Opposition member pulled from Russian presidential race

The Russian Central Election Committee has refused to register Grigory Yavlinsky — founder of the Yabloko opposition party — as a presidential candidate. Yabloko did not reach the seven per cent minimum in the State Duma elections, but according to electoral law, the party should still have been able to register Yavlinksy as a presidential candidate with two million signatures in support. The committee rejected 25 per cent of the signatures he collected, deeming them to be defective.

Yavlinsky said that according to the committee’s documentation, less than three per cent of signatures were fraudulent, while the other 23 per cent contained “other infringements of paper execution.” The law says the number of defective signatures must not exceed five per cent.

The party denies the allegations, and continue to insist that the majority of signatures were authentic. Many well-respected artists and public figures signed in support of Yavlinsky, including former Soviet Union president Mikhail Gorbachev.

“The committee’s decision is politically motivated,” Yavlinsky told journalists, expressing concern that authorities are compromising voters’ right to choose a candidate. “Clearly this is not a decision celebrating the rule of law and allowing citizens to influence the election process,” he concluded.

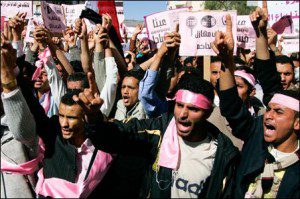

A number of Russian opposition politicians said that refusal to register Yavlinsky could delegitimise the upcoming elections. The organisers of the 4 February “rally for fair elections” condemned the Committee’s decision.

Russian Prime Minister and presidential candidate Vladimir Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told Interfax news agency it is “absurd to protest against the Central Election Committee’s decision.”

Yabloko’s watchdogs are preparing to monitor the presidential elections on 4 March. In December’s Duma elections they reported mass fraud and election law violations, but only a few succeeded in fighting those violations in court. Most judges simply denied allegations and refused to bring law violators to justice. Yabloko activists claim that Russian courts are not independent, leaving the violations unprosecuted.

Russia’s leading independent election monitors’ association, GOLOS, also questions the independence of Russian courts. Deputy director Grigory Melkonyants told Index that election results cannot be disputed in court, as judges refuse to take evidence of violations into consideration.

In the run up to the parliamentary elections, GOLOS was targeted by pro-government media for launching an interactive online map of election violations. The propaganda war against GOLOS is now restarting as they gear up for the presidential elections. After launching a new map of violations, the organisation received a document demanding that they vacate their Moscow offices on 16 January. Police visited a joint event held by GOLOS and Memorial for the first time, and activists from both organisations viewed their presence as an act of “psychological pressure.” A few days before the incident, the head of the Federal Security Service department, in the Komi republic of Russia labeled the organisations as “extremists” aiming to “wreck the upcoming elections.”

With millions angered by Yavlinsky’s removal from the race, and the inability of activists to bring election law violators to justice through biased courts, many believe that the mass protests on 4 February will garner more participants than the last two demonstrations against fraudulent parliamentary elections.