Banned Books Week UK was revived and celebrated across the nation recently, and it spawned an important conversation in Scotland about the conflict between inclusivity and intellectual freedom.

I headed to Scottish Parliament for an event run by CILIPS (the leading professional body for librarians in Scotland), sponsored by the SNP MSP Michelle Thomson. The discussion in question: libraries, intellectual freedom and culture wars.

How do librarians create a collection that is welcoming to their community, and balance it with books that challenge ideas or might be unpopular? There are questions to ask about intellectual freedom, but also moral obligations. What to do, for example, if someone walks into a library and wants to see a copy of Mein Kampf?

“At times of polarised views, it’s vital that we protect intellectual freedom,” said Shelagh Toonen, an award-winning school librarian and the vice president of CILIPS.

She was clear – libraries should have full control over their collections and access. They already look at the appropriateness of books for particular age groups, and the whole aim of a school library is to foster curiosity and resilience.

Sat beside Toonen was Cleo Jones, the former CILIPS president and libraries development manager for City of Edinburgh Council. She described how there’s recently been a strong push for developing knowledge around equality, including anti-racism training for staff, and she’s seen a positive impact. But there can be a tension with intellectual freedom. Staff need training around this too, she said.

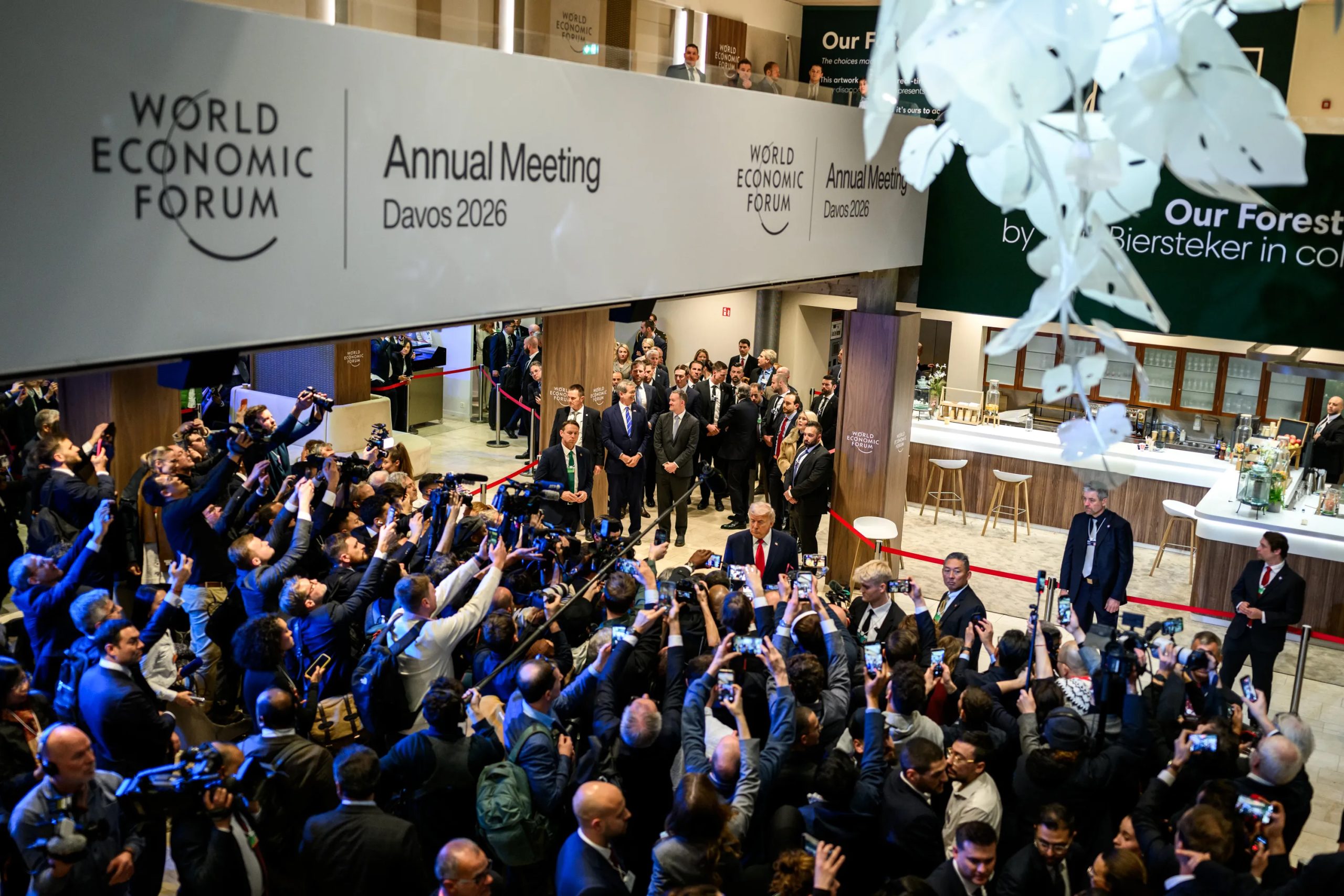

The Dear Library exhibition at the National Library of Scotland. Photo: Katie Dancey-Downs

Being a librarian was once considered a non-political role. Certainly, in the Dear Library exhibition just a short walk from Parliament in the National Library of Scotland, all the librarian stereotypes are on full display – a librarian action figure wearing glasses, a modest outfit and finger poised in the shush position, for example. But today, this role has suddenly become highly political, according to the panel. Managing sensitivities is a tough job, and is only getting tougher.

Steven Buchanan, professor of Communications, Media and Culture at the University of Stirling, put this into perspective with a discussion on book challenges in both the USA and the UK. He described how staff are being put under enormous pressure and are worried how things could escalate. Toonen and Jones have both been at the sharp end of this.

“It happened to me in my own school. A parent put in a letter of complaint because I had the book,” Toonen said of British writer Juno Dawson’s This Book is Gay, a book written for young people about the LGBTQ+ experience, and which has been one of the most banned books in the USA. Index research found that it has also been removed from some schools in the UK.

“If we remove books from our shelves how are young people going to see themselves represented?” Toonen asked, adding: “Two young people have come out to me in the school library, because it’s a safe space.”

For Jones, the event that caused a public stir was a drag queen story hour reading that her library held online during the Covid-19 pandemic. She described a staggering level of abuse directed towards staff, which mostly came from the USA.

“The number of positive comments far outweighed the negative, but three to four years later we’re still dealing with the fallout,” she said. They are still receiving letters, still instructing lawyers and some people involved in the event got major threats, she said.

Jones described how they had checked thoroughly that the drag queen was indeed a children’s entertainer. But that did not protect them from attacks. With so much time spent navigating the aftermath of a culture wars clash, Jones is concerned about the message this sends to librarians considering hosting similar events, and that they may well be put off. Her advice to fellow librarians – do all your checks (as she did), and then be completely transparent about this work, up front.

Challenges to collections have been easier to resist, she said. The more difficult and complicated fight is public spaces and displays, as the drag queen story hour lesson perfectly illustrates.

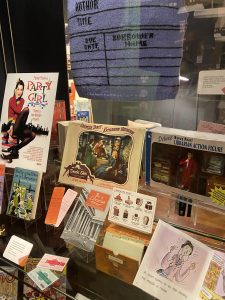

So too does an example from the National Library of Scotland, in the exhibition Dear Library. The display has been at the centre of a recent culture war clash, when the book The Women Who Wouldn’t Wheesht was not included, despite garnering enough votes – four – to be included as one of Scotland’s favourite books for the purposes of the exhibition. The book, a series of essays, is written by gender critical women detailing their political fight against the SNP leadership and the Scottish government which tried to introduce gender self ID laws (eventually blocked by Westminster). The book was still available in the library’s reading room, but deliberately left out of the exhibition due to staff concerns that it could cause harm.

Photo: Katie Dancey-Downs

The library faced a backlash for the decision which we wrote about at Index and later added the book to the exhibition. It is now there, on a double-sided row of shelves inviting people to look at the books, beneath front-facing copies of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting and Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The debate about sensitivities in library collections is clearly going nowhere, and the clash between trans rights and gender critical voices is a particularly polarising issue, especially in Scotland.

Challenges to free expression are nothing new. The difference now, the panel argued, is the rise of social media fuelling the culture wars. Suddenly, someone far away can learn about a decision in a library in Scotland.

“It feels heavier now,” said CILIPS president David McMenemy, and that’s because of social media.

Campaigns for books to be banned in the UK have been less organised than in the USA, where co-ordinated right-wing groups like Moms for Liberty have taken the lead. But Alastair Brian, the fact-checking lead for Scottish investigative journalism platform The Ferret, believes it is only a matter of time before that changes.

“There are certain groups in Scotland trying to put pressure on,” he said, specifically around books that the groups consider ideological. “In the US the way this has been applied is by singling people out. That definitely has a huge chilling effect.”

The question now is how libraries navigate these challenges, which are certainly not going away, and more likely will increase. Librarians need advocacy and funding, the panel said, and for MPs to oppose obvious censorship attempts.

Beyond this, McMenemy added, there is a problem with politicians finding profit in making everyone angry, and it is something he urged them to stop embracing.

Ultimately, the panel saw a strong need for open conversations where intellectual freedom, culture wars and sensitivities clash – and that means listening, as well as speaking. As Toonen told the room: “The best solution is always dialogue.”