3 Oct 2013 | Europe and Central Asia

There was much raising of eyebrows yesterday when it was announced that Russia’s “International Academy of Spiritual Unity and Cooperation” are putting forward Vladimir Putin as a Nobel Peace Prize nominee. But who are the International Academy of Spiritual Unity and Cooperation.

A source suggests to Index that they are “a typical pseudo cultural organisation” that gets budgets for loyalty to Putin and is ruled by ex-Soviet nomenclature. But judging by this list of presidents, vice presidents, and Heroes of the USSR, they are very, very important people indeed. (Source)

Composition of the Management Board and the Academy

The President

Trepeznikov Shilov

First Vice-President

Gennady Zgersky,

First Vice-President

Alexander Leonidovich Manilow

First Vice-President

Topchiy Sergei Stepanovich

First Vice-President

Paul P. Petrik,

First Vice-President

Taras Shamba Myronovych,

The first vice-president

Sergei K. Kamkov.

Vice – President

Viktor Gorbatko – twice Hero of the Soviet Union (astronaut), B

Vice – President

Mikhail Tikhomirov – Advisor to the President of the Russian Olympic Committee

Vice – President

Aliyev Phase Gamzatovna folk poet of Dagestan,

Vice – President

Sergey Makarov

Vice – President

Malik – Ohanjanian Rafael Gegamovich – Branch Manager in Armenia

Vice – President

Todash Guinn, Head of the Representation in Japan

Vice – President

Yankovskaya Ludmila – Head of Representation in Ukraine

Vice – President

Bishop Vissarion – Head of Mission in Abkhazia, head of the Orthodox Church in Abkhazia,

Vice – President

Stoyan Topalov – Head of Representation in Bulgaria

Members of the Presidium

Sergei Shamba Tarasovich – Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Abkhazia.

Glebov Vladimir Vladimirovich – Academician of the Academy of Architecture.

Dadaev Gadzhievich Felix – People’s Artist of the USSR.

Antoshkin Nicholas T. – Hero of the Soviet Union.

Bepko Yegorov – Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (MFA).

Yuri Dubinin – Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (MFA).

Primakov Yevgeny Primakov – Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (MFA), President of the Chamber of Commerce of the Russian Federation.

Peter A. Makarov – Project Manager CNNS Russia.

Kabzon Iosif Davidovich – People’s Artist of the USSR.

Rogozhkin Nicholas E. – Deputy. Minister for the Interior Ministry, Interior Troops Commander of the Russian Federation.

Ivan Sergeyev – Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (MFA).

Alexander Golubev Titovich – Chairman of the RAF veterans’ organization.

Kuz’kina Galina – a journalist, deputy. chief editor of the magazine “Our Power.”

Valentin A. Prikhodko – gene. Director of the “Pride of Russia”.

Sergei Baburin, rector of the institute.

Novozhylov Valery Yu – Major – General of the Russian Federation Ministry of Internal Affairs of explosives.

Zalikhanov Michael Chukkaevich – Hero of the Soviet Union, deputy of the State. Duma

Samvel Samvel Grigoryan – Academician of the AHP.

Valentina Tereshkova – the pilot – cosmonaut.

Arthur N. Chilingarov – the hero of the Soviet Union, Hero of the Russian Federation, the deputy of the State. Duma.

Mesenzhnik Jacob Z. – Academician of the Academy of science and business.

Mikhail Vinogradov – Head of Federal Agency for Industry.

Aydarov Letcho Ayubovich – gene. manager of the “Larakas” in Moscow.

3 Oct 2013 | News

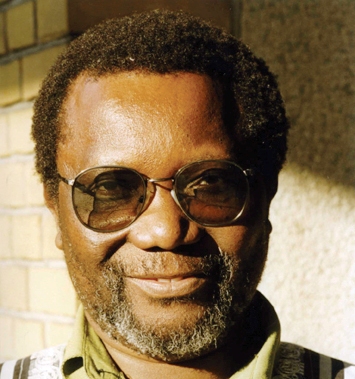

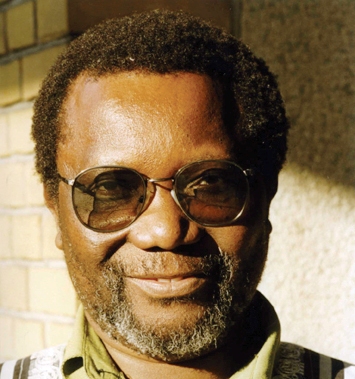

Born in Malawi in 1944, Jack Mapanje, one of Africa’s most distinguished poets, studied in England before returning to teach at the University of

Born in Malawi in 1944, Jack Mapanje, one of Africa’s most distinguished poets, studied in England before returning to teach at the University of

Malawi.

His first collection of poems, Of Chameleons and Gods, published in the UK in 1981, was banned in Malawi in June 1985 due to its being ‘full of … coded attacks’ on the ruling dictatorship of Hastings Kamuzu Banda. Two years later, in September 1987, he was imprisoned without trial or charge by the Malawian government.

Many writers, linguists and human rights activists campaigned for his release, including Harold Pinter and Wole Soyinka, and in 1990 he was awarded the PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award. Despite this international pressure, Mapanje served almost four years in Mikuyu prison, where he composed his second collection of poetry, The Chattering Wagtails of Mikuyu Prison, and most of his third collection, Skipping without Ropes. He was finally released in May 1991.

On His Royal Blindness Paramount Chief Kwangala

by Jack Mapanje

I admire the quixotic display of your paramountcy

How you brandish our ancestral shields and spears

Among your warriors dazzled by your loftiness

But I fear the way you spend your golden breath

Those impromptu, long-winded tirades of your might

In the heat, do they suit your brittle constitution?

I know I too must sing to such royal happiness

And I am not arguing. Wasn’t I too tucked away in my

Loin-cloth infested by jiggers and fleas before

Your bright eminence showed up? How could I quibble

Over your having changed all that? How dare I when

We have scribbled our praises all over our graves?

Why should I quarrel when I too have known mask

Dancers making troubled journeys to the gold mines

On bare feet and bringing back fake European gadgets

The broken pipes, torn coats, crumpled bowler hats,

Dangling mirrors and rusty tincans to make their

Mask dancing strange? Didn’t my brothers die there?

No, your grace, I am no alarmist nor banterer

I am only a child surprised how you broadly disparage

Me shocked by the tedium of your continuous palaver. I

Adore your majesty. But paramountcy is like a raindrop

On a vast sea. Why should we wait for the children to

Tell us about our toothless gums or our showing flies?

3 Oct 2013 | News

Zarganar is Burma’s leading comedian and an accomplished poet, writer, and director who throughout his career has used his artistic talents to draw attention to political repression in Burma.

Zarganar is Burma’s leading comedian and an accomplished poet, writer, and director who throughout his career has used his artistic talents to draw attention to political repression in Burma.

Zarganar was first arrested in 1988 following the pro-democracy demonstrations, in which he played a leading role. As reading and writing were forbidden in his cell in Insein Prison, he mixed dust from the bricks in his cell with water and wrote poetry on the floor, committing the poems to memory and sweeping away the evidence. He was freed after six months.

He was arrested again in 1990 while making jokes at a political rally, and was returned to Insein, where he spent five years in solitary confinement.

Following his release, he was increasingly involved in social activism and worked closely with international NGOs. During the ‘Saffron Revolution’ of 2007, Zarganar was one of the key figures to lead public support. This led to a further three weeks in detention.

Zarganar’s arrest in June 2008 resulted from his criticism of the Cyclone Nargis relief effort. He had personally organised support from the Burmese arts community and oversaw its delivery to the delta. He was angered by the neglect and corruption he encountered and spoke out about this in interviews. In November 2008, he was convicted of ‘public order offences’ and sentenced to 59 years in prison, later reduced to 35 years.

In late 2008, Zargana was moved to Myitkyina Prison in northern Burma, 1,500km from his family home. Zarganar was awarded the inaugural PEN/Pinter Prize for an International Writer of Courage in 2009. He was release from prison in October 2011.

Untitled

by Zargana

Translated by Vicky Bowman

It’s lucky my forehead is flat

Since my arm must often rest there.

Beneath it shines a light I must invite

From a moon I cannot see

In Myitkyina.

Listen to Index’s Free Speech Bites Podcast interview here

2 Oct 2013 | Azerbaijan News, News

An opposition protest in Baku, September 2013 (Image Demotix/Aziz Karimov)

The tone was set the day we arrived in Azerbaijan, 17 September 2013. Journalist Parviz Hashimli, was arrested and detained by officers of the Ministry of National Security after a raid on the office of newspaper Bizim Yol.

Hashimli is an influential journalist as the editor of Moderator.az website and chair of the Center for Protection of Political and Civil Rights. He was accused of drugs smuggling and the illegal possession of weapons. According to the Institute for Reporters’ Freedom and Safety (IRFS) in Baku, “it is unclear exactly what prompted the arrest of Hashimli and raid on BizimYol newspaper. However, some experts believe it was linked to a series of leaks reporting on developments in the state machinery, published shortly before his arrest on www.moderator.az news source.”

Human rights activists that we met believe that Hashimli’s arrest is yet another attempt to intimidate the press in the run-up to the October election. This week, the editor of Tolyshi Sado newspaper, Hilal Mamedov, was sentenced to five years in prison.

At least eight journalists are currently imprisoned in retaliation for their reporting on sensitive issues. This is the backdrop to Azerbaijan’s election next week, an election that is being fought in one of the least free countries on earth.

Journalists are not the only group affected by arrests under fabricated charges. Youth movements have been particularly targeted since March 2013. Index met with relatives of some of the seven NIDA members arrested last March and April for “drug possession” or “suspicion of inciting violence”. NIDA is a youth movement calling for more democracy in Azerbaijan. The seven members arrested were particularly active on social media and known for their criticism of the authorities.

On 19 September, we met former Index on Censorship award winner Rashid Hajili, who is a lawyer and chair of the Media Rights Institute. “Since 2003, the situation has gradually worsened,” says Hajili. While the human rights situation is deteriorating on the eve of the presidential elections, Hajili sees the situation as the result of a decade-long “shift toward authoritarianism”. Not only have the authorities of the country ignored their international commitments – such as decriminalising defamation – but they have adopted legislation imposing new restrictions on fundamental freedoms.

Rashid Hajili with his Index on Censorship Award (Image: Melody Patry)

In May, Azerbaijan’s parliament adopted regressive legislation extending criminal defamation provisions to online content. Azerbaijanis now face potential fines of up to AZN 1,000 (approximately USD $1,280), or prison sentences of up to three years for items they post online, including on Facebook. The chilling effect is so severe that individuals refrain from even “liking a friend’s controversial status”, says a young Azeri. “We are aware that social media are monitored,” she adds.

As the Aliyev regime tightens the screws, space for free expression is shrinking and prospects for free and fair elections grow slimmer. Three years after receiving Index’s Law and Campaigning Award, Rashid Hajili is still busy fighting repression against the right to freedom of expression in the country. The number of his clients prosecuted for being critical to the government keeps increasing. “There is very limited space for free expression,” says Hajili. “Many independent or critical voices go online, to online newspapers and to social media”. But the online space is not safe. While many in the civil society or international diplomacy have denounced criminal prosecutions for online publications, and intimidation of journalists, Azerbaijan routinely ignores criticism of its human rights record by international bodies.

Born in Malawi in 1944, Jack Mapanje, one of Africa’s most distinguished poets, studied in England before returning to teach at the University of

Born in Malawi in 1944, Jack Mapanje, one of Africa’s most distinguished poets, studied in England before returning to teach at the University of Zarganar is Burma’s leading comedian and an accomplished poet, writer, and director who throughout his career has used his artistic talents to draw attention to political repression in Burma.

Zarganar is Burma’s leading comedian and an accomplished poet, writer, and director who throughout his career has used his artistic talents to draw attention to political repression in Burma.