The Glamoured

Brightening brightness, alone on the road, she appears,

Crystalline crystal and sparkle of blue in green eyes,

Sweetness of sweetness in her unembittered young voice

And a high colour dawning behind the pearl of her face.

Ringlets and ringlets, a curl in every tress

Of her fair hair trailing and brushing the dew on the grass;

And a gem from her birthplace far in the high universe

Outglittering glass and gracing the groove of her breasts.

News that was secret she whispered to soothe her aloneness,

News of one due to return and reclaim his true place,

News of the ruin of those who had cast him in darkness,

News that was awesome, too awesome to utter in verse.

My head got lighter and lighter but still I approached her,

Enthralled by her thraldom, helplessly held and bewildered,

Choking and calling Christ’s name: then she fled in a shimmer

To Luachra Fort where only the glamoured can enter.

I hurtled and hurled myself madly following after

Over keshes and marshes and mosses and treacherous moors

And arrived at that stronghold unsure about how I had got there,

That earthwork of earth the orders of magic once reared.

A gang of thick louts were shouting loud insults and jeering

And a curly-haired coven in fits of sniggers and sneers:

Next thing I was taken and cruelly shackled in fetters

As the breasts of the maiden were groped by a thick-witted boor.

I tried then as hard as I could to make her hear truth,

How wrong she was to be linked to that lazarous swine

When the pride of the pure Scottish stock, a prince of the blood,

Was ardent and eager to wed her and make her his bride.

When she heard me, she started to weep, but pride was the cause

Of those tears that came wetting her cheeks and shone in her eyes;

Then she sent me a guard to guide me out of the fortress,

Who’d appeared to me, lone on the road, a brightening brightness.

Calamity, shock, collapse, heartbreak and grief

To think of her sweetnes, her beauty, her mildness, her life

Defiled at the hands of a hornmaster sprung from riff-raff,

And no hope of redress till the lions ride back on the wave.

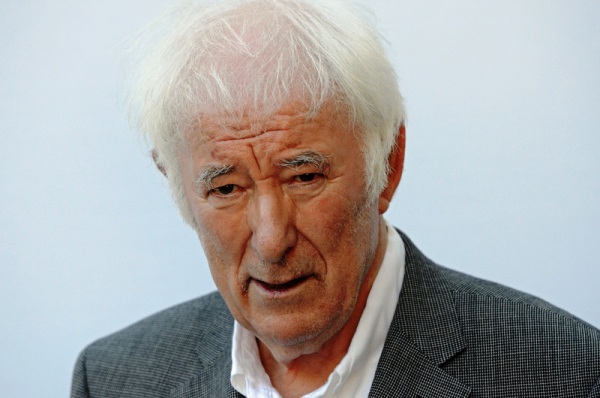

Aodhgan O’Rathaille, translated by Seamus Heaney

The Glamoured is my translation of Gile na Gile (literally Brightness of Brightness), one of the most famous Irish poems of the early eighteenth century. It is a classic example of a genre know as the aisling (pronounced ashling) which was as characteristic of Irish language poetry in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as rhymed satire was in England at the same time.

The aisling was in effect a mixture of samizdat and allegory, a form which mixed political message with passionate vision. After the devastations and repressions brought about by the armies of Oliver Cromwell and King William, the native Irish population became subject to the Penal Laws, a system of legislation as deliberately conceived as apartheid, enacted against them specifically as Catholics by the Irish parliament (representing the ‘Protestant interest’ which took control after William of Orange’s victory over the forces of the Catholic Stuart king, James II, at the Battle of the Boyne). The native Irish aristocracy fled – and were ever afterwards know as The Wild Geese – and dreams of redress got transferred into poetry.

Politically, the aisling kept alive the hope of a Stuart restoration which would renew the fortunes of the native Irish. Symbolically, this was expressed in the ancient form of a dream encounter in which the poet meets a beautiful woman in some lonely place. This woman is at one and the same time an apparition of the spirit of Ireland and a muse figure who entrances him completely. She inevitably displays signs of grief and tells a story of how she is in thrall to some heretical foreign brute, but the poem usually ends with a promise — which history will not fulfil — of liberation in the form of a Stuart prince coming to her relief from beyond the seas.

Aodhgan O’Rathaille (1675-1729) is one of the last great voices of the native Irish tradition, Dantesque in his anger and hauteur, a voice crying in the more or less literal wilderness of the Gaelic outback, at once the master of outrage and the witness of desolation.

Seamus Heaney, Index on Censorship, September 1998