21 May 2007 | Uncategorized

For four months at the end of 2005, I was given access to an extraordinary series of Foreign Office documents concerning the government’s strategy to tackle the threat of radical Islam at home and abroad. Literally dozens of emails, position papers and policy discussions came my way. It became clear that someone within Whitehall was deeply disturbed about the direction of British foreign policy, especially the strategy of engagement with groups and individuals on the Islamist extreme right. At one point I was receiving so many documents that I barely had time to read their contents, let alone judge whether there was a story in them.

But stories there were. The documents showed that senior figures in the Foreign Office believed that Britain’s policy in Iraq had led to an increase in radicalism among young Muslims, something the prime minister was denying at the time. I published the story in the Observer, where I was working as home affairs editor. But that was just the beginning.

The leaks provided me with a further news story for the Observer about plans to infiltrate extremist groups, and with features for the New Statesman on CIA rendition flights, diplomatic engagement with Egypt’s banned opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the panic that had engulfed the Foreign Office as a result of the disclosures. The documents also formed the basis of a Channel 4 documentary on the government’s troubled relationship with radical Islam and an accompanying pamphlet, When Progressives Treat with Reactionaries, for the think tank Policy Exchange. The leaks were a journalistic goldmine. The revelations about the compact between the Foreign Office and radical Islam also went some way towards changing government policy towards the self-appointed representatives of Britain’s Muslim community, such as the Muslim Council of Britain.

It is difficult to imagine a series of documents that could have been more in the public interest to disclose. Decisions being made in the Foreign Office, with a direct effect on the British people, were taking place with little or no consultation. In particular, the Foreign Office had embarked on a detailed strategy of engagement with Islamists at home and abroad without reference to Parliament or even, it seemed, the prime minister himself.

owever, at the end of January 2006 my source was arrested under suspicion of breaching the Official Secrets Act. I have not heard from him since. The latest news is that he has been bailed until June, while investigations continue. By then, his life will have been held in suspension for 18 months: this at a time when Labour politicians complain that the ‘loans for peerages’ investigation has dragged on for a mere 12 months with no charges being brought.

If, and when, the case comes to trial it will provide a fascinating test of the secrecy laws. The documents, many of which have been collected in the Policy

Exchange pamphlet, are also available online. They provide a unique insight into government thinking on Islam between 2001 and 2006, a period that encompasses the suicide attacks on New York and the bombing of London. Reading through them again, it is difficult to imagine how national security can have been seriously compromised by the disclosures, which contributed considerably to the national debate on one of the most important issues of our time. Communities Secretary Ruth Kelly is known to have been influenced by the disclosures in making her decision to seek new grassroots Muslim partners in the battle for hearts and minds. The Policy Exchange pamphlet has also helped inform the Conservative policy group on national and international security headed by Pauline Neville-Jones, a former chair of the Joint Intelligence Committee who also served as political director in the Foreign Office. It would be a delicious spectacle to see Kelly and Neville-Jones called as witnesses for the defence in any

trial that results from the Foreign Office leaks.

However, it is not difficult to see what motivated the arrest. The leaks were proving intensely embarrassing and coincided with a crackdown across Whitehall against unauthorised disclosures. This had been sparked by a separate leak of a memo said to outline plans by President George W Bush to bomb the Arabic television station Al Jazeera in April 2004. Following the publication of the claims in the Mirror, Cabinet Office civil servant David Keogh and parliamentary researcher Leo O’Connor were charged under the Official Secrets Act.

In opposition, the Labour Party had fought the introduction of the 1989 Official Secrets Act, arguing that a ‘public interest’ defence should be inserted

into the legislation to give protection to genuine whistleblowers. During the parliamentary debate, Shadow Home Affairs spokesman Roy Hattersley said that the definition of harm to national security ‘is so wide and so weak that it is difficult to imagine any revelation which is followed by a prosecution not

resulting in a conviction’. Frank Dobson, who went on to serve in Tony Blair’s first cabinet, added: ‘Surely we as a Parliament have not sunk so low

that we want to introduce new laws to protect official wrongdoing.’

Once in power, the Labour Party had no such qualms. The Blair government has wielded the big stick of the Official Secrets Act with alarming regularity since it came to power. In August 1997, just months after winning an election on a promise of new openness and transparency in government, the new government faced a serious predicament in the person of David Shayler, an MI5 officer whose revelations about the intelligence service were published in the Mail on Sunday.

These included details of files kept on senior Labour politicians such as Jack Straw, Peter Mandelson and Harriet Harman. More seriously, Shayler later claimed that officers from Britain’s foreign intelligence service, MI6, had participated in a plot to assassinate Colonel Qaddafi of Libya.

Despite the fact that Shayler’s claims referred to a period before Labour came to power, the new government pursued him relentlessly, requesting his

extradition from France, where he had set up home after leaving the security service. This pursuit extended to journalists who wrote about Shayler, and in

2000 I found myself in court after publishing an article in the Observer about the Libya plot, in which I said the newspaper had been given the names of the spies allegedly involved in the plot, but had been prevented from publishing them for legal reasons. (The officers’ names, David Watson and Richard Bartlett, have since entered the public domain, but they have never been prosecuted for their

alleged crimes.)

The Observer successfully fought an order to hand over all documents relating to my dealings with David Shayler and established an important precedent in media law that has made it more difficult to seize journalistic material. But it did not help David Shayler, who returned to Britain in 2000 to face trial. He was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment in November 2002 for breaching the

Official Secrets Act, after more than five years of fighting for his claims to be investigated by the government.

David Shayler did not succeed in his own case, but his lawyers did establish an important precedent for future whistleblowers. In 2002, the House of Lords had decided that Shayler’s lawyers could not use a public interest defence. It also decided that the 1989 OSA was compatible with human rights legislation.

However, it did establish that in certain cases a ‘defence of necessity’ could be used if a whistleblower had acted because there was an imminent threat

to human life.

Less than six months later an opportunity arose to test the legislation. In March

2003 as the military preparations for war in Iraq gathered pace, a young woman in her late 20s walked into her boss’s office at GCHQ, the government’s secret eavesdropping centre in Cheltenham, and admitted to leaking a document of the highest possible classification of secrecy. Katharine Gun, a junior Mandarin Chinese translator, knew her career was at an end and that she could face a long prison sentence. But she believed the contents of an email she had received in the course of her work could stop the war. She believed her action could save lives.

The email, dated 31 January 2003, was from Frank Koza, head of regional targets at the National Security Agency in the United States, and asked for British help in spying on the United Nations, which was immersed in an intense debate about whether to authorise an attack on Iraq. Britain was arguing for a second UN resolution to specifically sanction the invasion, without which many thought the war would be illegal.

Key to any vote were the so called ‘swing’ nations, Chile, Pakistan, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Guinea and Angola, temporary members of the Security Council,

whose votes were essential in gaining legal cover for the war. Koza was demanding a ‘surge’ in spying activities to give the US an ‘edge’ in the negotiations.

He was desperate to know the voting intentions of the ‘swing six’, but also hinted that private information about individual diplomats should be amassed in case blackmail was necessary.

I ran the story about the leaked email in the Observer on 4 March 2003, three weeks before the outbreak of war. It had taken nearly a month from leaking the document to its appearance in the press and Gun was in a state of almost unbearable tension. She immediately owned up to being the source of the leak and was arrested by the police for a suspected breach of the Official Secrets Act. Gun believed that when the UN discovered what was going on, they

would never allow the war to go ahead. What she didn’t realise at the time Katharine Gun after charges against her were dropped, London February 2004

was that George W Bush had already decided on regime change in Baghdad, with or without the United Nations.

However, when the case finally came to trial in February 2004, the prosecution failed to present any evidence and the case was dropped before it had begun. At the time, speculation suggested that the government had decided to drop the case because it would have led to the publication of the attorney general’s legal advice on the legality of the war, which was initially equivocal. But the Crown Prosecution Service always said that the reason was far more banal: that it had become clear that it would be impossible to fight Gun’s defence that she had acted

to save lives.

Although it is impossible to know precisely why the government dropped the Gun case, it is probably fair to say that the ‘defence of necessity’, established by David Shayler, helped save Katharine Gun from prison. It is perhaps no surprise, then, that the government has indicated its intention to close down the defence in future cases. Last July, The Times reported the intention of the new Home Secretary, John Reid, to remove the necessity defence and suggested that he would present the necessary legislation in last autumn’s Queen’s Speech. This did not materialise, due to a lack of parliamentary time. But the Home Office has confirmed that it is keeping the OSA under review and will revisit the defence of

necessity as soon as it can.

Campaigners still believe an amendment to the 1989 Act is imminent. Julie-Ann Davies, who was arrested in connection with the Shayler case in 2000, has

spent the past seven years researching Britain’s secrecy laws and is currently studying for a PhD at Glasgow University. She said: ‘I have no doubt the government intends to act. Whenever a window of public interest opens up, they close it.’ Former senior BBC journalist Nick Jones is now chair of Reform the Official Secrets Act (Rosa), which campaigns for a public interest defence for whistleblowers in national security cases. He said the Al Jazeera trial marked an intensification in the drive for government secrecy: ‘There does seem to be a new push, triggered by the war on terror, to restrain journalists who want to write in this area. Meanwhile, all talk of protecting whistleblowers has disappeared in a puff of

smoke.’

The paradox is that in the present circumstances the more serious the disclosure, the more chance of running a successful defence. My source, for example, who could only be accused of leaking ‘confidential’ rather than ‘secret’ documents, would not have recourse to the necessity defence. He would have to fall back on a defence that said he had acted in the public interest, something of which Labour seems to have lost sight after ten long years in government.

Martin Bright is political editor of the New Statesman

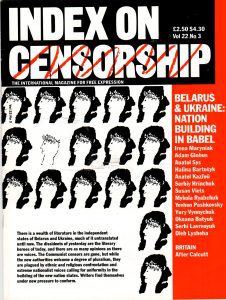

Subscribe to Index on Censorship here

15 Jun 1975 | Magazine Editions, Volume 4.02 Summer 1975

Late last year Index on Censorship circulated to six hundred artists and intellectuals around the world a questionnaire about the cultural boycott of South Africa. The survey was announced in our first issue of 1975. At that time a few early replies were published, together with a brief history of the cultural boycott, and readers were invited to contribute their own opinions on the subject. The present article gives a general overview of the results of the survey among artists, followed by extracts from the more than sixty replies which we have received to date. (March 1975.)

Responses have come from (among other places) India, Argentina, Portugal, Turkey, Eastern Europe and the African continent, as well as from Britain, the United States and South Africa itself, the countries where the boycott debate has focussed in the past. We have heard from playwrights, poets, novelists, publishers, journalists, theatre directors, film critics and technicians, performing artists and academicians. Although the original mailing-list was not a scientifically-chosen sample, these replies can at least be considered representative of the main professional and artistic groups which have been involved with the cultural boycott since its beginning in 1957. While some of the respondents had previously signed petitions or otherwise signaled support or disapproval for the boycott, few had ever before expressed themselves fully about the question. This, together with the depth and individuality of the replies, lends considerable interest and importance to the results of the survey.

In an early reply to the INDEX questionnaire, the black South African poet Dennis Brutus gratefully acknowledges ‘your efforts to discuss and evaluate a problem which bristles with complexities though the essential human issue is certainly clear’. We are in turn grateful to Mr Brutus and to the other respondents for so readily understanding our purpose and for taking up so enthusiastically the discussion which INDEX sought to open. We hope that our readers will continue to be drawn into the debate, as they were by our first article on this subject, and that they will continue to send us their own arguments for and against the cultural boycott. Selections of these will be published in later issues.

The following summary of artists’ views has been organised for the sake of convenience around the six questions which make up the boycott questionnaire. It will be obvious from the extracts, however, that many responses cannot be categorised even in the most general terms of support or non-support for the arts boycott. Therefore the statistical estimates which appear in the summary must be accepted as being only rough ones. We would remind readers that our primary purpose has been to open a debate about a complex problem, not to take a poll. We would also point out that an important group of artists to whom the questionnaire was sent-that is, black South Africans living in their native land – are not represented at all among the respondents. We believe this has happened because official South African policy, which equates support for sanctions against South Africa with support for violent overthrow of the government, makes boycott a subject too dangerous for black artists within the country to discuss. At any rate the fact that this group is missing should be kept in mind when weighing the results of the survey. Finally, a special group of twenty-seven anonymous student-writers from the United States are present among our respondents. Their opinions were solicited as part of an experiment, using the INDEX questionnaire, which was conducted by Dennis Brutus at the University of Texas. Since for these students the cultural boycott is a theoretical rather than an actual problem, as it would be for practising artists, we have recorded their views separately.

1. Do you support a cultural boycott of South Africa while apartheid continues? If so, why? If not, why not?

Of fifty-nine artists and intellectuals responding to the survey, twenty-three express themselves firmly in favour of the arts boycott. Nineteen express themselves firmly against it. Fourteen take positions about the boycott which fall between absolute yes or no. Three respondents take no stand at all.

The sampling of student opinion produced a result heavily in favour of the arts boycott. Out of a total of twenty-seven responses, there were twenty-five positive replies and two negative ones. The arguments on both sides are clear-cut. None of the students’ replies takes account of the complexities which troubled so many of the older respondents to the boycott questionnaire.

A number of reasons for supporting the arts boycott can be identified in the overall sampling. The British actor David Markham feels it is imperative to support the cultural boycott, ‘because any other attitude implies agreement with apartheid’. Muriel Spark, the English novelist, and Luzia Martins, director of the Companhia Teatro Estudio of Portugal, both point to the fundamental illegality of apartheid laws as a justification for boycott action. Sophia Wadia, editor of Indian PEN, the writers’ journal, in Bombay, makes a related argument for the cultural boycott: ‘A cultural boycott is justified on the ground that artists should refuse to be turned into the retainers of an unjust power group.’ Andrew Salkey, the West Indian poet, supports the boycott because it causes ‘minimum deprivation’ to the black majority and maximum deprivation to the oppressive minority.

An argument that appeals to many supporters of the boycott is that the black majority itself in South Africa has called for the international arts boycott to continue, through representatives like Chief Albert Luthuli, the African National Congress and other black organisations. One anonymous respondent writes, ‘The ANC are more effective as leaders of the struggle in South Africa than Arnold Wesker, and they have asked for it [the boycott] as the weapon they want against apartheid.’ The same general idea is echoed by British authors Brigid Brophy, Henry Livings and Alan Plater, by Alan Sapper of the British film and television union ACTT and by Barry Feinberg, a South African writer now living in exile. South African novelist Nadine Gordimer also supports a cultural boycott, as ‘guided by those living in South Africa who are vigorously opposed to apartheid and understand best its cultural consequences.’ Another group of respondents argues for the boycott less on grounds of principle than as a successful tactic for inducing change in South Africa. In using this argument, Dennis Brutus and the Bishop of Stepney, Rev. Trevor Huddleston (two of the original organisers of the arts and sport boycotts of South Africa) agree with two of our Eastern European respondents, the Polish novelist Wlodzimicrz Odojewski and the theoretician Stefan Morawski. Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian poet, also has a pragmatic reason for supporting the boycott: ‘At the very least it contributes to the psychological siege of apartheid and this in itself cannot be negative or futile.’ Two other African writers, Kole Otomoso of Nigeria and Syl Cheney-Coker of Sierra Leone, defend the arts boycott on the basis of their philosophical attitude toward art itself.

Otomoso states, ‘Art is a verbalisation of the dignity of man. Where that dignity is denied, what is there to verbalise except falsehood?’

Some contrasting arguments against the cultural boycott can be mentioned. An important philosophical reason and a pragmatic one are supplied by André Brink, the South African novelist whose latest work Looking on Darkness is the first piece of Afrikaans literature ever to have been banned in South Africa. He opposes the boycott because, first,’vital cultural products can help to stimulate change in South Africa’ and because, secondly, ‘a total boycott (which might be effective) is impracticable, especially in view of South African laws permitting copyright infringement’. The notorious South African copyright laws (see INDEX 1/75, p.37) are also mentioned by another Afrikaans writer, Casper Schmidt, in his argument against the arts boycott. More commonly, however, opponents of the arts boycott argue that it misses its intended target, for only the committed opponents or the innocent victims of apartheid are hurt by cultural isolation, while the bigots remain unchallenged in their prejudices. Several commentators point to an analogy between the artists’ boycott of South Africa and South Africans’ censoring of artists. For example, the South African writer Mary Benson states, “The SA Government censors and bans, why should we who are striving for a just society in that benighted country add to the intellectual and spiritual restrictions?’ John Pauker, an American poet who has travelled to South Africa for the us Information Service, argues, ‘I go wherever they let poetry in.’

A substantial number of respondents to the INDEX questionnaire refuse to classify themselves as either supporters or opponents of the cultural boycott. The reasons vary so widely – from a desire to take ‘each case on its merits, or demerits (Dan Jacobson, South Africa) to a desire to carry out a strictly personal form of boycott (Kurt Vonnegut, USA) – that these replies are best left to be read in full.

2. Do you think that cultural boycott should be used as a form of protest against other governments? Which governments, for example?

Replies to this question follow a pattern close to that of Question 1. Generally those who are willing to support a cultural boycott against South Africa are also willing to consider similar protests against other governments which seem to the respondents to have abridged human rights. Those who are opposed to the South African boycott are also opposed to the use of cultural boycott against other countries. One exception is Henry Livings, a British writer who signed the original 1963 playwrights’ ban. He feels that ‘no other tyrannical government would be vulnerable in the way the SA government is; they seek acceptance as civilised people, it should be denied them’. British playwright Alan Plater makes a second point about the uniqueness of South Africa as a target vulnerable to protest specifically by British artists: ‘South Africa .. . is an English-speaking country and it follows that the work of English writers is in demand. . . .’ Another exception to the pattern of replies is that of Stefan Morawski, the Polish writer and theoretician. He agrees with the principle of cultural boycott, and to Question 2 he answers that cultural boycott would ideally be useful against any government which curtails civil liberties. But he adds that, in practical political terms, such an expanded use of cultural boycott would be futile because it would involve ‘intervention. . . into the internal affairs and ideological battles’ of particular countries. Morawski goes on to note that this last statement refers to the Soviet Union: ‘That’s why I am against mixing up the question of Soviet Jews with the South African problem. The first one has nothing to do with racism: it is a political issue which needs a peremptory response but of another kind.’

Because the Soviet Union recently has become the target of something approaching cultural boycott over Jewish emigration and other problems of civil liberties, it is interesting to examine together the replies of all the Soviet and Eastern European respondents on this point. By and large they remain consistent with their position on South Africa. The Polish novelist Wlodzimierz Odojewski, for example, supports the cultural ‘boycott of any country which practises racial, nationalistic or religious persecutions’. He names the Soviet Union directly as one instance of a country which persecutes special national and religious groups and thus should come under boycott. On the other hand, Zhores Medvedev (the Soviet scientist and dissident writer), Ludĕk Pachman (the Czech chess-master) and A.J. Liehm (the Czech film critic) all oppose the cultural boycott of South Africa. They also oppose arts boycotts against the Soviet Union or Eastern Europe.

Those who support cultural boycott as a form of protest open to artists give many examples of countries besides South Africa and the Soviet Union where such protests might be appropriate. Chile, Brazil, Spain, Uganda, Israel, Great Britain and Rhodesia are all mentioned as possible targets. For example Kole Otomoso, the Nigerian writer and editor of the journal Afriscope states that both Uganda and Rhodesia should come under an arts boycott because of their repressive policies.

3. Do you think that a cultural boycott could be extended beyond the theatre and performing media to other aspects of cultural life (for example films, sport, books)?

Two respondents (Zhores Medvedev and Wlodzimierz Odojewski) understand the question as applying mainly to artistic productions being boycotted abroad. Medvedev opposes any such boycott, arguing from the example of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s novel: ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was published partly as a result of a decision by the Politburo, but it would be nonsense to ignore such a book because it was approved by the leaders of the Communist Party.’ Odojewski feels that anti-apartheid productions by South Africans should be positively encouraged.

A majority of those who discuss the question (15 out of 36 respondents) draw attention to sport as an area where the tactic of boycott has been unequivocally successful. Some like Frank Bradlow, the chairman of the South African PEN Club (Cape Town), separate sport from cultural life generally; some do not. Some respondents who disapprove of other forms of cultural protest by playwrights or performers, nevertheless support the sports boycott wholeheartedly. Sir Robert Birley, the British educationalist, and Mary Benson are two examples. In contrast, Jillian Becker, another South African novelist, believes that South African sportsmen would benefit much more by encountering foreigners and hearing direct criticism of apartheid.

In other replies the boycott of public or university lecturing by academicians or authors is mentioned. It is opposed by Nadine Gordimer, Robert Birley and Professor L. C. Knights. But British novelist Margaret Drabble favours such a boycott. The stoppage of books for the South African market is opposed by Margaret Drabble, the playwright John Bowen and British publisher Rex Collings. Kole Otomoso and British novelist Bernice Rubens, however, would press for a book boycott Several respondents, Wole Soyinka, John Bowen, Nadine Gordimer, Bernice Rubens among others, urge the extension of the cultural boycott to films. Margaret Drabble and the critic Martin Esslin disagree. Another extension of the boycott — to television – is urged by playwright Alan Plater: ‘What is crucial is that we must have our defences and our weapons in good order ready for the coming of television in South Africa. Our programmes will be in demand. My hope is that the Writers Guild of Great Britain will insist on a barring clause in writers’ contracts.’South African Frank Bradlow urges the opposite. He argues that extending the cultural boycott ‘is even more counter-productive, especially with television which is a subtle influence on racial attitudes’. Finally, Ethiopian writer Sahle Sellassie expresses himself in favour of boycotting music, dancing and other forms of ‘pure entertainment’ for South Africa, as distinct from literature or theatre of ideas.

4. Do you think that artistic and sporting events from South Africa which tour abroad should come under boycott?

Generally the responses to this question, as to Question 3, treat sport as a separate case where the boycott of touring groups can be especially effective and should be continued. But most respondents would not boycott events which imply a criticism of the status quo. In this connection repeated mention is made of the recent theatre tour to England and the United States by Athol Fugard and a company of black actors from the township of Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Martin Esslin notes, for example, ‘Common sense rather than rigid rules should apply: otherwise plays like Athol Fugard’s would not have been seen in this country.’ Daniel Mdlule, a black South African living in exile, states that the ‘false ambassadors’ from South Africa, those who are apologists for apartheid, should definitely be boycotted. But he would not boycott others – white South Africans like Nadine Gordimer who speak out clearly against racialism and particularly black South African artists like Welcome Msomi, the Zulu dramatist. Mdlule points out quite movingly that black artists are frequently caught in the situation where their access to public notice is severely restricted within South Africa, until they have been successfully noticed abroad.

5. Do you think that there should be specific areas exempted from a cultural boycott? Which, for example?

The word ‘areas’ in this question is open to be understood in either a geographical or a cultural sense. More frequently, respondents took the second choice, although Muriel Spark does propose to exempt from cultural boycott ‘underdeveloped countries where the rich and literate could derive cultural and educational benefit, and where poverty takes care of the access to culture anyway’. David Markham would exempt ‘all countries where internal freedom of thought and action is allowed’ (he suggests Finland tentatively under this heading).

Among those who speak up for the exemption of certain areas of cultural life from the arts boycott, most (including Margaret Drabble, Martin Esslin, Wole Soyinka and British writers Christopher Hope and Naomi Mitchison) mention books. Union leader Alan Sapper states that only factual news reporting is allowed through the boycott which is operated by British film and television technicians. Henry Livings would exempt radio. Several respondents are firm on the point that there should be no exceptions. Bernice Rubens, for example, states, ‘A boycott must be total.’ She acknowledges, however, that’ there are situations which tempt our co-operation’.

6. If you are opposed to the principle of apartheid and also to the idea of a cultural boycott, what other kinds of sanctions or gestures would you propose, if any?

Thirteen respondents, some of them supporters of the cultural boycott, offer additional suggestions in reply to this question. The proposals mostly range themselves around three kinds of sanctions: stricter economic boycott, wider dissemination to South Africa of specifically anti-apartheid ideas and greater cooperation with the protests of artists within South Africa. Economic boycott instead of cultural boycott is urged by Zhores Medvedev and by Yaşar Kemal, the Turkish novelist. Others, like Syl Cheney-Coker of Sierra Leone and Yousuf Duhul of Somalia urge the use of economic boycott as well as cultural boycott. The South African playwright Ronald Harwood prefers as an alternative to cultural boycott what he calls ‘cultural bombardment’ of South Africa in order to destroy her prejudices. The same general idea of opening wider cultural contacts with South Africa is repeated by Frank Bradlow of South African PEN and Lionel Abrahams, the Johannesburg publisher. André Brink, on the other hand, stresses the importance of world support for artists struggling against apartheid within South Africa. In urging a similar point, Christopher Hope and Lionel Abrahams both mention an important protest against apartheid by artists which was staged recently in South Africa and which was successful. Details of the action, as described by Lionel Abrahams, are worth quoting here ‘Against the background of a sudden proliferation of Black poets writing in English where none had been notable before, the State’s annual Roy Campbell poetry competition was declared to be open to Whites only. Vociferous protests were ignored. Finally some eighty White poets signed a pledge to boycott the competition unless it were made open to all. The effect of such a boycott would have meant that the competition, if operable at all, would lose whatever prestige it had – which, no doubt, is why the presentation of the pledge was followed almost immediately by an announcement that the Whites-only ruling had been made in error.’

In closing this summary of the INDEX survey, we would point out the universal bias against apartheid which is expressed or implied in every response we have received. Whether or not they support the cultural boycott, these artists oppose racial discrimination, and to a person they base their replies on a fundamental sympathy for the sufferings of Black people in South Africa.

This summary has been compiled for INDEX on Censorship by Dorothy Connell.