30 Apr 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

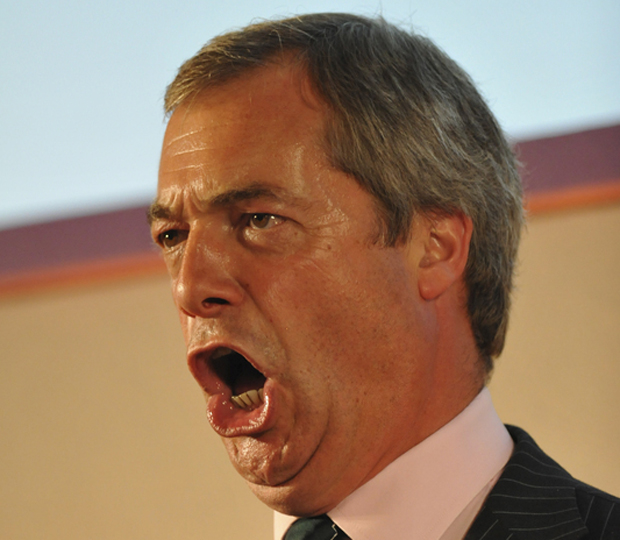

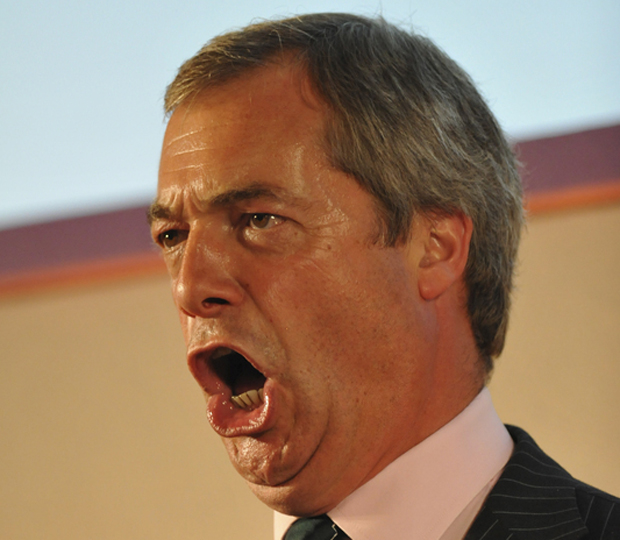

(Photo: Michael Preston / Demotix)

Ofcom’s decision to declare the UK Independence Party a ‘major party’ for the purposes of this month’s European elections has led to questions about who should be allowed to address the public. Behind the scenes, broadcasters have asked why their right to editorial freedom is restricted at all.

UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, responded: “This ruling does not cover the local elections, despite UKIP making a major breakthrough in the county elections last year. This strikes me as wrong.”

Natalie Bennett, leader of the Green Party – which Ofcom decided was not a major party – pointed out that, unlike UKIP, her party has an MP, and is also “part of the fourth-largest group in the European Parliament”.

Both sides pounced on the Liberal Democrats, whose dwindling position in the polls, they hinted, should see it demoted to minor party status.

The decision means commercial TV channels that show party election broadcasts must allow UKIP the same number of broadcasts as the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats. They will also be given equal weight in relevant news and current affairs programming. However, for content focusing on, or broadcasting solely to, Scotland, UKIP’s lower levels of support there mean it will remain a minor player.

This of course gives UKIP a certain level of legitimacy, and the scope to influence even more voters. For those campaigning against them, the move is grossly unfair.

The Green Party in particular feels hard done by. From the House of Lords to local councils it has representatives at every level, but Ofcom still claims it hasn’t achieved enough. Yet in its report the regulator said that it could not make UKIP a major party in Scotland without granting the same status to the Scottish Green Party, due to their comparable performance.

Ofcom has promised to review the list periodically, so things could change in future. But for now it believes the list represents political realities. UKIP’s focus on getting Britain out of Europe has helped it to do well at the past few European elections. In 2009 it came second in terms of vote share, up from third place in 2004, and this year a number of polls indicate that it could win. In more recent local elections UKIP has done well, achieving 19.9 per cent of the total vote in 2013. But this has leapt up from 4.6 per cent in 2009’s local elections, which for Ofcom is not consistent enough to justify extra coverage for its prospective councillors.

So it seems fair enough that UKIP counts as an important party for Britain in the European Parliament. The Greens are yet to win enough votes in enough elections for their inclusion to make sense. And the Liberal Democrats appear to be clinging on only because of their level of support in past general elections, which was also taken into account.

But the real question is why a list is necessary at all. After all a “regulated free press” sounds something like “freedom in moderation” – ultimately a nonsense. Ofcom’s control over which parties receive coverage puts a dampener on broadcasters’ right to freedom of expression and makes it more difficult for newer parties to break through.

Responding to a previous consultation on whether the list of major parties should be reviewed, Channel 4 said the regulator’s rules should “ensure that political messages are conveyed in a democracy… [but] such regulation should be as narrow as possible to restrict… any interference with the broadcaster’s right to editorial independence and its rights to freedom of expression”. Channel 5, meanwhile, said the concept of major parties did not have “continuing relevance at a time of increasing political flux and fragmentation within the electorate”.

Ofcom appears to be prioritising the need of the electorate to be informed. So it could be argued that, for the purposes of allocating party election broadcasts, the list is useful to prevent any channel from steadfastly omitting information on a party that is likely to appear on most voters’ ballot papers.

But in terms of news and current affairs programming, there seems little reason that broadcasters shouldn’t have the freedom to say what they please – particularly because newspapers are faced with no such restrictions.

As the dominance of mass media fades, and the internet provides access to alternative points of view, the restrictions on the news you receive through your TV will only become more obvious.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Apr 2014 | News, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

“Three men walk into a bar.” It’s the set-up for most of the jokes I remember. They’re the kind of jokes that the drunk great-uncle tells at Christmas whilst you titter awkwardly into your fruit cake: often racist, often sexist and always offensive.

Let me tell you a joke.

A girl walks into a bar. She’s tall and blonde, with a privately-funded white smile. My male friend sitting next to me proceeds to ogle her.

“Fit,” he proclaims, “fit as.”

Another male friend laughs. “Don’t even bother going there, mate,” he says, nodding towards the girl. “She’s CU.”

The first friend looks back at the girl and then down at his drink ruefully. “CU,” he says, the two syllables hammer blows in the final nail of the coffin. CU. Two letters, spelling out abrupt endings to chat-up attempts, awkward pauses between strangers during Fresher’s Week; two letters deemed sufficient to define and dismiss a person in a heartbeat. CU: The Christian Union Society. It isn’t a particularly funny punch line.

I’m not a religious person. I think of myself as an agnostic, happily perched on the fence swinging my legs and waving to those either side of me. However, as a chorister in York Minster cathedral from the age of eight to thirteen, I grew up with a healthy respect for religion. Each day I was surrounded by people who had dedicated their lives to God. Although you may question it or disagree with it, it’s hard not to wonder at faith that strong.

Naively, when I arrived at university last September, I believed that other students would also hold a similar view. I imagined students having heated debates- over politics, religion, music, life- before sharing a beer, respecting the each other’s right to an opinion. Instead, university proved a Pandora’s Box of religious stereotypes. Sitting in a friend’s room during Fresher’s, when our conversation turned towards a boy we both knew to be in the CU society, the friend shook her head.

“I don’t understand them,” she said, “They’re all just brainwashed.”

At most universities, there are a number of faith-based societies, ranging from J-Soc (the Jewish Society) and ISoc (the Islamic society) to MethAng (the Methodist and Anglican society). There are certain stigmas and stereotypes attached to all of them, in the exact same way ‘the rugby lad’ has become a typecast. However, it is the CU which seems to be under the most scrutiny by students.

Right from my first week I was aware that being in CU somehow marked you out. Membership rendered you a lesser student, automatically barring you from sex, alcohol and nights out- the ‘key’ components of the university experience. I’m far from the only student aware of these stereotypes. Robin, a student at Canterbury Christ Church, says “Some people might not think they’re ‘cool’ if they join a certain religious group. They may feel alienated from other students.”Georgie, a student at Warwick, agrees. “There is a stigma, but more so about Christians than any other religion. Stereotypical faith member as far as I can tell tends to be female, and really smiley and keen to talk about their religion.”

American teen-culture has done much to establish and enforce this perception. In films like Easy-A and television shows such as Glee, religious- and specifically Christian- High School clubs and cliques are portrayed as self-righteous, its members ‘Bible-bashers’. The focus is often on student celibacy. One scene in Glee shows a meeting of the ‘Celibacy Club’. The club is portrayed as absurd; at the mention of the word ‘contraception’ its president Quinn shouts “Don’t you dare mention the C-word!” The female members are also shown as teases: “Remember the power-motto girls: ‘It’s all about the teasing and not about the pleasing.’” As shown by my friend in the bar, this latter stereotype has been particularly successful in its journey across the pond.

Examining the various stereotypes surrounding CUs, I became curious as to what its members thought of them. Jessie, a first-year CU member at Exeter, says she finds people’s preconceptions hard to cope with. “Telling people you’re a Christian when you come to uni, before people know you, is terrifying ,” she explains, “people do tend to form an opinion about you that you’re a ‘bible basher’ or a ‘goodie goodie’ type person and I know I struggled, and still do struggle with that!” Another anonymous member told me “I think there is definitely some stigma. People are always shocked to learn that some CU people enjoy drinking and going out, for example.”

Some university CUs are actively trying to combat these assumptions. ‘Text A Toastie’ is a popular scheme aimed at getting CU members and non-members in dialogue; students are invited to text a question about Christianity with the promise that a member of CU will arrive at your door with a free toastie and answer to your question. Some students are less than impressed by the scheme. Robin says “I personally think it’s a shame that for some people to feel comfortable speaking about religious issues there has to be food involved.” However, what it does succeed in proving is that Christians are not a clique from a teen-movie, but a group open to discussion and debate. Today university students are lucky enough to have religious freedom and the facilities to express it.

Now we have another goal: freedom from stereotype.

This article was originally published on April 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

24 Apr 2014 | Ireland, News, Politics and Society, Turkey, United Kingdom

Armenian protesters in Lyons accused Turkey of supporting Islamic rebels in an attack on Kessab, an Armenian majority town located in Syria, on the Turkish border. (Image: Benjamin Larderet/Demotix)

It is, as Zhou Enlai might have said, probably too early to tell how significant Tayyip Erdogan’s comments alluding to the Armenian genocide will be.

The Turkish prime minister seems to have broken one of his country’s great taboos. In a statement translated into nine languages, the AK leader said: “It is with this hope and belief that we wish that the Armenians who lost their lives in the context of the early 20th century rest in peace, and we convey our condolences to their grandchildren.”

“Having experienced events which had inhumane consequences — such as relocation — during the First World War, should not prevent Turks and Armenians from establishing compassion and mutually humane attitudes among towards [sic] one another.”

According to Anadolu, Turkey’s state news agency, Erdogan also commented: “In Turkey, expressing different opinions and thoughts freely on the events of 1915 is the requirement of a pluralistic society as well as of a culture of democracy and modernity.”

This is not, you will have noticed, an apology. Offering condolence is not at all the same as expressing remorse. Though some would say it is not Erdogan’s duty to express remorse; he is the prime minister of the modern republic of Turkey, not the Ottoman Empire under which the alleged slaughter of over 1.5 million Armenian Christians in 1915 took place.

And some are utterly contemptuous of Erdogan’s statement: Reuters quotes the Armenian National Committee of America describing the statement as an “escalation” of Turkey’s “denial of truth and obstruction of justice”.

But let us assume that a) Erdogan is in a position to speak for Turkey past as well as present, and b) there is, at the kernel of this, an attempt at reconciliation with Armenia and the Armenian diaspora.

The very mention of the events are significant against the backdrop of the Turkish Penal Code’s controversial Article 301, which forbids insulting “the Turkish nation”. That law has in the past, effectively barred discussion of the genocide, and created a environment where simply identifying as Armenian within Turkey was seen as a provocative act.

The most famous victim of this culture was Hrant Dink, the editor of Agos who was assassinated in January 2007.

Dink saw himself as Turkish-Armenian, and his newspaper was bilingual. He was a firm believer in the potential for dialogue in bringing some reconciliation between Turks and Armenians. He also believed such dialogue could only take place in an atmosphere free of censorship, to the extent that he vowed that he would be the first person to break a proposed French law making denial of the Armenian genocide a crime (a cheap political trick aimed at both currying favour with the Armenian community in France and creating a barrier for Turkey’s proposed entry into the EU).

Ultimately, Dink believed that progress could only be made if we were able to talk freely and access historical debate without impediment or fear.

History, like science, is a process rather than a dogma. And like science, one’s interpretations of history can vary based on both the evidence available and the prevailing mood.

For a long time after the creation of the Irish state, for example, the teaching of history in schools was simple. I recall one primary school history text which seemed to consist entirely of tales of the terrible things foreigners had done to the Irish: first the Vikings, then the Normans, and finally the English. The book finished pretty much where the 1919 War of Independence began. The last page featured the words of the national anthem and a picture of the national flag.

Sympathetic portrayals of English people, and British soldiers in particular, were thin on the ground — Frank O’Connor’s tragic short story Guests of the Nation being one of the very few.

Since the late 1990s peace process, both fictional and historical perspectives on Ireland’s relationship with Britain have changed. Some of the novels of Sebastian Barry, for example, attempt to tell stories of people who were neglected and even vilified in nationalist, Catholic, post-independence Ireland. Part of the plot of Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies has a Catholic school history teacher attempting to get his pupils interested in Irish soldiers who fought for Britain in World War I. Meanwhile, a recent book by nationalist historian Tim Pat Coogan, attempting to paint the Irish potato famine as deliberate genocide rather than cruel neglect, was given short shrift, in spite of the fact that this would have been a mainstream view until relatively recently — one must only listen to the sickly sentimental lyrics of rugby anthem The Fields of Athenry, penned in the 1970s, to understand the appeal of that victim status to the Irish imagination. Wrongs were certainly done in Ireland, but the relationship between the two nations was a hell of a lot more complex than the oppressor/oppressed line that was spun for so many years.

There was no official sanction on differing views of Anglo-Irish relations, but politics permeated the debate. Likewise with the recent intervention of British education secretary Michael Gove on the issue of how World War I is taught in schools. Gove claimed that the idea of a pointless war in which a moribund (figuratively) ruling class led moribund (literally) working class boys to their graves was a modern lefty invention. He was wrong, in that that view had been common even in the 1920s, but his opponents were equally adamant in their insistence that there could only be one view of World War I. None of this discussion was accompanied by new evidence on either side.

At the extreme end of this hyper-politicisation of history are the Holocaust denial laws of many European countries, and laws on glorification of the Soviet era in former Eastern bloc.

In his cult memoir Fuhrer-Ex, East German former neo-nazi Ingo Hasslebach described how, growing up in the DDR, with its overwhelming anti-fascist narrative, nazi posturing was the ultimate rebellion. In the modern era, France’s prohibition on nazi revisionism has led some young north African immigrants, alienated from the French nation state, to see anti-semitism and the quasi-nazi quenelle gesture as the ultimate “fuck you” to the authorities.

Taboos about discussing events of the past breed bad history and bad politics. For the sake of Turkey, and the rest of us, Erdogan should be held to his words on the necessity of free speaking and free thinking.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

17 Apr 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom

(Shutterstock)

James Brokenshire was giving an interview to the Financial Times last month about his role in the government’s online counter-extremism programme. Ministers are trying to figure out how to block content that’s illegal in the UK but hosted overseas. For a while the interview stayed on course. There was “more work to do” negotiating with internet service providers (ISPs), he said. And then, quite suddenly, he let the cat out the bag. The internet firms would have to deal with “material that may not be illegal but certainly is unsavoury”, he said.

And there it was. The sneaking suspicion of free thinkers was confirmed. The government was no longer restricting itself to censoring web content which was illegal. It was going to start censoring content which it simply didn’t like.

If you call the Home Office they will not tell you what Brokenshire meant. Does it mean “unsavoury” material will be forced onto ISP’s filtering software? They won’t say. Very probably they do not know.

There is a lack of understanding at the Home Office of what they are trying to achieve, of how one might do so, and, more fundamentally, of whether one should be trying at all.

This confusion – more of a catastrophe of muddled thinking than a conspiracy – is concealed behind a double-locked system preventing any information getting out about the censorship programme.

It is a mixture of intellectual inadequacy, populist hysteria, technological ignorance and plain old state secrets. And it could become a significant threat to free speech online.

The Home Office’s current over-excitement stems from its victory over the ISPs last year.

Ministers, from New Labour onward, have always tried to bully ISPs with legislation if they refuse to sign up to ‘voluntary agreements’. It rarely worked.

But David Cameron positioned himself differently, by starting up an anti-porn crusade. It was an extremely effective manouvre. ISPs now suddenly faced the prospect of being made to look like apologists for the sexualisation of childhood.

Or at least, that’s how it was sold. By the time Cameron had done a couple of breakfast shows, the precise subject of discussion was becoming difficult to establish. Was this about child abuse content? Or rape porn? Or ‘normal’ porn? It was increasingly hard to tell.

His technological understanding was little better. Experts warned that the filtering software was simply not at the level needed for it fulfill politicians’ requirements.

It’s an old problem, which goes back to the early days of computing: how do you get a machine to think like a person? A human can tell the difference between images of child abuse and the website of child support group Childline. But it has proved impossible, thus far, to teach a machine about context. To filters, they are identical.

MPs like filtering software because it seems like a simple solution to a complex problem. It is simple. So simple it does not exist. Once the filters went live at the start of the year, an entirely predictable series of disasters took place.

The filters went well beyond what Cameron had been talking about. Suddenly, sexual health sites had been blocked, as had domestic violence support sites, gay and lesbian sites, eating disorder sites, alcohol and smoking sites, ‘web forums’ and, most baffling of all, ‘esoteric material’. Childline, Refuge, Stonewall and the Samaritans were blocked, as was the site of Claire Perry, the Tory MP who led the call for the opt-in filtering. The software was unable to distinguish between her description of what children should be protected from and the things themselves.

At the same time, the filtering software was failing to get at the sites it was supposed to be targeting. Under-blocking was at somewhere between 5% and 35%.

Children who were supposed to be protected from pornography were now being denied advice about sexual health. People trying to escape abuse were prevented from accessing websites which could offer support.

And something else curious was happening too: A reactionary view of human sexuality was taking over. Websites which dealt with breast feeding or fine art were being blocked. The male eye was winning: impressing the sense that the only function for the naked female body was sexual.

It was a staggering failure. But Downing Street was pleased with itself, it had won. The ISPs had surrendered. The Washington Post described it as “some of the strictest curbs on pornography in the Western world” – music to Cameron’s ears. Suddenly the terms of the debate started shifting. Dido Harding, the chief executive of TalkTalk, was saying the internet needed a “social and moral framework”.

So instead of proving the death knell for government-mandated internet censorship, the opt-in system became a precursor for a more extensive ambition: banning extremism.

If targeting porn without also blocking sexual health websites was hard, countering terrorism was even more difficult. After all, the line between legitimate political debate and inciting terrorism is blurred and subjective. And that’s not even to address other pieces of problematic legislation, such as the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006, which bans incitement to hatred against religions.

Even trying to block what everyone agrees is extremist content is highly controversial. Anti-extremism group Quilliam and security experts at the Royal United Services Institute have warned that closing websites were people are liable to being radicalised actually hinders intelligence services.

A lot of what we know about Brits going off to fight in Syria or elsewhere comes from the fact they write it on message boards. Blocking them just reduces your ‘intelligence take’. Groups like Quilliam also use those sites to go in and engage with people, offering them a ‘counter-narrative’. Blocking the sites prevents them doing their work.

The Home Office mulled whether to add extremism – and Brokenshire’s “unsavoury content” – to something called the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF) list.

The list was supposed to be a collection of child abuse sites, which were automatically blocked via a system called Cleanfeed. But soon, criminally obscene material was added to it – a famously difficult benchmark to demonstrate in law. Then, in 2011, the Motion Picture Association started court proceedings to add a site indexing downloads of copyrighted material.

There are no safeguards to stop the list being extended to include other types of sites.

This is not an ideal system. For a start, it involves blocking material which has not been found illegal in a court of law. The Crown Prosecution Service is tasked with saying whether a site reaches the criminal threshold. This is like coming to a ruling before the start of a trial. The CPS is not an arbiter of whether something is illegal. It is an arbiter, and not always a very good one, of whether there is a realistic chance of conviction.

As the IWF admits on its website, it is looking for potentially criminal activity – content can only be confirmed to be criminal by a court of law. This is the hinterland of legality, the grey area where momentum and secrecy count for more than a judge’s ruling.

There may have been court supervision in putting in place the blocking process itself but it is not present for individual cases. Record companies are requesting sites be taken down and it is happening. The sites are only being notified afterwards, are only able to make representations afterwards. The tradional course of justice has been turned on its head.

The possibilities for mission creep are extensive. In 2008, the IWF’s director of communications claimed the organisation is opposed to censorship of legal content, but just days earlier it had blacklisting a Wikipedia article covering the Scorpions’ 1976 album Virgin Killer and an image of its original LP cover art.

Sources close to the ISPs say they were asked to take the IWF list wholesale – including pages banned due to extremism – and block them for all their customers, whether they had signed into the filtering option or not.

They’ve proved commendably reluctant, although their reticence is as much about legal challenges as a principled stance on free speech. Regardless, they seem to be insisting that universal blocking can only be carried out with a court order. Brokenshire is then left trying to get them to include it in their optional, opt-in filter.

We don’t know if he’s succeeded in that. The Home Office are resistant to giving out any information. They direct inquiries to the Department of Culture, Media and Sport or ISPs themselves, who really have no idea what’s going on. They refuse to answer any questions on Cleanfeed, saying it is a privately owned service – a fact which is technically true and entirely misleading.

It is not conspiracy. It is plain old cock up, combined with an inadequate understanding of the proper limit of their powers.

The left hand does not know what the right hand is doing. Even inside departments of the Home Office they do not know what they are trying to achieve.

The policy formation is weak and closed. The industry is not in the loop. Media inquiries are being dismissed. The technological understanding is startlingly naive.

The prospect of a clamp down on dissent is real. It would come slowly, incrementally – a cack-handed government response to technological change it does not understand.

We must be grateful for James Brokenshire. His slip ups are the best source of information we have.

This article was originally posted on 17 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org