26 Oct 2010 | Uncategorized

This article appears in Media Guardian

The gathered clan laughed nervously when Lord Saatchi, their host, declared that Britons now spent more on Sky TV subscriptions than they did on bread. When the other man on the stage smiled, the audience relaxed. To understand Rupert Murdoch‘s grip on British public life it is instructive to see the body language when the elite comes together. I counted at least five Conservative cabinet ministers among the great and good in the ornate surroundings of Lancaster House for the inaugural Margaret Thatcher lecture on Thursday.

The timing was equally pertinent. Murdoch’s speech, entitled Free Markets and Free Minds, came the day after the Comprehensive Spending Review that sought not just to tackle the budget deficit but to complete Thatcher’s unfinished business of reducing the size of the state and unleashing the private sector.

Concerns over Thatcher’s health could not mask a celebratory mood among News Corporation executives who, in just a matter of days, have seen the BBC’s budget cut by 16% and Ofcom denuded of staff.

Murdoch, even now, continues to portray himself as the rebel with a cause. “I am something of a parvenu,” he said. At each step of the way, he had taken on vested interests – whether trade unions at Wapping or other “institutions hungry for power at the expense of ordinary citizens”. He argued that technological change was leading to a new “democracy … from the bottom up”. A free society, he said, “required an independent press: turbulent, inquiring, bustling and free. That’s why our journalism is hard-driving and questioning of authority. And so are our journalists.”

Such a laudable commitment to free expression sits uneasily with his company’s dealings in countries with dubious civil liberties records, notably China, where his business interests invariably trump journalistic inquiry.

Murdoch suggested that traditional mediated journalism remained the only serious constraint on elites. “It would certainly serve the interests of the powerful if professional journalists were muted – or replaced as navigators in our society by bloggers and bloviators.” Bloggers could play a “social” role but this had little to do with uncovering facts. In saying this, Murdoch was doing more than justifying the Times’ and Sunday Times’ internet paywall. He appeared to be echoing the views of the New Yorker columnist Malcolm Gladwell, and others who argue that social media and blogs are not speaking truth to power in the way their advocates proclaim.

When tackling the most controversial areas, Murdoch moved from unequivocal statement to hints. The words “Andy” and “Coulson” came immediately to mind when he stated: “Often I have cause to celebrate editorial endeavour. Occasionally I have cause for regret. Let me be clear: we will vigorously pursue the truth – and we will not tolerate wrongdoing.” One News Corp executive suggested afterwards that this was the closest Murdoch had come, and would come, to apologising for the phone-hacking affair.

The official line is that no senior figure knew about the practice at the News of the World. Coulson, who is now director of communications in Downing Street, resigned as the editor when the paper’s former royal editor, Clive Goodman, was jailed in January 2007. Intriguingly, a senior Murdoch executive told me after the speech: “If Coulson hadn’t quit, he would have been fired”. If that is the case, why do they continue to insist publicly that Coulson had done nothing wrong and had fallen on his sword only to protect the reputation of the company?

The other unspoken drama in the room was Murdoch’s bid to take full control of BSkyB and the campaign of resistance by an alliance of newspaper editors and the BBC, who are urging Vince Cable to block the deal.

Murdoch said the energy of the iconoclastic and unconventional should not be curbed, adding: “When the upstart is too successful, somehow the old interests surface, and restrictions on growth are proposed or imposed. That’s an issue for my company.”

The assembled ministers will have taken note. Just as the Labour government kowtowed at every turn, so the coalition – and Cable in particular – will be scrutinised closely by News Corp to ensure that it does the decent thing.

25 Oct 2010 | Middle East and North Africa, News and features

By harnessing the internet to expose the hidden mechanics of war, WikiLeaks puts governments on notice — obsessive secrecy cannot be sustained. Emily Butselaar reports

The most interesting element of WikiLeak’s publication of almost 400,000 leaked secret Iraq war files has been the lack of criticism. This time, military claims that the leaks threaten security and will put the lives of coalition troops in Afghanistan and Iraq in danger have been widely ignored.

There is clearly a public interest in the conduct of wars by our armies and governments and the files reveal that the US did — despite earlier denials — record civilian casualties. They also confirmed the existence of the now infamous Frago 242, the 2004 US army order that directed coalition troops not to investigate allegations of abuse unless US forces were involved. Some of the documents detail thousands of incidents of often stomach-turning torture, abuse and molestation. And others demonstrate governments’ excessive reliance on secrecy.

The anodyne nature of many of the documents demonstrates the over-classification of sensitive material. Secrecy rather than transparency is the norm — national security the justification even where that argument has no validity. If governments are to seek some secrets, they must cultivate a greater culture of transparency as the convention. The US Department of Defence has admitted that July’s unauthorised release of the so called war logs — 91,731 classified US military records from the war in Afghanistan — has not resulted in the disclosure of sensitive intelligence sources.

Julian Assange, Wikileaks’ founder and spokesman, and his band of hacker activists set up the whistleblower site in 2006. With its simple “keep the bastards honest” ethos, Wikileaks was carefully designed to be an “uncensorable system for untraceable mass leaking”. It aimed to discourage unethical behaviour by airing governments’ and corporations’ dirty laundry in public, putting their secrets out there in the public realm.

But with its success — and its many exposés — has come criticism. Earlier this year it released a shocking video of a 2007 US attack in Iraq. Alongside the unedited footage it released an edited 17-minute version that critics claimed was misleading. The release and the title they gave it, “Collateral Murder”, marked WikiLeaks’ move from reporting to advocacy: it was actively protesting the war in Afghanistan.

Handwringing began over the site’s move from objectivity. No longer would it be just a repository of raw source documents. Assange expressed surprise that the site had ever been cast as a bastion of impartiality, describing the concept as idiocy. But a politically active stance made it easier for outsiders to attack the site’s integrity. It could no longer be seen as an objective, neutral spokesman, a change of image that may have long-term ramifications.

The site was also damaged by failures in WikiLeaks “harm minimisation” system, the system by which they redact information. When Reporters Without Borders accused Julian Assange of “incredible irresponsibility” after the release of the Afghan War logs, he cited a lack of resources, an argument it is difficult to find sympathy with when the safety of individuals is involved.

For an organisation on a mission for total transparency the organisation is notoriously secretive about its own activity. It maintains its cloak and dagger antics are necessary to protect its sources, but the very questions that WikiLeaks was set up to address, power without accountability or transparency, can be applied to its own operations.

Today’s Independent focuses on internal rows that have been long-rumoured within WikiLeaks amidst claims that the focus on the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan has subsumed the rest of the organisation’s activities.

It’s easy to forget just how many stories WikiLeaks has broken. Its tremendous success has meant the site has often struggled under the volume of users. It has faced down corrupt governments, investment banks and the famously litigious Church of Scientology, made public top-secret internet censorship lists and broken injunctions — as in the case of the press gag granted to UK solicitors Carter Ruck in the interests of their client, Trafigura.

It’s possible the site will eventually force governments world wide to re-examine concepts of privacy, transparency and secrecy. WikiLeaks is just the vehicle, in the internet age leaks will continue. All governments can do is strive towards a greater culture of transparency if they want to keep their legitimate secrets under wraps.

Emily Butselaar is online editor of Index on Censorship

25 Oct 2010 | Index Index, minipost

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Britain’s privacy watchdog, has reopened its investigation into Google Street View after the company admitted it copied personal data. Google is facing similar pressures from privacy watchdogs in other countries, including Spain, Germany, and Canada. In May, the ICO had investigated revelations that Google had gathered unprotected information but it concluded that no “significant” personal details had been collected. The renewed scrutiny stems from Google’s admission, following analysis by other privacy bodies, that they had harvested more information than previously thought.

23 Oct 2010 | Middle East and North Africa, News and features

“For the preservation of your newspaper and the health of its managing directors, pay careful attention to the following…” Replica front pages inspire a fake directive from the regime. Negar Esfandiary reports

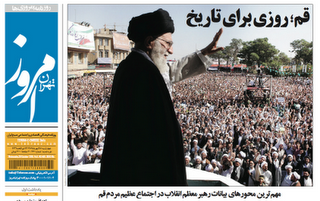

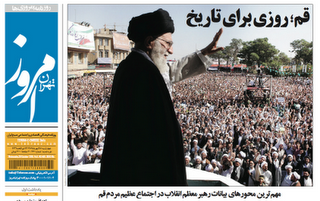

On Friday, browsing an Iranian website 30 mail, I couldn’t help but notice a repeated image of Ayatollah Khamenei standing before a mammoth crowd. At first I thought it was a online freeze but at a second glance the familiar titles of Iran’s newspapers became apparent. Each was faithfully reporting the Supreme Leader’s trip to Qom, the holy city southwest of Tehran. One front page was barely distinguishable from another.

The website Neda Sabz Azadi took advantage of this comic-tragic state of affairs. Under the headline “Bring a logo, take a newspaper” they spoofed a directive from the “Ministry of Culture’s Press Deputy”.

This timely joke coincided with the day that Reporters Without Borders published its annual Press Freedom Index. Iran classified rock bottom at number 175 of 178 countries.

With the identikit front pages there for all to see, the truth was probably not so far from this five point “leaked” missive. Fiction based on fact from a media well-versed in the language of an authoritarian state. Translation of the “directive” below.

On the occasion of the extremely important trip of our leader — but pertinent to all Muslims in human history — to the holy city of Qom the most important city in the world, photographs and suggested headlines are attached.

For the preservation of the status of your newspaper and the health of its managing directors, pay careful attention to the following points:

1. One photo for half front page usage with at least 75 per cent coverage and up to 150 per cent. Note: Newspapers who have received warnings should make every effort to show their goodwill by printing the photograph at 90 per cent. Other more insider newspapers know what to do.

2.The use of at least one of the headlines below is obligatory:

* Vaccination by ‘88 intrigue (insider papers to all use this)

[Implying that the people were immunised and united after the 2009 post-election uprising.

* Ghadir-e-Ghom (only for use by the most insider papers)

[Alluding to a place of pilgrimage (of the same name) in Saudi Arabia where the prophet Mohammad spoke.]