20 Sep 2017 | Greece, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The European Parliament is accused of censoring a series of political cartoons from Greece which were due to appear in an upcoming exhibition later this month.

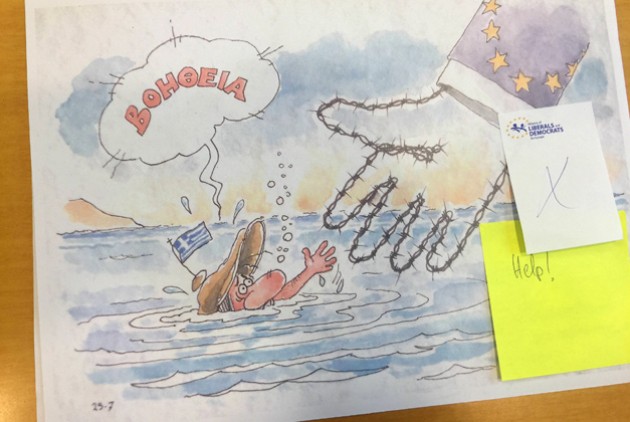

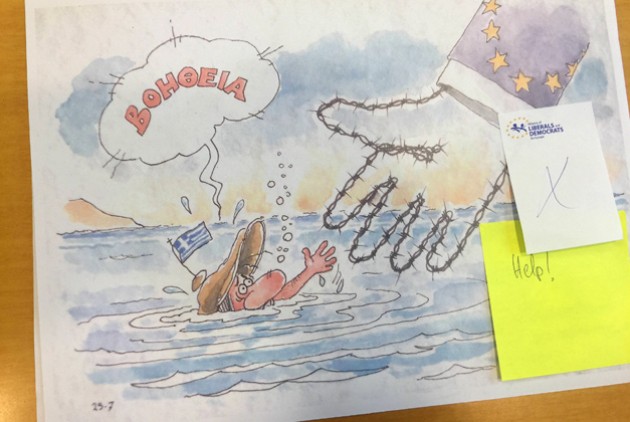

The exhibition, organised by an MEP from Greece and an MEP from France, aimed to present political and humorous sketches created by cartoonists from the two countries and published in the press on the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of the Rome Treaty. However, Catherine Bearder, a British Liberal Democrat MEP from southeast England, who is responsible for the cultural and artistic events sponsored by other members, decided to remove 12 out of 28 cartoons, all created by Greek cartoonists, claiming that the artwork contained “controversial content”.

Index on Censorship approached Bearder for comment but at the time of writing she had not replied.

According to the regulation of the European Parliament, all cultural events and exhibitions have to be checked so that “under no circumstances be offensive or of an inflammatory nature or contradictory to the values” of the EU.

The Greek MEP, Stelios Kouloglou denounced the “unprecedented” form of censorship by the European Parliament. “The content of the censored cartoons did not insult the values of the European Union in any way,” Kouloglou said in a press conference in Strasbourg on Tuesday, 12 September.

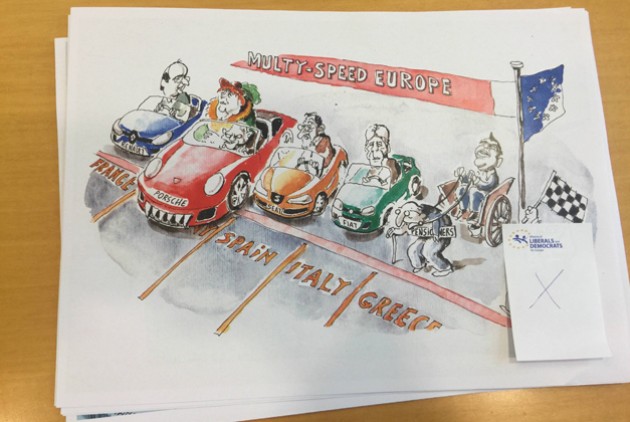

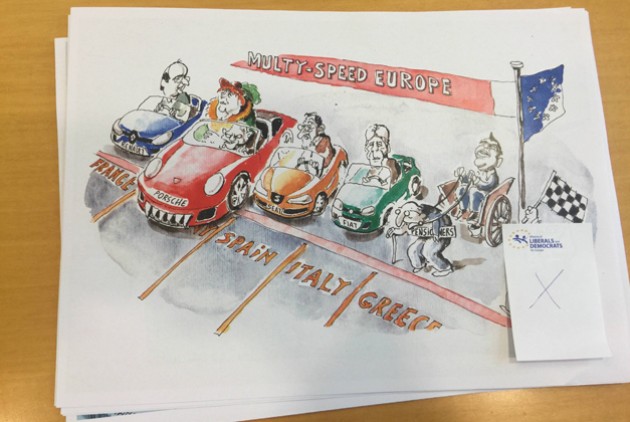

The 12 cartoons are critical of the EU and focus mainly on the way the EU – and especially Germany – dealt with the Greek crisis. One of the censored cartoons features the starting line for a race, with Germany in a Porsche sports car, Italy, Spain and France in old cars and Greece in a chariot being pulled by a pensioner.

Breader presented the upcoming German election as another reason to discard the 12 cartoons, although the exhibition is scheduled to take place after the election.

Breader presented the upcoming German election as another reason to discard the 12 cartoons, although the exhibition is scheduled to take place after the election.

“The right for artistic creation and freedom of expression are part of the European Union’s fundamental values. This arbitrary decision violates them” Kouloglou remarked in a letter of complaint addressed to the president of the European Parliament, Antonio Tajani.

The Journalists’ Union of the Athens Daily Newspapers also denounced the incident of censorship asking for the intervention of the European and International Federation of Journalists.

Credit: Stelios Kouloglou, MEP[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1505898132982-6897be5b-fada-1″ taxonomies=”5768, 1888″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

20 Sep 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Press Releases

Index on Censorship’s database tracking violations of press freedom recorded 571 verified threats and limitations to media freedom during the first two quarters of 2017.

Index on Censorship’s database tracking violations of press freedom recorded 571 verified threats and limitations to media freedom during the first two quarters of 2017.

During the first six months of the year: three journalists were murdered in Russia; 155 media workers were detained or arrested; 78 journalists were assaulted; 188 incidents of intimidation, which includes psychological abuse, sexual harassment, trolling/cyberbullying and defamation, were documented; 91 criminal charges and civil lawsuits were filed; journalists and media outlets were blocked from reporting 91 times; 55 legal measures were passed that could curtail press freedom; and 43 pieces of content were censored or altered.

“The incidents reported to the Mapping Media Freedom in the first half of 2017 tell us that the task of keeping the public informed is becoming much harder and more dangerous for journalists. Even in countries with a tradition of press freedom journalists have been harassed and targeted by actors from across the political spectrum. Governments and law enforcement must redouble efforts to battle impunity and ensure fair treatment of journalists,” Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom project manager, said.

Q1 2017

During the first quarter the MMF database registered several trends that can be recognised as acute challenges to media freedom. A total of 299 incidents were reported to the project by MMF correspondents and other journalists between 1 January and 31 March 2017.

Some European governments clearly interfered with media pluralism. Other governments harassed, intimidated and detained journalists. The net effect of these interventions have been to debase and devalue the work of the press and undermine a basic foundation of democracy.

Throughout Q1: one journalist was murdered; 42 incidents of assault were confirmed; there were 89 verified reports of intimidation; media professionals were detained in 69 incidents; 38 criminal charges and civil lawsuits were filed; and journalists were barred from reporting in 54 verified incidents.

The full Q2 report is available on the web or in a combined Q1/Q2 PDF.

Q2 2017

The crackdown on media freedom throughout Europe — even within those countries perceived to be more democratic — continued in Q2 2017. A total of 272 incidents were reported to the project by MMF correspondents and other journalists between 1 April and 30 June 2017.

While the number of reports recorded during the second quarter declined nearly 10 per cent from the first quarter, this does not indicate an improvement in the overall state of media freedom. The situation for journalists across Europe remained extremely concerning. For example, the number of arrests decreased during the quarter, but hundreds of journalists were in detention or were forced into exile. In addition, based on the severity of the second quarter reports, inhumane treatment of media workers actually increased.

Throughout Q2: two journalists were killed; 36 incidents of physical assault and injury were reported; 53 criminal charges and civil lawsuits were filed; 99 instances of intimidation, which includes psychological abuse, sexual harassment, trolling/cyberbullying and defamation, took place; journalists were blocked from covering stories 54 times; 20 legal measures were passed that curtail press freedom; and 19 works were censored/altered by the state or editorial teams.

The full Q2 report is available on the web or in a combined Q1/Q2 PDF.

For more information, please contact:

For further information, please contact Hannah Machlin, project manager, Mapping Media Freedom on [email protected]

About Mapping Media Freedom

Mapping Media Freedom – an Index on Censorship-lead project with partner European Federation of Journalists and Turkey-based P24, Platform for Independent Journalism, partially funded by the European Commission – covers 42 countries, including all EU member states, plus Bosnia, Iceland, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Norway, Serbia, Turkey, Albania along with Ukraine, Belarus and Russia and Azerbaijan. The platform was launched in May 2014 and has recorded over 3,300 incidents threatening media freedom by the end of Q2 2017.

Search reported incidents throughout Europe at https://mappingmediafreedom.org.

19 Sep 2017 | Events, Volume 46.03 Autumn 2017 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Free to air is the autumn 2017 edition of Index on Censorship magazine

Join Index on Censorship magazine for the launch of the autumn 2017 celebrating all things radio.

In conjunction with our friends at Resonance FM, Index will be broadcasting all evening on Tuesday 10 October, as we discuss the rebirth of radio and why it is so important to freedom of expression.

Special guests include Jamie Angus, deputy director of the BBC World Service Group, broadcaster and DJ Tabitha Thorlu-Bangura from NTS Live, broadcaster and sound artist Fari Bradley from Resonance FM and writer and broadcaster Mark Frary, who will also be running a short DIY podcasting workshop before the panel discussion.

We’re launching the magazine with its special report Free to Air: Why the Rebirth of Radio is Delivering More News at the iconic Tea Building in Shoreditch, home to digital product studio ustwo, our venue partners for the launch. Features in the latest magazine include a 98-year-old granny making grassroots radio in the USA, radio journalists in Somalia who brave danger to do their jobs and the Spanish comedians who make a television show about a radio station.

There will be drinks from Flying Dog Brewery, our freedom of expression chums and sponsors and we’ll be closing the evening with a DJ set from Resonance FM’s very own Nana Nicol.

6:00 – 6:30 DIY podcasting workshop, register for your free space via [email protected]

6:30 – 7:15 drinks

7:15 – 8:30 Panel discussion

8:30 – 9:00 DJ set from Nana Nicol

Many thanks to:[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95760″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://resonancefm.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”80918″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://uk.sagepub.com/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”95897″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://ustwo.com/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Tuesday 10 October 18:30 to 21:00

Where: ustwo London, 62 Shoreditch High Street, London E1 6JJ

Tickets: Free. Registration required via Eventbrite

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Sep 2017 | Europe and Central Asia, Italy, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Italian journalist Paolo Borrometi.

Italian journalist Paolo Borrometi was forced to move to Rome from Sicily because of threats he was receiving connected with his reporting on organised crime. Borrometi’s story is far from unique. He is one of the 20 journalists currently under police escort in Italy.

In May 2014, Borrometi was beaten by two hooded men near his home after he asked citizens to report any relevant information to investigators about a two-year-old murder. The assault did not deter his reporting on organised crime, nor did a vandalism incident in which the front door of his parent’s home was destroyed in an arson attack.

Despite being forced to relocate to Rome for security reasons, Borrometi’s work uncovering mafia activities continued, as did the almost constant intimidation he faced. This summer a group of unidentified people raided his home, stealing computer hard disks and a series of documents related to his investigations.

The Italian Interior Ministry released official figures of the number of journalists under police protection for the first time in June 2017 to highlight the growing phenomenon.

Borrometi works as editor-in-chief of a local webzine, LaSpia.it, and is a contributor to several other media outlets as a freelancer. Without a regular salary, he needs to keep publishing to earn a living. Many Italian journalists are in the same position financially. According to Nicola Marini, a board member of the Association of Journalists (Ordine dei Giornalisti), which monitors the ethical conduct of journalists, eight out of ten Italian journalists earn less than €10,000 per year.

Beppe Giulietti, the president of the Italian journalists’ trade union FNSI, recounted a conversation he had with Borrometi after the interior ministry decided to put him under escort: “He was worried this situation could interfere with his job.” For freelance reporters a mafia threat does not just affect personal safety, it creates a serious obstacle to performing their jobs. Conducting a simple interview becomes a lot harder when the reporter is followed by a group of policemen. But without them, Borrometi’s life would be in serious danger.

“Compared to the past, the current situation for journalists shows fewer mafia killings,” Giulietti told Index on Censorship. “But sometimes physical threats are not necessary.”

Indeed the economic situation for Italian journalists is harsh and, as Giulietti said, “a defamation lawsuit could be as lethal as a bullet”. Many journalists stop working on investigations because of the risk of lawsuits. If they were sued they wouldn’t be able to afford the economic risks. The result is self-censorship.

Many lawsuits have no legal basis. The Italian permanent observatory on threats to journalists, Ossigeno, estimates that one-third of defamation claims in Italy originate from allegedly mafia-connected people or lobbies.

These cases are often civil and the plaintiff demands enormous amounts of money even though the claim is created as a pretext and the alleged damage is minimal. Quite often the aim is only to intimidate.

The financial fragility of journalists has led to a phenomenon that Alberto Spampinato, president of Ossigeno, calls “the Italian paradox”. Italy has a long history of journalists killed by mafia-affiliated killers, especially during the late 1980s and 1990s. This situation brings growing attention to the link between freedom of information and organised crime.

After an initially strong reaction from the public, things usually turn silent. Ossigeno, which was founded in 2007 after three journalists and writers – Roberto Saviano, Lirio Abbate and Rosaria Capacchione – were put under police escort, aims to put a continuous spotlight on threats to journalists. The Italian public is aware of the problem but politicians are not reactive, according to both Spampinato and Giulietti. Freedom of information, especially related to the nexus between organised crime, politics and corruption is constantly under siege.

The Italian parliament is currently discussing a new law to avoid the complete transcriptions of the intercepted conversations, “but no one is taking care of the lawsuits based on weak grounds which are only made to intimidate journalists (in Italian defined as “querela temeraria”), although the trade union has already highlighted this problem,” Giulietti said. The president of the journalists’ trade union wants to stress how politicians are focused only in amending the system not to publish news that could affect them, rather than amending a concrete vulnus in freedom of journalists.

According to the latest Ossigeno report, reporting on organised crime is harder for people who live in remote places. Local journalists often feel pressure from local officials and criminal syndicated, Spampinato explained.

For example, in Rho, a small town in the outskirts of Milan, the newsroom of the local newspaper, Settegiorni, was vandalised by a group of unknown people three times in three months, the latest incident occurring on 3 September. The newspaper has been working on an investigation about the presence of the criminal syndicate ‘Ndrangheta in Rho, according to editor-in-chief Angelo Baiguini.

Though politicians are slow to act, some parts of the Italian parliament are monitoring the situation. The Parliamentary Anti-Mafia Commission set up a Committee on Mafia, Journalism and Media. In August 2015 the Committee highlighted that there are southern Italian regions where media publishers have an “opaque management”, involved in judiciary case, even for alleged external support to mafia syndications. Obviously they are willing to stop muckrakers digging into their businesses.

Up until now, there have been no solutions to this problem from a legal perspective. This leaves many good reporters at risk and makes in-depth reporting about organised crime ever more difficult. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1505821805138-929619f7-ec4b-9″ taxonomies=”193, 6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Breader presented the upcoming German election as another reason to discard the 12 cartoons, although the exhibition is scheduled to take place after the election.

Breader presented the upcoming German election as another reason to discard the 12 cartoons, although the exhibition is scheduled to take place after the election.

Index on Censorship’s database tracking violations of press freedom recorded 571 verified threats and limitations to media freedom during the first two quarters of 2017.

Index on Censorship’s database tracking violations of press freedom recorded 571 verified threats and limitations to media freedom during the first two quarters of 2017.