6 Aug 2014 | Academic Freedom, News, United States

(Photo: Georden West)

A women’s university considered to be one of the most restrictive on transgender issues in the US is reconsidering its approach.

Rated as the strictest of any US university on transgender policies by the Chronicle of Higher Education, Hollins University currently forbids students from making any legal or biological step toward becoming male.

But a university official says the school is considering the addition of gender-neutral bathrooms to make the campus more welcoming and to support its students on the transgender spectrum.

Founded in 1842, Hollins University has attracted many now famous names including writers Annie Dillard and Margaret Wise Brown, US Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey and White House correspondent Ann Compton.

However, in the past few years its restrictive policy on the retention of transgender students has attracted national attention from activists and academics.

The current policy states that any student who “’self identifies’ as a male and initiates any of the following processes: 1) begins hormone therapy with the intent to transform from female to male, 2) undergoes any surgical process (procedure) to transform from female to male or 3) changes her name legally with the intent of identifying herself as a man,” will not be allowed to graduate from the university. After substantial criticism, Hollins agreed to re-evaluate its policy and drafted a new version in 2013. The current policy also maintains the university’s position against allowing female-to-male students and adds that any student who chooses to undergo sex reassignment “will be helped [by university officials] to transfer to another institution.”

The issue of gender-neutral spaces has become increasingly contentious and polarising with the emergence of a new transgender-equality group on campus called EqualiT*. Its appearance was marked by mysterious flyers in bathroom stalls and on announcement boards calling for the addition of gender-neutral bathrooms. Soon a blog and a Facebook page also appeared, and the group began to stage events, including a candlelight vigil to commemorate Transgender Awareness Day. Due to the sensitive nature of the organisation, the group has remained mainly anonymous in hopes of protecting its transgender members. Some students fear that, if exposed, transgender students will lose their scholarships or be expelled from the university. The university has not taken any action against students who are legally and biologically female, but some students say they self-censor because they are worried about what may happen.

With a student population of less than 600, low retention rates and a high-priced tuition cost of over $46,000 per year, critics question whether the university can afford to alienate any portion of its student demographic.

The forced removal of transgender students from Hollins presents not only financial and academic challenges but a threat to students’ safety. Forty-five per cent of transgender university students in the US reported experiencing verbal, physical or sexual abuse due to their gender identity according to a 2011 study by the National Center for Transgender Equality. Many transgender students attending all-female institutions regard the environment as safe and welcoming and fear for their safety in transferring to a coeducational environment. A study in 2006 revealed that one in twelve transgender people is murdered in the United States, and many more experience severe verbal harassment and physical violence.

“I believe creating gender neutral safe spaces should be at the forefront of the actions Hollins is taking right now,” said Cal Thompson, a transgender student who graduated in the spring of 2014. “Everyone needs a safe space for personal business. We don’t want to use the gendered bathrooms just as badly as the cisgendered don’t want us.”

Despite the relative safety transgender students feel at Hollins, students still find the university a challenging place to explore individual gender identities. Perhaps one of the most substantial of these challenges is in the lack of gender-neutral spaces, specifically bathrooms. Because of the requirement for students to remain female during their time at Hollins, students who identify as transgender are prohibited from using the men’s restroom.

“Using the bathroom at Hollins was uncomfortable,” said Lee Collie, a 2013 graduate, known as Leanna during his time at Hollins. “Even if you flip the sign to ‘male’ when you walk in, girls walked in all the time and said, ‘Oh, it’s just Lee,’ which meant that they didn’t really see me as a male.”

Hollins’ Dean of Students, Patty O’Toole told Index, “As we continue to renovate our facilities, when appropriate we are considering developing gender-neutral bathrooms.” With regards to facilities in residence halls, students in each community can collectively determine facility-usage and associated language, O’Toole said. Bathroom usage in residence halls is indicated by a paper sign for each hall’s bathroom, which can be flipped over to indicate different users. Thus, some facilities may be labelled with “men” and “women,” while others may use “residents” and “guests.” No other official steps have been taken to utilise gender-neutral language.

A number of students disagree with the student organisation’s position, including current student Deborah Birch, class of 2016. “I don’t think that there should gender-neutral bathrooms on campus. You apply to Hollins knowing that it is an all-women’s institution. If want to change your biological make-up to transition from female to male, you should choose to attend another institution.”

Though transgender graduate Lee Collie likes the idea of gender-neutral restrooms, he also worries about respecting the larger campus community, specifically those with opposing ideals. “I would probably limit them to the dorms or specific floors, because we have professors and visitors who may not feel comfortable.”

Hollins is not the only US institution struggling over whether it should create gender-neutral bathrooms. Recently Illinois State University has attracted media attention through its decision to change its family bathroom to an all-gender bathroom. Although the change was not specifically requested by any students or faculty, ISU officials made the change in efforts to remain proactive and to promote inclusivity among all members of campus. Over 150 universities across the United States have instituted similar changes in campus facilities, including New York University, Ohio State University and UCLA. Even fellow women’s universities like Smith College in Massachusetts and Agnes Scott College in Georgia have begun to embrace the issue, with the addition of gender-neutral restrooms and more progressive policies.

Collie, a former vice president of the university’s student government association, stated that the policy at Hollins may be strict, but he is glad that Hollins has a policy and acknowledges the existence of transgender students on campus. Other women’s universities have yet to adopt any policy on the matter.

Dean of Students, Patty O’Toole explained that the 2011 policy was originally created by the university’s Board of Trustees in response to students on the transgender spectrum who were seeking a written policy. “Hollins wanted to support those students. The focus of the policy is not strictness but clarifying our institutional mission.”

Collie supported the university’s actions and its mission as a women’s institution, despite the personal challenges he faced, and related the support and camaraderie he experienced at the university. “Hollins has never punished me for being or identifying as male. It isn’t that they’re trying to stop someone from being who they really are, but it is Hollins standing true to itself as well.”

This article was published on August 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Apr 2014 | Academic Freedom, News, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Photo: Shutterstock)

At the University of Bristol the stagnating number of female academics in multiple degree subjects has become an increasingly important and concerning issue. Over 65.4% of Bristol students, according to my March 2014 survey, perceived a noticeable imbalance of female to male lecturers. I agree. My research led me towards an obvious concern for Bristol students: gender inequality of academia in all subjects.

With The Independent reporting that 63.9% of female undergraduates are leaving universities with “good” degrees, a lack of visibility of female academics at the University of Bristol — especially in the more scientific faculties — is in stark contrast to the number of undergraduates in the same subjects. More and more articles are appearing asking “Where are the men?” seeking to discover why the gender gap of undergraduates is weighted in women’s favour, but few have even commented on the fact that women are still struggling for visibility as academics. Women are avoiding the academic world and important questions must be asked about whether this is evidence of institutional laziness on the part of universities.

A recent Commons Report titled “Women in Scientific Careers” (focussing solely on the topic of academia) found the gender diversity – or lack of it – in senior academic positions in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) “astonishing”. This conclusion of surprise is certainly supported by the Bristol experience: only 19% female Biology academics and fewer than 7% female Chemistry academics. Science students are beginning to question the gender gap at an academic level and why in 2014 it still remains an issue for women to break into STEM academia. One biology student commented: “I’m in my second term of University and I’ve yet to be taught by a woman. Representation is important and it’s worrying that female undergraduates might be less inclined to pursue an academic career.”

Universities are attempting to improve the imbalance in STEM departments with processes such as the Athena Swan awards. However, the School of Chemistry at Bristol holds a Bronze award for “promoting gender equality” despite having fewer than ten female academics in one of the largest departments at Bristol. The bar seems quite low. This doesn’t mean there isn’t a tangible appetite to tackle inequality in academia head on, it just seems that there has been little visible progression, simply supplementary reports and promises to improve.

Many female academics such as Athene Donald, professor of experimental physics at the University of Cambridge, have expressed disappointment with the Commons Report mostly due to it appearing to provide nothing more than “superficial recommendations”. I agree with Donald when she suggests more “drastic action” to tackle the current gender norms in university departments, without a vocal and aggressive protest calling for more inclusive hiring strategies. “There is a long, long way to go but all parts of the system need to be addressed if we are going to get past the stage of mere astonishment,” Donald wrote in February. We need to involve all levels of education; if women aren’t being encouraged equally at all stages of schooling then fixing the top level of academia will do little to fix the imbalance.

Personally, it’s been my experience with the history department at Bristol that has sparked this article. Why in a subject such as history with an equal amount of male and female undergraduates are there only 29% female academic staff? Having so few women lecturers in history when both genders are so equally matched at undergraduate level causes students to wonder if the higher jobs remain a boys’ club even in 2014.

Lynne H. Walling, head of pure mathematics at University of Bristol, has experienced more than her fair of sexism on her route to the top of her profession. Maths stereotypically has always been seen as a masculine pursuit and women have often been excluded or stymied in their interest. “More and more women do math, but we can hardly find female mathematicians who keep on researching the field.” She commented in interview with Somin Kim: “Only a few speakers at academic conferences are women, and sometimes none. Women feel that they don’t fit in the mathematical society and this is the hardship to continue their research.” Representation has always been a core issue. Without at least an approximation of gender equality among lecturers, female students are less like to dream to achieve. There isn’t an absence of female curiosity or intellect, there’s a lack of a platform.

But does a mismatch between women students and male lecturers actually impact free expression? At an undergraduate level the gender of their tutor seems to greatly impact female students. It becomes an issue of their future career as many women are told by those in academia that their gender is a weakness in the fight for research funding. No wonder women are half as likely to choose academia as a preferred career than men. Penelope Lockwood investigated whether the gender of career role models affected university students and she conclusively proved that women are more greatly motivated when inspired by the women in their chosen career, not the men. This is because the female students understood that their role model had surmounted and survived gender-specific challenges that they anticipate combatting in the future. They decisively empathise better with a female tutor.

Without an equal amount of female lecturers and tutors, female students are hindered in their progression through academic ladder. We need female lecturers teaching at an undergraduate level on an equal basis with men otherwise young women will continue to find the idea of achieving equal academic freedom with men in their subject simply unachievable. It’s a cyclical system: a minority of women teach, a minority of women become academics. Freedom of expression in academia involves an equal standing at all levels, and if we’re teaching equality at undergraduate level we need to clear the career path of gender obstacles for women from the grassroots up.

It’s obviously a more complex topic than can be covered in my brief assessment but the debate needs to be breached, universities need to answer questions about their hiring process and work together to close any forms of gender imbalance that still exist in higher education – including the wage gap. The statistics referred to above appear to support the conclusion that women are still experiencing sexism, especially when applying for jobs in STEM departments.

Universities would be well advised to address the issue swiftly so that the gender balance of academic, at the very least, reflects the gender balance of their undergraduates. Research support gender equality, so why aren’t universities?

This article was posted on 15 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Apr 2014 | News, Venezuela, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Image: Sergio Alvarez/Demotix)

Like other countries, Venezuela’s young are eager to explore the world. Every opportunity to learn becomes important in the formation of the young mind. In Venezuela, a crippled education system prevents normal development. While the well-born go to private schools and have access to every benefit, the mass of Venezuela’s students confront an educational system that tells them: “You can’t but you tried.”

The most embarrassing and painful thing about the deplorable state of the country’s schools is the level of the government’s indifference. Though the government of Nicolás Maduro offers programmes like “Simoncito”, “Mision Ribas” and “Mision Robinson” these is basic education that doesn’t adequately prepare students to pursue higher studies. The programmes seem to condemn the disadvantaged among Venezuela’s population to a remedial existence. If some of these children make it to higher education, the odds are stacked against them and their families.

In the end, it all comes down to money. Venezuela needs to spend more to let students be students. But with foreign reserves short, all but national priorities are left off the funding list. Every area of science instruction needs improvement. Budgets are not even close to covering the costs of labs, let alone providing learning aids or even actual textbooks. A prize-winning robotics team at Caracas’ Universidad Simon Bolivar works with outdated electronics that are often patched together. When the team wanted to take part in an international competition, they were denied assistance — meaning just a few of the team could do it because that was all they could afford to pay out of their own pockets. Another group, which took part in the Latin American conference of the model UN, found themselves staying in primitive conditions in Mexico because they were denied dollars, the currency they needed to pay bills. Despite the discomfort, the group won six awards.

Even with the obvious deficiencies in education, Venezuela has a large population of well-prepared professionals across a wide spectrum of expertise. But based on political affiliations, these people cannot work for the development of the nation. No wonder Venezuelans have begun to leave the country in search of a better future for themselves and their families. This exodus is manifesting itself worst of all among teachers. The ramshackle education system can ill afford this brain drain. But, again, it’s understandable when even those with advanced degrees from internationally respected institutions earn less than approximately £40 per month. When the government’s own basic food basket is priced at nearly £200 per month, it’s impossible to support a family without second or third jobs. Under strict rules, teachers are not allowed to apply for the loans that could support home or car ownership. In effect, teachers are sentenced to live with relatives for life. Yet they continue to teach out of love for the craft with the hope they they can raise a new generation of Venezuelans who can think for themselves and question dogma. Without them, the youth of Venezuela would be lost.

In recent interviews, the educational minister Hector Rodriguez said: “We are not going to take you out of poverty for you to go and become opposites.” His statement meant that Venezuela’s students should understand that their wings are already clipped and any dream of progress or improvement is invalid.

The government’s approach to education aims to make Venezuelans think it has the absolute truth and will decide what’s right for students. The lower classes won’t have any choice but to believe what they are told.

After 15 years Venezuelans have become accustomed to waiting for the government to wave a magic wand to provide what they need. The sense of personal responsibility now seems lost. Effort doesn’t deliver results, so Venezuelans don’t try. It’s an indirect way for the government to choose a person’s destiny.

At the same time, scarcity – and not just in an educational sense – is the new normal. Everyday basics like toilet paper, coffee or cooking oil are the subjects of long hunts that lead to the back of an equally long queue. Hospitals cancel operations for lack of supplies and cancer patients miss treatment for lack of medicine. And even though the government’s late March devaluation of the bolivar will fill the shelves in the shops, the average Venezuelan will be unable to afford the supplies.

For the government, scarcity is just a glitch — just like the blackouts when “iguanas eat the cables” – and not because the energy minister is not doing his job.

It’s impossible to walk down streets without being paranoid — one eye on the road and the other keeping watch of everything around you. On average 48 people are murdered in the country every day. Venezuelans can be beaten and robbed with no recourse to justice because the police and the criminals are often in partnership.

The Bolivarian Revolution was supposed to bring improvements, but the lack of daily essentials and a robust education system leads one to the conclusion: The basement has a bottom.

This article was posted on April 7, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

26 Feb 2014 | Academic Freedom, Comment, Guest Post, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

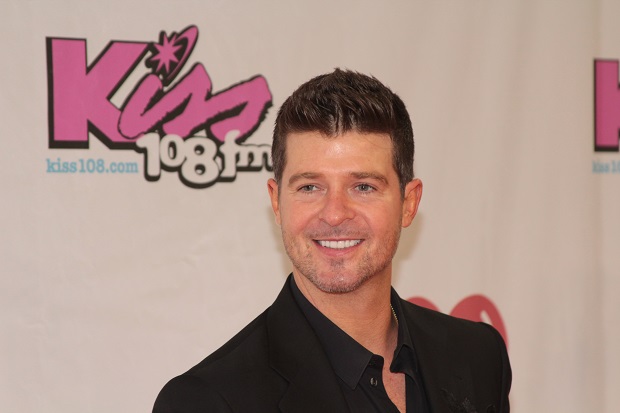

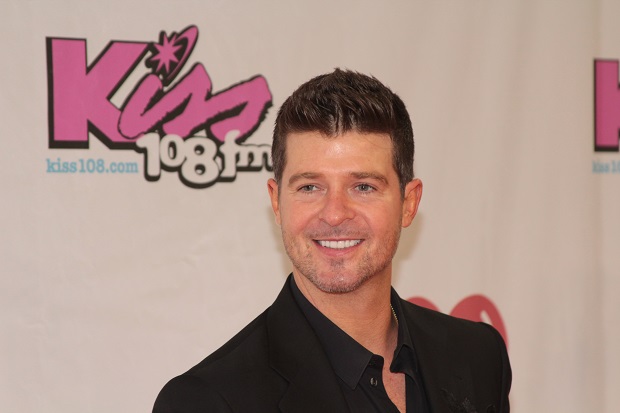

Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines song has been banned in at least 20 student unions after it was released in March 2013. (Image: George Weinstein/Demotix)

I consider myself to be privileged to have the job that I have-I am a university lecturer who teaches Popular Music Culture to undergraduates and post-graduates. This is a subject that is popular among students because the majority of them like music and have an opinion on it. What I love most about my job is the range of interesting conversations my students and I have around popular music and its impact on culture, politics and society.

Music is ubiquitous and it touches people of all cultures, classes and creeds in a multitude of ways. What comes out of the discussions I have highlights both the joy and the anger it can evoke. Some of those discussions can bring forward some sensitive, awkward and challenging opinions and issues but what they do succeed in doing is highlighting issues that we as adults can explore, discuss, argue, rationalise and at time agree to differ on-but in a mature and accepting way, appreciating that we are all different.

So during my lecture on popular music and gender back in November 2013 I opened up a discussion around Robin Thicke’s summer release “Blurred Lines”. I feel no real need to go into any great detail about the fastest selling digital song in history and biggest single hit of 2013. Why? Because the controversy surrounding this song, such as misogynistic positioning with “rapey” lyrics that excuse rape and promote non-consensual sex and, among many other accusations, the promotion of “lad culture”, is abundant on the internet.

My students’ views on this song, and accompanying video mixed with both females and males defending the song and Thicke’s counter argument of it – promoting feminism, it being tongue in cheek and a disposable pop song – to those who, again both male and female, just wanted to castrate him for putting women’s rights and equality back into the dark ages.

Now the scene in the lecture theatre had been set I wanted to garner from them views on what I considered to be equally, if not more important – the issue that over 20 university student unions in the UK had banned the song from being played in their student union bars and union promoted events. This includes the prevention of in-house and visiting DJs playing it on student union premises and ,in some cases, the song not being aired on student union radio and TV stations’ playlists. In their defence the majority of these universities decided to ban after complaints from some of their students, but I am yet to determine whether all these universities reached this decision after an open and democratic process of consensus through voting or otherwise.

What I did find interesting among the many statements from presidents and vice-presidents of the student unions was one given to the New Musical Express, in November 2013, by Kirsty Haigh, the vice president of Edinburgh University Student Association.

The decision to ban ‘Blurred Lines’ from our venues has been taken as it promotes an unhealthy attitude towards sex and consent. EUSA has a policy on zero tolerance towards sexual harassment, a policy to end lad culture on campus and a safe space policy-all of which this song violates”.

However what Haigh does not go on to explain is exactly how this song does that. I am also intrigued by the comment about a policy to end ”lad culture” as Haigh does not allude to a clearly defined set of parameters specifying what counts as ”lad culture/banter”. One might ask if identifying a specific gender (lad) is this not targeting and discriminating against that gender?

I am struggling to find what constitutes ”lad culture” as opinions differ, however the National Union of Students’ That’s What She Said report published in March 2013 defines it as: “a group or ‘pack’ mentality residing in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and ‘banter’ which was often sexist, misogynistic, or homophobic”. But does lad culture equate to sexual harassment-is there a connection or is this creating guilt by association? Some critics claim that ”lad culture” was a postmodern transformation of masculinity, an ironic response to ”girl power” that had developed during the noughties.

Allie Renison’s article Blurred lines: Why can’t women dance provocatively and still be empowered?, published in The Telegraph in July 2013, states that “Teenage girls and grown women spend countless hours confiding in each other about the finer details of physical intimacy, and I can safely say that even without a sex-obsessed pop culture this would still be the case.”

This has to some degree been confirmed by one of my students who is a member of the university girls’ hockey team and girls’ football team. She says that they go out as a group, taking part in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and banter which is often sexist and misandry and involves intimate commentary on the male anatomy and men’s sexual prowess.

So would that then constitute “ladette” culture or “girl power” culture? Do EUSA have a policy to end ladette culture on their campus?

But this isn’t really the core issue here; the issue is around censorship on campus, what constitutes a fair and balanced approach to these issues and where you draw the lines. Thirty years ago student unions were complaining about, and rallying against, censorship-now they are the ones doing the censoring. So where does this leave the issue of censorship?

Starting with music, has Blurred Lines been singled out or do those twenty university student unions have a clear policy on banning songs that might include Prodigy’s Smack My Bitch Up, Jimi Hendrix’s Hey Joe (condoning the shooting of women who cheat on their men), Robert Palmer’s Addicted To Love (the lyrics could be seen to suggest date rape), Rolling Stones’ Under My Thumb, or Britney Spear’s Hit Me Baby One More Time? The list could go on and on, including songs that incite violence, racism or revolution. Do student unions around the country have concise and definitive lists of songs that should be banned or censored or is it a matter for a small group of elected people? And when you leave a group of people to act as moral arbiters then how do you control their decision making power?

Did we not collectively settle this matter in the 90s? Didn’t we conclude that outrage over pop music is a music marketer’s dream and inevitably increases sales for the artist? Aren’t popular music lyrics supposed to be challenging, full of danger and ambiguity? And do we only stop at popular music?

It could be argued that Mozart’s Don Giovanni revels in the actions of a rapist as does Britten’s Rape of Lucretia, and what of literature, do we ban Nabokov’s Lolita, Oscar Wilde’s Salome? Shouldn’t student unions be picketing concert halls, storming the libraries and art collections of universities and start demanding the removal of offensive material or at worst the burning of books and paintings in homage to a misguided Ray Bradbury envisioned cultural pogrom? If you are going to start banning or censoring cultural artefacts then please at least have some sort of consistency otherwise you leave yourself open to criticism.

So is this censorship? I would argue it is. If policy prevents a visiting DJ from playing a particular song at a student union bar, because some people do not approve of it, then that is censorship. I myself do not disagree with the criticism of the lyrical content of Blurred Lines, or condone them, though one could argue about their potential polysemic interpretation. What this highlights is perhaps an inconsistency in the processes of censorship by the student union.

Working in a university, I strongly believe that one of the core purposes of the academy is to create a space to allow young adults, on their journey of personal development, to explore their own opinions and prejudices, while considering those of others. A space where they can hear a multitude of views and draw their own conclusions from them; engage in constructive debate, work these issues through. Universities, of all places, should foster a culture of free speech and free expression wherever reasonably expected. Yes, there are always going to be challenges to what is appropriate and acceptable, whatever those challenges are the banning or censoring of material always has to be done within the law. That is how we develop as individuals and a society.

This article was published on February 26, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org