28 Mar 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

“The media tells you what to think!”

That’s a basic criticism of Western journalism, whether it’s of the “CNN controls your mind” or “Left Liberal Elites have monopolised the agenda” variety. Most people reject this, rightly, as a straw-man. We pride ourselves on our ability to sift information, reject weak arguments and come to our own points of view.

A more worrying criticism is that the news directs what you think about. Decisions to give Story X prominence and headlines, and to bury or spike Story Y, mean most of us can only encounter X. Newsworthy stories become obscure if drowned out by others or omitted entirely. We’re denied investigation or campaigning on vital issues because nobody knows they exist.

In Britain this is not what we typically mean by ‘censorship’, not the recourse of despots or prudes. Nevertheless, self-censorship with market and readership in mind denies all but the most devout news-addict important stories. And without the news we can’t have comment pieces, columns, Twitter debates and opinion blogs.

Consider the EuroMaidan protests in Kiev through spring. Coverage gave the impression of a pro-EU crowd led by a heavyweight champion, with a worrying fringe of violent nationalists – Svoboda and Right Sector. This followed the ‘mainstream-extremist’ simplification presented in Egypt, Syria and Libya. Other crucial groups were ignored: LGBT activists set up the protest’s hotlines, feminists ran the makeshift hospitals, Afghan war veterans defended them.

The world’s focus on Kiev and Crimea drove other issues from the spotlight. The Syrian civil war has hardly featured recently, but that conflict has far more casualties, worse upheaval and more immediate consequences for Britain. Refugees are currently en route to claim asylum – this is the last we heard. Similarly, the Philippines dominated the winter’s news after Typhoon Haiyan. Now it’s forgotten in favour of flight MH370 despite the catastrophic ongoing humanitarian crisis, again with more lives at stake.

The Arab Spring is itself a good example of one narrative deafening public consciousness. How many of us knew that at the same time as protests ignited Yemen and Syria in July 2011, Malaysia’s government gassed peaceful crowds and arrested 1,400 protesters after tens of thousands marched for electoral reform? It’s tempting to wonder whether greater coverage, and greater international pressure, could have supported the democratic reforms demanded.

Closer to home, consider the brief uproar caused by the 2013 UK policing bill, drafted to outlaw ‘annoyance and nuisance’ and give police arbitrary powers to ban groups from protest areas. Although the drafts were publicly available, and campaign groups voiced outrage swiftly, left-wing papers took notice only after the bill had passed the Commons. The bill was softened, not by popular pressure or national debate, but by a few conscientious Lords.

Readers could forgive the media for prioritising other stories if they are more pressing. When headlines are crowded by non-events, however, this seems a poor excuse. The British news spectrum was recently obsessed with Labour politicians Harriet Harman and Patricia Hewitt, who worked for the National Council for Civil Liberties (now ‘Liberty’) in the 1970s. That council granted affiliate status to the now-banned Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE). The Daily Mail made a huge splash about its PIE investigation in February, despite uncovering no new information. That paper alone had reported the same story in 1983, 2009, 2012 and 2013. Eventually the BBC, online world and print media all covered the controversy, meaning more worthy issues lost precedence.

Madeleine McCann has dominated countless front pages, reporters chewing over the barest scraps of Portuguese police leaks. No real progress has been made for years. Pundits admit the story retains prominence largely because the McCanns are photogenic, and similar stories would have fallen off the agenda. There are hundreds of similar unsolved child disappearances, just from the UK. Drug scares, MMR vaccine hysteria, celeb gossip and royal gaffes (not to mention Diana conspiracies) complete the non-story roster.

If this seems regrettable but harmless, consider sexual violence. Teacher-child abuse, violent assaults and gang attacks deserve coverage, but their sheer news monopoly perpetuates the public’s false idea of ‘real rape’. Most sexual abuse is between couples or acquaintances: campaigners have shown the myth that ‘real rape’ must involve a violent stranger impedes both prosecution and victim support.

There is no silver bullet, just as no one news organisation can really be blamed for censorship by omission. Few people want or need constant updates on upheaval in South Sudan or Somalia – but we could be reminded they’re happening at all. Editors will always reflect on what is vogue, what will sell, and a diverse free press ensures a broad range of stories. Perhaps the rise of online citizen-reporting can bridge the gap. Nevertheless, the danger of noteworthy events falling into obscurity should niggle at the back of the mind – for those who know enough to think about it.

This article was posted on March 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

28 Mar 2014 | Africa, News, Politics and Society, Uganda

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Ugandans could soon be required by law to love their country. The Patriotism Bill, to be tabled by minister for the presidency Frank Tumwebaze, will require every Ugandan to, among other things, support all government development programs and defend national property. Failure to do so would lead to imprisonment or a fine. The bill would also ensure the establishment of “Patriotism Clubs” in schools to instil patriotic values among pupils and students.

Tumwebaze told the parliamentary presidential affairs committee that if this bill gets enacted into law, it will helping in the fight against a number of societal problems, worst of which is government corruption. “Our constitution demands that Ugandans be patriotic, therefore there is a need for a law to clearly define this obligation,” he said.

However, the move has been labelled a farce by both opposition parties and civil society organisations.

The president of Uganda Peoples’ Congress (UPC) Dr. Olara Otunnu terms it as “utter fraud.” He says that patriotism cannot be a law passed by parliament, but a feeling that comes from inside, appreciating the things that makes you celebrate and be proud your country. “Now unless we say that we should be proud of and celebrate corruption, discrimination, segregation, poverty and brutality, there is no point in being patriotic in Uganda,” Otunnu maintains. He claims the bill is meant to ensure that President Yoweri Museveni is praised across the country.

Renowned Ugandan media personality and social commentator Angelo Izama too disagrees with the idea of compelling Ugandans to love their country. He believes that if the government is indeed serious about patriotism, it should start with respecting the separation of powers among state institutions, and harness the intrinsic values of state symbols to build a stronger national identity.

Others, including Ugandan youth groups, have advised the government that instead of legislating for patriotism, it should create more opportunities for the country’s millions of unemployed young people. Government has in the past years come up with different programs tackling the issue, but these have failed due to corruption among government officials.

Godber Tumushabe, a civil society activist, says that government needs to invest more in social service delivery and overhaul the symbols of state power if it wants Ugandans be proud of, and appreciate their country. While the patriotism debate is raging, the national referral hospital in Mulago recently had its water supply cut off over not paying its water bills, and several children and adult patients recently because the hospital ran out of oxygen. Hundreds of women deliver their babies in the hospital corridors, and tens of mothers and their babies die in childbirth every day.

Prominent Ugandan lawyer and social critic David Mpanga says that government officials call for new laws to hide failure to address real problems, and that existing laws are unenforced due to lack of capacity or poor prioritisation. “How would you measure that love or lack thereof,” he asks.

“Patriotism and the love of a country are important, but they are lacking now for a whole host of social, economic, cultural and political reasons, and not simply because of lack of a law. Parliament can do many things but it cannot make the people love Uganda any more than they do now merely by passing a law,” Mpanga noted.

This article was posted on March 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

28 Mar 2014 | Africa, Gambia, News

Yahya Jammeh (Image: IISD/Earth Negotiations Bulletin/Wikimedia Commons)

Gambia’s president Yahya Jammeh has said he will soon discontinue the use of English as his country’s official language, describing it as “colonial legacy”. The plan appears to be to make a local language the country’s official one, but reports have also emerged suggesting Arabic will replace English.

Speaking at the swearing-in ceremony of the country’s newly appointed Chief Justice, Jammeh — known for his anti-western rhetoric and policies — said for the next “one billion years”, the British have “no moral platform to talk about human rights anywhere in the world”. Gambia gained its independence from the UK 49 year ago, and the president stated that the only British remnant is the English language. “We no longer believe that for you to be a government, you should speak a foreign language; we are going to speak our own language,” he emphasised.

The move comes after Gambia withdrew its membership of the British Commonwealth in October last year, stating that it “will never be a member of any neo-colonial institution and will never be a party to any institution that represents an extension of colonialism”.

The news has been met with opposition. Former diplomat Dr Momodou Lamin Sedat Jobe, now heading the pro-democracy group Gambia Consultative Council (GCC), told news site Jollof that the president’s latest statement is “yet another disappointment”, questioning its feasibility.

“It is much easier said than done,” said Hamat Bah, leader of the oppositional National Reconciliation Party (NRP), in an interview with local newspaper the Point. He said the implications and ramifications would be huge and must be addressed before the change could be made.

Demba Ali Jawo, a journalist and prominent political analyst, suggested that President Jammeh’s announcement was just a diversionary tactic to shift focus from the economic and social problems his government faces. He points out that a change of language would take much more than just mere anti-western rhetoric, arguing that “as our languages are not yet written, we need to develop a dynamic written form which has the capacity to accommodate the rapid technological development, including information technology”. He highlighted the judicial system as a sector where the switch away from English could be particularly complicated, and predicted that it would take much longer than President Jammeh’s own lifetime for Gambia to completely do away with the use of English.

This article was posted on March 28, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Mar 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

There are people out there who claim they can make things go viral. They are lying.

They are the digital version of economists, confidently asserting they can predict the behaviour of millions of barely-rational people, when nothing of the sort is possible. You can maximise the chances of something going viral but you can’t guarantee it, let alone predict it.

In the last few months, I’ve written about a dying man being deported by the Home Office, the decision to secretly restart removals to Somalia and a Home Office document which admits they have no idea whether their drug policy is working. They do fine, but you can often watch stories you spent time working on go out to the usual liberal minded folk, whirl around for a bit and then die a respectable death, with little to no impact on the wider world.

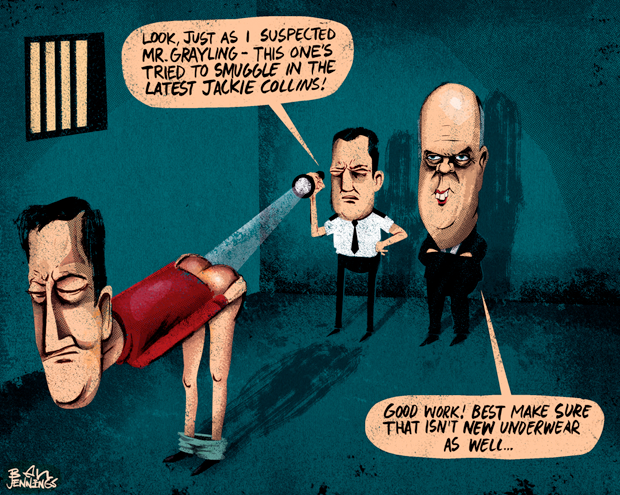

And then occasionally something explodes. A week and a half ago I saw Frances Cook, of the Howard League for Penal Reform, a brilliant but little-understood campaign group, tweeting about justice secretary Chris Grayling’s Incentives and Earned Privileges scheme, which was brought in last November.

It was part of his attempt to look tough on prisoners, the latest chapter in a seemingly endless cycle of tabloid coverage of supposedly cushy prisoner life, followed by a draconian clampdown by the secretary of state and stubbornly high reoffending rates.

Justice secretaries, like all ministers, are far more interested in the views of tabloids than academic researchers. If they valued the latter, they would build small prisons in the local community so inmates kept regular contact with their families, structure internal learning programmes to improve literacy levels and up-skill people so that they don’t rely on crime once they get out. But they don’t listen to researchers. They listen to tabloids, so they end up trying to flex their muscles, which in Grayling’s case is not an agreeable image.

The purpose of the scheme is to make prisoners earn spending money through discipline and participating in their rehabilitation programme. They can then use this (tiny) amount of money to buy things like toothpaste, underwear or, if they want, books.

Core to this project, Grayling says, is the idea that parcels from family and friends must be stopped. The justice secretary has many reasons for this. Perhaps it is to stop gifts making his earned privileges redundant. Perhaps it is because it is impossible to securely scan all the parcels. Perhaps it is because the parcels are sometimes used for contraband. It is hard to tell, because he is prone to using any number of these excuses as he goes.

But regardless of the reason, the Ministry of Justice banned prisoners receiving books or magazines by mail. Books were now considered a reward, not a tool for rehabilitation.

I asked Frances to write politics.co.uk a blog post on it, with a focus on the restrictions on books. But I was in no particular rush. I figured it would be one of those worthy pieces we publish, which get a bit of an airing and some decent traffic for a couple of days, then respectably fade away. I didn’t bother writing a news story about it, given the policy was actually four months old. When she asked what the deadline was, I was rather flippant. “Whenever really,” I told her. “It’s not very time sensitive.”

I published it late on Sunday morning and went off for lunch. The first sign that something had happened came when I went to the loo and checked Twitter (always a dangerous juggling act). Billy Bragg and Caitlin Moran were tweeting it. ‘That’ll get some traffic in,’ I thought.

By the time I went to bed it has been retweeted by the great, the good and everyone in between. A petition had been launched on Change.org.

I talked to Frances on the phone. For someone from her perspective, it is strange when this happens. Groups like the Howards League deal with stories about people being killed in prison and no-one gives a damn. The campaigners and prison officer groups I’ve talked to have been taken aback by the reaction to the piece, and often not a little frustrated. Perhaps people should be more concerned about the fact that inmates are being locked up two-to-a-cell, forcing them to go through the grim humiliation of going to the toilet in front of each other, one told me.

Their problem was mine too: Why do some issues, which might ultimately be more trivial than others, go viral?

In this case it is to do with the almost-mystical power of books in the middle class imagination.

There is a trivial side to this – the bourgeois pretention around books as idol-worship, typified by the stigma around marking your spot by turning the corner of the page. It is a fetishisation of the book, as if Waterstones were one of those Middle Aged tradesmen flogging you a strand of Jesus’ hair. It’s nonsense. Books are nothing but a machine, a tool to get information from brain A to brain B. They are beautiful, but it is a beauty which survives quite well when stuffed into the back pocket of a pair of jeans or covered in coffee stains.

The novel allows access to characters inner life in a way film never can. It is the most empathetic of art forms. Political books, from Paine to Orwell, weigh heavily in the battle of ideas in a way other mediums struggle to match. Even seemingly turgid course text books stand as a tribute to people’s capacity for self-improvement.

These are all vital functions of the book which inmates could benefit from. But for most of them, the importance of books is more sombre and rudimentary. Two-thirds of ex-offenders have the literacy and numeracy levels of an 11-year-old. What they need, more than anything, is young adult literature – appealing, simply written novels which can improve their core reading skills. Perhaps that sounds patronising. It is not meant to be. It is meant to be realistic.

Supporters of the Grayling policy in government told me I was kicking up a fuss so that some mugger could get his hands on a Harry Potter book. I accepted that proposition proudly. It is important that he does. It will do nothing to encourage him mugging someone and might just have a small role in discouraging it.

Anything that stands in the way of a prisoner reading anything is a lunatic act. It costs them more and it costs us more.

This article was posted on March 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org