6 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Serbia

Journalists and citizens in Serbia’s northern city of Novi Sad are taking the streets after a wave of dismissals at the regional broadcaster Radio Television Vojvodina, which they believe is a direct result of political pressure.

It was late in the afternoon on 17 May when journalist Vanja Djuric heard that her job was no longer necessary. “We had just prepared the news items for the next day,” she told Index on Censorship. “They just told us, ‘You don’t have to come to work tomorrow.’”

She was not the only one. By the end of that week, 18 RTV employers had been replaced without explanation. Some received a phone call, others were stopped in the building’s hallway. “The whole newsroom, all the editors and journalists, we’d all been sent home,” Djuric added.

Novi Sad, Serbia’s second city, has been the centre of protests for media freedom ever since. Thousands have taken the streets to demonstrate against editorial reforms at one of the biggest public broadcaster in the country. Protesters believe that the ruling party of Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic is gradually taking control over the radio and tv station that used to be one of the few independent broadcasting media companies in Serbia.

It is believed that the dismissals of RTV editorial staff was a direct result of a shift in government in the autonomous province of Vojvodina.

Elections had taken place on 24 April and the results, which caused a dramatic shift in power when the results were revealed on 4 May. The Serbian Progressive Party had won a majority like it already had on a national level.

The national equivalent of RTV, Radio Television Serbia, is already under strict government control, and major concerns have been raised that RTV is now headed into the same direction.

Over 100 journalists and editors have signed an open letter criticising the dismissals and asking the new board of directors to resign and to restore free media at RTV. A newly formed protest movement called Podrzi RTV (Support RTV) has organised four protests so far.

Vojvodina’s journalist association, the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina, believes that the new political leaders were intended to take over the public broadcaster. “The political takeover of one of the most objective televisions in Serbia started immediately after the elections with the non-transparent replacement of RTV’s programme director,” Nedim Sejdinovic, president of the Independent Journalist Association of Vojvodina told Index on Censorship.

“Soon after that the general director and the director of one of the most popular news programmes resigned,” he said. “It was the start of the new leadership.”

Most journalists were taken off their editorial positions and transferred to non-journalistic jobs within RTV. The programme schedule changed overnight. “Under the excuse of ‘summer shifts’, they took down almost every political and investigative programme,” Sejdinovic said.

While the majority of the journalists are still on the payroll, five prominent journalists so far have been fired.

NDNV is expecting more journalists to lose their jobs in the coming months. The association is looking into the dismissals with a team of lawyers. “We found out that most dismissals were against the law so we are preparing court cases up to the European Court for Human Rights,” said Sejdinovic. Serbia’s national journalist associations NUNS and UNS, as well as the OSCE have strongly condemned the developments at RTV.

Journalist Sanja Kljajic was working on RTV’s recently launched investigative journalism programme, which was also cancelled by the new management. She is one of the initiators of the protest movement Podrzi RTV.

“We’ve been accused that we were not objective and didn’t fulfil our role as a public service, with no evidence or arguments,” she told Index on Censorship. Her show was called Behind the Wall, the first season was about to start, dealing with the country’s problems within the judicial system. “Bearing in mind that we were doing research about terrible results of the judicial reforms over the past 15 years in Serbia, we are sure that the reason for cancelling the project is a textbook example of censorship,” said Kljajic.

RTV had a unique reputation in Serbia, where the media has become more and more unfree in the recent years. It had managed to operate objectively and has been praised for being one of the few broadcasters in the country that managed to resist political pressure. While other public media have turned into a mouthpiece for the prime minister, RTV kept broadcasting debates and critical reports. Sanja Kljajic was proud to be a part of it. “I was free to ask any question to anyone,” she said.

That started to change already in the period leading up to the elections. There were signs that control was about to get tightened. At the beginning of April, journalist Svetlana Bozic-Kraincanic was expelled and had her salary cut after asking the prime minister, Aleksandar Vucic, a critical question during a press conference. It was election time, Vucic was running to be re-elected. Bozic-Kraincanic touched on a sensitive topic asking him about his ties with the Serbian Radical Party of the recently acquitted war criminal Vojislav Seselj, a party of which Vucic was a member during the 1990s war in former Yugoslavia.

“It is very disturbing that RTV is now transformed into another media that serves the regime of prime minister Aleksandar Vucic,” said Nedim Sejdinovic of NDNV. However, he also sees optimism in the response it has got. “The protests have brought out to the streets of Novi Sad not just journalists, but also citizens themselves,” he added. “The story of journalists became the story of the people. They are coming to the protest to show their growing dissatisfaction with the current government.”

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the date of the elections.

5 Jul 2016 | Events, What A Liberty!

On Wednesday 6 July, What a Liberty! will launch their Magna Carta 2.0 at the Collection Museum in Lincoln.

Since February, eighteen British teenagers have worked together to re-imagine the Magna Carta and create their own Great Charter, the Magna Carta 2.0. Led by Index on Censorship and funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, Magna Carta 2.0 aims to spark discussion, provoke change and encourage young people to make sure their voice is heard. The group focused on the need for justice, equality, education and environmental consciousness. They have launched a self-managed website and social media presence to spread the word and spark discussions about human rights in the 21st century.

This event is open to the public – and will include a presentation from the group, audience Q&A and speeches from special guests, including Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine. Following the presentation, we’ll be hosting a tea reception at The Collection, a chance to meet the group and other invited guests.

2.15pm-3.15pm – presentation and discussion

3:15pm-4:15pm – tea reception

The Collection Museum, Danes Terrace, Lincoln, LN2 1LP

“We’re here to influence the future. We’re here to promote a new charter. We are Magna Carta 2.0.”

5 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Events

How can we protect a free media and space for civil society? What are the growing restrictions facing journalists? How can investigative journalism fight corruption?

As the space for free media in Europe is threatened, the importance of an independent media must be emphasised. A free and independent media plays a vital role in exposing corruption and holding governments and the corporate world accountable.

Join Transparency International EU for a conference on “The Role of Investigative Journalism and a Free Media in Fighting Corruption” including:

Restrictions on Media and the Press in the European Union, 3.45pm-4.45pm

- Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive, Index on Censorship

- Andras Peltho, founder/editor, Direckt 36 Hungary

- Dirk Voorhoof, board member, European Centre for Press and Media Freedom

Investigating Corruption, 4.45pm-5.45pm

- Miranda Patrucic, editor, Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project

- Kristoff Clerix, Knack Magazine (ICIJ member who has worked on LuxLeaks, SwissLeaks and Panama Papers)

When: 2-6pm, 14 July

Where: Residence Palace, Rue de la Loi 155, Brussels

Tickets: To attend this event, register here. To apply for a travel grant contact [email protected]

5 Jul 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, France, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

In almost four months covering protests against France’s labour reform bill, a number of journalists in the country have faced intimidation, detention and injury. Others have had their equipment broken or been physically prevented from doing their job.

On 9 April, a group of protesters threatened journalists in Rennes. The following month, a journalist working for Le Figaro newspaper was hurt by a projectile, likely to have been thrown by a protester and aimed at the police.

However, there have been more reports of violence against journalists being perpetrated by police forces. On 5 April, a Mediapart journalist reported that a member of the police force tried to break his phone while he was filming a violent arrest at a protest in Paris. On 10 May, a journalist who works for Les Inrockuptibles was hurt by a grenade launched by riot police during a protest in Paris. Six days later, it was alleged that an Agence France Presse journalist had their camera broken by a police officer while filming an arrest.

Journalists have also been attacked with batons and one as hurt by a Flash-Ball gun. On 23 June, two independent journalists, including Gaspard Glanz from Teranis News, were detained for hours in a police van while on their way to cover a protest in Paris.

“I didn’t think this could happen in France,” Julie Lallouet-Geffroy, an administrator for Club de la Presse de Rennes et de Bretagne and journalist for Reporterre, told Index on Censorship.

Club de la Presse de Rennes et de Bretagne, a press club based in the city of Rennes, Brittany, has been particularly active in denouncing violence against journalists covering the local protests. After journalists were attacked in Rennes on 2 June, the group took the case to France’s constitutional ombudsman for citizens’ rights and met with the interior minister.

Lallouet-Geffroy told Index what happened when journalists were caught in the middle of the clash between police and protesters. “Police forces first hit an independent photographer, then they hit Vincent Feuray [a contributor to Libération],” she said. “He fell to the ground unconscious and remained unconscious for a few seconds.”

Lallouet-Geffroy said she was also shoved by police.

She told Index that meetings with journalists at the club resemble “group psychotherapy”: “Journalists often won’t talk about this type of incidents – they consider it’s just behind-the-scenes stuff. But soon you realise that journalists working for very established media outlets, such as AFP or France 3, who have a 12kg camera on the shoulder, are teargassed at point-blank range. What really struck me is the banalisation of such violence.”

Reporterre recently published a report on police violence against protesters, which includes a few pages on cases where journalists were targeted. “What’s disconcerting is this litany of violence in all French cities, with the same words and the same incidents reappearing while police forces are supposed to protect citizens,” said Lallouet-Geffroy.

The emergence of new journalists and new media outlets that occupy a grey zone between journalism and activism has been seen as disconcerting for some.

“There are young journalists who will go on the hotspots, taking risks that journalists who have a steady job won’t take,” Lallouet-Geffroy said. “Sometimes it feels like they are cannon fodder, particularly isolated, with no outlet to have their back if they get in trouble or if they are sued for libel. Some of the images they get are really valuable, though.”

Teranis News recently published an “encyclopaedia of police violence”, to show force being used against protesters.

The deteriorating relationships between French police and young people continues to be a problem. It was announced on 29 June in the National Assembly that a plan to issue written receipts to people stopped by police, which organisations fighting police violence have long campaigned for, would not be implemented. A popular chant among French protesters remains: “Tout le monde déteste la police” (“Everybody hates the police”).

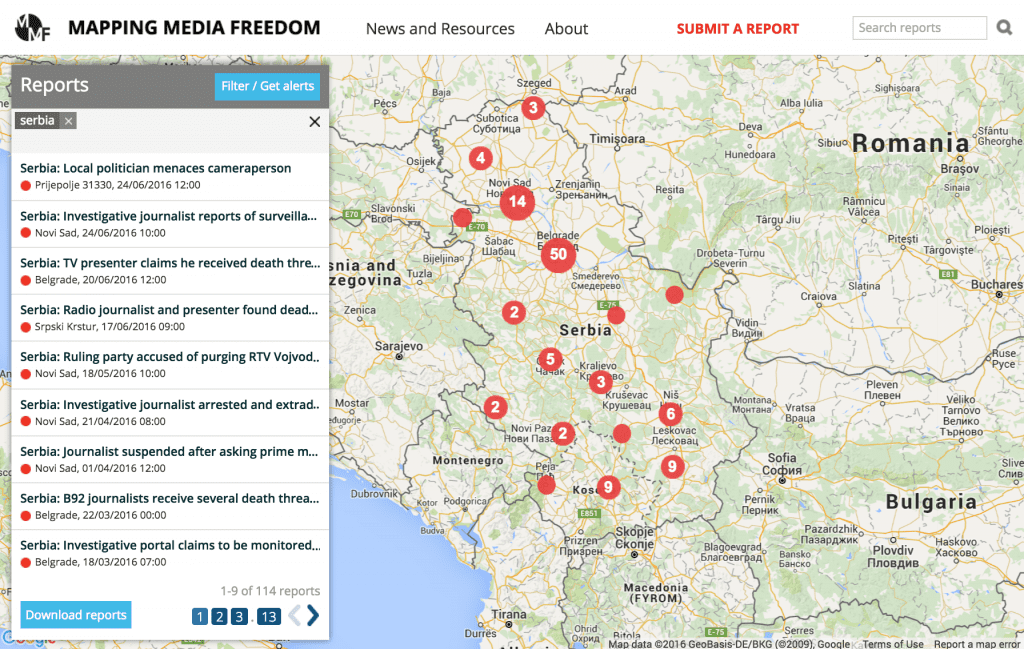

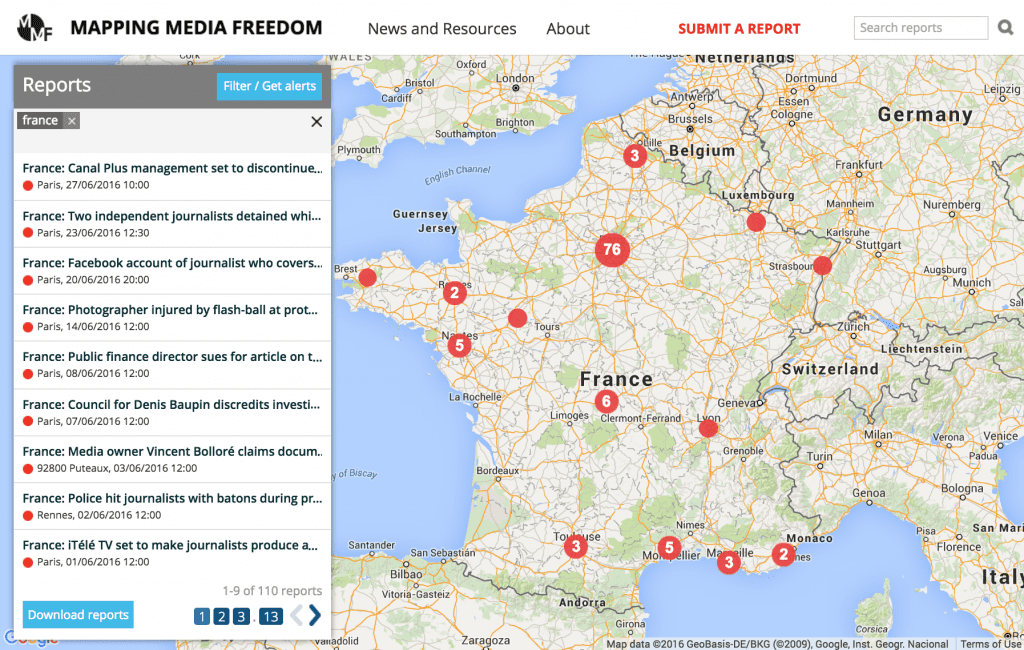

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|