This article first appeared in Volume 54, Issue 3 of our print edition of Index on Censorship, titled Truth, trust and tricksters: Free expression in the age of AI, published on 30 September 2025. Read more about the issue here.

In his book What is Free Speech? The History of a Dangerous Idea the historian Fara Dabhoiwala aims to show how free speech, once viewed as both hazardous and unnatural, was reinvented as an unalloyed good, with enormous consequences for our society today. Its origins and evolution, he argues, have less to do with the high-minded pursuit of liberty and truth, than with the self-interest of the wealthy, the greedy, and the powerful. Free speech as we know it, he writes, is a product of the pursuit of profit, of technological disruption, of racial and imperial hypocrisy, and of the contradictions involved in maintaining openness while suppressing falsehood.

I was rather sceptical about taking such a bleak view. Growing up behind the Iron Curtain, with unrelenting state and party propaganda, a right to speak and think freely has always been, to me, a foundation of free society – a vaccine against tyranny. Just like journalism, I have always viewed free speech as a way to speak truth to power, rather than the other way around; to see a variety of perspectives, develop empathy and understanding of different viewpoints, disagree civilly and thus reduce polarisation, ultimately leading to healthy societal development.

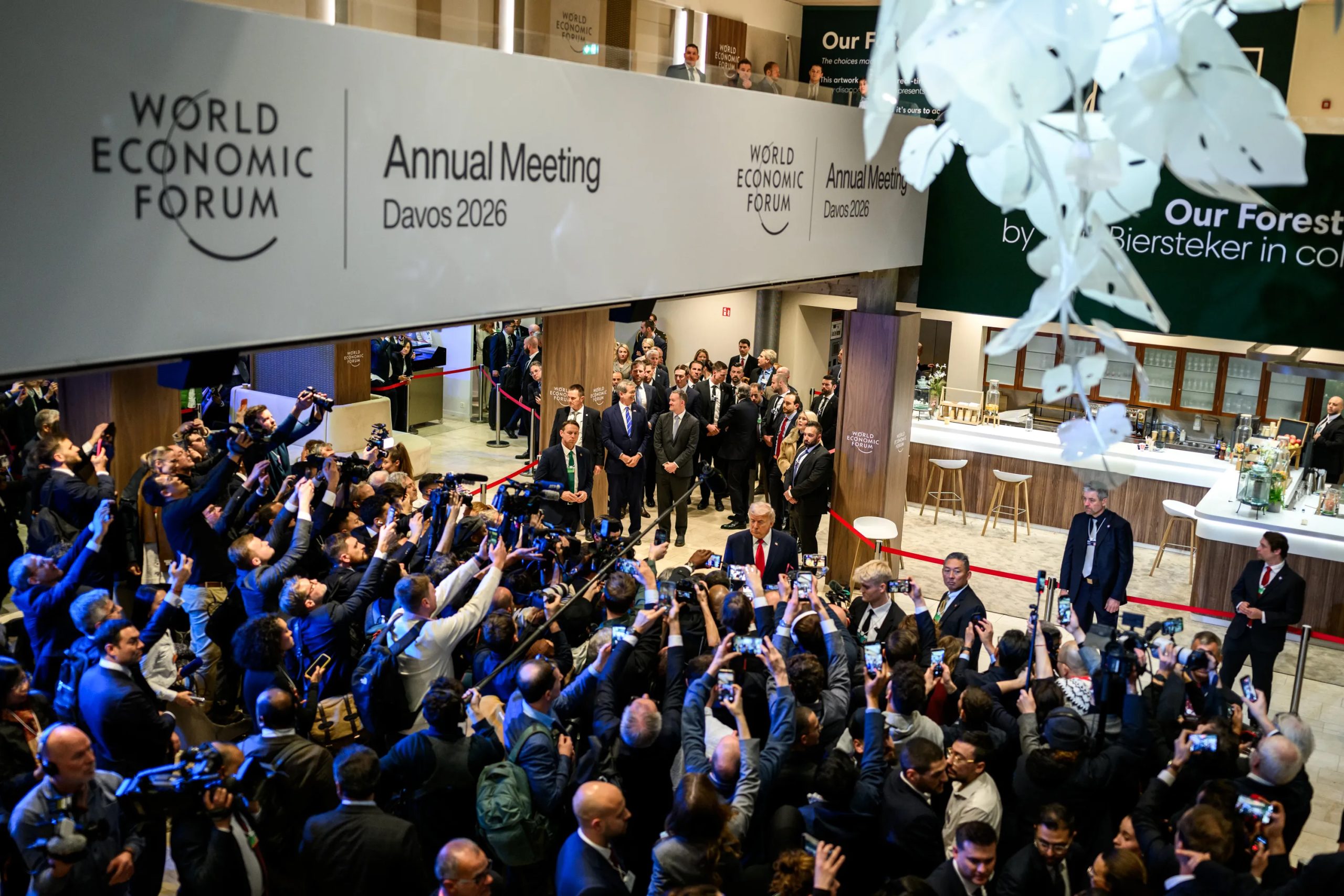

After more than 20 years in the West, and observing recent cultural trends, I have to admit that my original view was somewhat idealistic. First, as Dabhoiwala rightly points out in his book – the right to free speech has never been available to all or distributed equally. It is not possible to do justice to the free speech discussion without seeing it through the lens of power, who has a voice and who doesn’t? The fact that free speech is such a polarising issue today ultimately goes back to a single question – who controls the narrative? When Elon Musk claims to be “a free speech absolutist” defending the right to speak truth to power, he seems to forget that he himself is the power: a billionaire owner of a platform which controls the algorithms of what content its users see, and what gets prioritised. This is less about the “right to free speech” but more about rejecting any regulations that exist in the real world. Meta, which controls Facebook, Instagram and Threads, is no different.

In the current climate of cancel culture and cultural boycotts, it would be good to focus on concepts such as institutional responsibility and their duty. When cultural institutions, film and literature festivals choose to steer on the side of caution for fear of attracting protests, or courting controversy, they fail not only themselves and the artists who trust them, but the public too.

Take two Canadian film festivals which last year cancelled controversial documentaries about the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Organisers opted to pull the films for the fear of attracting protests. They resorted to censorship, instead of prioritising the right of the public to see different perspectives and practise their own critical thinking. Institutions need to have a backbone to stand up for their programming and curatorial independence and autonomy. Films, literature, music and art are there to spark debate and conversations, not simply to follow any particular political agenda.

In 2017 in Zurich, where I live, one of the leading theatres announced an interesting and provocative experiment – The New Avant-Garde. It was supposed to be a discussion between right-wing nationalists, libertarian activists and members of the liberal democratic movement.

According to Jörg Scheller, an art historian who teaches at Zurich University of the Arts (Zhdk) and who was supposed to take part in the discussion, the idea was to discuss the meaning of terms such as “liberal,” “right”, “conservative”, and “progressive” from the perspective of the panel’s participants. Public debate is a necessity, the organisers argued, as everything else just leaves those rightly or wrongly excluded to radicalise themselves in their own filter bubbles. However, as the pressure on the institution grew from its own peers opposed to platforming right-wing voices, the theatre gave way and cancelled the discussion.

When public institutions and academia cede territory, market forces move in – sometimes with questionable motives and results. Californian start-up Jubilee Media went viral for hosting heated debates with subjects like Flat Earthers vs Scientists, with Mehdi Hasan recently featuring in one titled 1 Progressive vs 20 Far-Right Conservatives which racked up 10 million views within a month of being posted on YouTube.

The format is deeply flawed. Instead of intellectual honesty and stimulation, it is a lot of fast-paced shouting over each other with participants so entrenched in their own views that they seem to perform them for their own audiences, rather than genuinely engaging with the opponent. There is no shortage of controversial views on offer, with Hasan saying blankly at one point that he doesn’t debate fascists. Jubilee Media’s CEO Jason Y Lee, meanwhile, has argued that his vision of this civil discourse is “Disney for empathy”.

But should it really be left to market forces to provoke understanding and foster human connection?

“People hardly ever make use of freedom of thought,” Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard wrote in his journals. “Instead, they demand freedom of speech as a compensation for the freedom of thought which they seldom use.” Can one truly exist without the other? Free speech as an end principle in itself is a concept with little value when not accompanied by a genuine need for truth-seeking and free thinking.

It is true that tolerance of opposing views is a virtue and a necessity in any democratic society. Only by trying our ideas on each other can we figure out what to believe, what to criticise and how to progress towards the truth – both individually and collectively. Maybe instead of talking of “the right to free speech” and “censorship” as the two default settings, we should be asking ourselves how, by exercising our right to free speech, are we contributing to the societal good?

Ultimately, everyone’s intellectual freedom is society’s immune system. As Soviet dissident physicist and human rights defender Andrei Sakharov said beautifully back in 1968: “Human society needs intellectual freedom – freedom to receive and disseminate information, freedom of unbiased and fearless discussion, and freedom from the pressure of authority and prejudices.”

Such triple freedom of thought is the only guarantee against the infection of the people with mass myths which, in the hands of cunning hypocrites and demagogues, easily turns into a bloody dictatorship. This is the only guarantee that a scientific and democratic approach to politics, economics and culture will work.”