and asks why the Turkish media didn’t check them

Two days after last year’s failed coup attempt in Turkey, one of the leading newspapers in the country, Sozcu, published an article with two shocking images purportedly showing anti-coup protesters cutting the throat of a soldier involved in the coup. “In the early hours of this morning the situation at the Bosphorus Bridge, which had been at the hands of coup plotters until last night, came to an end,” the piece read. “The soldiers handed over their guns and surrendered. Meanwhile, images of one of the soldiers whose throat was cut spread over social media like an avalanche, and those who saw the image of the dead soldier suffered shock,” it said.

These powerful images of a murdered uniformed youth proved influential for both sides of the political divide in Turkey: the ultra-conservative Akit newspaper was positive in its reporting of the lynching, celebrating the killing. The secularist OdaTV, meanwhile, made it clear that it was an appalling event and it was publishing the pictures as a means of protest.

Neither publication credited the images they had published in their extremely popular articles, which is unusual for a respectable publication. A careful reader could easily spot the lack of sources in the pieces too; there was no eyewitness account of the purported killing, nor was anyone interviewed about the event. In fact, the piece was written anonymously.

These signs suggested to the sceptical reader that the news probably came from someone who did not leave their desk to write the story, choosing instead to disseminate images they came across on social media and to not do their due diligence in terms of verifying the facts.

On 17 July, Istanbul’s medical jurisprudence announced that, among the 99 dead bodies delivered to the morgue in Istanbul, there was no beheaded person. The office of Istanbul’s chief prosecutor also denied the news, and it was declared that the news was fake.

A day later, Sozcu ran a lengthy commentary about how it prepared the article. Editors accepted that their article was based on rumours and images spread on social media. Numerous other websites had run the same news, their defence ran, so the responsibility for the fake news rested with all Turkish media. This made sense. Most of the pictures purportedly showing lynched soldiers were said to come from the Syrian civil war, though this too is unverifiable. Major newspapers used them, for different political purposes, to celebrate or condemn the treatment of putschist soldiers.

More worryingly, the story showed how false images can be used by both sides of Turkey’s political divide to manipulate public opinion: sometimes lies can serve both progressives and conservatives.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: China

A Case of Mistaken Philanthropy

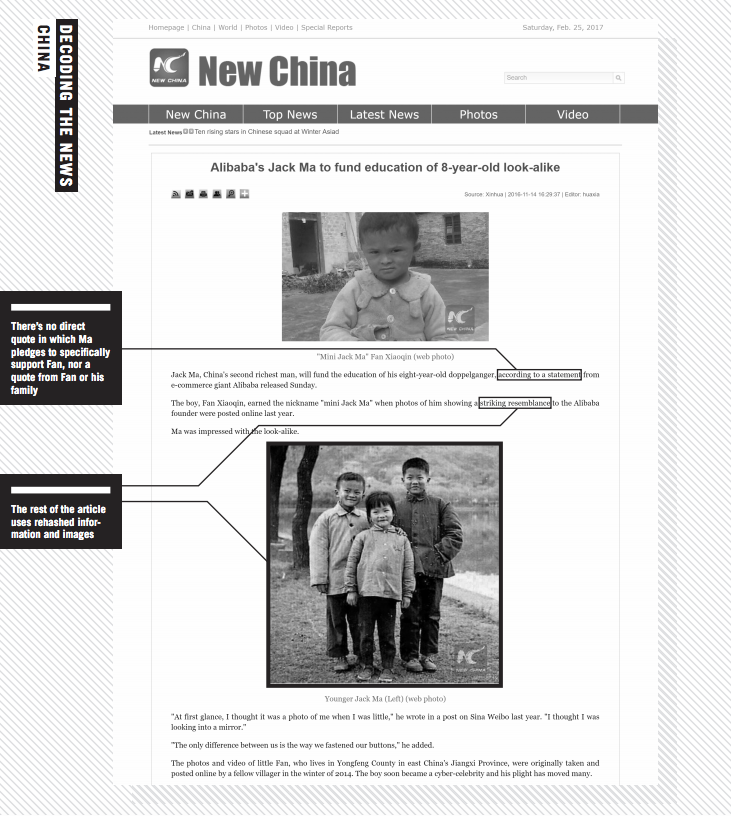

JEMIMAH STEINFELD writes on the story of Jack Ma’s doppelganger that went too far

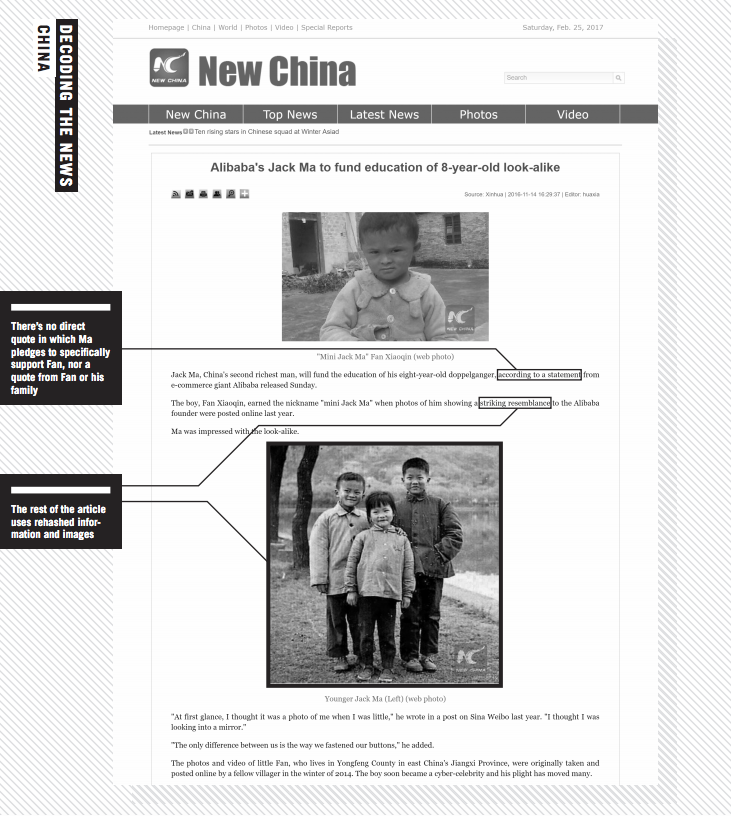

Jack Ma is China’s version of Mark Zuckerberg. The founder and executive chairman of successful e-commerce sites under the Alibaba Group, he’s one of the wealthiest men in China. Articles about him and Alibaba are frequent. It’s within this context that an incorrect story on Ma was taken as verbatim and spread widely.

The story, published in November 2016 across multiple sites at the same time, alleged that Ma would fund the education of eight-year-old Fan Xiaoquin, nicknamed “mini Ma” because of an uncanny resemblance to Ma when he was of a similar age. Fan gained notoriety earlier that year because of this. Then, as people remarked on the resemblance, they also remarked on the boy’s unfavourable circumstances – he was incredibly poor and had ill parents. The story took a twist in November, when media, including mainstream media, reported that Ma had pledged to fund Fan’s education.

Hints that the story was untrue were obvious from the outset. While superficially supporting his lookalike sounds like a nice gesture, it’s a small one for such a wealthy man. People asked why he wouldn’t support more children of a similar background (Fan has a brother, in fact). One person wrote on Weibo: “If the child does not look like Ma, then his tragic life will continue.”

Despite the story drawing criticism along these lines, no one actually questioned the authenticity of the story itself. It wouldn’t have taken long to realise it was baseless. The most obvious sign was the omission of any quote from Ma or from Alibaba Group. Most publications that ran the story listed no quotes at all. One of the few that did was news website New China – sponsored by state-run news agency Xinhua. Even then the quotes did not directly pertain to Ma funding Fan. New China also provided no link to where the comments came from.

Copying the comments into a search engine takes you to the source though – an article on major Chinese news site Sina, which contains a statement from Alibaba. In this statement, Alibaba remark on the poor condition of Fan and say they intend to address education amongst China’s poor. But nowhere do they pledge to directly fund Fan. In fact, the very thing Ma was criticised for – only funding one child instead of many – is what this article pledges not to do.

It was not just the absence of any comments from Ma or his team that was suspicious; it was also the absence of any comments from Fan and his family. Media that ran the story had not confirmed its veracity with Ma or with Fan. Given that few linked to the original statement, it appeared that not many had looked at that either.

In fact, once past the initial claims about Ma funding Fan, most articles on it either end there or rehash information that was published from the initial story about Ma’s doppelganger. As for the images, no new ones were used. These final points alone wouldn’t indicate that the story was fabricated, but they do further highlight the dearth of new information, before getting into the inaccuracy of the story’s lead.

Still, the story continued to spread, until someone from Ma’s press team went on the record and denied the news, or lack thereof.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: Mexico

Not a Laughing Matter

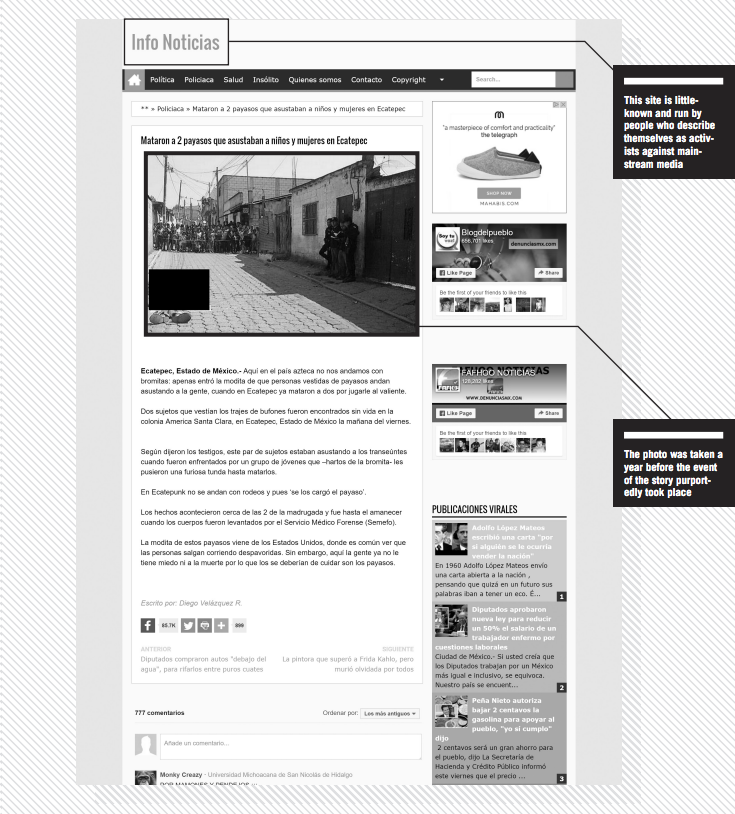

DUNCAN TUCKER digs out the clues that a story about clown killings in Mexico didn’t stand up

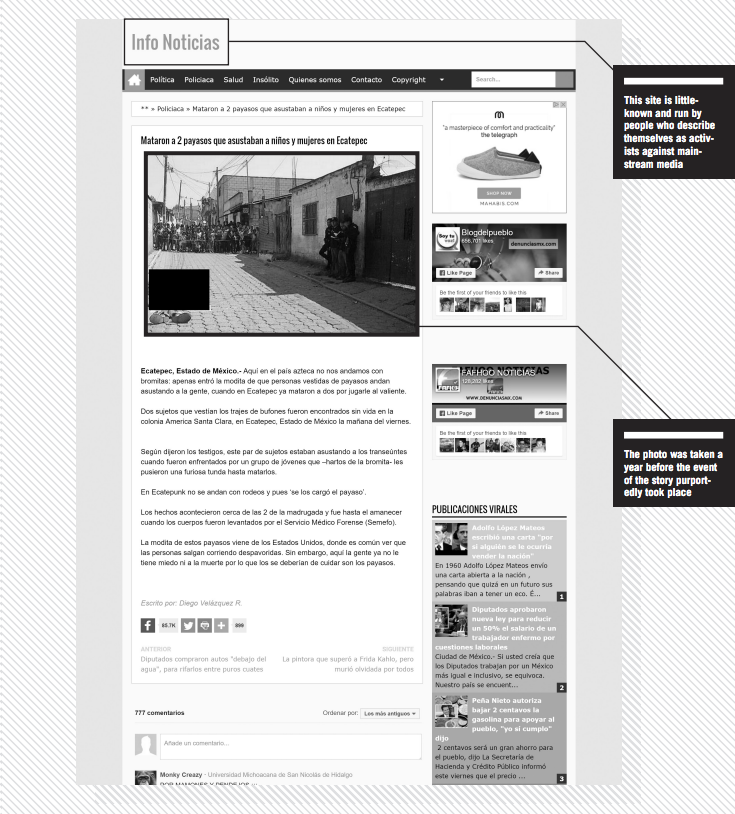

Disinformation thrives in times of public anxiety. Soon after a series of reports on sinister clowns scaring the public in the USA in 2016, a story appeared in the Mexican press about clowns being beaten to death.

At the height of the clown hysteria, the little-known Mexican news site DenunciasMX reported that a group of youths in Ecatepec, a gritty suburb of Mexico City, had beaten two clowns to death in retaliation for intimidating passers-by. The article featured a low-resolution image of the slain clowns on a run-down street, with a crowd of onlookers gathered behind police tape.

To the trained eye, there were several telltale signs that the news was not genuine.

While many readers do not take the time to investigate the source of stories that appear on their Facebook newsfeeds, a quick glance at DenunciasMX’s “Who are we?” page reveals that the site is co-run by social activists who are tired of being “tricked by the big media mafia”. Serious news sources rarely use such language, and the admission that stories are partially authored by activists rather than by professionally-trained journalists immediately raises questions about their veracity.

The initial report was widely shared on social media and quickly reproduced by other minor news sites but, tellingly, it was not reported in any of Mexico’s major newspapers – publications that are likely to have stricter criteria with regard to fact-checking.

Another sign that something was amiss was that the reports all used the vague phrase “according to witnesses”, yet none had any direct quotes from bystanders or the authorities

Yet another red flag was the fact that every news site used the same photograph, but the initial report did not provide attribution for the image. When in doubt, Google’s reverse image search is a useful tool for checking the veracity of news stories that rely on photographic evidence. Rightclicking on the photograph and selecting “Search Google for Image” enables users to sift through every site where the picture is featured and filter the results by date to find out where and when it first appeared online.

In this case, the results showed that the image of the dead clowns first appeared online in May 2015, more than a year before the story appeared in the Mexican press. It was originally credited to José Rosales, a reporter for the Guatemalan news site Prensa Libre. The accompanying story, also written by Rosales, stated that the two clowns were shot dead in the Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango.

While most of the fake Mexican reports did not have bylines and contained very little detail, Rosales’s report was much more specific, revealing the names, ages and origins of the victims, as well as the number of shell casings found at the crime scene. Instead of rehashing rumours or speculating why the clowns were targeted, the report simply stated that police were searching for the killers and were working to determine the motive.

As this case demonstrates, with a degree of scrutiny and the use of freely available tools, it is often easy to differentiate between genuine news and irresponsible clickbait.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

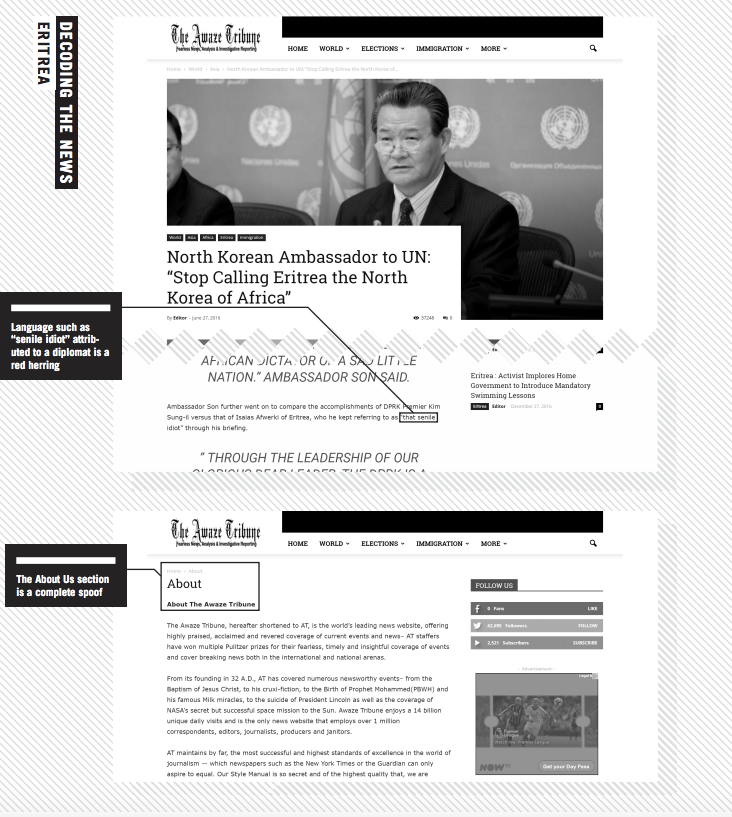

Decoding the News: Eritrea

Not North Korea

ABRAHAM T ZERE dissects the moment that Eritreans mistook saucy satire for real news

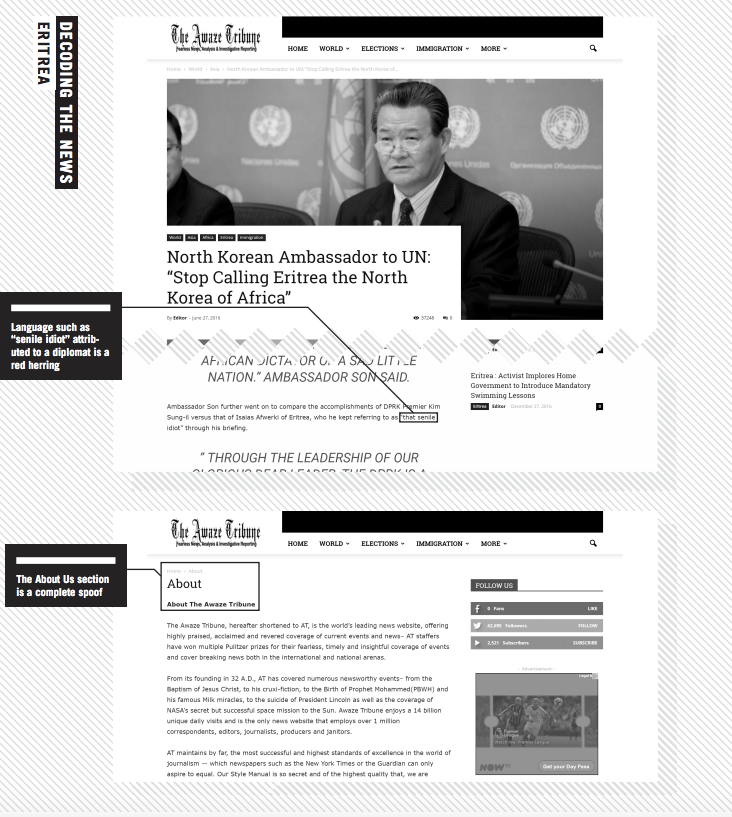

In recent years, the international media have dubbed Eritrea the “North Korea of Africa”, due to their striking similarities as closed, repressive states that are blocked to international media. But when a satirical website run by exiled Eritrean journalists cleverly manipulated the simile, the site stoked a social media buzz among the Eritrean diaspora.

Awaze Tribune launched last June with three news stories, including “North Korean ambassador to UN: ‘Stop calling Eritrea the North Korea of Africa’.”

The story reported that the North Korean ambassador, Sin Son-ho, had complained it was insulting for his advanced, prosperous, nuclear-armed nation to be compared to Eritrea, with its “senile idiot leader” who “hasn’t even been able to complete the Adi Halo dam”.

With apparent little concern over its authenticity, Eritreans in the diaspora began widely sharing the news story, sparking a flurry of discussion on social media and quickly accumulating 36,600 hits.

The opposition camp shared it widely to underline the dismal incompetence of the Eritrean government. The pro-government camp countered by alleging that Ethiopia must have been involved behind the scenes.

The satirical nature of the website should have seemed obvious. The name of the site begins with “Awaze”, a hot sauce common in Eritrean and Ethiopian cuisines. If readers were not alerted by the name, there were plenty of other pointers. For example, on the same day, two other “news” articles were posted: “Eritrea and South Sudan sign agreement to set an imaginary airline” and “Brexit vote signals Eritrea to go ahead with its long-planned referendum”.

Although the website used the correct name and picture of the North Korean ambassador to the UN, his use of “senile idiot” and other equally inappropriate phrases should have betrayed the gag.

Recently, Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki has been spending time at Adi Halo, a dam construction site about an hour’s drive from the capital, and he has opened a temporary office there. While this is widely known among Eritreans, it has not been covered internationally, so the fact that the story mentioned Adi Halo should also have raised questions of its authenticity with Eritreans. Instead, some readers were impressed by how closely the North Korean ambassador appeared to be following the development.

The website launched with no news items attributed to anyone other than “Editor”, and even a cursory inspection should have revealed it was bogus. The About Us section is a clear joke, saying lines such as the site being founded in 32AD.

Satire is uncommon in Eritrea and most reports are taken seriously. So when a satirical story from Kenya claimed that Eritrea had declared polygamy mandatory, demanding that men have two wives, Eritrea’s minister of information felt compelled to reply.

In recent years, Eritrea’s tightly closed system has, not surprisingly, led people to be far less critical of news than they should be. This and the widely felt abhorrence of the regime makes Eritrean online platforms ready consumers of such satirical news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

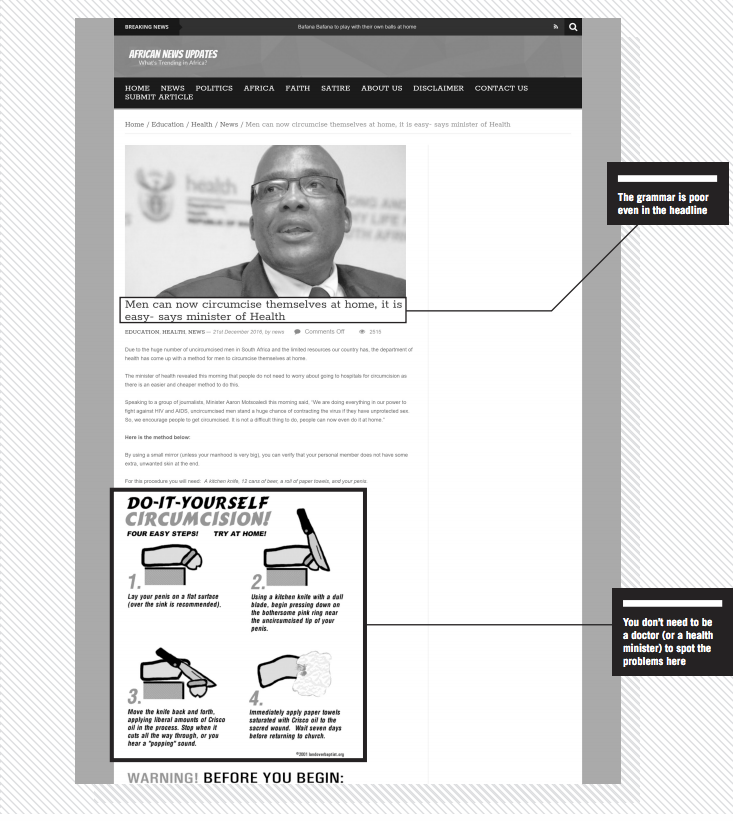

Decoding the News: South Africa

And That’s a Cut

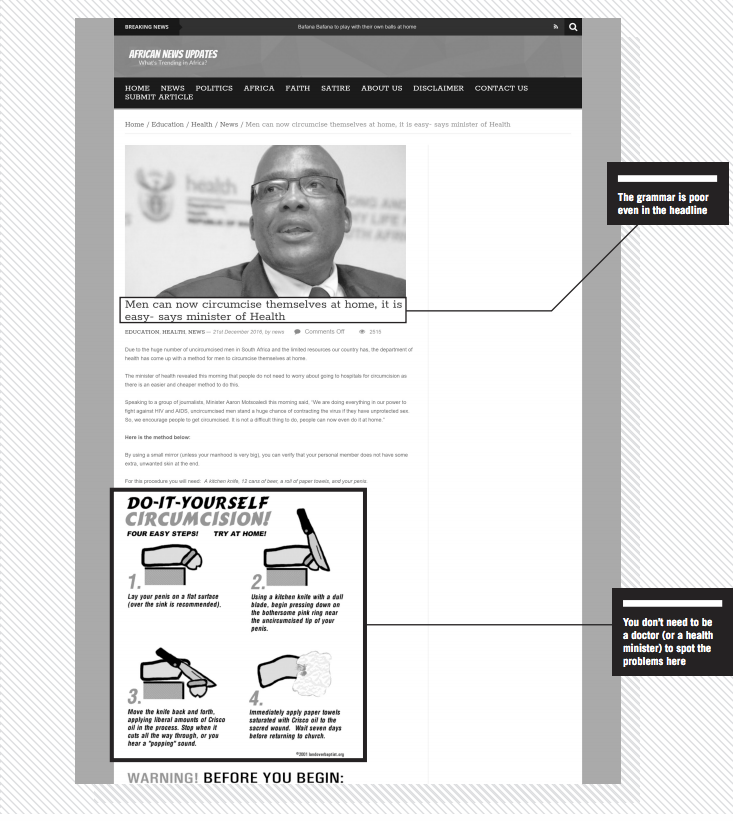

Journalist NATASHA JOSEPH spots the signs of fiction in a story about circumcision

The smartest tall tales contain at least a grain of truth. If they’re too outlandish, all but the most gullible reader will see through the deceit. Celebrity death stories are a good example. In South Africa, dodgy “news” sites routinely kill off local luminaries like Desmond Tutu. The cleric is 85 years old and has battled ill health for years, so fake reports about his death are widely circulated.

This “grain of truth” rule lies at the heart of why the following headline was perhaps believed. The headline was “Men can now circumcise themselves at home, it is easy – says minister of health”. Circumcision is a common practice among a number of African cultural groups. Medical circumcision is also on the rise. So it makes sense that South Africa’s minister of health would be publicly discussing the issue of circumcision.

The country has also recently unveiled “DIY HIV testing kits” that allow people to check for HIV in their own homes. This is common knowledge, so casual or less canny readers might conflate the two procedures.

The reality is that most of us are casual readers, snacking quickly on short pieces and not having the time to engage fully with stories. New levels of engagement are required in a world heaving with information.

The most important step you can take in navigating this terrible new world is to adopt a healthy scepticism towards everything. Yes, it sounds exhausting, but the best journalists will tell you that it saves a lot of time to approach information with caution. My scepticism manifests as what I call my “bullshit detector”. So how did my detector react to the “DIY circumcision” story?

It started ringing instantly thanks to the poor grammar evident in the headline and the body of the text. Most proper news websites still employ sub editors, so lousy spelling and grammar are early warning signals that you’re dealing with a suspicious site.

The next thing to check is the sourcing: where did the minister make these comments? To whom? All this article tells us is that he was speaking “in Johannesburg”. The dearth of detail should signal to tread with caution. If you’ve got the time, you might also Google some key search terms and see if anyone else reported on these alleged statements. Also, is there a journalist’s name on the article? This one was credited to “author”, which suggests that no real journalist was involved in production.

The article is accompanied by some graphic illustrations of a “DIY circumcision”. If you can stomach it, study the pictures. They’ll confirm what I immediately suspected upon reading the headline: this is a rather grisly example of false “news”.

Finally, make sure you take a good look at the website that runs such an article. This one appeared on African News Updates.

That’s a solid name for a news website, but two warning bells rang for me: the first bell was clanged by other articles, which ranged from the truth (with a sensational bent) to the utterly ridiculous. The second bell rang out of control when I spotted a tab marked “satire” along the top. Click on it and there’s a rant ridiculing anyone who takes the site seriously. Like I needed any excuse to exit the site and go in search of real news.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Decoding the News: How To

Get the Tricks of the Trade

Veteran journalist RAYMOND JOSEPH explains how a handy new tool from South Africa can teach you core journalism skills to help you get to the truth

It’s been more than 20 years since leading US journalist and journalism school teacher Melvin Mencher released his Reporter’s Checklist and Notebook, a brilliant and simple tool that for years helped journalists in training.

Taking cues from Mencher’s, there’s now a new kid on the block designed for the digital age. Pocket Reporter is a free app that leads people through the newsgathering process – and it’s making waves in South Africa, where it was launched in late 2016.

Mencher’s consisted of a standard spiral-bound reporter’s notebook, but also included tips and hints for young reporters and templates for a variety of stories, including a crime, a fire and a car crash. These listed the questions a journalist needed to ask.

Cape Town journalist Kanthan Pillay was introduced to Mencher’s notebook when he spent a few months at the Harvard Business School and the Nieman Foundation in the USA. Pillay, who was involved in training young reporters at his newspaper, was inspired by it. Back in South Africa, he developed a website called Virtual Reporter.

“Mencher’s notebook got me thinking about what we could do with it in South Africa,” said Pillay. “I believed then that the next generation of reporters would not carry notebooks but would work online.”

Picking up where Pillay left off, Pocket Reporter places the tips of Virtual Reporter into your mobile phone to help you uncover the information that the best journalists would dig out. Cape Town-based Code for South Africa re-engineered it in partnership with the Association of Independent Publishers, which represents independent community media.

It quickly gained traction among AIP’s members. Their editors don’t always have the time to brief reporters – who might be inexperienced journalists or untrained volunteers – before they go out on stories.

This latest iteration of the tool, in an age when any smartphone user can be a reporter, is aimed at more than just journalists. Ordinary people without journalism training often find themselves on the frontline of breaking news, not knowing what questions to ask or what to look out for.

Code4SA recently wrote code that makes it possible to translate the content into other languages besides English. Versions in Xhosa, one of South Africa’s 11 national languages, and Portuguese are about to go live. They are also currently working on Afrikaans and Zulu translations, while people elsewhere are working on French and Spanish translations.

“We made the initial investment in developing Pocket Reporter and it has shown real world value. It is really gratifying to see how the project is now becoming community-driven,” said Code4SA head Adi Eyal.

Editor Wara Fana, who publishes his Xhosa community paper Skawara News in South Africa’s Eastern Cape province, said: “I am helping a collective in a remote area to launch their own publication, and Pocket Reporter has been invaluable in training them to report news accurately.” His own journalists were using the tool and he said it had helped improve the quality of their reporting.

Cape Peninsula University of Technology journalism department lecturer Charles King is planning to incorporate Pocket Reporter into his curriculum for the news writing and online-media courses he teaches.

“What’s also of interest to me is that there will soon be Afrikaans and Xhosa versions of the app, the first languages of many of our students,” he said.

Once it has been downloaded from the Google Play store, the app offers a variety of story templates, covering accidents, fires, crimes, disasters, obituaries and protests.

The tool takes you through a series of questions to ensure you gather the correct information you need in an interview.

The information is typed into a box below each question. Once you have everything you need, you have the option of emailing the information to yourself or sending it directly to your editor or anyone else who might want it.

Your stories remain private, unless you choose to share them. Once you have emailed the story, you can delete it from your phone, leaving no trace of it.

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

This article originally appeared in the spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Kaya Genç is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine based in Istanbul, Turkey

Jemimah Steinfeld is deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine

Duncan Tucker is a regular correspondent for Index on Censorship magazine from Mexico

Journalist Abraham T Zere is originally from Eritrea and now lives in the USA. He is executive director of PEN Eritrea

Natasha Joseph is a contributing editor for Index on Censorship magazine and is based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She is also Africa education, science and technology editor at The Conversation

Raymond Joseph is former editor of Big Issue South Africa and regional editor of South Africa’s Sunday Times. He is based in Cape Town and tweets @rayjoe

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

18 Jul 18 | Index in the Press

Among the honey-coloured buildings of Valetta’s main street in front of the courthouse is a shrine to Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese journalist murdered on the island last October. Tourists walking through the Unesco World Heritage city this summer might be surprised to stumble upon the shrine—which includes photos and messages—just outside the court buildings. Read in full.

18 Jul 18 | Academic Freedom, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”101526″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Naif Bezwan cannot pinpoint a certain moment in his life in which he decided to pursue academia. For Bezwan, rather, it has been a gradual process of situating his personal narrative within the context of his Kurdish community, within Turkey and within the world.

Bezwan, currently Honorary Senior fellow at UCL Department of Political Science, was born in Diyarbakir, one of the largest cities in southeastern Turkey. A focal point of conflicts between the Turkish government and insurgent groups, the city has a strong tradition of Kurdish liberation movement. Growing up, Bezwan heard the stories of previous generations, including those of his grandparents and relatives, about how they were repressed by the Turkish state. The trajectory of his academic interests was further shaped by his commitment to the universal human struggle for freedom and equality, as well as his determination for democratic reforms through rigorous inquiry. Several areas of his research and teaching expertise include Turkey’s policy towards Kurds and the Kurdish quest for self-rule.

It is not difficult to understand Bezwan’s motivation behind signing the Academics for Peace petition in January 2016. 1,128 academics from 89 universities in Turkey signed the petition, calling on the Turkish government to end its military operations in the Kurdish region and establish negotiations. This peaceful dissent emphatically rejected violence and yet, the signatories were detained and put under investigation. If found guilty of alleged terrorism charges, the petitioners could face between one and five years in prison.

After signing the petition with 37 colleagues from Mardin Artuklu University, Bezwan faced a disciplinary investigation in February 2016. A second investigation was launched just a few months later, in August 2016, after comments he made about the Turkish military incursion in Cerablus, Syria. This time, however, the consequences were even more severe, unjust and absurd.

The interview with the Turkish daily Evrensel was related to the core areas of his academic interests and expertise. Bezwan stressed the danger of using military forces at home and abroad in dealing with Kurdish rights and demands. He was immediately suspended from his position at Mardin Artuklu University, where he was teaching at the time, and completely dismissed through an emergency decree issued in September 2016.

Being deprived of teaching, conducting research or holding any public position, with the possible consequences of signing the Academics for Peace petition hanging over his head, Bezwan felt he had no choice but to leave his life in Turkey for London in November 2016. After almost a year of living in exile, Bezwan became a CARA (the Council for At-Risk Academics) fellow at UCL from June 2017 to June 2018.

Bezwan spoke with Long Dang of Index on Censorship about the events that transpired, his life in the UK, and his vision for Turkey’s future.

Index: What motivated you to become an academic?

Naif Bezwan: I could not really remember a certain point in my biographical trajectories in which I decided to become an academic, let alone pursuing an academic career. The idea of pursuing a career in academia has not been considered something worthwhile and esteemed by my generation of Kurdish and Turkish leftist intellectuals growing up under the brutal military rule in the 1980s. Quite the contrary, embarking on individualistic remedies was seen as a kind of opportunistic behaviour to save your skin, as it were, at the expense of a cause greater than yourself. So I think it has really been a process of gradual becoming rather than a decision at a certain point in time to be an academic. Having said that, it has nonetheless been a clear and conscious orientation towards, and commitment to, certain values, such as democracy, social change, justice, equality and self-determination that motivated us greatly. This motivation, I remember vividly, went hand in hand with an insatiable curiosity about the human condition, history, philosophy, as well as about the situation and destiny of your own society. All this was coupled with a pronounced sense of agency and responsibility for transforming what we perceive to contradict human dignity and freedom. Ultimately, it has been this intensive search for understanding of what has been in the past, as well as for what human dignity and flourishing requires, that led me to become an “academic”, or more precisely, an expelled one.

Index: Why did you become interested in working on Turkey’s Kurdish conflict ?

Naif Bezwan: First, as I indicated, it has been due to the life-world in which my political, cultural and intellectual socialisation, dispositions and positions were coming into being and shaped. I was born in a region of Kurdistan in Turkey, in Diyarbakir, where the Kurdish liberation movement has traditionally been very strong, where an awareness of being member of a distinct society is widespread, where interest in politics, culture and world affairs was distinctively strong. Second, I was raised in a family in which memories of brutal repressions of previous Kurdish generations by the Turkish state, including members of my family, namely my grandfathers and their relatives, were kept alive – their engagements were upheld and their sufferings were told, retold and remembered. A third factor that seems to have formed my orientation during my youth was a growing influence of socialist ideas adopted and defended by various Kurdish organisations and movements throughout 1970s and later on. So all these factors have provided a background to my epistemological interest in working on Turkey and Kurdistan. My time and higher education in Germany during my first emigration, and now in London, have bestowed me with the kind of resources needed to study this problem in-depth from a comparative and historical perspective, and with a degree of freedom necessary to inquiry this complex subject-matter.

To study the various aspects of the Kurdish society and conflicts as a Kurdish scholar almost per se makes you suspicious in the eyes of Turkish state authorities and can lead to your expulsion and imprisonment, as has been the case for many scholars over the years. But it can unfortunately also have consequences of a different kind even in Western countries, such as being branded as biased because of your Kurdish identity or being asked not to criticise the repressive policies leading up to your expulsion and emigration.

Index: On January 2016, 1128 academics signed a petition, entitled “We will not be a party to this crime”, demanding the Turkish government to end military oppression against the Kurdish population. What were your reasons for signing the petition? Were they professional or personal?

Naif Bezwan: It was a combination of both. There was a brutal ongoing war against the Kurdish population, a war whose effects we felt in our daily lives and the lives of our students. I was working at Mardin Artuklu University, which is located at the heart of the Kurdish region at the border between Turkey and Syria. I excruciatingly remember how young people and soldiers were killed everyday, lives and livelihoods destroyed as a result of the termination of the peace process by the government in the summer of 2015. I could not simply stand by and see all these atrocities while the whole community was being destroyed – my students and the people I knew were very affected by this policy of destruction. That is why I signed the petition, knowing that possible severe consequences would be arising from it.

Index: The petition called for a peaceful settlement between the government and the Kurdish population, and yet the government termed it “terrorism”. You were first suspended from your position because of a critical interview on the Turkish military incursion into Syria in August 2016. How do these incidents speak to the government’s system of oppression?

Naif Bezwan: I was suspended from my position for giving the interview with the Turkish Daily National. As an academic for International Relations and Political Science with a specific focus on Turkish domestic politics, political system, foreign policy and Kurdish issue, I argued that the Kurdish issue was essentially entrenched within Turkey, which meant that security would not be possible through more invasion or use of military violence internally and externally. The way to solve the problem, I stressed, was to return to the peace process which had been broken by the government. Only a couple of hours following the interview’s publication, I was called by the faculty administration to be handed down an official document. Upon my arrival, I was given a letter. This letter, in which a reference was made to the interview, was nothing but an order for my suspension that had been signed by the rector of the University. So I was immediately suspended from my position and then requested to give my defence as to why I gave the interview. In my defence, I emphasised that the interview was related to the core area of my expertise, and that suspension of academics and suppression of free speech cannot be the way in which academics arguments should be exchanged and universities function. My assessment, I added, might have been wrong or problematic. If so, however, it should have been responded through counterarguments instead of punitive measures. I have not yet been notified of the outcome of the administrative inquiry, but instead have been completely expelled from my position and public service through a decree-law in September 2016.

Index: Could you describe the hostile environment in Turkey after the failed coup attempt of July 2016?

Naif Bezwan: The coup attempt was a vicious attempt against democracy, but the government used it as the pretext to extend the dimension and size of oppression. In the aftermath of the failed coup, Erdogan said something very treacherously revealing – he depicted the coup as a kind of blessing. Why was it so? Well, this “blessing” was used first to intimidate the whole range of oppression, and second to consolidate his power. It was clear that it would be difficult to live in the country and therefore my partner and I decided to leave the country for the UK on 9th November 2016.

Index: How has life in the UK been for you?

Naif Bezwan: I think every form of forced exile contrary to freely chosen ways of immigration in search for a better life is painful. You are all of a sudden cut off from many things that make your life meaningful – your work, your relationships, your friends and family. After having migrated from Turkey to Germany in 1991, I freely decided to return to Turkey in January 2014, in the hope of doing something meaningful. I had just settled down and once again I was compelled to leave the country. The choice I had to make was between going into a new exile or being deprived of many things and activities that defined me and my way of life.

Being confronted with a forced immigration, one also needs to look on the bright side, try to create new possibilities and involve oneself in activities that would give meaning to one’s life again. In June 2017, almost a year after my arrival in London, I was granted the CARA fellowship at the Department of Political Science at UCL. Thanks to the fellowship, I was able to more systematically and continuously work and promote my studies and public engagement. I have completed two academic articles during the first months of my fellowship. I have been able to do a lot of research and participate in many academic conferences. In a group of other academics and friends, I became involved in establishing a London-based charity, the Centre for Democracy and Peace Research, which provides substantial support for our friends and colleagues back home. In all, being in the UK has been an uplifting opportunity, allowing me to continue with my studies and with my life.

Index: What is your perspective on the newly-expanded powers of Erdogan and their implications for the freedom of academics? What sort of support do you think is necessary for freedom movements to gain momentum? Could momentum be gained from within the country, or is some form of international intervention fundamental?

Naif Bezwan: As far as the character of the new regime is concerned, I think we have to keep in mind that the constitutional changes that introduced the new government system was made under a state of emergency. Opposition was silenced and intimidated, and there was no free press or free speech. This is very indicative of the character of the current regime. It is essentially an authoritarian, autocratic regime based on arbitrariness, with severe restrictions on free speech and a range of repressive policies at its disposal. For example, just three days before Erdogan was sworn in as president, there was an emergency decree through which about 18,000 civil servants, including academics, were dismissed. The message that the government wants to send is: we celebrate our victory through the intimidation and suppression of people, depriving them of basic rights, of the basis for life in dignity and freedom.

Given the nature of the current regime, two major outcomes seem to be possible. First, if there is a convergence between the parliament majority and president, which is currently the case, it would allow the president to exercise a constitutional dictatorship, in which the president can act in absolutely unbounded manners, since the dictatorial exercise of state authority is grounded in the very nature of the constitution itself. The current regime is authoritarian and autocratic in character, based on and emerged out of, extensive policies of intimidation, expulsion, fear and war-mongering. The other option would be a divergence between the parliament majority and president, which would result in an illiberal, dysfunctional regime. So: we had a choice between two equally undemocratic, unreasonable and repressive ways of governing the country. What makes things even worse is the fact that the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) – the far-right, anti-kurdish, anti-western, utterly racist party – now provides the president and his new regime with the necessary majority.

Given the fact that the country is increasingly becoming a big prison for the Kurds, minority groups, academics and critical voices, the work of the Kurdish and Turkish diaspora, as well as the support of the international community, is essential to strengthening democratic opposition and forces of transformation in the country. Due to the monopolization of the press in Turkey by the government, critics have no free space for acting and organizing themselves. This is why it is so important for organizations like Index to give voice to the people, their suffering and their resistance, in Turkey and beyond.

Index: Do you have hope that you will be able to return to Turkey, and pick up from where you left off?

Naif Bezwan: Going through all this process and being affected by it make you perhaps particularly sensible to the injustices directed at other people. I feel it incumbent upon me to do more academic work and be even more involved in civic duties to change the current situation and the utterly repressive regime. It is not an easy task at all. It requires patience and perseverance on the one hand, and creativity, solidarity and imagination on the other to generate new alternatives. I feel a responsibility to contribute the realising democratic and peaceful conditions in Kurdistan, Turkey and beyond.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Academic Freedom” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Jul 18 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns -- Featured, Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship welcomes a European Parliament recommendation for the EU to ensure that Azerbaijan frees its political prisoners before the negotiations on a new deal between the EU and Azerbaijan are concluded. The recommendation mentions the jailed investigative journalist Afgan Mukhtarli as being among the “most emblematic cases”.

The talks on the new agreement that will govern relations between the EU and Azerbaijan were launched in 2017 and could be concluded in 2019. Azerbaijan has an extremely poor track record on human rights, as highlighted in a 2017 analysis by the European Parliament.

The European Parliament’s current recommendation calls on the EU to ensure that the deepening of relations with Azerbaijan is made conditional on upholding and respecting democracy, the rule of law, good governance, human rights and fundamental freedoms. It calls on the EU to underline the importance of a free and independent media and to ensure strengthened EU support, both political and financial, for a free and pluralistic press in Azerbaijan.

Joy Hyvarinen, head of advocacy at Index on Censorship, said: “We urge the EU to take a strong stand on media freedom and human rights in its talks on a new agreement with Azerbaijan. This is an opportunity for the EU to demonstrate global leadership and to promote fundamental European values. Freeing political prisoners such as investigative journalist Afgan Mukhtarli should be a priority.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1531833660337-cb577e58-d3f0-4″ taxonomies=”7145″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jul 18 | Global Journalist (Arabic), Journalism Toolbox Arabic

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=””][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

في عام ٢٠٠٩ ، أعيد انتخاب الرئيس محمود أحمدي بعد حولة انتخابية مثيرة للجدل كان منافسه فيها مير حسين موسوي. أدّت نتيجة الانتخابات إلى غضب شعبي عارم وظهور حركة احتجاجية عرفت باسم الحركة الخضراء، وامتلأت الشوارع بمظاهرات تدعو إلى إقالة أحمدي نجاد. خلال العامين التاليين ، شنت السلطات الإيرانية حملة قمعية عنيفة فسجنت الصحفيين والمعارضين السياسيين وكان الصحفي أوميد رضائي أحد هؤلاء.

كان طالب الهندسة الميكانيكية الإيراني المولد رئيس تحرير مجلة فانوس ، وهي مجلة طلابية تم حظرها بعد تأييدها الحركة الخضراء في ايران.ولقد تم اعتقال رضائي في أكتوبر ٢٠١١. في عام ٢٠١٢ ، هرب إلى العراق ، وفي عام ٢٠١٥ ، شق طريقه إلى ألمانيا. في فبراير ٢٠١٧ ، أطلق موقعه متعدد اللغات، “بيرسبكتيف ايران” (وجهة نظر إيران) ، لتغطية أخبار إيران، بشكل أساسي باللغة الألمانية. كما أنه عمل ككاتب حر في بعض وسائل الإعلام الألمانية منذ نفيه. يهدف رضائي لإظهار العديد من الجوانب الخفية للحياة في ايران وطبيعة الحياة اليومية لشعبها.

اندكس أون سنسرشب: أصبحت صحفيًا في سن مبكرة جدًا. ما الذي جعلك تختار هذا المسار في وقت مبكر جدا؟

أوميد رضائي: يثير فعل سرد القصص حماسي ولقد فعلت ذلك منذ الطفولة. كان ذلك أول شيء تعلمته عن نفسي. أولاً من خلال قراءة القصص – سواء القصص الصحفية والإعلامية أو القصص الخيالية – ثم سرد القصص. عندما كنت في العاشرة من عمري ، قمت بتأسيس مجلة صغيرة في المدرسة الابتدائية لكنها فشلت بعد طبعتين فقط. بحلول سن الخامسة عشر، قمت بتأسيس مجلة ثانية في السنة الأولى من المدرسة الثانوية. نُشرت هذه المجلة لمدة عام واحد ، وبحلول سن السابعة عشر، أسّست المجلة التالية التي تم توزيعها في جميع المدارس الثانوية في مدينتنا فجلبت انتباه السلطات إليها للمرة الأولى. لكن ما زلت أعتقد أن هذا كان يستحق كل العناء لأنه أعطاني الفرصة لسرد القصص. إنه الشيء الأكثر بهجة في هذا العالم.

اندكس أون سنسرشب: لماذا غادرت إيران؟

أوميد: برزت فكرة مغادرة البلاد في ذهني بينما كنت جالسًا في زنزانة بمفردي لأيام وليال دون أن أتمكن من رؤية أي شخص أو التحدث إليه. كنت أسأل نفسي كم من الوقت يمكنني تحمل هذا الوضع. عندما تم الحكم علي بالسجن لمدة عامين ، كان علي أن أفكر في الأمر بجدية أكبر. هناك أسباب كثيرة – شخصية وسياسية – أدت إلى اتخاذي قرارا مغادرة البلاد. أقول أن أهمها – وهو سبب لا يزال ينطبق – هو أنني افتقدت حريتي. أولا وقبل كل شيء حرية التعبير ، ولكن أيضا حرية اختيار نمط حياتي.

اندكس أون سنسرشب: أخبرنا عن هجرتك سيراً على الأقدام إلى العراق.

أوميد: بصرف النظر عن الأخطار والأمور المادية والتقنية ، لن أنسى أبداً اللحظة التي عبرت فيها الحدود، اذ شعرت كما لو أنني كنت قد عبرت نهاية الأرض. لن أنسى أبداً كيف نظرت إلى الأرض التي كانت أرضي ووطني. أعتقد أن هناك فرقا كبيرًا عندما تغادر البلاد بالطائرة ولا ترى تلك “الحدود”. ولكن عندما تعبرها سيرًا على الأقدام وتعرف أنك لن تعود قريبًا فهذا سوف يشعرك بحزن عميق.

اندكس أون سنسرشب: أنت كاتب نشط عبر الإنترنت. كيف تعتقد أن الإنترنت قد غيرت الصحافة؟

أوميد: لقد بدأت مسيرتي المهنية عبر الإنترنت وأنا الآن أدرس الصحافة الرقمية. هي الآن جزء مني وأنا جزء من العالم الرقمي. بصراحة ، ليس لدي أي فكرة عن كيفية كانت الصحافة المهنية تعمل قبل أن تكون على الإنترنت. لكن حقيقة أني لازلت أستطيع تغطية إيران والشرق الأوسط، على الرغم من أنني ابتعدت عنها لسنوات، فانه يرجع الفضل في هذا مباشرة إلى الإنترنت وعالم الإنترنت. بصرف النظر عن جميع المشكلات التي نواجهها ، فإننا أقرب إلى بعضنا البعض بسبب الإنترنت. والأهم من ذلك، يعطينا العالم الرقمي – نحن الصحفيين – المزيد من الإمكانيات لمجابهة الأنظمة غير الشرعية في جميع أنحاء العالم.

اندكس أون سنسرشب: كيف استقرت بك الحياة بعيدا عن وطنك؟

أوميد: لن يكون صحيحًا إذا قلت إنني لا أشتاق إلى مسقط رأسي ، والمدينة التي درست فيها ، والأشخاص الذين أحبهم — والذين يحبونني. لكن خلاصة القول هي أن الوطن هو المكان الذي يكون فيه الفرد حراً ، حيث يمكن للمرء أن ينمي نفسه ويعيش بكرامة. لديّ الكثير من الذكريات الجيدة عن إيران ، وأنا أفتقد الكثير من الناس هناك ، لكني لم أعتبر إيران وطنا، وينطبق الأمر نفسه هنا في ألمانيا. وطني هو لغتي. لا أقصد الفارسية. أنا أحب اللغة الألمانية بقدر ما أحب لغتي الأم ، وهذا ينطبق على اللغة الإنجليزية واللغات التي أتعلمها الآن. وطني هو القصة التي أرويها اذ أستقر في حياتي الجديدة من خلال سرد القصص. أنا مقتنع تماما بأن رواية القصص فقط يمكنها أن تنقذنا.

https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2018/07/journalism-in-exile-iranian-journalist-omid-rezaee-believes-storytelling-can-save-us/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

16 Jul 18 | Index in the Press

A public vote is set to launch this week to find the nation’s favourite banned book. It is taking place in the run up to the week-long celebration of banned books in September. From Wednesday 18th July until 22th August, the Banned Books censored summer reads campaign will suggest five titles each fortnight which have been banned, censored or challenged. Index is the lead partner in a coalition of organisations celebrating Banned Books Week in the UK. Read the full article.

16 Jul 18 | Global Journalist, Iran, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In 2009, incumbent president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won Iran’s highly contested election against Mir-Hossein Mousavi, which led to public outrage and the formation of the Green Movement, filling the streets with demonstrations calling for Ahmadinejad’s ouster. For the next two years, Iranian authorities ran a campaign of jailing journalists and political opponents. Journalist Omid Rezaee was one such detainee.

The Iranian-born mechanical engineering student was the editor-in-chief of Fanous, a student magazine which was banned for standing with the Green Movement. Rezaee was arrested in October 2011.

In 2012 he fled to Iraq, and in 2015 he made his way to Germany. In February 2017 he started his own multilingual website, Perspective Iran, where news about Iran is mainly reported in German. He has also been working as a freelance writer within German media outlets since he was exiled. Rezaee aims to show the many hidden aspects of Iran and the nature of the everyday lives of its people.

Index on Censorship: You became a journalist at a very young age. What made you choose this career path so early?

Omid Rezaee: Storytelling excites me and has done so since childhood. It’s the first thing I learned about myself. First by reading stories – whether journalistic and media stories or fiction – and then by telling stories. When I was 10, I founded a small magazine in the primary school which failed after only two editions. By 15, I founded the second one in the first year of high school. This one was published for one year and by 17 I founded the next one which was being distributed in all high schools of our town and which brought me to the attention of the authorities for the first time. But I still think this was worth all the troubles because it gave me the opportunity to narrate stories. It’s the most delightful thing in this world.

Index: Why did you leave Iran?

Omid: The idea of leaving the country popped in my mind while I was sitting alone in a cell for days and nights without being able to see or talk to anyone. I was asking myself for how much longer I can bear this situation. When I was sentenced to two years in prison, I had to think about it more seriously. There are many reasons – both private and political – which led to my decision to leave the country. I would say the most important one – which still applies – is that I missed my freedom. First and foremost the freedom of speech, but it’s also freedom of lifestyle.

Index: Walk us through your migration on foot to Iraq.

Omid: Apart from the dangers and physical and technical things, I would never ever forget the moment I crossed the border as if it was the end of the earth. I would never forget how I looked back to the soil, the ground which used to be my homeland. I guess there is a huge difference when you leave the country by a plane and don’t see that “border”. And when you cross it on foot and you know, you won’t be back soon. This grieves you deeply.

Index: You are an active writer online. How do you think the internet has changed journalism?

Omid: I’ve started a professional career online and I am now studying digital journalism. By now it’s part of me and I’m part of the digital world. Honestly, I have no clue how the professional journalism used to work before it was online. But the fact that I can still report on Iran and the Middle East, even though I’ve been away for years, is directly due to the internet and online world. Apart from all the troubles we’re facing, we are closer to each other because of the internet. And more important: the digital world gives us – the journalists – more possibilities to strive against illegitimate authorities all over the world.

Index: How have you settled into life away from home?

Omid: It’s not true if I say I don’t miss my hometown, the city I studied in and the people I loved – or still love – and who love me. But the bottom line is that home is where one is free, where one can develop himself and live with dignity. I have a lot of good memories of Iran and I deeply miss a lot of people there, but I never considered Iran as a home, and it’s the same here in Germany. My home is my language. I don’t mean Farsi; I love German just as much my mother tongue, and this applies to the English language and the languages I’m learning right now. My home is the story I’m telling and I’m settling into my new life by telling stories. I am firmly convinced that only storytelling can rescue us.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row disable_element=”yes”][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/6BIZ7b0m-08″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship partner Global Journalist is a website that features global press freedom and international news stories as well as a weekly radio program that airs on KBIA, mid-Missouri’s NPR affiliate, and partner stations in six other states. The website and radio show are produced jointly by professional staff and student journalists at the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism, the oldest school of journalism in the United States. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Jul 18 | Index in the Press

In the 15 years I have known Khayrullo Mirsaidov, I have often called my friend and colleague an idiot.

The Webster dictionary defines an “idiot” as”a very stupid or foolish person”. That describe accurately anybody who, 25 years after the Soviet Union broke down, still fights for free media and democracy in a country like Tajikistan. Read in full.

14 Jul 18 | Index in the Press

Originating in South Side Chicago at the start of the decade with breakout artists such as Pacman and Chief Keef, drill (slang for gun) is a strand of trap music defined by a slower tempo of 70 beats per minute (with trap at 140 and grime at 160), layered with visceral, often violent lyrics; sometimes bloated with bravado, sometimes unreservedly nihilistic. Read full article.

13 Jul 18 | Tim Hetherington Fellowship

During my time as the LJMU Tim Hetherington Fellow and working at Index on Censorship, I have really had the opportunity to develop my skills as a journalist, as a writer and as someone in a professional capacity. Read in full at JMU Journalism.

13 Jul 18 | Magazine, News and features, Volume 47.02 Summer 2018

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

In the summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine Caroline Muscat takes a closer look at the truths this year’s European Capital of Culture, Valetta in Malta, is hiding

[/vc_column_text][vc_single_image image=”101057″ img_size=”large” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

The sprawl of construction sites represents the reality of Malta. It’s a sign of progress, never mind the fact that planning laws are farcical. The country’s affluence is shown by the number of cars on the road, never mind the traffic congestion. Its freedom is evidenced in the number of media outlets and news portals, never mind the fact that they all offer similar content. It’s all about appearance, not substance. Scratch beneath the surface and the problems start to appear.

“National pride has reached historic levels,” Prime Minister Joseph Muscat told more than 100,000 people who flocked to the nation’s capital, Valletta, for its inauguration as Europe’s Capital of Culture 2018. The announcement was made as the country was grappling with the assassination of its most prominent journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, and as accusations of a collapse in the rule of law continued to haunt Malta.

Restaurants offering mouth-watering dishes are found across the length and breadth of Malta’s islands, but while digging into a bruschetta few stop to question the sudden influx of Sicilian restaurants that are suspected of being money-laundering fronts for the Sicilian mafia.

Operation Beta, led by the Italian authorities in 2017, culminated in the arrest of 30 people as part of a major clampdown on illegal gaming activities and money laundering linked to a Sicilian family, the Santapaola-Erculanos, linked to the mafia by the Italian media. Almost a year later, Italian police cracked an operation involving Sicilians, Maltese and Libyans smuggling Libyan fuel into the European market. Once again, a link to the Santapaola-Erculano family emerged. A look at the histories of the mafia clans reveals deep family connections to Malta as a hub from which to extend their reach and profits.

The links date back to 1974, when a Sicilian man and his bride went to the Maltese island of Gozo on their honeymoon. They loved the island so much they frequently returned. To the locals who interacted with him in Pjazza San Frangisk, in Victoria, he was known simply as Toto.

But Toto was Salvatore Riina, the mafia boss who terrorised Sicily and made the Italian State tremble while making friends in Malta.

Over the years, Malta has continued to attract shady characters, including politically exposed politicians, from countries including India, Ukraine and Azerbaijan. There are clear risks in probing too deeply into the shadows of modern Malta – not that this is obvious to anyone landing in the country for a fortnight of sun and sea. Popular events, such as the annual music festival the Isle of MTV, continue to offer a distraction on the islands that were once a safe haven for tourists and locals. But the recent release of the Panama Papers linked a Maltese minister, Konrad Mizzi, and the prime minister’s chief of staff, Keith Schembri, to $1.6m payments to Dubai companies. Both deny the claims of payments.

It is now clear that a political party elected in 2013 on the promise of change was not thinking of adding transparency or media freedom. Since the Panama Papers revelations, journalists have piled up stories of scandals, but nothing has changed. Deals selling off the country’s assets continue to be made, shrouded in secrecy. And in the midst of all this, calls for justice for an assassinated journalist continue to echo in the air.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column][/vc_column][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Few stop to question the sudden influx of Sicilian restaurants that are suspected to be money laundering fronts” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Daphne Caruana Galizia was killed because of what she exposed. Seven months later, the institutions that failed to protect her are the same institutions that are failing to bring those who ordered her killing to justice. Every month, on the date marking her death, citizens gather to call for justice in the country’s capital. They gather in front of a makeshift memorial before the law courts as a reminder that justice has not been served. Every time, they know they will see each other the following month because nothing will have changed. Yet their presence, and the flowers and candles placed at the foot of the monument, serve as a reminder to the authorities that they will never forget.

Those who mention her name, those who refuse to bow to a society bent by corruption, are insulted and threatened. Journalists and activists keep being reminded of the untold damage they are doing to the country’s reputation. Malta’s image is everything, but it is not what it seems.

When confronted by the news that the European Parliament was sending a delegation to investigate Malta’s anti-money laundering rules, Muscat said: “I invite them to come over to see what a fantastic country we are.” But the Paradise Papers had already shown just how “fantastic” Malta s by casting a dark cloud over its economic miracle.

While workers in other countries have borne the brunt of austerity, the Maltese have never had it so good, shielded by an economic system which relies partly on enticing shell companies to Malta by offering a favourable fiscal regime, in addition to a growing dependence on i-gaming and construction. In addition, Malta’s controversial “sale” of European passports continues, despite concerns about the erosion of democracy.

Living in Malta as a journalist one experiences the stark reality of it all. Those exposing corruption are ostracised and vilified. Their voices are drowned out by the millions spent on the marketing machine to promote Malta and clean its image. Journalism is undermined through an almost complete domination of the narrative by the government – millions of euros spent on PR ridicules weeks of investigative journalism. Government advertising drowns out calls for a democracy that ends corruption and protects freedom of speech.

On 16 May, Labour MP Rosianne Cutajar stood up in parliament and spent 30 minutes criticising the publication of a six-month investigation by The Shift News that exposed pro-government secret Facebook groups with thousands of members posting threats against activists. These posts included threats towards anti-corruption activist Tina Urso, whose home address was also published on the site. Urso filed two complaints with the police, but wasn’t offered any protection.

The MP also said I was sowing the seeds of hatred left behind by Caruana Galizia by attacking the government. Compare this with the exposé of anti-Semitism in the UK Labour Party and the media scandal that followed. In Malta, the scandal was the journalist who dared to speak truth to power.

Caruana Galizia had written: “Malta is in a dangerous place, and now we can no longer say that it is corrupt politicians who have brought it to this point, for it can no longer be denied that those corrupt politicians are a reflection of society.”

In this scenario, the protection of journalists is critical in a landscape that is intolerant of independent thought.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Caroline Muscat is the co-founder of The Shift News, based in Malta

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Click here to read about the other articles in the issue.

The latest issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Trouble in Paradise, Escape from Reality: what holidaymakers don’t know about their destinations is out now. Buy a subscription. Buy a print copy from bookshops including BFI, Serpentine and MagCulture (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), and Red Lion Books (Colchester), or via Amazon. Digital versions available via exacteditions.com or iTunes.

Finally, don’t miss our regular quarterly magazine podcast, also on Soundcloud, including an interview with the founder of the Rough Guides, Mark Ellingham. Come by and visit us.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”89160″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229108535157″][vc_custom_heading text=”Do not disturb” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422011399822|||”][vc_column_text]2011

In 2011, Charles Young reported that writers, journalists and even DJs are falling foul of Malta’s censorious laws[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”64776″ img_size=”213×287″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064220008536796″][vc_custom_heading text=”Social disturbance” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422015571882|||”][vc_column_text]March 2015

News footage provided by readers and viewers has entered a new era, where we’re faced with more propaganda, hoaxes and graphic detail than ever before. Vicky Baker looks at the increasingly tough verification process at the BBC’s user-generated content department[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229308535477″][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422018769585|||”][vc_column_text]Spring 2018

Attacks on journalists are escalating in areas formerly seen as safe,

including the USA and the European Union, says Danyaal Yasin[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Trouble in Paradise” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2F2018%2F04%2Fthe-abuse-of-history%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2018 issue of Index on Censorship magazine takes you on holiday, just a different kind of holiday. From Malta to the Maldives, we explore how freedom of expression is under attack in dream destinations around the world.

With: Martin Rowson, Jon Savage, Jonathan Tel [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”100843″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/newsite02may/2018/06/trouble-in-paradise/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fnewsite02may%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Jul 18 | Index in the Press

The hunt for the person or people who ordered the murder of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in Malta last October appears to be making little progress. Caroline Muscat reports that the government there instead seems concerned with burnishing the country’s image. Read in full.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]