6 Jun 2014 | Azerbaijan News, Digital Freedom, News and features

(Image: Bplanet/Shutterstock)

Croatia’s new criminal code has introduced “humiliation” as an offence — and it is already being put to use. Slavica Lukić, a journalist with newspaper Jutarnji list is likely to end up in court for writing that the Dean of the Faculty of Law in Osijek accepted a bribe. As Index reported earlier this week, via its censorship mapping tool mediafreedom.ushahidi.com: “For the court, it is of little importance that the information is correct – it is enough for the principal to state that he felt humbled by the publication of the news.”

These kinds of laws exist across the world, especially under the guise of protecting against insult. The problem, however, is that such laws often exist for the benefit of leaders and politicians. And even when they are more general, they can be very easily manipulated by those in positions of power to shut down and punish criticism. Below are some recent cases where just this has happened.

Tajikistan

On 4 June this year, security forces in Tajikistan detained a 30-year-old man on charges of “insulting” the country’s president. According to local press, he was arrested after posting “slanderous” images and texts on Facebook.

Iran

Eight people were jailed in Iran in May, on charges including blasphemy and insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. They also were variously found guilty of propaganda against the ruling system and spreading lies.

India

Also in May this year, Goa man Devu Chodankar was investigated by police for posting criticism of new Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Facebook. The incident was reported the police someone close to Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), under several different pieces of legislation. One makes it s “a punishable offence to send messages that are offensive, false or created for the purpose of causing annoyance or inconvenience”.

Swaziland

Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu were arrested in March this year, and face charges of “scandalising the judiciary” and “contempt of court”. The charges are based on two articles, written by Maseko and Makhubu and published in the independent magazine the Nation, which strongly criticised Swaziland’s Chief Justice Michael Ramodibedi, levels of corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

Venezuela

In February this year, Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez was arrested on charges of inciting violence in the country’s ongoing anti-government protests. Human Rights Watch Americas Director Jose Miguel Vivanco said at the time that the government of President Nicholas Maduro had made no valid case against Lopez and merely justified his imprisonment through “insults and conspiracy theories.”

Zimbabwe

Student Honest Makasi was in November 2013 charged with insulting President Robert Mugabe. He allegedly called the president “a dog” and accused him of “failing to do what he promised during campaigns” and lying to the people. He appeared in court around the same time the country’s constitutional court criticised continued use of insult laws. And Makasi is not the only one to find himself in this position — since 2010, over 70 Zimbabweans have been charged for “undermining” the authority of the president.

Egypt

In March 2013, Egypt’s public prosecutor, appointed by former President Mohamed Morsi, issued an arrest warrant for famous TV host and comedian Bassem Youssef, among others. The charges included “insulting Islam” and “belittling” the later ousted Morsi. The country’s regime might have changed since this incident, but Egyptian authorities’ chilling effect on free expression remains — Youssef recently announced the end of his wildly popular satire show.

Azerbaijan

A recent defamation law imposes hefty fines and prison sentences for anyone convicted of online slander or insults in Azerbaijan. In August 2013, a court prosecuted a former bank employee who had criticised the bank on Facebook. He was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 1-year public work, with 20% of his monthly salary also withheld.

Malawi

In July 2013, a man was convicted and ordered to pay a fine or face nine month in prison, for calling Malawi’s President Joyce Banda “stupid” and a “failure”. Angry that his request for a new passport was denied by the department of immigration, Japhet Chirwa “blamed the government’s bureaucratic red tape on the ‘stupidity and failure’ of President Banda”. He was arrested shortly after.

Poland

While the penalties were softened somewhat in a 2009 amendment to the criminal code, libel remains a criminal offence in Poland. In September 2012, the creator of Antykomor.pl, a website satirising President Bronisław Komorowski, was “sentenced to 15 months of restricted liberty and 600 hours of community service for defaming the president”.

This article was published on June 6, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Jun 2014 | About Index, News and features

Index calls on MPs to drop clauses 39 and 40 of the new criminal and justice courts bill currently going through the Westminster Parliament. The bill gives the attorney-general the power to require publishers to take down material from their online archives. In order to prevent jurors from accessing content available on the internet, publishers would be issued with a notice ordering them to remove material that is deemed to prejudice criminal proceedings – or face being prosecuted for contempt of court. The bill will go to a third reading in the Commons on 17 June.

Despite the temporary aspect of the removal, we believe that granting the attorney-general – who is the government’s chief law officer – statutory power to order the removal of lawfully published material undermines free speech. It is not clear how such measure would effectively achieve its purpose – preventing jurors from seeking online material related to trials – and it risks airbrushing news stories from history.

In practice, the measure would only apply to media in England and Wales, meaning that if published on international websites, material deemed prejudicial to criminal proceedings will still be accessible to jurors who do not comply with the judge’s instructions. In addition, while the material need only be taken down during trials, appeals or linked trials may mean it is never restored, hence creating potential black holes in the historic record.

We believe that strong juror instructions and education are the way to enforce prohibitions of web research of cases under consideration.

5 Jun 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Poets, we all agree, are terribly misunderstood and undervalued. If it were not for poets, how would we know what things were like other things. How would we live! How would we love! How would we die! They are a priestly class, helping us to mark out our minutes with prayers in pentameter.

But as with any priestly class, they deal in mystery. And demands to decode that mystery are heretical.

This is certainly the impression one would get judging from the reaction to Jeremy Paxman’s comments on poetry and public engagement this week.

Launching the shortlist for the Forward Prizes for poetry, the judging panel of which he chaired, Paxman, with a nod and a wink so heavy that he would have been in serious trouble if the wind changed, suggested that contemporary poetry had “connived in its own irrelevance” by failing to engage with the everyday lives of “ordinary people”. “It’s the general public that poets have to start engaging with,” said Paxman. “And that, I’m, sure, is why the people at Forward said ‘will you join the judging panel’”.

Translation: “The people at Forward knew that me saying something even slightly controversial about poetry would get their prize column inches, and I’m happy to oblige.”

Paxman went on to suggest, whimsically, a public inquisition where poets would explain their work to members of the public, rather than just to other poets.

Frankly, good on Paxman for recognising his use to the Forward Prize. That is not to say he is an man with little to say about poetry; indeed, he’s contributed greatly to the cause of poetry by wheeling out his “Jeremy Paxman” act free of charge for it. He was also, of course, in very careful to praise contemporary poetry and the marvellous books he’d read as a judge.

But that praise was as naught to some poets, who instead chose to pick up on his idea of a people’s panel to judge poetry, and his naughty use of the word “inquisition”.

For people who deal mostly in metaphor, the poets who rose to the bait took the Newsnight presenter’s words remarkably literally.

Todd Swift, a poetry publisher who runs the Eyewear Imprint, wrote that an inquisition was “a strange thing to ask for in an anti-clerical democracy – the idea of burning unrepentant poets at the stake after torturing them is only barely witty in a world where in many many nations, poets really are tortured and silenced.”

Oh Todd. He didn’t mean an actual inquisition.

Swift goes on to say, with an apparent lack of irony that would have horrified the more famous poet of his name: “Only in middle-class (upper class?) London could a white man think interrogating and potentially killing poets was a clever and useful corrective trope. It smacks of easy intellectual arrogance. I find many journalists despise, or fear, or dislike poetry, mainly because poetry is the best-written and most compressed form of language, and is smarter than journalism.”

You tell those journos and their easy intellectual arrogance, Todd!

Swift finishes off by saying “it becomes clear [Paxman] didn’t really read any of the 175 books he was meant to judge”, a statement that is almost certainly defamatory, as any journalist would have told him if he’d asked.

George Szirtes, a poet well respected by his peers, went down a slightly different route. Szirtes, a refugee from the Soviet tanks that rolled over his native Hungary in 1956, compared Paxman’s suggestion to Stalin’s demands for socialist realism from the USSR’s artists.

Szirtes makes some good points writing for the Guardian, but unfortunately they all follow from a sly trick he plays writing that Paxman’s fanciful inquisition would be a place where “poets would be required to explain themselves and, presumably, answer for their failure to be simpler.”

That “presumably” appears to give Szirtes a license to put words in Paxman’s mouth. Suggesting people explain their work is not at all the same as demanding it be simpler, merely that they be capable of (and interested in) talking about their work to non poets.

As another poet, Katy Evans-Bush, put it, writing about the furious condemnations of Paxman on Facebook (Facebook is where poets go to fight; no one is quite sure why). “Heaven forfend that someone from the wider world should look into your ‘cave of making’, see your ‘pellety nest’, and remark on it. ”

This all matters because poetry matters. Poetry is where we learn to play with words, to deal in metaphor, wordplay, the non-literal, the non-prosaic. How often have you heard someone say they’re “not into” or “don’t get” poetry. It’s frustrating, but poets should see that as a challenge, rather than turning in on themselves. That’s not a call to dumb down; it’s a call to act up. When you’re egged on to do so, it’s simply not enough to cry “Stalin!” and retreat further. That’s exactly the hyperbole and self regard that puts people off. If you care about an art form, you should want people to know about it. Otherwise it is youv-vnot Jeremy Paxman or the Forward prize or anyone else – who is censoring poetry.

This article was published on June 5, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Jun 2014 | Azerbaijan News, Events, News and features

(Photo: Kusadasi-Guy via Creative Commons)

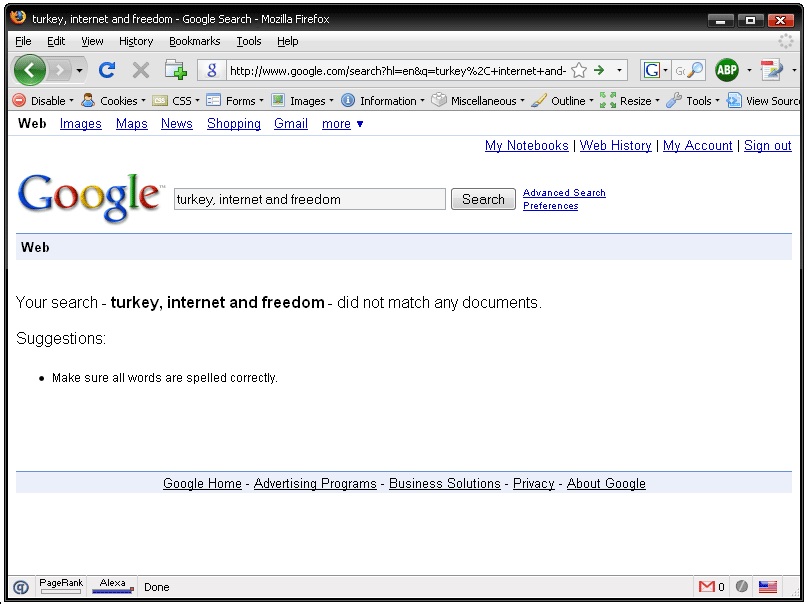

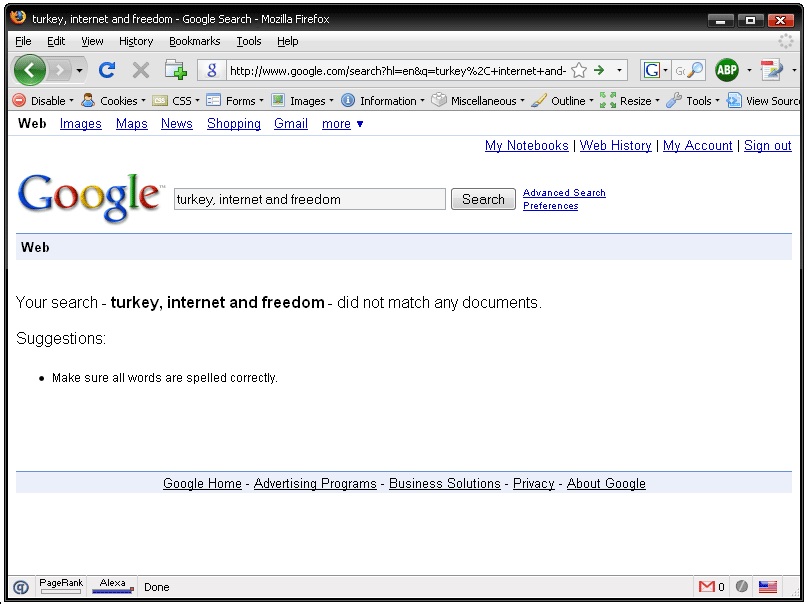

“Whenever we’ll have to choose between excessive regulation and protection of online freedom, we’ll definitely opt for freedom” Vladimir Putin, 1999

Since Putin said this, 3 days before becoming President, history has marched on…

“We will make arrangements without limiting and restricting freedom, but also without bowing to threats and without ignoring the dangers. We will hand over Turkey to generations who are not slaves to technology, but who rule and direct technology” Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, 2014

Terrorised twitter users, blackmailed bloggers and intimidated independent media, digital freedom has been facing a crack-down in Russia, Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Index on Censorship are bringing some of these countries foremost journalists and digital freedom advocates to Brussels to discuss events in their countries, to debate what the EU could do to help and to consider what we ourselves could learn from these experiences?

As we approach several major summits on internet governance, how can the EU tackle the growing risk of fragmentation, avoid calls for forced local hosting and stand up to the top-down approach favoured by the Russians?

“Is it because I was free that I was warned that I was going to lose my column if I would not stop criticizing the government? Is it because I was free that I was fired when I turned a deaf ear to warnings?” Amberin Zaman

The discussion, moderated by new Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg, will include:

- Andrei Soldatov – Investigative Journalist, Founder Agentura.ru. @AndreiSoldatov

- Anton Nossik – Blogger and Founding Editor-In-Chief of leading news websites inc. Gazeta.Ru, Lenta.Ru, Vesti.Ru, NTV.Ru (now NewsRu.com). @dolboed

- Dr Yaman Akdeniz – renowned advocate and Professor of Law, Istanbul Bilgi University, Founder and Director of Cyber-Rights.Org. @cyberrights

- Amberin Zaman – Censored former columnist at Haberturk, current journalist at Taraf and Turkey correspondent for The Economist.

- Arzu Geybulla – Azerbaijani Blogger, based in Istanbul. @arzugeybulla

WHEN: 5pm CET, Thursday 19 June 2014

WHERE: Google, Chaussée d’Etterbeek 180, Bruxelles, Belgium

TICKETS: Free but space limited – RSVP to [email protected]

Follow the discussion live @IndexEvents – #beatingretreat