7 Jun 2012 | Middle East and North Africa, Tunisia

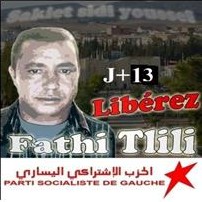

13 days after police arrested him, Fathi Tlili, a coordinator for the Leftist Socialist Party (Le Parti socialiste de gauche in French), is still behind bars.

The arrest followed Tlili’s participation in protests which swept Sakiet Sidi Youssef, a small and underprivileged town in the northwest of Tunisia. On 25 May, the town’s inhabitants organised a general strike demanding employment and a local development boost.

The strike, which paralysed the town’s little economic activity, ended in acts of vandalism when unemployed protesters set official buildings and state-owned cars on fire.

Police are accusing Tlili of “inciting riot”, and of “breaking down” the local delegation’s rear door building. The PSG has denied these charges, claiming that Tlili and other party activists tried to stand up to acts of vandalism.

In a communiqué released on 3 June, PSG Secretary General Mohamed Kilani described the legal proceedings against Tlili as “a political trial”. He claims Tlili was badly treated while in prison.

“After visiting him in prison, Fathi’s wife asserted that her husband was physically abused, and badly treated. She noticed the bruises on his body,” the communiqué stated.

The Tunisian extreme left is often blamed for fuelling protests and social unrest. I an interview given to Al-Jazeera last January, Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki accused the “extreme left” of “manipulating, and politicising social protests in order to stir up trouble”.

7 Jun 2012 | Index Index, minipost, United Kingdom

The Spectator has been ordered to pay £5,600 after admitting a November 2011 article about the trial of Stephen Lawrence‘s killers breached a court order. Associate editor Rod Liddle’s piece claimed defendants Gary Dobson and David Norris — who were convicted in January 2012 of Lawrence’s 1993 murder — would not get a fair trial. It appeared in the magazine after the trial had started and an order imposed on reports that could influence the jury’s view of the defendants. The judge said the article caused a brief moment in which the trial was in jeopardy, but the magazine’s swift apology and removal of the piece online meant it was not undermined. The magazine’s lawyer apologised for its “bitterly regrettable” failure to make checks.

7 Jun 2012 | Europe and Central Asia, Index Index, minipost

Former Belarusian presidential candidate Andrei Sannikov was removed from a train travelling from Minsk to Vilnius at a station near the Lithuanian border yesterday. The activist, who was released from detention and pardoned by Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko in April, was reportedly heading to a conference in the Lithuanian capital. On 2 June fellow activist Dmitri Bandarenka was also removed from a train travelling from Vilnius to Minsk. His personal belongings were searched and he was made to strip down to socks. Bandarenka was travelling from Lithuania, where he had received medical treatment, and arrived in Minsk on the next train.

7 Jun 2012 | Uncategorized

Rod Liddle was stupid to write his article on the trial of Gary Dobson and David Norris, and the Spectator was stupid to publish it. Now the magazine has been fined — not for contempt of court, though anyone with a faint awareness of media law knows that law was broken, but for the even more straightforward offence of breaching a court order. A judge said don’t do it and they did it: it doesn’t get simpler.

Does the incident raise any more complicated issues? No doubt the case will be made.

Liddle thought the trial of Dobson and Norris for the murder of Stephen Lawrence was unfair, and he expressed this view in the Spectator while the trial was in progress. No problem there, you may think, except that well-established and well-known English law forbids such opinionating in public while the justice process is under way.

It does so, not as a form of authority-inspired censorship, not to inhibit discussion about the justice system and not because the system doesn’t really trust jurors, but to protect the weak and the innocent. The law exists because defendants, their lawyers and others who cared about justice argued for it and won the argument.

Liddle knew this. Now he may disagree with the law, but in a democracy the normal course of action for people who want to change a law is to make the case for change rather than to break the law.

Equally, if he believes strongly that Norris and Dobson are victims of a miscarriage of justice he was free to make that case after the verdict. There are, sadly, plenty of miscarriages of justice and there are quite a lot of people who want to draw attention to them. With rare exceptions they do so within the law.

Does Liddle really disagree so fundamentally with the law on contempt that he feels the need to break it? Does he really care so much about the case of Norris and Dobson that he will break the law to support them?

If so we can respect his views even if we question his methods, and perhaps we can look forward to seeing him engage in further acts of civil disobedience in pursuit of his cause. We can also expect him to explain that his past actions were calculated and deliberate (though the Spectator might not be happy about that).

If, on the other hand, this was a casual act of arrogance by someone who knew he personally would pay no price for it, how surprised would we be?

Brian Cathcart teaches journalism at Kingston University London and is a founder of the Hacked Off Campaign. in 2000, he won the Orwell Prize for his book The Case of Stephen Lawrence. He tweets at @BrianCathcart