10 Apr 14 | Academic Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, Russia, United Kingdom

(Image: /Demotix)

At a conference in Prague last Spring, I listened as the wife of a former diplomat quizzed a Russian journalist on Russian politics. An old Cold War hand, she was keen to discover what motivated Putin and his cadre. Was it some hankering after communism? Was it plain nationalism?

The journalist, displaying the scepticism bordering on cynicism that, ironically, is often found among journalists bravely reporting in monstrous circumstances, shrugged. It would be a mistake, she suggested, to ascribe any value or ideology, even one as meagre as nostalgia, to the current Kremlin. Putin’s regime is about power and money and absolutely nothing else. There is no Putinism. There is just gangsterism.

It’s probably worth keeping this in mind while we fret over the geopolitics of Putin’s Crimean Anschluss. Indeed more than that, it’s clearly a point of view that merits more study. Unfortunately, one recent study of Putin’s gangster tendencies has been suppressed: not by the Kremlin, but by a UK academic publisher living in fear of England’s libel laws.

Karen Dawisha, Director of Miami University’s Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies, was set to publish a book on Putin’s gangster connections. One hesitates to use the dread stock book review phrase “timely and relevant”, but in this case it seems difficult to avoid it. The proposed subtitle “How, why and when did Putin decide to build a Kleptocratic and Authoritarian Regime in Russia and what is its Future?” gives a pretty good impression of what the book would contain.

According to Ed Lucas at the Economist, Dawisha’s publishers, Cambridge University Press, has taken fright at the prospect of a book actually investigating gangsterism among Putin and his cronies, and decided it will not publish the book.

In a letter to Dawisha, published by the Economist, John Haslam of CUP noted:

“After discussion with legal colleagues who have reviewed the typescript from both a US and UK legal perspective, I’m afraid that our view is that we are not in a position to proceed with your book. The decision has nothing to do with the quality of your research or your scholarly credibility. It is simply a question of risk tolerance in light of our limited resources.”

Haslam goes on:

“We have no reason to doubt the veracity of what you say, but we believe the risk is high that those implicated in the premise of the book—that Putin has a close circle of criminal oligarchs at his disposal and has spent his career cultivating this circle—would be motivated to sue and could afford to do so. Even if the Press was ultimately successful in defending such a lawsuit, the disruption and expense would be more than we could afford, given our charitable and academic mission.”

This is depressing reading, and sadly familiar.

Six and a half years ago, Cambridge University Press was faced with a similar problem, and reacted in a similar fashion, i.e. capitulation.

Back then, publishers’ dreams were tormented not by Russian gangsters but Saudi bankers. Sheikh Khalid Bin Mahfouz was the scourge of Fleet Street’s inhouse legal teams. The Saudi, who had bought Irish citizenship from kleptocrat Taoiseach Charles Haughey, was notorious for issuing threats and writs to any publication or publisher that so much as mentioned him – particularly when it came to suggestions that he may have been linked, either personally or financially, to Osama Bin Laden.

Everyone I mentioned in that last paragraph is dead now, by the way, which is why I feel no qualms about writing about any of them.

When Index first wrote about Bin Mahfouz there were many, many fraught discussions and even arguments about how to proceed. That’s a big part of what campaigners, lawyers and hacks mean when they talk about the “chilling effect” of defamation laws. The knowledge of working on something that could be ruinuous not just personally, but for an entire publication, can make you queasy and put your colleagues on edge. The fact that Bin Mahfouz, worth over $3.2 billion dollars, could have tied up even the biggest publications in endless, expensive litigation tended to put people off. Even when people did publish, in the end they always backed down in the face of the Sheikh’s muscle. His personal website featured an entire section dedicated to apologies hastily issued by terrified newspaper legal departments after Bin Mahfouz threatened them with a trip to the High Court.

Anyway, in 2007, CUP were about to publish a book on funding for Islamist terror, called Alms For Jihad. Bin Mahfouz got wind of it, and issued the usual threats via his lawyers, Kendall Freeman. CUP apparently jumped through a few hoops, asking the book’s American authors, Robert O Collins and J Millard Burr to compile a letter countering the claims in bin Mahfouz’s book. But in the end they pulped the book and recalled library copies. It was a low point, but in a curious way, some good came out of it. The Alms For Jihad case was among those that highlighted the serious problems with English defamation law. Not long after the pulping of Alms For Jihad, the first stirrings of the Libel Reform Campaign began. On 1 January 2014, a new defamation law came into force.

So why are we seeing a repeat of the Alms For Jihad debacle with this book on Putin and his cronies?

The new law should make it harder for foreign litigants to sue in London, and it should make them prove that they have suffered genuine damage. Without having seen the contents of the book (CUP say there is no reason to doubt the veracity of Dawisha’s claims about Putin’s circle, while simultaneously refusing to stand by their author), one would imagine that, particularly given US and European moves against Putin’s inner circle, the book would have had a decent chance in court.

But the new law will need to be tested. It may be that while the legal barrier to putting up a spirited defence of free speech in court has been considerably lowered, the mental block remains for many publishers. Only a strong early ruling under the new law will shake this off.

But who’s going have the first go?

This article was published on April 10, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

10 Apr 14 | Bangladesh, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Reports, News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Bangladesh witnessed the internet take on an increasing role in its socio-political sphere in 2013. Usage trends swung more toward heart-warming positives, in contrast to the country’s regulatory precedents, which despite policymakers facilitating net use via cheaper connections and better infrastructure, have been mostly negative. Common people felt empowered using the internet.

Last February, tens of thousands of people were gathered, inspired by blog posts and social media to protest for the first time in the country’s history. At the same time, religious zealots started attacking online activists, and policymakers initiated the use of a draconian ICT (information and communication technology) act to clamp down on opposition, thus threatening digital freedom of expression overall.

Internet usage, mobile telephony penetration, and other ICT-enabled applications have been enjoying steady growth in both Bangladesh’s private and public sectors for over a decade. The present political leadership came to power with a mandate to “digitise” the country by implementing its Digital Bangladesh by 2021 vision. This policy rolled out net enabled ICT centers to ensure easier access of information for its citizens all over Bangladesh. At present, the national teledensity is at over 70%. Around 20% of the population use the internet, of which 90% go online using mobile phone services. There are around 200,000 local bloggers based in Bangladesh, who alongside millions of Bangladeshi Facebook users were until recently enjoying near-uninhibited freedom to express their thoughts online.

The true power of social media to mobilise massive groups of people on a political issue was first observed in Bangladesh during the Shahbag movement in February 2013. Like the 2011 uprising in Egypt’s Tahrir Square, protesters gathered for several weeks in the Shahbag intersection of Dhaka University campus, demanding justice against known war criminals of its liberation war in 1971. This movement was initiated by local bloggers and social network users, and flourished with their help. People were using online media freely to organise in the real world and to create spaces for net based dialogue on critical issues. However, along with such freedom came confrontation. Shahbag made public the conflict between the ultra religious, anti-establishment elements and the moderate, mainstream and secular netizens. One pro-Shahbag blogger was killed, many other online activists were threatened with physically harm by the zealots. Suddenly an online inspired mass protest, which was enjoying complete freedom of expression in the digital space, turned out to be the root cause of a messy and prolonged offline affair.

The Shahbag movement exposed the major weaknesses of the local legal system, responsible for guaranteeing its citizens’ freedom of expression. The government turned out to be confused in their decision making process and tried to appease both sides. It first banned several ultra-religious sites. Then the law enforcement agency arrested four secular Shahbag bloggers and organisers, charging them with “harming religious sentiments”. Such actions sent out confusing signals to the general population and posed serious questions on the existence of any tangible legal safety net for online communication in Bangladesh.

In fact, the government’s performance in the digital space has been consistently disappointing between 2012 and 2013. In addition to its self-conflicting stance on Shahbag, it applied a heavy-handed approach in dealing with other web services throughout the year. YouTube was banned for months (September 2012 to May 2013) due to The Innocence of Muslims, which ignited major protests in Bangladesh. Additionally, Facebook was blocked on several occasions, from periods of a few hours to days at a stretch. Freedom House included Bangladesh for the first time in its yearly Freedom On the Net report in 2013. Based on its performance in 2012 and first half of 2013, the internet in Bangladesh was found to be partially free, enjoying a relatively better online environment in comparison with its South Asian peers, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Nevertheless the situation is getting worse. Indiscriminate applications of the ICT Act 2006, a rise of online hate speech and related crimes have left net users in Bangladesh insecure.

In 2013, the government started using the ICT Act of 2006 more frequently, mainly to address issues related to online space and freedom of expression. This act was formulated in early 2000 and according to many legal experts, it was due to be amended to become more user-friendly and inclusive. The Bangladeshi government did amend it in August 2013, but unfortunately made it more repressive and inflexible. The newly amended act provisions a maximum 10 years in prison and fines up to £74,555 for any offensive religious, social, or political expression made online. It moreover made arrests under this act non-bailable and the police were given the power to arrest people without a warrant. Instead of strengthening the legal system to protect peoples’ right to communicate freely online, this act tightened its grip on peoples’ freedom of communication. A series of arrests took place and several court cases were filed under the act in 2013. Besides the bloggers, editors and journalists of two newspapers, two NGO officials, and several other people were arrested, some of whom are close to opposition party politics. One university teacher was sentenced to seven years in prison under the act for threatening to kill the prime minister through a Facebook status.

Overall, the present state of affair of net freedom in Bangladesh is very uncertain. There has been no independent regulatory or legal body put in place to protect the rights of the people online. Civil society needs to be more active to thwart any digital policing that compromises public freedom. As the challenges related to ICT access in Bangladesh are being solved fast, it is now high time to make sure that its citizens enjoy true freedom while using such digital infrastructure.

This article was posted on 10 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

09 Apr 14 | Events

09 Apr 14 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

Since Mohamed Morsi’s ouster in July 2013, backed by the army and General Abdel Fattah al-Sis, there has been a rise in the number of arrests of people based on their sexual orientation (Image: Adham Khorshed/Demotix)

A Cairo misdemeanour court on Monday sentenced three men to eight years in prison “for committing homosexual acts”. A fourth defendant in the case was sentenced to three years in prison with hard labour.

The men were allegedly found dressed in women’s clothes and wearing make-up when they were arrested last month, following a police raid on a private apartment in Cairo’s northern residential suburb of Nasr city. The apartment had been a meeting place for some members of Egypt’s gay community, who had been attending a party there when the raid occurred.

During Monday’s court session, prosecutors said one of the defendants had rented the apartment to receive “sexual deviants” in his home and host parties for them. While there are no laws banning homosexuality in Egypt, “debauchery” or breaking the country’s law of public morals is outlawed. Egyptian courts use legislation on debauchery to prosecute gay people on charges of “contempt of religion” and “sexual immorality”.

The severe sentences the four men received on Monday have raised concerns among rights campaigners of a widening crackdown on Egypt’s long-oppressed and marginalised gay community. Youth-activists expressed their dismay and disappointment at the verdicts on social media networks. In a message posted on her Twitter account on Tuesday, Shadi Rahimi, a journalist and photographer working for Al Monitor described the verdicts as “outrageous”. Blogger Nervana Mahmoud meanwhile said: “The verdicts demonstrate that the current regime is as conservative as their Islamist predecessors.”

In Egypt’s conservative, predominantly Muslim society, homophobia is deeply embedded, with 95% of Egyptians sharing the conviction that “homosexuality should not be accepted”, according to a 2013 poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre.

The recent crackdown on Egypt’s gay community is highly reminiscent of the security clampdown in the spring/summer of 2001 when authoritarian president Hosni Mubarak was still in power. In May 2001, 52 people suspected of being gay were arrested on charges of immorality during a raid on a tourist boat moored on the Nile in Cairo. Twenty three of the men were sentenced to up to five years in prison with hard labour. The highly-publicised “Queen Boat case”, named after the discotheque-boat that for long had been a known meeting place for Egypt’s gay community, signalled what rights campaigners feared might be an end to long years of discreet and quietly tolerated public activity by the country’s threatened LGBT population. Some analysts said at the time that the sudden crackdown was a means of diverting attention away from the regime’s failures, including a political crisis and a looming economic recession. Critics of the 2001 crackdown also believed it was an attempt by the then-autocratic regime to present an image as “the guardian of public virtue so as to deflate an Islamist opposition movement that appeared to be gaining support every day”.

Not surprisingly, many of Egypt’s gay men and women were at the heart of the January 2011 protests demanding democracy, freedom and social justice. They had hoped that the revolution would usher in a new era of change including greater freedoms and tolerance, allowing them to better integrate into mainstream society. Karim, who requested that only his first name be used out of concern for his safety, told Index: “We had a lot of hope then but the last three years have only brought disappointment. There has been no change in people’s attitudes. In fact, we get insulted more often now, as people feel emboldened knowing that the authorities are siding with them.”

Rights campaigners agree that life has gotten worse for Egypt’s gay citizens since the Arab Spring. Adel Ramadan, a legal officer at the Cairo-based Egypt Initiative for Personal Rights told NBC News last year that “after the fall of Mubarak, the criticism of revolutionary groups has always contained a sexual element. Women who participate in protests are often called prostitutes or ‘loose’ women, while male revolutionary activists are called homosexuals”.

Meanwhile, the rise of Islamists to power in Egypt in the post-revolution era fuelled fears among rights groups and Egyptian gay citizens over greater restrictions on the gay community. They anticipated an even harder crackdown under Islamist rule and worried that the Islamist-dominated parliament would pass anti-gay legislation. Whether or not their fears were justified is uncertain, for Islamist rule in Egypt was short lived, lasting only one year. President Morsi was toppled by military-backed protests on July 3, 2013 and the People’s Assembly (the lower house of Parliament responsible for issuing legislation) was disbanded by a Supreme Constitutional Court ruling in June 2012, only a few months after its members were elected. However, in their time in power, there were signs indicating a potential tightening of restrictions on Egypt’s gays. In August 2012, a man was arrested for allegedly leading a “gay sex network” while later that year, vigilantes beat four men suspected of being gay before handing them over to the police.

“Many of my gay friends fled the country when the Islamists came to power; they were terrified of what would happen to them under Islamist rule. They knew they would not be able to live freely so they emigrated,” said Karim. “Those who stayed behind, participated in the 30 June mass protests demanding Morsi’s downfall. We were overjoyed when he was toppled and hoped there would be fewer restrictions on us from then on,” he added.

Paradoxically, since Morsi’s ouster in July 2013, there has been a rise in the number of arrests of people based on their sexual orientation, according to the US-based Human Rights First group. The group says the surge in arrests and prosecution of gay men and women is part of the military-backed regime’s efforts to reassure Egyptians that the current regime is as conservative as any Islamist party.

In October 2013, state-owned Akhbar el Youm reported that at least 14 men were arrested for “practicing homosexuality” after a raid on a health club in El Marg district in northeastern Cairo. According to the weekly newspaper, police found the men “in positions that were against religious precepts”. Less than three weeks later, police arrested ten more people on “homosexual-related charges”. The arrests occurred during a police raid on a private party held to celebrate Love Day (Egypt’s equivalent of Valentine’s Day) in Cairo’s western suburb of 6 October. The men were subjected to humiliating anal examinations before being convicted of prostitution and sentenced to between three and nine years in prison. Mohamed Bakier, one of the defence lawyers in the case, said the charges against them were “political rather than criminal”. He added that the harsh sentences they received were meant to deliver a message that the society is still conservative.

Similarly, the severe sentences handed down to the four men on Monday may be an attempt by the military-backed authorities to appease a sceptical public and win over conservatives in the deeply polarised society ahead of upcoming presidential elections in which the former defence minister Abdel Fattah El Sisi is the lead contender.

The verdicts, meanwhile, coincided with another court ruling upholding three-year jail terms imposed on three secular revolutionary activists convicted of organising or participating in unauthorised protests, prompting rights campaigners to concur in opinion that this is all part of the wider, ongoing crackdown on personal freedoms.

Whatever the motives are behind the harsh sentences, one thing is certain: The verdicts have increased anxiety over the insecurity of Egypt’s vulnerable gay community. “We no longer feel safe,” said Karim. “We know we are being targeted by the police and sooner or later, they will come after us.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the 52 Egyptians were arrested in May 2010. The incident took place in May 2001.

This article was posted on 9 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

09 Apr 14 | Digital Freedom, European Union, News and features

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Retaining data is the reflex of a functioning bureaucracy. What is stored, how it is stored, and when it is disseminated, poses the great trinity of management. These principles lurk, ostensibly at least, under an umbrella of privacy. The European Union puts much stake in Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, stressing the values of privacy that covers home, family and correspondence. But there are also wide qualifications – interferences are warranted in the interest of national security and public safety, allowing Member States, and the EU, a degree of room to gnaw away at privacy rights.

That entitlement to privacy has gradually diminished in favour of the “security” limb of Article 8. The surveillance narrative is shaping privacy as a necessarily circumscribed right. The realm of monitoring and surveillance is being extended. Technologies have proliferated; laws have remained, if not stagnant, then ineffective.

Unfortunately for those occasionally oblivious drafters of rules in Brussels, the judges of the Court of Justice of the EU did not take kindly to the Data Retention Directive, which requires telecommunications and internet providers to retain traffic and location data. That is not all – the directive itself also retains data identifying the user or subscriber, a true stab against privacy proponents keen on principles of anonymising users.

The objective of the DRD, like so many matters concerned with bureaucratic ordering, is procedural: to harmonise regimes of data retention across various member states. More specifically, Directive 2006/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of March 15 2006 deals with “retention of data generated or processed in connection with the provision of publicly available electronic communications services or of public communications networks”.

Other courts have expressed concern with the directive, which propelled the hearings to the ECJ. These arose from separate complaints in Ireland and Austria over measures taken by citizens and parties against the authorities. The Irish case began with a challenge by Digital Rights Ireland in 2006. The Austrian legal challenge was pushed by the Kärntner Landesregierung (Government of the Province of Carinthia) and numerous other concerned parties to annul the local legislation incorporating the directive into Austrian law.

The Constitutional Court of Austria and the High Court of Ireland shook their judicial fingers with rigour against it – the judges were not pleased. The disquiet continued to their brethren on the ECJ, which proceeded to make its stance on the scope of the retention law clear by declaring it invalid. EU officials should have seen it coming – in December last year, the Advocate General of the ECJ was already of the opinion that the DRD constituted “a serious interference with the privacy of those individuals” and a “permanent threat throughout the data retention period to the right of citizens of the Union to confidentiality in their private lives.”

The defensive stance taken by the authorities is so old it is gathering dust. Technology changes, but government rationales never do. Invariably, it is two pronged. The ever pressing concerns of security forms the first. The second: that such behaviour does not violate privacy – at least disproportionately. You will find these principles operating in tandem in each defence on the part of authorities keen to justify extensive data retention. Such intrusive measures have as their object the gathering of information, rather than the gathering of useful data. The usefulness is almost never evaluated as a criterion of extending the law. Instinct, not evidence, is what counts.

The rationale of the first premise is simple enough: information, or data, is needed to fight the shady forces of crime and terrorism. Better data retention practices equates to more solid defence against threats to public security. The ECJ acknowledged the reason as cogent enough – that data retention “genuinely satisfies an objective of general interest, namely, the fight against serious crime and, ultimately, serious security.” The authorities were also keen to emphasise that such a regime of retention was not “such as to adversely affect the essence of the fundamental rights to respect for private life and to the protection of private data.”

In dismissing the main arguments of the authorities, the points of the court are clear. In retaining the data, it is possible to “know the identity of the person with whom a subscriber or registered user has communicated and by what means”. Identification of the time of the communication and place form which that communication took place is also possible. Finally, the “frequency of the communications of the subscriber or registered user with certain persons during a given period” is also disclosed. Taken as a whole set, these composites provide “very precise information on the private lives of the persons whose data are retained, such as the habits of everyday life, permanent or temporary places of residence, daily or other movements, activities carried out, social relationships and the social environments frequented.” Former Stasi employees would be swooning.

The judgment provides a relentless battering of a directive that should never left the drafter’s desk. “The Court takes the view that, by requiring retention of those data and by allowing competent national authorities to access those data, the directive interfered in a particularly serious manner with the fundamental rights to respect for private life and to the protection of personal data.”

The laws of privacy tend to focus on specificity and limits. If there is to be interference, it should be proportionate. The directive had failed at the most vital hurdle – if privacy is to be interfered with, do so in even measure with minimal interference. The DRD had, in effect “exceeded the limits imposed by compliance with the principle of proportionality.” The decision is unlikely to kill off regimes of massive data retention – it will simply have to make those favouring surveillance over privacy more cunning.

This article was posted on April 9, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

09 Apr 14 | News and features, Pakistan, Politics and Society

(Image: Aleksandar Mijatovic/Shutterstock)

In the sixth attack on Express Media employees unknown assailants threw a hand grenade at the gate of Express News bureau chief’s house in Peshawar’s Murshidabad area. Though no one was injured in Sunday’s incident, it highlights the dangers for Pakistan’s journalists.

“It was 6:30 am. I woke up to a loud screeching made by a motorbike, followed seconds later by a thunderous sound. I ran out and saw a cloud of smoke,” said 38-year old Jamshed Baghwan, speaking to Index over phone from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s provincial capital, Peshawar.

The main gate and the walls of neighbouring houses, said the journalist, were pocked with holes made by ball bearings packed in bomb.

This was the second attack on Baghwan. On March 19, he had found a 2 kg bomb “at exactly the same place” which was diffused in time by the bomb disposal unit.

“I have no idea why anyone would attack me,” he said. “I’ve covered the army operation in Swat when the security forces cleansed the place of militants; I’ve covered conflicts in Bajaur and South Waziristan, but there never was a threat from any quarter, so why now?” he is perplexed.

This is the sixth attack on Express Media organisation in the last nine months. Four of Express’s employees have been killed.

On March 28, a senior Pakistani analyst, Raza Rumi, working for Express News, came under a volley of gunshots after his car was intercepted by gunmen on motorbikes, while passing a busy market place in Lahore. He has been vocal in his condemnation of the Taliban and religious extremist groups. While Rumi narrowly escaped, his driver died and his guard remains critically injured.

An editorial, by Express Tribune, a sister organisation, had frustration and helplessness written all over when it read: “Shall we just close shop, keeping in mind that we are no longer safe telling the truth and the state clearly cannot, or may not want to, provide us protection or even justice?”

The same day as the attack on Baghwan, in the eastern city of Lahore, in the Punjab province, a rally was held by journalists and civil society to protest the death threats on Imtiaz Alam, secretary general of South Asia Free Media Association.

Political leaders and the government routinely condemn attacks on media workers, but have yet to take concrete action. In the meantime, journalists continue to die. Declan Walsh of the New York Times tweeted: “When militants take on journalists, this is how it goes – one by one, they pick them off. Outrage is not enough.”

With no let up in the attacks, journalists are saying they need to watch their own as well as their colleagues’ backs.

But is it possible when journalists have yet to come together?

Kamal Siddiqi, editor the Express Tribune lamented: “…there is no unity amongst the journalist community. We have a great tradition of abiding by democratic traditions but at the same time we have done poorly in terms of sticking together. There are splinters within splinters,” he wrote in his paper.

However, media analyst Adnan Rehmat, finds solidarity and sympathy for those who have been attacked or are under threat among the journalists. “It’s the media owners who are not forthcoming. The pattern and nature of attacks is consistent; but not the response from media owners,” he says.

He recently published a book titled Reporting Under Threat. It is an “intimate look into the harsh every-day life of journalists working in hostile conditions” through testimonies from 57 Pakistani journalists, including editors, reporters, camerapersons, sub-editors, news directors, photographers, correspondents and stringers working for TV channels, newspapers, radio stations and magazines.

“They don’t consider the attack on one individual an attack on all,” he points out. “While Rumi’s attack elicited a strong reaction from civil society, there was little condemnation from media houses. On the other hand, because Alam does not work for any competing newspaper or channel, it was easier to support him and this was across the board.” Part of the problem, said Rehmat was the media owners were not journalists and therefore did not equate themselves with journalists.

Rehmat believes, it is time, the media owners gathered on platforms like the All Pakistan Newspapers Society, Pakistan Broadcaster’s Association (representing private TV channels) and the Council of Pakistan Newspaper Editors and come up with a “singular response” in the form of policies that reflect that “safety of journalists is their number one priority”.

“I think the media owners are playing into the hands of the militants,” pointed out Shamsul Islam Naz, former secretary general of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists. “If this is a dangerous business, why hasn’t a single media owner been killed yet?” He said he had been observing the way private news channels had been covering militancy and giving unsolicited air time to banned militant outfits infraction of Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority.

Ironically, these attacks follow a high level meeting of Committee to Protect Journalists delegation with prime minister Nawaz Sharif in which the latter had pledged to address the threats to country’s journalists. Among the several commitments, was putting protection of journalists on the agenda in the ongoing peace talks with the Taliban.

According to CPJ, since 1992, 54 journalists have been killed with their motives confirmed, meaning CPJ is reasonably certain that the journalist was killed in line of duty.

While militants openly admit to the attacks, this is not the only threat to journalists. There are state elements including its intelligence agencies, members of elected political parties, even those from the business community, who may go from simply roughing up, torturing, detaining, to even killing if the dissenting voices get relentless and refuse to keep quiet.

This article was posted on 9 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

08 Apr 14 | About Index, Campaigns, Press Releases

A NEW CHAMPION FOR FREE EXPRESSION

Index announces new CEO

Index on Censorship, the organization that advocates for freedom of expression and against censorship throughout the world, is delighted to announce the appointment of our new Chief Executive Officer, Jodie Ginsberg.

Jodie, who takes up her post next month (mid-May), comes from the think-tank, Demos. A former London Bureau Chief for Reuters, Jodie worked for more than a decade as a foreign correspondent and business journalist. She was previously Head of Communications for Camfed, a non-profit organisation working in girls’ education.

The Chair of Index, David Aaronovitch, said; “Index is an indispensible organization and I am really pleased to have someone of Jodie’s experience and talents coming to us. Index’s work defending freedom of expression on- and off-line is more important than ever in the face of growing censorship in many countries around the world from Turkey to Russia, from Azerbaijan to India to China. I am sure Jodie will build on the great work of her predecessor Kirsty Hughes and all the Index staff, and lead Index into new and important campaigns.”

Jodie Ginsberg said: “Defending freedom of expression is not an easy task but it is a vital one. If we want to live in a world where everyone is free to speak, write, publish or perform without fear of persecution then we need to champion those rights every day. I’m thrilled to be leading an organisation with such an amazing track record in defending free expression and can’t wait to start working with our incredible roster of supporters and contributors.”

Outgoing CEO, Kirsty Hughes, said: “I am delighted that Jodie will lead Index in its vital campaigning work around the world. I wish her all success in this vital and exciting challenge.”

Press enquiries to [email protected]

08 Apr 14 | Australia, News and features, Politics and Society

Disillusioned with the Abbott government’s agenda, protestors took to the streets of Brisbane on March 16, 2014. The rally was staged as a vote of no confidence in policy that some say goes against principles of humanity, decency, fairness social justice and equity. (Photo: Claudia Baxter / Demotix)

Australia is looking at repealing sections of the Racial Discrimination Act. Though the move has long been mooted by the government of prime minister Tony Abbott, recent moves to repeal parts of it–and specifically section 18C–has sparked public debate and anger on both sides of the political divide.

“People do have a right to be bigots you know,” attorney general George Brandis told the Australian Senate in late March. He was referring to the Abbott government’s repealing of section 18c of the Racial Discrimination Act which makes it unlawful to “offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate” people based upon their race.

Called by some the “Bolt clause” the repeal of this section has caused both outcry and debate. Conservatives, for the most part, applaud the action for reasons of freedom of speech. Others argue it sets a dangerous precedent and will allow more hate speech to go unchecked or unpunished. It also sends a wider message that racism is acceptable, critics argue.

The Abbott government’s stance can be traced back to 2011. News Limited columnist Andrew Bolt, who is one of the country’s best known conservatives, was found guilty by a federal judge of breaching the Racial Discrimination Act. Writing in Melbourne daily the Herald Sun in 2009 Bolt suggested in two stories that light skinned indigenous people claimed Aboriginality for their own gain. A federal judge found that the articles had not been written in good faith and would offend a reasonable member of the Aboriginal community. Bolt had argued his articles fell within the laws of free speech provisions and, after the ruling was handed down, called it “a terrible day for freedom of speech in this country.”

“In good faith” is important to note as the Racial Discrimination Act’s 18D stipulates that comments made in good faith are permissible as are expressions of genuine belief. Sections D, B and E will also be repealed, however. In their place it will be unlawful to vilify or intimidate persons based upon their race; however, “to intimidate means to cause fear of physical harm.” The new exemption is rather more broad: “This section does not apply to words, sounds, images or writing spoken, broadcast, published or otherwise communicated in the course of participating in the public discussion of any political, social, cultural, religious, artistic, academic or scientific matter.”

Section 18c does not actually carry a criminal penalty. It became law in 1995, partly through recommendations made by the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody

In a March 12 editorial the Herald Sun pointed out that the government should not be there to adjudicate in cases where offense has been caused and “is to diminish people’s right to voice their opinions, blunt as they might be.” The paper pointed out that defamation laws–incidentally far more commonly used in Australia than any invocation of 18C–are generally more useful in determining if harm has been caused. Bolt has previously been sued for defamation by a Victorian judge.

Brandis has said he is a proponent of free speech and against the kind of internet filtering suggested previously under Labor whereby sites that were refused classification were simply blocked. Many of the sites–in a list published by Wikileaks–contained material that might have possibly been objectionable but was not illegal. As previously reported by Index, Brandis established a “Freedom Commissioner” in Tim Wilson in late 2013. Wilson has been a strong critic of the Australian Human Rights Commission, suggesting it had narrowed its horizons and focused more upon racial discrimination than freedom of speech. Before being appointed to the commission he attacked it for its silence on the previous Labor government’s new media regulations. Wilson made clear last year at the time of his appointment that would support repealing of 18C.

Though publicly committed to free speech Abbott has previously criticised national broadcaster ABC for its reporting of alleged abuse of refugees by the Australian Navy and its reporting of Australia’s tapping of Indonesian Prime Minister Yudhoyono’s wife’s phone, though under the previous administration, “a lot of people feel at the moment that the ABC instinctively takes everyone’s side but Australia’s.”

Though the coalition has lionised the restorative powers of a free press upon a free society, one of its own MPs, Ken Wyatt, has threatened to cross the floor on this issue, while according to the Sydney Morning Herald, MPs David Coleman and Craig Laundy had also expressed concern. Crossing the floor is, though permissible, a rarity dangerous to one’s political career.

Labor Senator Penny Wong and Leader of the Opposition in the Senate suggested that those arguing against 18C are viewing things in terms of “an abstract philosophical or legal argument… it’s a debate about words and principles…For people who have experienced racism… it’s actually a debate about real people and real hurt.”

This article was posted on 8 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

07 Apr 14 | Europe and Central Asia, Greece, News and features

Thessaloniki Pride parade 2012 (Image: Konstantinos Tsakalidis/Demotix)

There is a “dictatorship of the gay minority” and gay people should be “treated” by members of Golden Dawn. These are only excerpts of a 15-minute homophobic rant by journalist Dimos Verikios during a recent episode of his daily show on Alpha radio station. The outburst was met with a number of complaints and social media outrage, and has been condemned by the Journalists’ Union of Athens Daily Newspapers.

Verikios was targeting gay writer Auguste Corteau, who revealed his sexuality by publicly stating that he won’t be joining new political party The River, preferring to stay loyal to his husband and his books. In response to this, the radio host among other things said: “That’s why society goes to hell. Being gay today and crying it out loud is considered a cunning behaviour and not a problem.”

Verykios’ outburst seems to be only the tip of the iceberg. Homophobic stereotypes and discrimination based on sexual orientation is widespread in Greece, both on state level and in wider society. The 2013 annual report by the European arm of the international gay right organisation ILGA, reports a wave of violence directed at the LGBTI community by extremists, ranking Greece 25th out of 49 European countries for gay rights. In 2012, European Commission against Racism and Intolerance urged Greek authorities to raise awareness “on the implementation of the principle of equal treatment regardless of racial or ethnic origin, religious or other beliefs, disability, age or sexual orientation”.

The extension of legislation (institution of civil partnership) to same sex couples has “frozen” because of continuing pressures from the Greek Orthodox Church, while at the same time the country has been found violating the European Convention of Human Rights. Index has previously reported on homophobic behaviour and attacks by Golden Dawn and its supporters. Firstly, regarding the persecution of people involved in the play “Corpus Christi” and secondly, regarding the mockery of journalist Tasos Theodoropoulos by the far-right publication called “Stohos”, and the subsequent attack on him.

Electra Leda Koutra is the president of the NGO Hellenic Action for Human Rights and lawyer for the Greek Transgender Support Association. She was harassed by policemen and illegally detained for a short while last June for trying to communicate with her transgender client. “Many cases do not reach the courts because of the ‘outing’ that the victims would have to unwillingly go through during the legal procedure,” she explains to Index, adding that many of these cases often go unresolved.

Verykios outburst was answered by a collective complaint from the LGBTQI community — nearly 20 organisations and collectivities took part — to the National Council for Radio and Television (ESR). The president of ESR, Ioannis Laskaridis, said told media that the volume of complaints filed was “unusual”.

Corteau is suing Verykios over the statements, posting on his Facebook page that: “I have decided that I have a duty to stand up for and protect the people I love and then any person that could find themselves in my position, a target of the poisonous language represented by Mr Verikios.” Corteau’s lawyer Christos Gramatidis explained the nature of the legal action to Index: “It is the first lawsuit of its kind (compensation for moral damages, eponymous opposing parties) based on the basis of attacking personality and consisting of libel and insult of gender identity. As a country we haven’t incorporated yet the European legal framework of combating intolerance”.

Gramatidis added: “There are so many people from the LGBTI community who accept bullying in schools and elsewhere in society but they do not have the ability to go into court.”

This article was published on 7 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

07 Apr 14 | News and features, Venezuela, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Image: Sergio Alvarez/Demotix)

Like other countries, Venezuela’s young are eager to explore the world. Every opportunity to learn becomes important in the formation of the young mind. In Venezuela, a crippled education system prevents normal development. While the well-born go to private schools and have access to every benefit, the mass of Venezuela’s students confront an educational system that tells them: “You can’t but you tried.”

The most embarrassing and painful thing about the deplorable state of the country’s schools is the level of the government’s indifference. Though the government of Nicolás Maduro offers programmes like “Simoncito”, “Mision Ribas” and “Mision Robinson” these is basic education that doesn’t adequately prepare students to pursue higher studies. The programmes seem to condemn the disadvantaged among Venezuela’s population to a remedial existence. If some of these children make it to higher education, the odds are stacked against them and their families.

In the end, it all comes down to money. Venezuela needs to spend more to let students be students. But with foreign reserves short, all but national priorities are left off the funding list. Every area of science instruction needs improvement. Budgets are not even close to covering the costs of labs, let alone providing learning aids or even actual textbooks. A prize-winning robotics team at Caracas’ Universidad Simon Bolivar works with outdated electronics that are often patched together. When the team wanted to take part in an international competition, they were denied assistance — meaning just a few of the team could do it because that was all they could afford to pay out of their own pockets. Another group, which took part in the Latin American conference of the model UN, found themselves staying in primitive conditions in Mexico because they were denied dollars, the currency they needed to pay bills. Despite the discomfort, the group won six awards.

Even with the obvious deficiencies in education, Venezuela has a large population of well-prepared professionals across a wide spectrum of expertise. But based on political affiliations, these people cannot work for the development of the nation. No wonder Venezuelans have begun to leave the country in search of a better future for themselves and their families. This exodus is manifesting itself worst of all among teachers. The ramshackle education system can ill afford this brain drain. But, again, it’s understandable when even those with advanced degrees from internationally respected institutions earn less than approximately £40 per month. When the government’s own basic food basket is priced at nearly £200 per month, it’s impossible to support a family without second or third jobs. Under strict rules, teachers are not allowed to apply for the loans that could support home or car ownership. In effect, teachers are sentenced to live with relatives for life. Yet they continue to teach out of love for the craft with the hope they they can raise a new generation of Venezuelans who can think for themselves and question dogma. Without them, the youth of Venezuela would be lost.

In recent interviews, the educational minister Hector Rodriguez said: “We are not going to take you out of poverty for you to go and become opposites.” His statement meant that Venezuela’s students should understand that their wings are already clipped and any dream of progress or improvement is invalid.

The government’s approach to education aims to make Venezuelans think it has the absolute truth and will decide what’s right for students. The lower classes won’t have any choice but to believe what they are told.

After 15 years Venezuelans have become accustomed to waiting for the government to wave a magic wand to provide what they need. The sense of personal responsibility now seems lost. Effort doesn’t deliver results, so Venezuelans don’t try. It’s an indirect way for the government to choose a person’s destiny.

At the same time, scarcity – and not just in an educational sense – is the new normal. Everyday basics like toilet paper, coffee or cooking oil are the subjects of long hunts that lead to the back of an equally long queue. Hospitals cancel operations for lack of supplies and cancer patients miss treatment for lack of medicine. And even though the government’s late March devaluation of the bolivar will fill the shelves in the shops, the average Venezuelan will be unable to afford the supplies.

For the government, scarcity is just a glitch — just like the blackouts when “iguanas eat the cables” – and not because the energy minister is not doing his job.

It’s impossible to walk down streets without being paranoid — one eye on the road and the other keeping watch of everything around you. On average 48 people are murdered in the country every day. Venezuelans can be beaten and robbed with no recourse to justice because the police and the criminals are often in partnership.

The Bolivarian Revolution was supposed to bring improvements, but the lack of daily essentials and a robust education system leads one to the conclusion: The basement has a bottom.

This article was posted on April 7, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

04 Apr 14 | Europe and Central Asia, Events, United Kingdom

Thousands of protesters took to the streets of Istanbul on 1 June in the capital’s Taksim Square during demonstrations over plans to turn Gezi Park into a shopping mall. (Photo: Akin Aydinli / Demotix)

Protests are commonplace in many democracies all over the world, but in the last year there have been several limitations and blockades made to this right. From the protests on several university campuses, to those in Istanbul’s Gezi Park, to the more recent protests in the Ukraine, the world has seen that the right to assembly can still be seen as a direct threat to the authorities and one they wish to suppress. However, are there ever instances when protests should be suppressed, whether because they put the population at risk or are representing an extremist ideology at odds with the rest of society?

Index on Censorship and Sussex University Politics Society are hosting a panel debate to look at the importance of the right to assembly to freedom of expression at Sussex and around the world.

The panel will be a diverse range of free speech experts, and media, academic and student representatives.

Join us on Tuesday 8th April at 6pm in Fulton 104 on Sussex University campus to debate and discuss these important issues.

04 Apr 14 | News and features, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

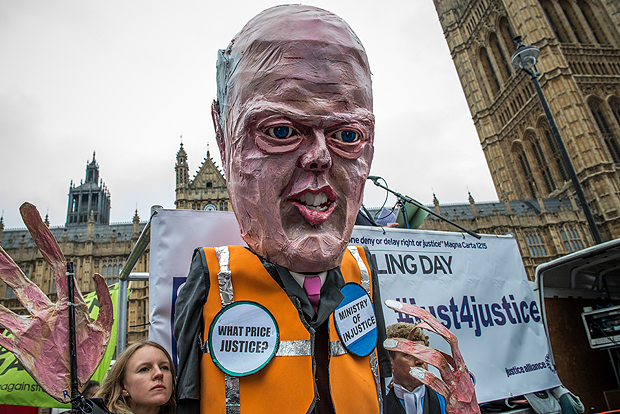

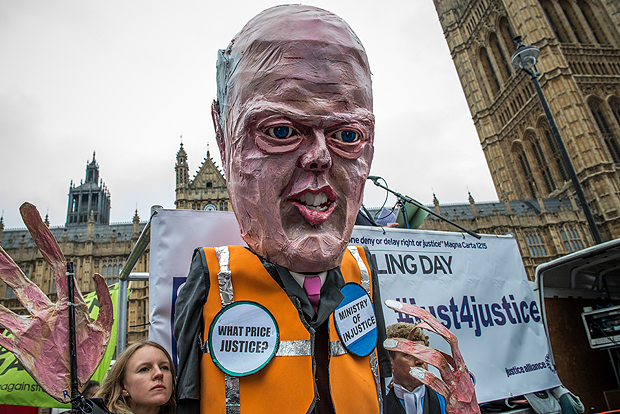

Activists marched with an effigy of justice minister Chris Grayling in March to protest legal aid cuts. (Photo: Velar Grant / Demotix)

The British government is making it easier for those in power to break the law – and it’s using a fantasy about left-wing pressure groups to justify it.

Judicial review is becoming a real pain for those who run Britain. However much they like to think they’re above the law, they frequently get reminded that they’re breaking it. Last October, for example, health secretary Jeremy Hunt’s attempt to implement cuts at Lewisham hospital was stymied by a judicial review funded by campaigning organisation 38 Degrees.

By then David Cameron had already announced his determination to clamp down on “time-wasting” judicial reviews. What’s motivating this move is the sheer number of cases now being brought. There were around 15,700 judicial review cases in 2013, up from around 4,300 cases in 2010. Judicial review – the way in which the legality of the state’s actions can be tested by judges – is not clogging up the courts, though. Just a fifth of those put forward were granted permission to succeed in 2012.

The executive’s correct response should be to do more within the law, not outside it. Instead justice secretary Chris Grayling is leading a push to impose a chilling effect on judicial review that opponents say would make the process punitively expensive – effectively making it that much easier for the executive to get away with it.

“Britain cannot afford to allow a culture of left-wing-dominated, single-issue activism to hold back our country from investing in infrastructure and new sources of energy and from bringing down the cost of our welfare state,” he wrote in an article for the Daily Mail.

“We need to make decisions quicker and respond to issues more quickly in what is a true global race… the left does not understand this.”

Senior members of the judiciary don’t understand it either. “We note that the consultation paper does not contain any evidence of inappropriate use of judicial review as a campaigning tool, and it is not the experience of the senior judiciary that this is a common problem,” they observe drily.

Their bafflement has not stopped Grayling from manoeuvring inside the corridors of parliament. He’s been attempting to win over MPs by talking up these changes as a power grab by parliament, not the government. Yet because it’s ministers who control what goes on in the Commons, Grayling is effectively seeking more power for himself and his colleagues, not backbench MPs. If nothing gives in the parliamentary process, he’s going to succeed.

What’s now working through the Commons in the criminal justice and courts bill is a cocktail of measures which together will cut back on ordinary people’s access to justice.

Top of the list is a move which requires judges to dismiss any judicial review claims where an abuse of the process wouldn’t have made a difference to the end result. Take a new zebra crossing application, for example. If 40 homes are affected and only 39 are notified beforehand, a judicial review could be brought by the 40th person complaining of the result. But if all 39 had already backed the crossing, should the court’s time really be taken up?

Absolutely, civil liberties group Liberty argues. “Even where individuals are not satisfied with the outcome of a decision-making process, the fact that they have been given a fair hearing often serves to satisfy their sense of justice and promotes trust in state institutions and democratic processes,” its submission to the MoJ states.

Under the government’s proposals, the concept of a fair hearing is being abandoned completely.

Even those cases which do still qualify may find they miss out because, under the government’s original proposals, the timeframe for bringing a claim is being halved from three months to six weeks.

But it’s worse than that. In addition to making it harder for judicial reviews to get into court by changing the rules, the government is trying to put many third-party groups getting involved altogether.

In many cases it’s charities like Liberty which get involved – relatively small organisations that could never afford to pay full legal costs if they lose. Yet that is exactly what the government is going to make them do.

The Ministry of Justice’s (MoJ) own impact assessment has already worked out the implications of this change. “Interveners may be less inclined to intervene voluntarily if they were more exposed to the costs their actions place on claimants and defendants,” the document states. That’s putting it mildly.

What about the Liberal Democrats, who in opposition styled themselves as the defenders of personal freedoms? They have left the wrangling with ministers to MP Julian Huppert, who is ignoring most of the measures in favour of the interveners clause. His goal is to achieve a meaningful concession – and believes he may be getting somewhere.

“I was very pleased the government has agreed to look at alternative wording on interveners,” he says.

“The wording as it currently stands is completely unacceptable to me because it would stop very good meritorious interventions from happening because of the chilling effect.”

Huppert has been the victim of some cruel jibes from Labour’s shadow justice minister Andy Slaughter, who has predicted “some nugatory or insubstantial concession will be made in the future”. It remains to be seen who will be proved right. If nothing changes, many third-party ‘interveners’ will decide it’s simply not worth the risk.

Eventually the bill will arrive in the Lords, when peers are expected to tear into the proposals. Lord Pannick, who has proved one of the spikiest thorns in this government’s side over the years, is among those who have already spoken out against the ‘unconstitutional’ nature of the changes.

Perhaps ministers will be more prepared to make concessions in the second chamber. They certainly weren’t interested in responding to the responses to their consultation on judicial review, which were weighted about 10:1 against the government’s proposals.

“We want there to be a rebalance of what has, in my view, become a risk-free enterprise for many organisations and for which the taxpayer is shouldering the burden,” justice minister Shailesh Vara explained during the committee stage debates.

“We are seeking to set a sensible position on precisely when the taxpayer is expected to foot the bill for others’ decisions. This is not purely a question of quantum but also one of the good stewardship of public finances.”

Grayling is having a tough run-up to Easter. He’s been criticised over the prisoner books ban. He’s been condemned for presiding over sweeping reductions in legal aid. Now he is going further still with judicial review. As Vara’s comments reveal, Grayling is literally cutting justice once again.

Valerie Vaz, the Labour backbencher, has this to say: “It isn’t clear what apparent mischief the government are trying to prevent, other than to interfere with the workings of the court.

“We ought to remember the dictum, ‘be ye ever so high, the law is above thee’, but the government appear to be saying, ‘be ye ever so high, the government are above thee’.”

This article was posted on April 4, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org