Technology has revolutionised reporting on North Korea. David McNeill reveals how a clandestine network is getting the word out despite restrictions

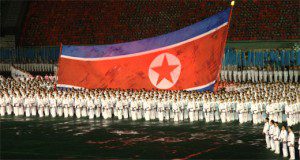

North Korea remains one of the world’s black holes: a vast sealed experiment in information control. According to Reporters Without Borders, just four per cent of the population has access to the country”s heavily censored internet, which is entirely under state control, along with all newspapers, radio and television. Visitors must surrender cell phones and mobile transmitters at the border.

On a visit last September with a group of undercover journalists, we could only send short emails from the five-star Yanggakdo hotel by giving the recipient’s address to a clerk, who typed it into a computer (and charged a euro per line of message). “What the North Koreans have access to is an intranet — it looks and feels like the internet, there are websites, but it’s totally cut off from the rest of the world,” explains Martyn Williams, a reporter for IDG News Service who runs the northkoreatech.org blog. “It”s not connected to anything beyond the borders.”

Naturally, that makes verifying the scant information that trickles out a vexing matter. “You could write a book — or at least a doctoral dissertation — on the lies that have been written about North Korea,” says Richard Lloyd Parry, Asia correspondent for The Times. For years, says Lloyd Parry, it was assumed that Kim Jong-il was mentally ill, an alcoholic, a sex maniac or a psychopath. “Then during the Inter-Korea forum in 2000, there he was on television, obviously fond of a drink but making sense and in control of the situation.”

Over the years, reporters have used strategy, ingenuity and plain subterfuge to peer through the black propaganda and get a clearer picture of life inside the country. Some enter North Korea with government officials or as tourists. Others draw on interviews with defectors for information, including LA Times correspondent Barbara Demick in her acclaimed book Nothing to Envy. Until recently, employing North Koreans as reporters was considered far-fetched, even revolutionary. But technological developments in the last few years have made that a possibility. Mobile phones, mini-cameras and recording devices are increasingly being smuggled out, and the dissenting voices of North Koreans themselves broadcast back into the country.

The implications are potentially profound, says longtime Pyongyang watcher Bradley K. Martin, author of Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. “A stepped-up campaign of providing accurate news about their own country and the rest of the world to a people who are no longer hermetically sealed off from such news could, over time, threaten the regime’s domestic control.”

That’s certainly the goal of Kim Seong-Min, who once wrote poems eulogising the North’s military until he was accused of spying against the regime and defected. He now runs Free North Korea Radio (FNKR) in Seoul and wants to bring democracy to his former homeland, one person at a time. “The world would be a better place without Kim Jong-il, of course. But the most important thing is not him, it’s the people he rules.” Kim pays ten freelance journalists inside North Korea — including a university professor, a teacher and at least two soldiers — a retainer of about $100 a month to file reports. FNKR provides them with small digital recorders for recording interviews and mobile phones with signals that work across the Chinese border, since Pyongyang’s fledgling mobile-phone system was imported from Egypt (in a joint venture with Pyongyang) and is incompatible with the South Korean network.

Why Chinese phones? Because it’s difficult for the North Koreans to monitor calls, explains Martyn Williams of IDG. “On the domestic network it’s relatively easy for the security services to listen in on calls — the mobile operator allows them to do so — but by using a Chinese network the monitoring would have to be done on Chinese soil, and that is probably politically impossible.” But he adds that the North’s security services may have detection units along the border that try to triangulate the source of cell phone signals and catch people using phones.

The recordings are spirited across the Chinese border and transported back to Seoul via a network of spies. The results detonate on air during the FNKR programme “Voices of the People”, where the raw views of the North’s citizens are broadcast back into their own country, electronically distorted.

Kim Jong-il’s wealth comes from “the sweat and blood of the people”, says one. Another vows to protest government policies.

The aim of the clandestine recordings is simple, says Kim: changing the consciousness of ordinary North Koreans for the day when Kim Jong-il steps down. “When power moved from Kim Il-sung [father of the nation] to Kim Jong-il, it was considered a natural development. But people know far more about the outside world now and they’re more sceptical of the leadership, so anything could happen.”

Another defector, Choi Jin I, runs six reporters and four assistants inside North Korea, and at least three more across the border in China, from his cramped office in Seoul. Over the last three years, the reporters have filmed more than 200 hours of video footage, which is smuggled out on tiny SD memory cards and onto television screens in South Korea, Japan and much of the rest of the world. Stills from the reporting are printed in the bi-monthly magazine Rimjingang, published in Hangul and Japanese. “The thing is, digital media has completely transformed how we gather information,” says Jiro Ishimaru, chief editor of Rimjingang in Japan. “A decade ago if you gave a North Korean a video camera they wouldn”t know what it was. Now, cameras are small and anyone can use them.”

The footage is secretly filmed, copied and even edited inside North Korea, he explains. “People have their own PCs. It’s printer drivers that are banned, to stop distribution.” He says that mobile phones can now be used to send texts and possibly more. “We’re very close to being able to send photos.”

The dangers of such clandestine reporting are obvious: Rimjingang’s journalists live in fear of being discovered. In 2007, many of Free North Korea Radio’s original team of stringers were caught and tried as spies, then sent to labour camps or perhaps executed. “We don”t know what happened to them exactly,” says Kim, adding that their capture “devastated” him.

Web-based publishers and blogs are also helping to inform our picture of life inside the North. NK News, run by Washington-based researcher Tad Farrell, aggregates articles, opinion pieces and travelogues from the the net effect countryside outside the Potemkin Village of Pyongyang. It gets about 500 hits a day and claims to have been the first outlet to break the news that Pyongyang’s famous traffic police girls had been retired.

News website Daily NK publishes translated propaganda and has been sourcing stories from stringers and defectors since 2004, with an undisclosed number of correspondents working along the border with China. It also uses about ten translators (some working voluntarily) to bring the latest developments in Korea, China and Japan.

Curtis Melvin, a doctoral student at George Mason University in the US, works with anonymous collaborators to build up a Google Earth profile of the isolated backwater on. Melvin has identified prison camps, military facilities and mass graves from the famine in the 1990s that killed at least 2 million people. “Its Wikipedia approach to spying shows how Soviet style secrecy is facing a new challenge from the internet”s power to unite a disparate community of busybodies,” concluded the Wall Street Journal.

Daily NK has brought details to the sketchy rumours surrounding Kim Jong-un’s rise, and added much needed colour to the profile of Kim Jong-il’s youngest son and likely heir. Florid official propaganda published on the website last year welcomed him as “the number-one guard of [Kim Jong-il]”, joining his father in wind and rain on his official visits. Kim Senior was quoted as calling his son “a genius of geniuses” in propaganda distributed to party cadres. “There is nobody on the planet who can defeat him in terms of faith, will and courage.” The excessive language is a sign, according to the website, that the country’s citizens are being primed for political change.

Money is a headache for all these outlets. “It’s a major struggle,” admits Ishimaru of Rimjingang, which sells its footage to the big television stations, especially in Japan, where 3 to 4m yen for an exclusive is not uncommon. “Our policy is to maintain strict editorial independence,” he explains. “For the networks, the advantage is that there is little or no risk to them.” NK News runs on a tiny budget of perhaps $1,000 a year, but is searching for more regular support. Daily NK relies on fundraisers, donations and subscriptions, says chief editor Park In Ho, though he is coy about the details.

The spate of new outlets has added detail to what we know about the North, but how reliable are they? One problem, says Lloyd Parry, is that “they all have obvious agendas” — to topple the Kim regime. Daily NK, for example, was reportedly intensely disliked by the liberal Roh Moo Hyun administration, which viewed its anti-Pyongyang line as disruptive to its “Sunshine” policy of slow, incremental détente initiated in the 1990s. (Roh was subsequently replaced by the conservative President Lee Myung Bak, who still rules.) But Lloyd Parry accepts that websites and blogs increasingly supplement the knowledge of reporters working the North Korea beat.

“The science of Pyongyang-ology largely depends on the scouring of official propaganda, and looking at photos,” he notes. “Even if you had time to immerse yourself in all that, it”s difficult to get hold of the material. [The new media means] it”s easier to be a Pyongyang-ologist, to access information that used to be the preserve of a few experts.” He cites the example of a Times reader who recently analysed propaganda photos of Kim Jong-il after his stroke in 2008 and described how they were faked in the newspaper”s comments section.

Much of the money that keeps Free North Korea Radio on air comes from the US State Department — at no cost to editorial independence, insists Kim.

“I”m asked about interference a lot, but it’s not an issue. There has been just one clash. We ran a programme carrying testimony by defectors who spoke of their treatment — being beaten by guards at the Chinese border and so on. One defector said he was going to shoot Kim Jong-il. The Americans told us to delete that programme or they wouldn’t pay.”

NK News shuns reporting on the Chinese military for fear of retaliation. “We know what the People’s Liberation Army does in many cases as far as it relates to North Korea, especially when it involves physical activities, troop movements, contemplations of future policy, etc.,” says Park In Ho by email.

“But we don’t want to endanger our reporters and know that China has the power to arrest them at any time and also regards the military as a state secret of some seriousness.” Could the new media eventually replace print or broadcast television?

Tad Farrell doubts it. “I don’t agree that old media is in decline, because people are essentially using NK News as a portal for old media’s online presence — and, I hope, for our own content from time to time as well.” The strength of online outlets is their ability to stretch the limits of reporting, says Park. “Traditional print media are restricted by pages, and television is restricted by time, but we are restricted by nothing. We can write about anything, in as great a quantity as we want.” But he warns that some webbased sources are dragging down the quality and reputation of web-based media. “While the Daily NK emphasises its opinion as it relates to the facts, some other internet news media don”t always deal only with the facts.”

Ishimaru believes his organisation plays a niche role — for now. “They just don’t have people like us working in the big Japanese television stations. In that sense, we’re unique and very useful to them.”

NK News has perhaps the clearest remit of all. “Before the regime changes, our role is to report the news from inside North Korea. Other media outlets read what we write, and if they ask us for anything, we let them know what they want to know,” explains Park In Ho. When the regime falls, his team plans to expand to report the news and views of ordinary North Koreans. “The South Korean people’s voice is already well represented.” The job, he says, is “making sure the voices of the North Korean people can be heard”.

This article is taken from The Net Effect issue of Index on Censorship magazine, The Net Effect. Click here to subscribe

David McNeill writes for the Independent, the Irish Times and the Chronicle of Higher Education. He teaches a course on the media at Sophia University in Tokyo.