15 Sep 2014 | European Union, News and features, United Kingdom

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) filed an application on Friday with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg challenging current UK legislation on mass surveillance and its threat to journalism.

Lawyers Gavin Millar QC at Doughty Street Chambers, Conor McCarthy at Monckton Chambers and Rosa Curling at Leigh Day solicitors have been assisting the BIJ with its investigation. The group argues that UK legislation imposes constraints on journalistic free expression and does not offer enough protection for journalists’ sources, therefore it is in breach of Articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

Information uncovered by American whistleblower Edward Snowden appears to highlight how developments in mass surveillance could pose a major threat to the process of journalism. Rules for the interception of data are set out in the Regulation of Investigative Powers Act (RIPA), however, this act does not offer enough controls or checks for external communications. Therefore, any information exchanged through services such as Gmail, Google Docs and Dropbox may not offer the level of confidentiality expected, the group wrote in their application to the ECHR.

It is not only communications which may be scrutinised by the government or secret services; they also have access to metadata, which is the data generated as you use technology. It includes information such as the date and time of phone calls and where emails are sent from. Metadata can be linked to sophisticated computer programs which can enable the user to collate masses of information, building an intricate picture of an individual or organisation’s movements, contacts, sources and lines of enquiry.

According to BIJ, the main implication of unregulated mass surveillance is that journalists can no longer offer anonymity to their sources, or assume that their work is confidential until publication.

This is further compounded by the number of the situations where it is deemed appropriate for surveillance techniques to be enlisted are vaguely defined within the law. It states that data can be intercepted where it is believed that the security or economic interests of the state are involved, meaning investigative journalists especially have to be cautious when covering topics which may be of interest to the government and the intelligence services.

Currently, the BIJ believes the only way in which journalists can be sure they are protected against mass surveillance is to do all of their communications in person, without the use of electronic devices – something which is often impossible, especially if sources are based outside of the UK.

However, under the ECHR journalists should be able to expect protection, the BIJ asserts. At the very least, the group said, this application will spark high-level debate within the government about how journalism and freedom of expression can be protected when governments are using advanced surveillance.

The BIJ says: “In the long term we would like to see proper regulatory control and scrutiny of how the intelligence services use mass surveillance to ensure these techniques and technologies are not being used to hamper legitimate journalistic investigation and inquiry.”

This article was posted on Sept 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Sep 2014 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Russia

(Photo: Okras/Wikimedia Commons)

Pity poor Dmitry Dayneko. The Belarusian teen recently completed the ice-bucket challenge, as millions like him have before, and posted the video of himself being drenched in cold water on social media. So far, so hilarious/tedious (depending on your view of the challenge), but, ultimately, quite harmless.

Except apparently it wasn’t. Dmitry and the friends who poured cold water over his head say they were summoned by local authorities and given a stern warning to behave themselves, apparently on the orders of the KGB in Minsk. The reason? Not the icy water itself, but Dmitry’s temerity in nominating Belarus’ president, Alexander Lukashenko, to do the challenge next.

Lukashenko, one feels, is not a man who does lighthearted fun. One cannot imagine him posting a selfie of himself holding a cocktail with an umbrella in it, hashtagged #YOLO. One cannot even begin to think what he’d wear on fancy dress day at Bestival. He’s probably weirdly competitive at bowling. He does not do Wii.

This does not make him an exceptional dictator. In the history of autocrats, I can’t think of a single one who was mainly in it for the laughs, unless it was fun of the crushing your enemies, seeing them driven before you, and hearing the lamentations of their women variety.

In journalist Ben Judah’s recent, acclaimed essay on the court of Vladimir Putin, he describes a lonesome, rigid emotionless figure, whose only apparent joy is ice hockey, which Judah says, Putin finds “graceful and manly and fun”. This is quite normal for a man of his age and geographical situation (Lukashenko has the same love for ice hockey). But there is a difference between “fun” and “funny”; playing sport is fun. It may even be more fun if your opponents are scared of you. What it is not, though, is funny.

Because dictatorships don’t — can’t — do funny. People can make great jokes about authoritarian regimes, certainly. Ben Lewis’s Hammer And Tickle details the jokes that got people through Soviet communism between 1917 and 1989, most of which revel in the jarring, depressing juxtaposition between Soviet promises of milk and honey and everyday reality (“What is the definition of capitalism?” “The exploitation of man by man” “And what is the definition of communism?” “The exact opposite”.)

But those within the regime, within The Party, never, ever find themselves funny, which is why the generals end up with such large hats.

A couple of years ago, a viral video spread of Belarusian soldiers putting on a display on the country’s Independence Day. It was synchronised, controlled, disciplined, and one the campest things I have ever seen — the Red Army choreographed by Busby Berkeley. But this would not for one moment have occurred to anyone in charge.

Funny doesn’t work for dictatorships because funny usually involves humanity, and vulnerability. This is the appeal of the viral ice bucket challenge video: not admiring the superhuman feat of standing still while freezing water cascades over you, but laughing at the apprehension beforehand, and the hopping and shouting and screaming in the moments afterwards.

In the hands of the likes of Putin or Lukashenko and their apparatchiks, the challenge would have to become a real feat of strength and endurance: somehow Vladimir Putin would invent colder iced water than everyone else did, and then have more of it poured on him than anyone thought possible. And it would be boring because he would not flinch. And then he would not nominate anyone else, because, well, where do you go after Vladimir Putin or Alexander Lukashenko? What man could equal such a task?

Andy Warhol once pointed out that in America, an odd consumer egalitarianism existed: “You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola,” the artist said, “and you know that the president drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking.”

The same is true of viral phenomena like the ice bucket challenge, or the Harlem Shake before it (that meme aggravated the Azerbaijaini authorities so much that people were arrested for allegedly taking part in it). There’s no way of making throwing water over someone’s head much more than it is. The Harlem Shake effectively died when people started trying to make slicker or (shudder) sexier versions.

In spite of near-ubiquitous celebrity participation, an ice bucket challenge is an ice bucket challenge is an ice bucket challenge.

In spite of its claim to oversee a “social state” that works “for the sake of the people”, the Soviet nostalgist regime of Lukashenko cannot bear such egalitarianism.

This article was posted on 11 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

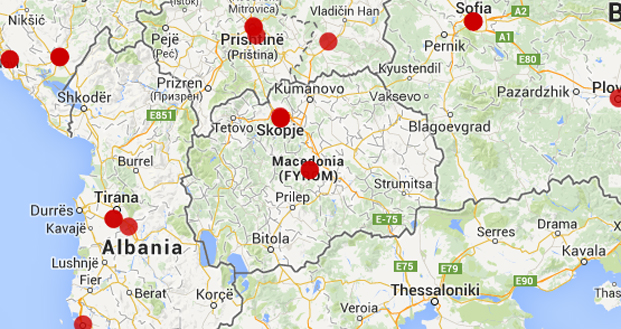

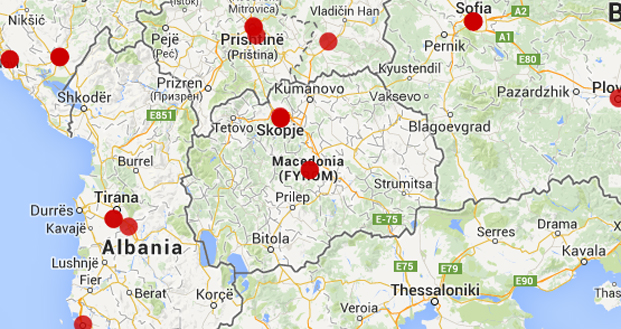

12 Sep 2014 | Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society

Index on Censorship and Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso are joining forces to map the state of media freedom in Europe. With your participation, we are mapping the violations, threats and limitations that European media professionals, bloggers and citizen journalists face everyday. We are also collecting feedback on what would support journalists in such situations. Help protect media freedom and democracy by contributing to this crowd-sourcing effort.

Journalists have raised concerns over a new round of amendments to Macedonia’s Law on Audio and Audiovisual Media Services (LAAMS).

According to the Association of Journalists of Macedonia, the changes increase the role of the director of the Agency for Audio and Audiovisual Media Services in disciplining media. The government can now also subsidise up to 50% of domestic film production costs for private media.

“We find this problematic because it brings risk that the government will influence even more national media by using public funds to cause certain content to be produced and broadcast. In our opinion this should be banned. Obligatory domestic production should be reduced taking into account its financial implication on the media,” Dragan Sekulovski, executive director of the Association told Index on Censorship.

For its part, the agency claims that the law’s aim is to promote media freedom.

“The suspicion for censorship is ill-founded, since, according to the constitution of the Republic of Macedonia, censorship is forbidden,” Maja Damevska, spokesperson for the agency, told Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. “The regulatory body takes care only of proper implementation of the media legislation and therefore has never undertaken a measure or an action that can be considered censorship.”

More reports from Macedonia via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Macedonian Court does not recognise violation of the right to freedom of expression

Macedonian contributor attacked over contribution to Freedom House report

Police officer infringes journalist’s phone data privacy

Telma TV under government pressure

Police pressure journalists during protests in Skopje

This article was posted on Sept 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Sep 2014 | Draw the Line, Youth Board

Free expression and policing can have an antagonistic relationship. Recent events in Ferguson are demonstrative of the issues that arise as the demands for protest clash with those for civil safety.

The police are naturally drawn to the forefront of such a debate as they become the physical manifestation of a state’s commitment to free expression and the right to protest. Thus, as the Obama administration launches a federal investigation into whether the Missouri police systematically violated the civil rights of protesters, it is prescient to ask whether one can demand more of the police to protect free expression.

Undoubtedly, enforcement agencies across the world play a tricky role in facilitating expression while protecting the legitimate safety concerns of the local community. Between 2009 and 2013, police in England spent £10 million on security arrangements for EDL marches. There can also be a huge social cost to galvanic protest and the director of Faith Matters, Fiyaz Mughal, has called for a ban on such marches, claiming that “[We] know there is a corrosive impact on communities, it creates tensions and anti-Muslim prejudice in areas. I think enough is enough. I think a banning order is necessary with the EDL”.

What the recent altercations in Ferguson illustrates is that the role of the police in safeguarding free expression must not be overlooked. More importantly, this is a global issue and as six activists being retried for breaching Egypt’s protest law have started an open-ended sit-in and hunger strike it must be remembered that this debate truly gets to the heart of the basic demands of any civic society.

As scenes from Ferguson have at times resembled the images of police crackdowns in Cairo it is clear that complacency about such issues can prove disastrous. It therefore seems vital to drawn certain lines as to where we feel the police should stand when it comes to creating the basis of a safe but also free society.

This article was posted on 11 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org