1 Oct 2015 | Academic Freedom, mobile, News and features, United States

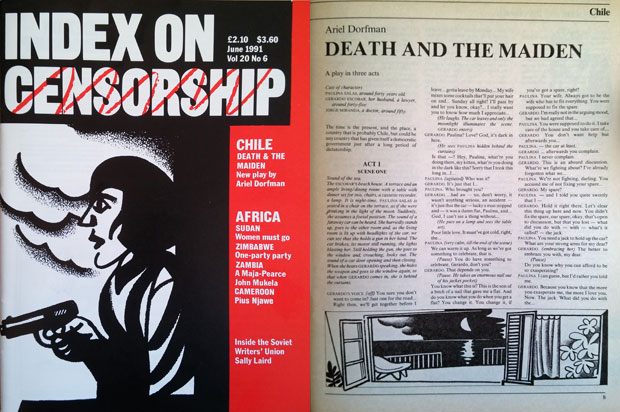

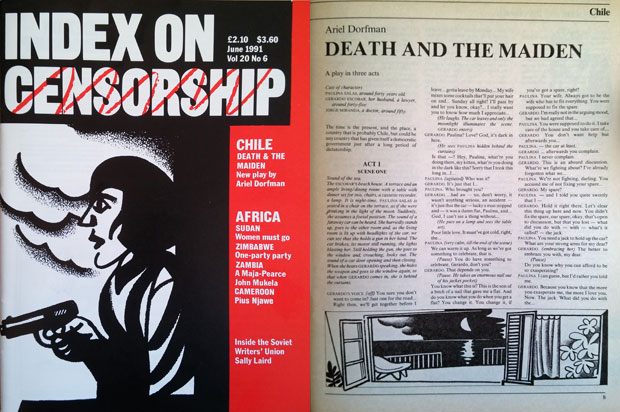

Death and the Maiden, Ariel Dorfman’s play, was first published in English in the June 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Parents and students at a high school in New Jersey have launched a petition to have books, including the play Death and the Maiden by Chilean playwright Ariel Dorfman, removed from mandatory reading lists and be “replaced with material that uses age appropriate language and situations”.

The petition, directed to Rumson Fair Haven high school, has gathered 222 signatures and asks “the administration institute a policy, whereby parents must sign a permission slip if assigned reading material, films or any media contains profanities, explicit sexual passages or vulgar language”. It has prompted a counter-petition, stating that “banning books will only educate students to be more ignorant and dismiss ideas that are ‘not appropriate’ or disagree with one group’s ideas”, which has already overtaken the original petition with 753 signatories.

The calls to remove the book have coincided with Banned Books Week (September 27 – October 3), which celebrates freedom to read and aims to draw attention to censorship of books.

Death and the Maiden was published in English for the first time in the summer 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, and Dorfman’s short story Casting Away was published in the magazine’s September 2014 issue. The writer was forced to leave Chile in 1973 after the coup by General Augusto Pinochet. His life in exile has been very influential in his work as a novelist, playwright, academic and human rights campaigner.

Dorfman told Index: “For someone who has seen his books burnt on television by Chilean military, it is disturbing to witness the attempt in the United States to suppress the views of an author who explores the aftermath of what those military and their allies wrought, the way in which they burnt more than books, the way in which they seared the bodies and the minds of anyone who opposed their overthrow of Chile’s democratically elected government. One of the central issues in my play is the fear and silence that the protagonist, Paulina, has to deal with after she was imprisoned, raped and tortured. To silence the play in which she appears is to be an accomplice of that fear and to spread that fear to those readers and spectators who are trying to understand victimhood and how to survive it, how to heal both individually and as a society. Something that the United States must face, just as Chileans have.”

He added: “The government of General Augusto Pinochet deemed many books, many words, many thoughts, to be ‘inappropriate’. I am saddened by the attempt of some in America to be accomplices, however unwittingly, of that persecution of what they deem profane. And I am encouraged and gladdened to see so many comments to the petitions that stand up for freedom from censorship and the opening of young minds, helping the youth of tomorrow to create a world where the Paulinas – and so many others – will not be subjected to violence because of their beliefs. A world where my wife Angelica and I and our children would not be forced into exile or hear from afar news about the death of our friends in concentration camps.”

Further reading

Free thinking: Reading list for the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015

Judy Blume and her battle against the bans

Student reading lists: Threats to academic freedom

1 Oct 2015 | European Union, mobile, News and features

Dunja Mijatovic is the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media. (Photo: OSCE/Micky Kroell)

Each autumn, more than 1,000 government and civil society representatives from 57 countries of the OSCE get together in Warsaw for a two-week discussion on a wide variety of human rights issues. The purpose of the meeting is to scrutinize each country’s performance on human rights standards they signed up to in areas such as free expression, free media and the panoply of basic rights prevalent in modern, liberal societies. It is designed to be a thoughtful and lively event that gets to the heart of implementing states’ commitments on the issues.

This year the first topic was dedicated to freedom of expression and the keynote speaker, Danish human rights lawyer Jacob Mchangama, raised “the issue du jour”: “Does a genuine commitment to tolerance, equality and nondiscrimination really depend on restricting the very freedom that has made possible the articulation and spread of new and progressive ideas from religious toleration in 17th century Europe, the abolishment of slavery, the equality of the sexes, criticism of apartheid and the rights of LGBT people?”

The issue, of course, is whether we need the spate of new laws enacted worldwide designed to somehow strike a balance between the right of free expression and the desire to weed out intolerance and hate in society.

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January, the answer to Mchangama’s question may well form the superstructure of the rights to free speech in the years to come.

We don’t need new laws. Indeed, it is time we stop looking at unbridled speech as something that promotes intolerance. We should see it as an opportunity to protect the rights of minorities and marginalised people to speak when the powerful are making distressing noises.

My reasoning is based on the simple view that when it comes to media freedom, those who govern least, govern best.

Even the best-intentioned laws cannot prevent intolerant speech. And general notions such as “hate speech” preferably should be avoided because they can be arbitrarily interpreted.

It is a decidedly New Age thought, likely first made popular by the 19th century essayist Henry David Thoreau in his essay on Civil Disobedience.

But today it is commonly thought that laws criminalising hate speech are beneficial to marginalized groups that need state protection. In reality, it is the marginalized groups who need the freedom of speak without fear of prosecution to press their causes and affirm their rights in society.

As Mchangama said in his address: “The freedoms that (sometimes) allow bigots to bait minorities are also the very freedoms that allow Muslims and Jews to practice their faiths freely. By further eroding these freedoms, no one is more than a political majority away from being the target rather than the beneficiary of laws against hatred and offence.”

Indeed, a significant development post-Charlie Hebdo has been the distressing comments by some that openly suggested the magazine’s staff “had it coming to them” for publishing illustrations satirising the prophet Muhammad. Just think of it: the victims of an outrageous act of silencing speech actually became, in some people’s eyes, the guilty ones.

It is time for some civility in the chaotic world of free speech. As I wrote shortly after the attack: “Intolerant speech should be primarily fought with more speech.” I still believe that is the foundation of any attempts to regulate content.

Following that line, I suggested, among other things, that participating states (the member countries of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe):

· Refrain from banning any form of public discussion or critical speech, no matter what it refers to;

· Take all possible measures to fight all forms of pressure, harassment or violence aimed at preventing opinions and ideas from being expressed or disseminated; and

· Eliminate restrictions to freedom of expression on the exclusive grounds of hatred, intolerance or potential offensiveness. Legislation should only focus on speech with can be directly connected to violent actions, harassment or other forms of unacceptable behavior against communities or certain parts of society.

My full statement on this issue.

30 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

|

Battle of Ideas 2015

A weekend of thought-provoking public debate taking place on 17 & 18 October at the Barbican Centre. Join the main debates or satellite events.

5 Oct

Does free expression have its limits?

Join Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley for a Battle of Ideas satellite event to debate the limits of free expression. With Dr Wendy Earle, Anshuman Mondal, Kunle Olulode and Tom Slater.

When: Monday 5th October, 7-8:30pm

Where: Nunnery Gallery, Bow Arts Trust, 181 Bow Rd, London E3 2SJ

Tickets: £4.89 through Eventbrite

• Full details

17 Oct

Artistic expression: where should we draw the line?

Join Manick Govinda, Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg, Cressida Brown, Nadia Latif, Nikola Matisic with chair Claire Fox at the Battle of Ideas festival.

When: 17 October, 4-5:15pm

Where: Cinema 2, Barbican, London

Tickets: Available from the Battle of Ideas

• Full details |

It’s just over a year ago since a mob of anti-racist activists closed down South African theatre director Brett Bailey’s tableaux vivants work Exhibit B in London. The work had actors depicting the horrors of historical slavery, and colonial racism as museum exhibits, echoing the human zoo exhibits of 19th century, which still took place right up until the 1950s.

The work was powerful, visceral, steeped in humanity and stirred a powerful emotional response in the spectator. Yet, it seemed that this physical artistic expression was a step too far for many on the left and Britain’s black community. Most of them, and the 23,000 who signed the petition calling for the Barbican to shut down the work, hadn’t seen the performance. Instead, they felt triggered by a series of publicity photographs of actors performing actions of enslavement and of human bondage.

An image of a semi-naked black woman, sitting, waiting on a bed with her back to the camera, and the reflection of her face and eyes looking back at the viewer, composed and calm was uncomfortable viewing. The living tableau, entitled A Place in the Sun, colonial exhibit, Paris, 1920s was based on a factual account of a French colonial officer who kept a black woman chained to his bed, exchanging food for sexual services. This took place during the French, Belgian and Portuguese scramble for rubber in the Congo. It is a difficult image, the performance brought home the tenderness and active being of the captive woman and stirred emotions of both anger and sadness, as did all the tableaux which took us right to the present day, depicting deported refugee individuals who were killed by the hands hired immigration border security forces. It is hard to disagree with the Brett Bailey’s sincerity that the work is a hard-hitting indictment against racism.

Yet, for the protesters Exhibit B was “an exhibition by a privileged white man who benefited from the oppression of African people in the country [South Africa] in which he grew up, which objectifies black people for a white audience.”

At the opening night in London, 200 angry protesters, with the assistance of the British police force, successfully censored the work. Exhibit B will probably never be performed in England for the foreseeable future.

In the past, artistic, particularly literary works such as DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, James Joyce’s Ulysses to name a few were banned by state officials and enforced by draconian laws such as the Obscene Publications Act 1959. However, recent censorship of artistic expression is no longer the domain of the state and its officials. It is now curbed by radical activists and also by curators and arts professionals who feel too morally weak to defend and stand by controversial works of art. The police are now called in for their advice on artistic expression and inevitably, in the name of ‘public safety’ works of art are censored from the public.

Only recently we witnessed the censorship of a witty series of satirical photographs by an anonymous artist called Mimsy (sorry Banksy, you’ve been up-staged) depicting the popular children models of Sylvanians (cute furry creatures that akin to those in Beatrix Potter’s tales) innocently enjoying leisurely pursuits such as family picnics, sun-bathing on a beach, having a few pints or just simply watching TV where they are threatened by masked, armed creatures in black uniform called MICE-IS “a fundamentalist terror group [threatening] to annihilate every species that does not submit to their hardline version of sharia law”. However, this wasn’t taken down due to any law being contravened. The work, pulled from an exhibition at the Mall Galleries in London entitled Passion for Freedom (oh the irony) was a result of the gallery managers asking advice from the police as they felt uncomfortable with the “potentially inflammatory content of Mimsy’s work”. The police agreed that the work was inflammatory and couldn’t guarantee the safety of the gallery or visitors, therefore £36,000 would have to be paid to the police force for security cover.

Censorship by fear of terror, by mob-rule, by “triggering’ traumatic feelings, the growing self-censorship of artistic works and the British state’s lily-livered position in defending free expression come into arbitrary play, leading to a worrying situation where potentially any work of art can be censored.

It’s easy to morally grandstand and point the finger at the horrific killings of cartoonists and bloggers in Bangladesh and Iran and criticise the Chinese authorities for their ‘house imprisonment’of Ai Weiwei, but if we cannot defend all forms of artistic expression from the high arts to popular culture, we are seriously compromising artistic freedom for fear of upsetting various communities of interests, be they Muslims, feminists or anti-racists.

I am currently reading Azar Nafisi’s brilliant latest book, Republic of Imagination (2014) where she writes a chapter on the US writer Mark Twain’s 1884 novel Huckleberry Finn as a major inspiration in her life and moral outlook. The novel is currently triggering some US literary students and professors into a state of apoplectic trauma as the word ‘nigger’ is used 219 times in the novel. The decision to re-publish the novel and replace the word ‘nigger’ with ‘slave’ is a dangerous re-writing of history and art. Nafisi defends artistic expression unreservedly and quotes from one of Twain’s notebooks as follows:

“Expression – expression is the thing – in art. I do not care what it expresses, and I cannot tell, generally, but expression is what I worship, it is what I glory in, with all my impetuous nature.” (Republic of Imagination, p.88)

Art should be dangerous, unsettling, funny, an emotional journey, beautiful, entertaining and yes, obscene. Artistic expression, in all its manifestations, is a value that must be defended in our Western democracies. We should heed Mark Twain’s wise words.

Manick Govinda is head of artists’ advisory services for ArtsAdmin

Govinda is participating in the 17 Oct Artistic expression: where should we draw the line?Battle of Ideas session with Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg, Cressida Brown, Nadia Latif, Nikola Matisic with chair Claire Fox at the Battle of Ideas festival.

Index on Censorship magazine editor Rachael Jolley is speaking at Does artistic expression have its limits? at the Bow Arts Trust on Monday 05 October