“In the past couple years, I’ve gotten kicked off of PayPal and Venmo,” sex worker Maya Morena told me. “I’ve gotten kicked off Twitter. I had 80,000 followers on Twitter; I had 30,000 followers on Instagram, I had 30,000 on Tumblr. I lost all those platforms.”

Morena’s experience isn’t unusual, though it also isn’t well known. When the right talks about censorship, it focuses obsessively on liberals protesting conservative speakers. When the left focuses on censorship, it points to the efforts by red states to criminalise the teaching of LGBT and Black studies. The longstanding, and worsening, policing and censorship of sex workers online is seen by all as either justifiable or unimportant. It is neither though; the censorship of sex workers affects their livelihood, their ability to advocate for themselves, and puts their safety and their very lives at risk.

That’s why when Twitter started promising that Twitter Blue would boost visibility and engagement on the platform, many sex workers signed up. The service hasn’t really solved sex worker’s problems. But the hopes around it, and the backlash to it, demonstrate just how isolated sex workers are, and how much they need solidarity from those who care about free speech.

A Sustained Assault on Sex Worker Speech

Government, gatekeepers and the public have long been very uncomfortable with sexual speech, going all the way back to laws that criminalised the shipping of sexual material through the mail in the late 1800s.

The early internet gave sex workers the ability to advertise directly to clients and to be visible online in ways that had been previously unimaginable. Sites like Backpage and Craigslist allowed people to promote erotic services and, importantly, allowed them to vet clients. Homicides of sex workers cratered in cities where Craigslist opened erotic services websites as sex workers were able to get off the streets and out of danger.

Despite clear evidence that free speech made sex workers safer, policy makers and anti-sex advocates insisted, with little to back them up, that adult services on the internet contributed to trafficking.

The “watershed moment” for sexual censorship, according to Olivia Snow, a dominatrix and a research fellow at the UCLA Center for Critical Internet Inquiry, came in 2018, with the bipartisan passage of FOSTA/SESTA. These laws made platforms legally responsible for user-generated sexual content. That gave many platforms an incentive, or an excuse, to purge sex workers.

Backpage was shut down by the government in 2018; Tumblr purged most NSFW content the same year. So did Patreon. Payment processors and banks have been escalating a longstanding war on sex workers, preventing them from accessing funds or doing business. Even OnlyFans, which has built its business almost entirely on sex workers, decided to get rid of sexual content, though it reversed its decision after a backlash from creators.

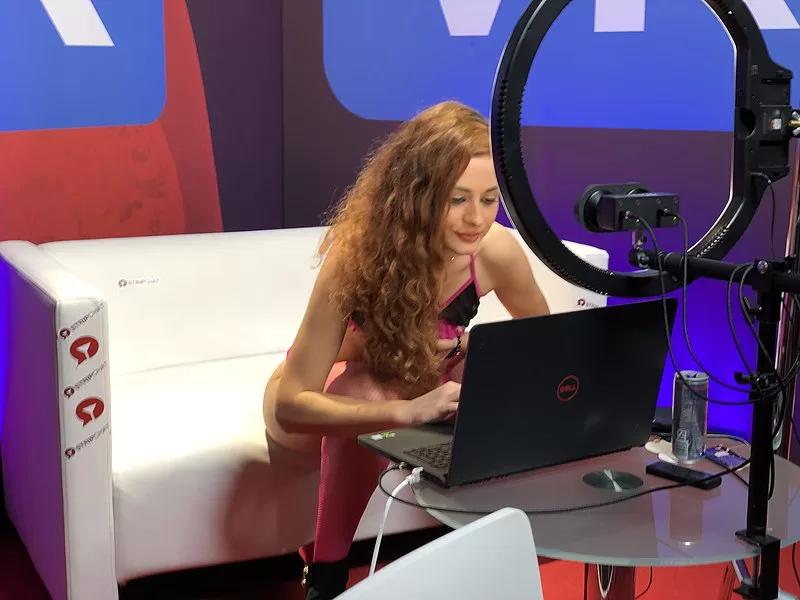

As sex workers have been shut out of most sites, Twitter has become more and more important to the community. “Twitter is the only major social media platform that tolerates us,” Snow said. “It is by default the least shitty of the platforms.”

Twitter Is Welcoming—But Not That Welcoming

A recent study found that 97% of sex workers rely on Twitter as their top site for finding followers. Writer and sex worker Jessie Sage explained that while she has accounts on sex worker sites like Eros and Tryst, “the people who book me tend to do so because they find me and then they go look at my socials.” Clients use Twitter to verify that sex workers are who they say they are, and to see if they have shared interests. And, Sage says, Twitter allows sex workers to share information. “Being able to connect with other sex workers allows us to create pathways and resources and screening resources for each other that keep us safe.”

Sage also says Twitter is vital because it lets sex workers show that they’re not just sex workers. “Most of my Twitter’s just talking about books I like to read and things that I’m thinking about,” she told me. “But there’s something very political about that, because I’m saying that I am a sex worker, and I’m also all of these other things. And when we get shoved off of social media, we lose that and we become dehumanised. And when we become dehumanised, our existence becomes much more ripe for abuse.”

While Twitter is somewhat welcoming to sex workers though, it’s not that welcoming. Sex worker accounts are often deprioritized by the algorithm (a process sometimes referred to as shadowbanning). Deprioritisation can mean that accounts don’t show up in search results or that they don’t show up in follower’s feeds. That makes it hard to build an audience. It can also make it easy for bad actors to impersonate sex workers and catfish clients. “Fake accounts on Twitter are able to get more followers than me, because I’m already censored,” Morena told me. “It’s a big problem for all sex workers.”

Twitter Blue to the Rescue, Sort Of

In December, new Twitter owner Elon Musk claimed that for $8/month, Twitter Blue users would begin to be prioritised in search and in conversations on Twitter. Many sex workers hoped Twitter Blue would give them more visibility.

Sex worker Andres Stones says that in his experience post-Musk Twitter has strangled his engagement and has “had a very large and negative impact” on his business.” It’s not clear whether this is because Musk is more aggressive in restricting adult content, or whether the new Twitter simply throttles engagement for everyone who isn’t on Twitter Blue. Either way, Stones says, “I started subscribing [to Twitter Blue] out of necessity.” It hasn’t gotten him back to where he was before, but it’s at least slowed the slide. “It’s been helpful only insofar as not having it was a death knell for engagement.”

Other sex workers report similar experiences. Morena says it hasn’t been that helpful, though it’s given her content an “extra push.” Sage struggled because Twitter Blue didn’t allow her to change her screen name easily, which made it difficult for her to advertise her travel dates.

Block the Blue

Sex workers saw Twitter Blue as a possible way to navigate censorship and deprioritisation on the one important social media platform that warily tolerates their existence. But in the broader cultural conversation, Twitter Blue was portrayed as a service solely for Elon Musk superfans and fascist trolls.

Mashable reported on a Block the Blue campaign, which encouraged Twitter users to adopt a Blocklist targeting all Twitter Blue accounts. It was embraced by NBC News reporter Ben Collins, Alejandra Caballo of the Harvard Law Cyberlaw Clinic and other large progressive accounts. Twitter comedian and celebrity @dril told Binder, “99% of twitter blue guys are dead-eyed cretins who are usually trying to sell you something stupid and expensive.” Blocking them, @dril suggested, was funny and a way to undermine Musk’s right wing political agenda.

But a small study by TechCrunch found that the vast majority of Twitter Blue accounts were not right wing harassment accounts. Instead, people used the service because they wanted features like the ability to post longer videos, or two-factor authentication—or because they were, like sex workers, businesspeople trying to boost engagement.

Ashley, a sex worker and researcher of online platform behavior who did her own study of Twitter Blue users, told me that the Block the Blue list is frustratingly counterproductive. The best way to block hateful trolls, she argued, is to block the followers of large right-wing troll accounts.

“I’m all in favour of users being empowered to block people,” she says, “but combined with the fact that so many sex workers are using this, [Block the Blue] is really just sharing a sex worker block list. Because there’s way more sex workers than hateful people on there.”

No Voice

Ashley adds that the majority of Twitter Blue users are probably just random people experimenting with the service. The point though is that sex workers are using the service at high rates, but have had little success in getting their interests, or existence, recognised by progressives who are supposedly fighting for marginalised people. Matt Binder, who wrote the Mashable article about Block the Blue, told me he doesn’t believe that sex worker concerns did much to interrupt or slow the Block the Blue campaign which has “become somewhat of a meme on the platform,” he said. (He added that he thinks more people block individual users than use the block list, and doesn’t think there’s been much “friendly fire.”)

Musk and the right are no friends to sex workers; as Snow told me, the right-wing “neo-fash, neo-Satanic Panic” targeting LGBT people is built on terror and hatred of anything associated with sexuality, which includes sex workers (many of whom are LGBT themselves.) But progressive leaders often don’t feel accountable to sex workers either, and mostly ignore sex workers when they say (for example) that blocking everyone using Twitter Blue will further isolate them.

Twitter Blue isn’t a solution. But it’s a reminder that sex workers face extreme and debilitating censorship. More people need to listen to them.