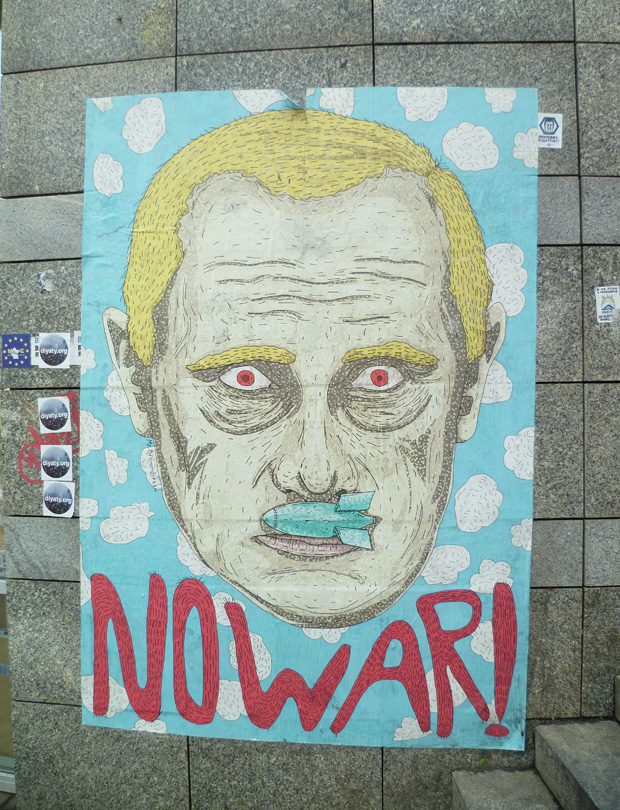

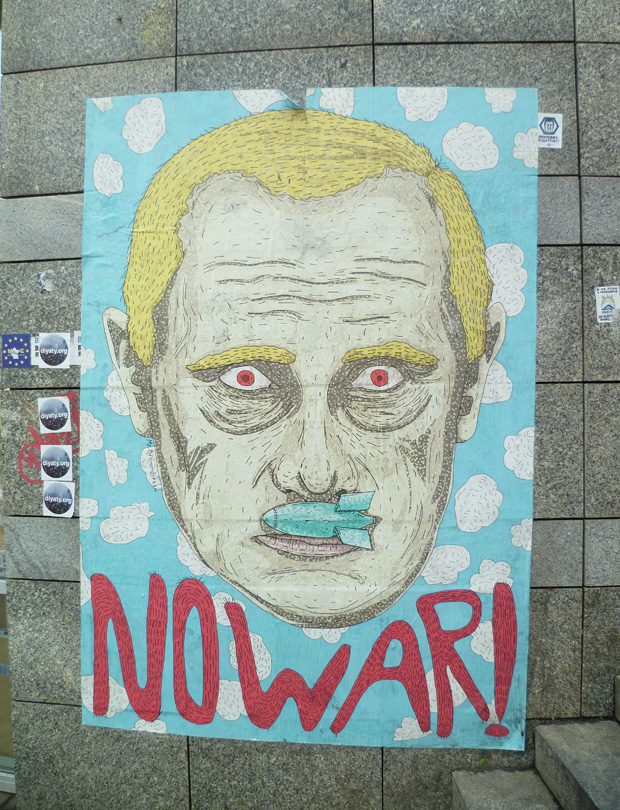

23 May 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Ukraine

(Image: Index on Censorship)

Ukraine is seeing a “concerning pattern of grave violations of media freedom commitments” warns OSCE press freedom boss Dunja Mijatovic in a new report.

“As we know too well, in times of crisis and conflict, journalists and members of the media are among the first to be attacked, both physically and psychologically. Because those in power during periods of conflict demand complete control of all information free media is often their first target,” the report, published on Friday, states. Covering the time between 28 November 2013 and 23 May 2014, these are the three key findings.

1) Journalists face serious threats to their safety

There have been “nearly 300 reported cases of violence against journalists, including murder, physical assaults, kidnappings, threats, intimidations, detentions, imprisonments, and damage and confiscation of equipment”. These attacks are divided into two phases — the first covering the Maidan protests in Kiev, and the second the ongoing crisis in the east of the country. In Maidan, journalist Viacheslav Veremyi was killed, while almost 200 others were victims of violence. These include the over 40 journalists who were assaulted while covering protests on 13 December 2013. “In some cases,” the report states, “journalists were specifically targeted by law enforcement despite displaying clear identification as members of the press.” Since March, attacks on journalists in the east have intensified and gone without prosecution — something that “points to the breakdown of the rule of law in the parts of Ukraine affected by conflict”. On 18 May, Ukrainian military arrested two Russian journalists from LifeNews, while two journalists from Otkritiy Krymskiy Kanal were detained, interrogated, beaten and had their equipment seized by a group of people wearing military uniforms. Journalists in Crimea — recently annexed by Russia — who are not considered loyal to the region’s authorities, and who refuse to change citizenship, have been faced with regular threats, harassment and the possibility of eviction.

2) Ukraine is in the middle of an information war

There have been a number of accusations of the media being used to disseminate propaganda. “Propaganda and the deterioration of media freedom combine to fuel and contribute to the escalation of conflict, and once it starts they contribute to its escalation,” the report states. Among other thing, broadcasting stations “and related infrastructure” in Crimea, Sloviansk, Donetsk and Luhansk, have been attacked by unidentified and often armed individuals who supplanted regularly scheduled television programming with Russian state media. In March, the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council of Ukraine ordered all cable operators to stop broadcasts of several Russian state TV channels. “No matter how loud and outrageous certain voices are, they will not prevail in a competitive and vibrant marketplace of ideas,” the report argues. “Therefore, any potentially problematic speech should be countered with arguments and more speech, rather than engaging in censorship.”

3) Media workers are being denied entry

In the past months, the OSCE has intervened in some 30 cases of journalists being denied entry into Ukraine and Crimea. “I have serious concerns about excessive restrictions on such travel, which ultimately affects the free flow of information and free media,” writes Mijatovic. Recently, Russia Today’s Arabic news crew, who travelled to Kiev to cover Sunday’s presidential election, were denied entry at immigration. Two crews from the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) were not allowed to enter Ukraine, despite having all required accreditations. On a related note, a Rossiya-1 TV crew were this week deported from Ukraine.

This article was posted on May 23, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

23 May 14 | News and features, Pakistan, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

Shahidullah Afridi’s roots are in a village in the Bara administrative division of the Khyber agency. For the last four years, Afridi has been living in the neighbouring city of Peshawar, but keeps a keen eye on events at home.

He was shocked when he heard that last week, the outlawed militant group, Lashkar-e-Islam (LI) had started a rather strange recruitment drive in his village that asked residents to enrol at least one of their sons to madrassas run by LI or pay Rs 400,000 (£2,397.96) as penalty.

Afridi is glad he left when he could. “I have a five-year old son. I don’t want my son to study in a madressa. I didn’t and I consider myself a fairly good Muslim,” he said, adding: “If you don’t study in a school [as opposed to a madressa], you don’t find work.”

The news was confirmed by Zahir Shah Sherazi, Dawn TV’s bureau chief in Peshawar who also reports on FATA and KPK. “My sources tell me that A4 sized posters have been plastered all over the marketplace in the Malik Din Khel area, controlled by LI, demanding locals put their sons into the seminaries run by them,” he told Index, adding: “They also said admission in madrassas other than theirs would not be acceptable.”

Afridi has not visited his village since he left. “I neither sport a beard nor do I wear a skull cap,” he told Index by phone from Peshawar, where he works as a daily wage earner.

Ambreen Agha, a research assistant with New Delhi’s Institute for Conflict Management, said Mangal Bagh assumed the leadership of LI in 2007, emerging as a new face of extremism and Islamic fundamentalism. “He imposed his version of the Shariah, issuing diktats against women’s education, making it compulsory for men to keep beards and forced women to wear burqa.”

Neither the Pakistani government nor the army took any actions.

“It shows the incompetency of the establishment,” said Agha, adding: “Eight years of Bagh’s control of the area says enough about the will of the Pakistani state in dealing with the militants. ”

To Farahnaz Ispahani, public policy scholar with the Washington D.C. based-Woodrow Wilson Centre and a former parliamentarian, it’s a “reflection of the virtual end of pluralism and choice in Pakistan”.

“Extremist ideology has partnered with criminality; the so-called Lashkar-e-Islam is engaging in mafia-like extortion but seeking respectability as an Islamist insurgent group,” she told Index.

Sherazi terms Bagh a “criminal” adding that his is not an ideological fight. “He is just doing business — in drugs,” he said.

Journalist Taha Siddiqui, winner of this year’s Albert Londres Prize, has travelled extensively in the area controlled by Bagh as well as written about militancy. Siddiqui told Index: “Locals that I have spoken to tell me that the smuggling trade from Bagh’s area is most lucrative.”

But why has the state allowed Bagh to flex his muscles with such impunity?

Khyber agency is on the last leg of the NATO supply route before it enters Afghanistan. Siddiqui says it suits the Pakistani security establishment to keep the area lawless. “It helps to keep it infested with militants — and using the latter as proxies to keep the pressure on NATO when it’s exiting.”

In addition, he said, Pakistan had often hinted at acquiring the leftover military equipment. “What better way to have their way if the ISAF does not cooperate — keep attacking the supply route — and that is only possible if they have proxies there,” he explained.

At another level, Siddiqui said the state is using militancy to achieve some other objectives. “They created Ansar ul Islam [another banned militant group] to counter LI in Khyber agency. To me, it proves that they do not want to eradicate militancy, but keep arming one group to disarm the others, especially those who have turned against them.”

Bagh’s enrolment ultimatum is just another example of how emboldened the militant outfits have become and in comparison how weak the Pakistani state appears.

However, there is time still and if the state is sincere in protecting the next generation of children from embracing militancy, Siddiqui said, the civilian government should ask the military what it has been doing in Khyber agency for almost half a decade. “If it’s fighting militancy, then this should not be the result. On the other hand, if it is not, those responsible should be held accountable and heads should roll so that an effective counter-terrorism policy is actually implemented which is not limited to paying lip-service to gain international sympathy and aid through deceit and cheating that Pakistan has come to be known for.”

This article was posted on May 19, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 May 14 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Politics and Society, Ukraine

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Walking around Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti square, months after the protest that enveloped the city and toppled the corrupt government of Viktor Yanukovych died down, is a strange experience. International attention has understandably shifted, the images now beamed across the world are from the ongoing crisis in eastern Ukraine. The capital is calm these days, so I don’t know exactly what I was expecting as I made my way down Mykhailivska street.

Tents still populate Maidan, with young and old lounging, talking and cooking in the May sunlight. I walked past sandbag barricades, and ones made of tyres painted in the blue and yellow of the Ukrainian flag. There were flags were everywhere — EU, American, British, and many more. I walked past the independence monument, juxtaposed against the new year tree, covered by protesters in posters, and yet more flags. Music was blaring out from the small stage facing these towering structures. The lyrics I couldn’t understand, apart from the cry of “Ukraina” in the chorus. I made my way past the Maidan press centre, towards a bridge which had a large banner emblazoned with names and faces hanging from it. The Hotel Ukraina behind me, I looked out over the square.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

The only thing missing was the crowds. It felt like they had just taken a break — gone for lunch, to return at any moment. Perhaps I arrived with a naive “out of sight, out of mind”, mentality, subconsciously assuming that the square would to an extent have been cleared out. But Maidan seems to be, for now at least, a living monument to the profound change, and crisis, Ukraine is going through.

It was against this backdrop, and with the country’s general elections set for this Sunday, I travelled to Kiev to take part in the conference Ukraine: Thinking Together. The brainchild of Yale University history professor Timothy Snyder and the New Republic’s Leon Wieseltier, its purpose was “to meet Ukrainian counterparts, demonstrate solidarity, and carry out a public discussion about the meaning of Ukrainian pluralism for the future of Europe, Russia, and the world.” The guest list included academics like Bernard-Henri, Lévy Timothy Garton Ash and Ivan Krastev, and journalists like The New York Times’ Roger Cohen and The Atlantic’s David Frum. Former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt also made an appearance at the welcome reception.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

One could question what, if any, effect the discussions of a group of intellectuals might have on the very real crisis on the ground. Over the weekend, there were among other things, a Crimean Tartar journalist was detained in Simferopol, while the Ukrainian military arrested two Russian reporters. But Kiev-based journalist Maxim Eristavi told me, and tweeted, that it was “surreal” to have the “intellectual powerhouse of the West in one room in Kyiv”. If nothing else, organising a big-name gathering to talk about Ukraine, in Ukraine, makes a bold statement — and one likely to be heard all the way to Moscow.

A range of topics were tackled in five days of panel debates and public lectures. The Maidan protest was applauded, with Wieseltier in his opening remarks calling it “one of the primary sites of the modern struggle for democracy”. Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, called Maidan a geopolitical move, but by a people rather than a government.

(Image: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Bernard-Henri Lévy spoke of his recent visits to eastern Ukraine, explaining that while they might be fewer than in the Maidan, there are people in these areas who support a unified Ukraine. He contested what he believed to be the image presented in western media that people in the east are all separatists. While the point was made that flags, national symbols and the Maidan movement is not perceived as positively in all parts of the country as in Kiev, Constantin Sigov, professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla, argued that the Ukrainian crisis is first and foremost civil and political, not one of identity.

Russia’s foreign policy and Russian President Vladimir Putin were unsurprisingly recurring themes. “He has values. They are not our values, but they are values,” said François Heisbourg, chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, talking on the panel of geopolitics after Crimea. Writer Paul Berman argued, in the same panel, that Putin is acting from a position of weakness, and fear that Russia is not stable. Others, meanwhile, were uncomfortable with the term geopolitics, saying it legitimises Putin’s world view.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Russia’s propaganda strategy was also a hot topic and elicited strong responses, with one audience member referring to it as a weapon of mass destruction. “Propaganda is the beginning of bloodshed, it precedes bloodshed,” said Alexandr Podrabinek, editor-in-chief of Prima information agency, on the panel discussing whether rights make us human. State-run news channel RT, formerly Russia Today, got several mentions. Academic Anton Shekhovtsov argued that RT gives space to democratic consensus in its coverage, but also to left-wing, far right and libertarian narratives, and even conspiracy theories. Because each is treated in roughly the same way, the democratic narrative becomes just one of many. He said this explains why RT appeals to some people in the west, but stressed that they’re pushing an overall Russian agenda.

Podrabinek, despite dubbing RT “hateful”, argued that while there might be a temptation to shut down views we don’t like, this is not a good way of confronting them. If we want freedom of expression, he said, we can’t do that. On a related note, Carl Gersham argued that while Ukraine needs to be supported economically and militarily, they also need support in modernising the media landscape, to foster internal dialogue.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

And while the regime was criticised by speaker after speaker, ordinary Russians and their rights were not forgotten. Sergei Lukashevsky, director of the Sakharov Museum and Public Centre, put the support for Putin into the context of fear. When people see that the state is cracking down on human rights again, he argued, they make themselves fit in — go into survival-mode. While rights exist formally in Russia, he explained the practical situation through an old Soviet joke: “Do I have the right? Yes. Can I? No.”

In a weekend of intellectuals discussing how to solve a crisis, novelist and non-fiction writer Slavenka Drakulic gave a sobering lecture on the role of intellectuals in causing crises, specifically the Balkan wars. To be able wage war, to kill, you have to create an enemy and dehumanise it, she argued. Here is where academics, poets, journalists came in handy in former Yugoslavia — by preparing people psychologically for conflict, “using words almost like bullets”.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

And this leads well into the final panel of the conference, on the role of history and memory in politics, the difference between official history and collective and personal memories of the people, and how especially the former can be manipulated. We’re arguably seeing that today already, with Timothy Snyder saying that with events in Ukraine, a European revolution is being contested even as it’s happening. The Russian Ministry of Education is already writing new chapter to explain Crimea, said acclaimed Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov. “And Ukraine might have their version.”

After my trip to Maidan, I asked a Ukraine-based AP journalist what the future might bring for the square. There are only a specific type of people still there, she explained, and they might see how the elections go before they decide to stay or leave.

Or as Myroslav Marynovych, the founder of Amnesty International Ukraine, said during the conference — when there is democracy, there will be no need to go to Maidan.

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

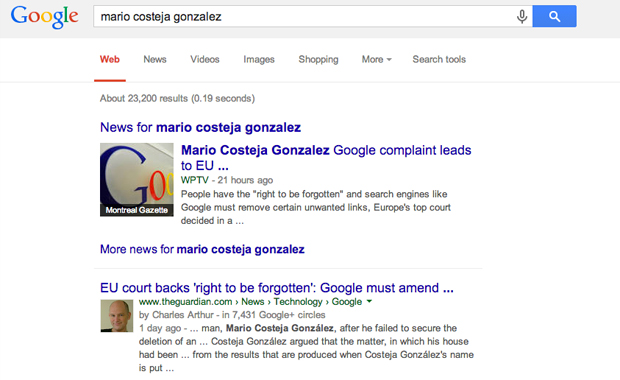

22 May 14 | Counterpoint, Digital Freedom, News and features, United States

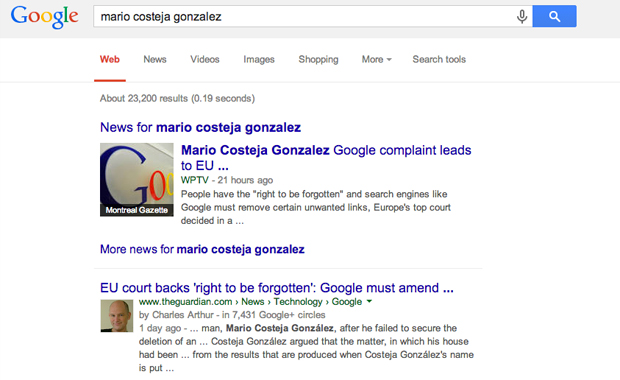

Graham Ginsberg shows how he feels about his search engine profile. (Photo courtesy Graham Ginsberg)

The internet is so much more significant than a newspaper article. It’s bigger than print in its longevity and reach and it’s forever growing, shaping the public lives for all generations, past, present and future.

The handling of this information has become exponentially important. The quote “With great power comes great responsibility” comes to mind. But where is the responsibility when it comes to showing our personalities, our castle, in search engines?

When search engines choose to show information about me, as an example, do they show all available information about me or do they choose certain articles and pictures they consider most relevant and fresh to show the public? And why is there no redress available to me to deal with how search engines portray me?

I recently submitted a complaint to three major search engines requesting that they remove certain pictures and references to articles about me that were old and irrelevant.

Google didn’t respond back, but Bing’s Technical Support did saying, “Thank you for contacting Bing Technical Support regarding your request to remove content from the Bing search engine. Working directly with the site owner or webmaster for removal of the content is the best way to resolve your issue. Bing doesn’t control the operation or design of the websites we index. We also don’t control what these websites publish. As long as the website continues to make the information available on the web, the information will be generally available to others through Bing or other search services.”

But this isn’t entirely true on several levels. But it’s their boilerplate response back, kind of a “it’s not our fault” statement.

Search engines like Bing, Google and Yahoo, do limit and restrict information they show in search results by using software that prioritizes and sorts data into a format it deems suitable.

What is censorship?

Censorship is the act or censoring, the removal or suppression of what is considered morally, politically, or otherwise objectionable. And this is precisely what search engines do right now in their own way using customised algorithms.

Bing suggested that I contact the webmaster in the hope that they would remove the information from being indexed on the internet. Bing suggests that they remove a story as if it never existed. But that isn’t my gripe. I have no problem that our local daily newspaper has pictures and an article about me protesting in front of their establishment. They have every right to have it and I don’t want it removed from their website.

But I have an issue with Bing for showing the information as if it was the only information there was on me. And there is a ton of information about me; from articles I had written to the local paper on a whole bunch of different subjects from national beach access issues to real estate, but little if any is shown in the search results. Just me standing in front of the paper protesting with a noose around my neck, almost ten years ago. Maybe the algorithms looks for keywords like ‘noose’ and prioritizes them higher than say and article about NBA Hall of Famer Larry Bird and his house, which I contributed last year in the same paper.

Because search engines are moneymaking machines, any customized filtering of search results will cost them dearly. And why not, they’re businesses like any other and should be held accountable for their product they’re selling. But what makes search engines different from any other business is they’re so big and powerful and that is why governments need to have means to force them into compliance.

It’s the Wild West all over again. Asking search engines like Google and Bing to police themselves, to be fair and moral has proven to be futile and why should they care or even act accordingly?

To keep the peace for the common good, laws need to have teeth to force offending search engines to comply with logical guidelines that protect the interests of the public and not just interests of these large search engine corporations.

This article was posted on 22 May 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 May 14 | Czech Republic

Peter Demetz (Photo: Prague Book Fair)

Emeritus Yale University professor and author Peter Demetz was awarded the Jiri (George) Theiner prize at the Prague Literary Festival this year.

George’s son Pavel, the prize organiser, said Demetz received the award because “all his life he has remained intellectually honest in his demystification of views which sometimes became popular such as the notion of magical Prague, rather stressing the reality of Czech history, as well as his life-long commitment to Czech literature in American and German environments and as translator of Frantisek Halas´ and Jiri Orten´s poetry”.

Theiner set up the prize in memory of his father’s work, as a former editor of Index on Censorship magazine he brought attention to Czech writing and writers during the communist era. He said: “Almost five years ago I discussed with the director of World of Books (Prague Book Fair), Dana Kalinova, the possibility of making this prize an important permanent fixture at the annual book fair. Looking back I realised that George Theiner´s reputation here was as solid as it was in other countries, despite the fact that he left in 1968.

The jury this year was chaired by Lenka Jungmannova (professor at the Institute of Czech Literature, Academy of Sciences), Martin Putna (literary historian, professor at Prague´s Charles University and critic), Jiri Gruntorad (guardian of the largest samizdat collection in central and eastern Europe, dissident persecuted in the 1970´s and 1980´s) and Ivan Biel (documentary film-maker and lecturer in Film Studies). Next year’s jury was also announced and will include Karel Schwarzenberg (a former Czech foreign minister, one of Havel´s closest aides and supporter of dissidents before 1989 whilst living in Austria), Michal Priban (academic at the Institute of Czech Literature, Academy of Sciences), Vladimír Pistorius (samizdat publisher who successfully made the transition into becoming a ´straight´ book publisher) and Jan Bednar (radio journalist and commentator, signatory of Charter 77, between 1985 and 1992 and who worked for the BBC in London).

Theiner said that they received between 35 and 60 nominations each year from all over the world. The criteria stated that the recipient (or organisation) had made a major long-term contribution to the promotion of Czech literature overseas, with an expectation that they have also made a contribution to freedom of speech and human rights in general. Other prize winners include Andrzej Jagodzinski, translator of Havel, Hrabal, Kundera, journalist as well as a leading member of the democratic opposition on Poland); Ruth Bondy (an Israeli of Czech origin, survivor of Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen who worked as a journalist on the Hebrew daily Davar; and Paul Wilson (a Canadian who lived in Czechoslovakia as a young man before being thrown out in 1977 for collaborating with dissidents and, above all, the band Plastic Pepople of the Universe, translator of Skvorecky, Klima, Havel, Hrabal, radio producer, editor and writer).

Theiner said: “One of the most positive aspects that has come out of the activity surrounding the prize has been the link made between old and new Index on Censorship. It was a real joy to welcome to Prague at the first prize-giving the founding editor Michael Scammell along with some of his old colleagues such as Philip Spender, Haifaa Khalafallah and others. Four years later the present editor Rachael Jolley joined us and moderated a discussion following the award-giving ceremony on freedom after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a reflection on the democratisation of society and freedom of expression in literature and journalism. It´s great to see that the bridge-building that George Theiner was so adept at is still going strong.”

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 May 14 | Academic Freedom, News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster.”

So begins Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter In The Dark, a terse, tragic little book. There’s really not much more I can tell you about it, apart from the fact that the “youthful” mistress is uncomfortably so, Albinus says and thinks some quite sexist things about women, and he ends up disabled (and worse).

Perhaps then, in light of recent requests from English Lit students on American campuses that teachers should provide “trigger warnings” for novels that could contain traumatising themes and scenes, this already revealing opening could be rewritten:

“Once upon a time there lived in Berlin, Germany, a man called Albinus. He was rich, respectable, happy; one day he abandoned his wife for the sake of a youthful mistress; he loved; was not loved; and his life ended in disaster. TRIGGER WARNING: sexism, cis-sexism, borderline paedophilia, violence, ableism.”

Would that be so bad? Clumsy, no doubt, but does it really affect the reader’s experience, or, specifically, the academic learner’s ability to analyse the book? Well, yes, in that it skews one’s expectations, forces one immediately to think “this is a book about misogyny, violence, and disability,” rather than a book about say, the upheaval of interwar Europe, the clash of old and new, or just good old hubris: things Laughter In The Dark are actually about, rather than things that happen in Laughter in the Dark.

The trigger warning has its origins in online forums dedicated to specific topics, and in the backlash against the idea that has happened this week, some commentators have pointed out that this is an imposition by one small community on general society: Jonah Goldberg in the LA Times, for example, unfavourably compared those calling for trigger warnings on campus to Amish people, pointing out that the Amish would prefer not to have to deal with a lot of the modern world, but at least they don’t inflict their desires on other people.

It’s a tempting “who do these people think they are” argument, made all the more so enticing by the intergenerational aspect – pretty much every person I know over the age of 30 finds the “social justice” movement, from which ideas such as trigger warning have sprung from, equal parts infuriating and baffling. It feels like a world of endless taboos and astonishing sincerity, far removed from the heavy irony that, for better or worse, characterised the generation that preceded it.

And they don’t like us much either: writing for Vice last week, Theis Duelund denounced Generation Xers, born between 1965 and 1980, as “slackers [who] nihilistically accept the machine of which they are a part, and can dissect its fundamental facile and evil nature with all the clarity and urgency of a nineteenth-century Romantic poet.”

(If Theis wants to play that game, I’m creeped out by a generation of people for whom dressing up as something out of My Little Pony seems an acceptable subculture for an adult to be involved in).

But changes rarely come from spontaneous mass movements; more often than not, they come from persistent nagging from a minority (or “campaigning” as it’s more kindly called), who eventually convince the rest of us. So to complain that things such as trigger warnings are being foisted upon us by a small group of millennial social justice activists is to avoid the argument about generalised trigger warnings for literature themselves.

The argument being this. Art is an expression of the human condition; our urge to create art, and to consume art, is in large part driven by our need, as social animals, to communicate, to empathise and sympathise.

What that does not mean, however, is that a work of art should, or will, provoke a specific response. Alain De Botton, the writer of philosophically styled self-help books, has recently suggested, through an exhibition he has curated at the Rijksmuseum, that we can use art for self-improvement, implying that specific works inspire specific emotions. It’s a silly, reductive, anti-human argument, implying that there is a correct way to view art, and a correct single message to be taken from it.

Much of the discussion around trigger warnings, and indeed broader discussion of the modern “social justice” movement, is similarly anti-nuance. In the eyes of the online social justice activist, questioning is tantamount to discrimination. This, I believe, is partly generational – asking someone to explain something seems strange to generation just-fucking-Google-it, but as I’ve said, we shouldn’t make age the issue here.

The worry is that in an effort to protect individuals, we risk destroying empathy. The social justice term “allies” has replaced the old fashioned idea of “comrades”. You can support people’s struggle from a distance, “ally” suggests, but you cannot stand with them, because you do not understand the entirety of their experience. It implies a lack of faith in human imagination, in our ability to think outside of ourselves, and in the complexity of the human condition.

So it goes with the trigger warning: there seems little belief here in the idea that a work of fiction could tell us something bigger about the world, could help us understand our fellow beings; or even that reading about experiences that mirror your own may actually help, may make you realise that you are part of something universal. Blood-and-guts fantasy fiction such as Game of Thrones seems to escape opprobrium, perhaps exactly because it’s not seen as being anything to do with the bad things that happen in the real world.

The message and tone of the “trigger warning” suggests a sad lack of faith in the power of art, and, by extension, humanity. We’re capable of better.

This article was posted on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 May 14 | News and features, Politics and Society, Singapore

Roy Ngerng has received a letter from lawyers representing Singapore’s prime minister.

Singaporean blogger Roy Ngerng has become the latest critic of the government to receive a lawyer’s letter.

Through his lawyer Davinder Singh, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong is accusing Ngerng of having made defamatory statements in one of his blog posts. He is demanding that Ngerng take down the post, make an apology and pay him damages. The amount of damages he is asking for is not yet clear.

For critics, commentators and political opponents of the PAP government – the People’s Action Party having been the ruling party in Singapore since 1959 – the threat today is not assassination or getting beaten up by hired thugs, a danger faced by critics and journalists in many other countries. The threat comes instead in the form of lawyer’s letters and lawsuits.

Ngerng’s blog post, entitled “Where your CPF Money is Going: Learning from the City Harvest Trial”, had drawn parallels between Lee, Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC and the management of the Central Provident Fund (CPF, the state pension fund) and the ongoing trial over Singaporean mega-church City Harvest Church’s alleged misappropriation of funds.

He went on to ask questions about the handling of both the state pension and sovereign wealth funds.

“Why have they created such complicated ways that the funds are being channelled, and why do they hide some information that they don’t want Singaporeans to know?” he said to Index on Censorship about his motivation in writing his posts.

The prime minister saw things very differently. “The article means and is understood to mean that Mr Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister of Singapore and Chairman of GIC, is guilty of criminal misappropriation of the monies paid by Singaporeans to the CPF,” wrote Singh in the letter sent to Ngerng. “This is a false and baseless allegation and constitutes a very serious libel against our client, disparages him and impugns his character, credit and integrity.”

If Ngerng does not concede to the prime minister’s demands by Monday at 5pm Singapore time, legal action will be taken against him. He is still talking to his lawyer about steps to take next.

“By eliminating the discourse through a lawsuit I am not able to get more information about [how our CPF is managed],” said Ngerng, adding that he hoped his case would at least further awareness and discussion of the way CPF rules affect Singaporeans.

This is nothing new. British journalist Alan Shadrake was famously taken to court in 2011 for scandalising the judiciary in his book “Once a Jolly Hangman” which examined the use of the death penalty in Singapore. He was found guilty and was jailed for about five weeks before he was deported to the UK.

The socio-political blog Temasek Review Emeritus was threatened with a defamation lawsuit in 2012 for publishing an article that alleged nepotism in the appointment of the prime minister’s wife, Ho Ching, to the chairmanship of Singapore’s other sovereign wealth fund Temasek Holdings. The blog deleted the article and published an apology.

The Attorney-General’s Chambers is also seeking to take legal action against blogger Alex Au for allegedly scandalising the judiciary in two of his blog posts. The court has so far allowed them to take action on only one of the posts, and the AGC is appealing the decision.

Many Singaporeans have objected to the threat of a defamation lawsuit against Ngerng. They argue that even if Ngerng’s assertions had been problematic, the prime minister should have countered them through openness and dialogue rather than a potentially financially ruinous lawsuit.

“The right to freedom of expression is enshrined in our Constitution, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and even in the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration signed by our Government. Yet, our Government’s actions, once again, are highly regressive, and serve to limit the space for expression instead of expanding it,” said human rights organisation MARUAH in a statement.

“Defamation actions do not address the concerns that Singaporeans have. Ngerng’s article, touching on issues like CPF and retirement funding, has sparked important questions that Singaporeans wish to be answered,” said another statement issued and signed by 54 civil society activists and supporters. “The prime minister’s threat of legal action, and the accompanying demand to remove the entire article, will eliminate dialogue and engagement on these questions when they should be debated and rebutted in public.”

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

This story was updated on Friday, May 23, 2014 to reflect an extended deadline for Ngerng to respond. The previous deadline set for response was Friday May 23. The new deadline for a response is Monday, May 26 at 5pm.

21 May 14 | Magazine

Rafal Rohozinski, co-founder of cyber-research thinktank SecDev Group (Photo: Frontline Club)

What is the future of journalism? The innovation report leaked from the New York Times this week highlights the need for change to keep up with fast-moving technology. How do news gatherers and publishers adapt to the volume of online content produced every day? In Syria, the combined duration of wartime YouTube footage now outweighs the realtime number of hours since the conflict began. Rafal Rohozinski, co-founder of cyber-research thinktank SecDev Group, spoke at London’s Frontline Club on Tuesday about redefining news. Here we round-up five of his key points – affecting everyone from readers to citizen journalists to the world’s biggest media organisations.

“Verification is key”

The Boston bombings were one of the most tweeted about events in history, generating seven million tweets – yet 60% were deemed to include false information. We are now swamped with data, but the successful operators will be the ones that know how to interpret it and validate it. “The expert isn’t the algorithm; it’s the human being in the loop,” says Rohozinski. We will see the rise of the “virtual bureau” – which tap into streams of knowledge coming up from the ground, but will be manned by “super journalists”, who understand the local language, politics, way of life etc. These well-trained individuals are able to work their way around both the data and the subject.

“Focus on one platform at your own peril”

Technology is fickle; it will change. “Imagine,” says Rohozinski, “if the BBC had focused only on MySpace.” Twitter is not the one and only route to the truth. Firstly, because it has a bias towards a particular type of user; secondly, because local platforms can often offer as much – or potentially even more – insight. Weibo in China is one example, but little-known localised platforms also exist in Kazakhstan, Tajikistan … Why are they popular? Because they are more accessible (having been developed for a specific group in their native language) and they are often linked to local telecommunications companies, so they are less expensive to access on mobiles. The internet of the future will cut across more platforms and try to link them.

“Syria is the first war being fought in the full glare of cyberspace”

At start of the Syrian war, there were 14 million mobile-phone users (in a population of 20 million). As people have fled, the number of in-country mobile-phone users has grown; there are now 500,000 more. This has done a great deal to empower citizens, but data can also be manipulated. Thousands of seemingly genuine pro-Assad posts – apparently backed up with pictures of houses and children – turned out to be entirely artificial when analysed by an algorithm. It was more subtle than propaganda; it was created to imply an act of discourse among a community. Twitter didn’t pick up that; field reports wouldn’t pick up on that.

“The social contracts that were formed over decades are now completely up in the air.”

News agencies and intelligence agencies are facing the same problems. Both are trying to answer questions that ultimately depend on people. Both are dependent on cyberspace. Do we use metadata? How much do we reveal? How much do we collect? The Snowden revelations have brought a lot of this to light. Biometric data collection is forcing change in social contracts between individuals and state. The rules are grey and undefined. In Syria, doctors are being arrested, because their phones contain details of gun-shot victims. Journalists and intelligence agencies need to look to new ways to protect their sources.

“Facebook and Google have big ambitions, but they are necessarily realities.”

Although Facebook and Google have been buying drone companies to further their reach, Rohozinski predicts complications: “Ultimately, the internet is based on a physical infrastructure of connectivity. When Facebook says they will use their own fibre optic cables so they aren’t subject to control, they are kind of wrong because at some stage the government will step in and say, ‘You are now a telecommunications company, regulation applies.’ Ambitions for becoming common carriers with a physical embodiment, as opposed to simply a virtual overlay, means they will be subject to much more regulation than they have been in the past.”

Rafal Rohozinski co-developed Psiphon, a software application that allows people in closed societies to access censored information. He has worked across the world, including in the former Soviet Union, the Middle East and Africa.

The next issue of Index On Censorship magazine – out in early June – explores citizen journalism and data-tracking in Syria. Subscribe from just £18 per year and find out about hard-hitting journalism under fire around the world.

21 May 14 | Digital Freedom, European Union, News and features, Politics and Society

You can find support for the public’s right to access official information in the strangest places. Like a private EU policy paper draft. As leaked to and published by the whistle-blowers’ website Wikileaks.

The European Union’s Guidelines on Freedom of Expression Online & Offline started with NGO consultations, but the EU’s top working group on human rights (COHOM) wanted the final drafting work done behind closed doors. Wikileaks thought different and released a leaked draft last month.

Designed to set Europe’s agenda for freedom of expression and media rights, the original draft as leaked promised an EU commitment to the right of access to official information of all kinds. But you won’t find the pledge in the final version, as released by the EU in Brussels last week. It’s been cut.

Not one of the nine new priority areas for EU legislation listed in the final version guidelines supports the adoption of right to information legislation. The document also excludes promotion of access to information rights from its list of “Priority Areas of Action”.

The key deleted reference, Paragraph 14 in the version published by Wikileaks, summarised the principle as the “general right of the public to have access to information of public interest, the right of the media to access information and the right of individuals to request and receive information concerning themselves that may affect their individual rights”. These lines were cut in their entirety.

The original text was in line with an emerging European political and legal consensus that the right to receive official information implies that a state has a positive obligation to make that information available to them. The guidelines have been firmly steered in the opposite direction.

In London, experts blame their own government for setting a bad example. The UK government argues that citizens have the freedom, but not the right, to seek and receive information. On that basis it rejects the idea that there is a positive obligation on its officials to make information available to citizens, only that they should have a good reason for not doing so.

“I’d say that the UK government continues to deny that there is a right to information in any form,” says David Banisar of the free expression rights advocacy group Article 19. What’s changed, he says, is that UK courts are beginning to interpret UK common law in the same way as the European Court in favour of the general principle of a right to request and receive official information.

This threatens the legality of the UK’s habit of giving certain officials immunity from Freedom of Information Act requests under UK common law, even where this is incompatible with European law, as the UK Court of Appeal concluded last month, finding that Attorney General Dominic Grieve acted unlawfully by denying public access to Prince Charles’ official letters to government ministers.

In a similar but separate case Times journalist Dominic Kennedy appealed to the courts when the Charity Commission, the agency that monitors charities in the UK, refused his request under the country’s Freedom of Information Act to see paperwork from its inquiry into the management of maverick politician George Galloway’s Mariam Appeal for Iraq. Last month, after seven years’ deliberations, the courts cleared the way for the Commission to hand over the papers – though they have yet to do so, and it may still take a judicial review to make them.

The ruling in favour of the Times in March came with a similar string of citations from European Court (ECHR) cases that are comfortably in line with this new direction for UK common law. “You can ask for information from a public authority just because it is a public authority and it should act in the public benefit.” Kennedy told the UK Press Gazette after his win.

Kennedy’s lawyer Rupert Earle of Bates Wells Braithwaite says that while the ECHR rulings clearly favour openness, the court’s principal chamber has yet to definitively state that public bodies have a default obligation to provide information, subject to the usual provisos on privacy and security. It was, he thought, only a matter of time before it did though.

But even if the ECHR isn’t yet definitive on the issue and the UK courts take their own line, it isn’t a reason to block efforts to mainstream access to information rights in EU free expression policy.

A number of free expression rights groups have expressed dismay. Most were initially consulted on the paper before the EU took drafting behind closed doors. They say the guidelines as they stand not only fail to recognise the right to access to official information, but also that this right is a key element of freedom of expression rights – seriously undermining the guidelines’ effectiveness.

They are calling on the EU to reconsider the guidelines and address these concerns. “We do not believe the (Guidelines on Freedom of Expression Online & Offline) are complete without a clear reference to the right to information and a commitment to priority action in this area,” said the groups in a letter signed May 21, 2014 by nine groups, including Index on Censorship.

The only reason why we know the EU has cut support for reducing official secrecy is thanks to Wikileaks. That irony alone suggests that there should be a few more gates in the wall surrounding the EU’s secret garden of information.

Citizens who wanted more information from their government, the courts and the scores of quangos that influence our lives, would have benefited had the EU guidelines been allowed to recognise the principle that the right to information should be the default start point, limited only when prescribed by law and “necessary and proportionate” to a legitimate aim. The EU needs to put things right.

This article was published on May 21, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 May 14 | Campaigns, European Union

On 12 May 2014, the Council of the European Union adopted the EU Human Rights Guidelines on Freedom of Expression: Online and Offline (Guidelines). The initiative to adopt the Guidelines, which provide “political and operational guidance” to EU staff regarding this important area of EU foreign policy and assistance, is welcome.

At the same time, there are certain problems from the perspective of freedom of expression in the Guidelines. It is, in particular, very problematical that the Guidelines fail to recognise the right of the public to access information held by public authorities as an element of the right to freedom expression and as an operational priority for the EU.

This omission seriously undermines the effectiveness of the Guidelines. The right to access information held by public bodies, or the right to information, has been recognised unequivocally at the international and European level, including by the United Nations Human Rights Committee and the European Court of Human Rights, as well as by regional human rights bodies including the African Union and the Organisation of American States. It is not clear why such an important aspect of the right to freedom of expression – an area in which the EU has been active – should have been entirely left out of the Guidelines.

Paragraph 14 of the Guidelines recognise that, in certain circumstances, human rights outcomes may “be assisted” by the disclosure of information held by the State and that this “can serve to promote justice and reparation”, but they fall short of recognising a right to information. The Guidelines also largely fail to recognise promotion of the right to information as a priority area for action, although paragraph 32 does call for support for the adoption of freedom of information laws.

A further concern is that a document of this importance should have been the subject of an open and meaningful process of consultation before it was finalised. Instead, only limited and essentially internal consultations took place. While internal consultations are an appropriate part of the process, the Guidelines should have been the subject of an open public consultation before being adopted in a final version. At a minimum, this would require a formal draft version of the Guidelines to be posted online, with an opportunity for stakeholders to provide comments.

We do not believe the Guidelines are complete without a clear reference to the right to information and a strong commitment to priority action in this area. We therefore call on the relevant EU actors to reconsider the Guidelines with a view to addressing these concerns. Alternatively, we call on the EU to adopt a dedicated set of guidelines on the promotion of the right to information as an element of freedom of expression.

Signatories:

ARTICLE 19

Centre for Law and Democracy

European Federation of Journalists

Free Press Unlimited

Global Forum for Media Development

Index on Censorship

International Media Support

Internews – Europe

Vivarta

For further information please contact:

Caroline Giraud

GFMD Coordinator

Global Form for Media Development

Email: [email protected]

Mob: +32 477 18 56 01

Office: + 32 2 720 26 00

www.gfmd.info

Twitter: @mediagfmd

Skype ID: coordinator.gfmd

Toby Mendel

Executive Director

Centre for Law and Democracy

[email protected]

+1 902 997-1296

+1 902 431-3688

www.law-democracy.org

Twitter: @law_democracy

Skype ID: toby-mendel

21 May 14 | Counterpoint, Digital Freedom, European Union, News and features

Enshrining the right to be forgotten is a further step towards allowing individuals to take control of their own data, or even monetise it themselves, as we proposed in the Project 2020 white paper (Scenarios for the Future of Cybercrime). The way the law stands in the EU currently, we have legal definitions for a data controller, a data processor and a data subject, an oddity, which lands each of us in the bizarre situation where we are subjects of our own data rather being able to assert any notion of ownership over it. With data ownership comes the right to grant or deny access to that data and to be responsible for its accuracy and integrity.

In response to the ECJ judgement, I have seen a lot of commentators cry “censorship” and make all kinds of unsupportable comparisons with book burning (or pulping), these reactions are misguided and out of all proportion to the decision made. Let’s remember what has been decreed is that an individual has the right to request that certain information be de-indexed from search and aggregation engines. That request is not an order and each one must go through due process and consideration before any changes are made, including if necessary consideration by a court of law. Individuals are not being granted the right to rewrite history, they are being given the right to request, within the strictures of the law, that certain publishers cease to publish information about them which they consider deleterious. They are being given the right to be able to manage their own image online, it seems bizarre that this right is seen by some as the repression of free speech when in effect it gives the individual the right to speak up about something which they find personally damaging.

In 2009, an organisation called “The Consulting Association” was found to be operating a commercial blacklist service to the construction industry. This organisation held detailed files on construction professionals, listing their names, family relationships, newspaper cuttings and details of criminal records. Several global construction companies paid for access to this data and over 3000 individuals were potentially prevented from gaining employment in their industry. Of course this shocks us, and rightly the Information Commissioner took action, seizing the data in question and informing those affected. In many ways a search engine’s constant aggregation of data and even more its contextualisation and publication of that data as relevant to a given name fulfils the same function, now you have a right to at least influence it, even if you cannot stop it.

The ruling is the right one. The court recognises that information that was “legally published” remains so and that the individual has no right to censor it. However, they also recognise that search engines collect, retrieve, record, organise, store and disclose information on an on-going basis and that this constitutes “processing” of data under the EU directive. Further, given that the search engine determines the means and purpose of their own data processing, they are also a “Data Controller” under that directive and again must fulfil the legal requirements of such an entity; any other court decision would weaken that whole directive beyond repair. The entirety of information turned up in response to a search on a person’s name, represents a whole new level of publishing and the discrete items of information would have been very difficult, if not impossible, to put together in the absence of a search engine.

While there will of course be technical and procedural issues that arise from this ruling and there will doubtless be individuals seeking to evade public scrutiny, any other decision on this would have simply blown away the EU Data Protection directive and that is not something any us should be advocating. Consider the wider ramifications of this decision, if a search engine is now a “Data Controller” in the eyes of the law, shouldn’t they be notifying us whenever they collect information about us? Would it be a breath of fresh air if you could begin to understand the wealth of information out there about you and begin to realise an income from it yourself? Personal information is a commodity that commands a financial premium and right now it is others who realise those gains. It’s time we advocated for real ownership of our own data.

Before personal data became a commodity mined by corporations and attackers alike, the need for a legal stance on the identity of the “owner” of data relating to oneself may have seemed laughable. However that has landed us in the situation of today when entities that mine and monetise that same data can refer to this very welcome EU ruling as “disappointing”. Commercially disappointing it may be, however it is a step, albeit a small one, in the right direction.

This article was originally posted on May 13, 2014 at countermeasures.trendmicro.eu

21 May 14 | Digital Freedom, India, News and features, Politics and Society

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Indians, ever a chatty lot, are obsessed with the idea of being obsessed with social media. That is why, as the BJP’s stunning victory in the Indian general elections was declared, the news media immediately began to examine the impact of social media campaigning in the elections. Numbers aside, the victory over social media has revealed the fault lines of Indian society as it stands today.

India’s online population is small as compared to its offline population – about 213 million users to 1.2 billion people – but it is growing. Though these figures expand and contract depending on whom you ask, we do know that 33 million are on Twitter and Facebook has hit the 100 million-user mark. Given these statistics, it is indeed impressive that India’s newest Prime Minister, Narendra Modi has 4.2 million followers on Twitter already. The would-be leader of opposition, Rahul Gandhi, whose party did not win enough seats to actually assume the seat as leader of the opposition in parliament, isn’t on Twitter. However, his party has an account, with about 181,000 followers. There are other political stars on social media, including individual members of various parties, and notably, members of the newly formed Aam Aadmi Party.

However, when asked the question: “who won the social media war” – because, to be sure, there was one – the answer can only really be Narendra Modi. In fact, his own campaign machinery was so well oiled that his personal profile overshadowed his party. “Ab ki baar, Modi Sarkar” (this time, a Modi government) was arguably the catchiest slogan on the campaign and it inspired many a joke, including a takeover of the nursery rhyme – “twinkle, twinkle, little star, ab ki baar, Modi sarkar!” And according to reports, the BJP was mentioned on Twitter, on average, about 30,000 times a day, with the Congress trailing behind at between 15,000-20,000. Modi’s victory tweet promising a better India after election results were declared was retweeted 69,872 times.

Truthfully, there is no way that social media could have supplanted the traditional route. Modi’s tireless campaigning – 437 rallies, 5,827 public interface events across 25 states that is a distance of 300,000km – is impressive. But, equally impressive was the BJP’s entire digital campaign effort; a “social media war room” that reportedly cost Rs 35 lakh (35,000 GBP), with 30 computers and about 50 volunteers, tracking activities across India’s 92,000 villages. And accounts from insiders, young professionals, many whom took sabbaticals from their jobs to participate in this campaign, talks of a breathless environment, where Facebook was used to crowdsource ideas for speeches, and ‘Mission 272’ (in terms of how many seats they were aiming to win) became a reality. In fact, many creative contributions from BJP’s supporters – videos, jingles, songs and poems – can be found on the website.

At the same time, social media has been very revealing about the state of the Indian majority. The tonality of political discourse over the internet, which was very polarized between the Hindu rightwingers and secularists saw vicious language, trolling and hate speech dotting the landscape. However, the Hindu right, abused as communal in the time of the Congress government have emerged victorious and unapologetic about their political leanings. In public groups on Google Plus, cyber Hindus declare that a “pro Hindu lobby is not an option, but a sheer necessity.” In fact, the ‘liberal’ discourse that sweeps much of the mainstream English media was taken aback at the sweeping victory that the BJP has earned in this election. There is nervousness that the BJP, supported and guided by the RSS – Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh—a right-wing, nationalist group espousing strict discipline, martial training and self sacrifice in defence of the Motherland, often derided for being extremist – will work towards a majoritarian agenda where minorities will find less space to exist. These fears are compounded by the RSS’s beliefs – formalized in annual reports – that seek to impose a strict moral code that frowns upon live-in relations, homosexuality and also keeping an eye on minority communities. The RSS has being heartened by educated Indians joining their cause via social media, thereby signaling that their views might no longer be frowned upon as extreme or communal. They do not want to apologize for representing the view of the Hindu right.

And on cue, Narendra Modi, in a rousing speech formally accepting his role as the leader of the majority party in Parliament, promised his fellow BJP MPs that by the birth anniversary of Pandit Deendayal Upadhyaya in 2016, co-founder of the Bharitiya Jan Sangh that later became the BJP as known today, India shall rise to its promise of being a great nation. Tying down his campaign promises to his deep association with the RSS, the signal is clear. Indeed, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the former Prime Minister, had affirmed proudly that “the Sangh is my soul”. The Hindu is back in Hindustan (another name for India).

An analysis in India Today magazine has declared the Indian cybersphere ‘saffron’ (the color associated with the Hindu right) writing, “But their agenda is a mix of post-modern and traditional. They oppose dynasty politics, particularly the Nehru-Gandhi clan and its allies such as Shiv Sena. They call minority appeasement ‘pseudo-secularism’ with such fervour that their sentiment could easily be interpreted as Hindu supremacist or anti-Muslim. They are against lower-caste reservation, particularly because it is poorly implemented. They are concerned about internal security. But above all, they are against corruption.” In deconstructing the ways of the Hindu saffron social media user, the article offers certain clues, such as the words “proud”, “patriot” and “Hindu” appearing in their bios, and often uploading images of Hindu gods as their display picture.

The people have spoken. The media is filled with analysis that people have either embraced Modi for his Hindu leanings, or ignored them in order realize the dream of “development” that is has promised to deliver. The number of Muslim MPs in parliament is down to 21 from 30 in the last session, the lowest number since India’s first elections. The Congress and its allies, who built careers on carefully constructed platforms of secularism – in their first term, they had a Muslim President, Sikh Prime Minister and Christian leader of the party – have been set aside in favour of a openly religious and Hindu BJP. Whatever be the reasons for the vote, for the everyday people tweeting and Facebooking, it appears that being pro-Hindu is slowly being disassociated with being communal. For many, this is a relief.

It seems it might finally be hip to be Hindu.

This article was posted on May 21, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org