In the upscale Damascus neighbourhood of Al-Adawi, a blue metal door bears a sign reading: “The One Room Theatre.”

The entrance feels unwelcoming. The adjacent garden is frozen in time, suggesting abandonment. This impression deepens beyond the threshold – a cluttered “waiting room” overflows with scattered cassette tapes, faded playbills, film posters and yellowed newspaper clippings haphazardly pinned to walls and windows.

Dominating the wall in the theatre room, is a photo of identical twins, Mohamad and Ahmad Malas. Over 15 years ago, they dreamed of entering Syria’s theatrical scene. Rejected by state institutions that dismissed their vision, they converted a room in their family home into an intimate theatre. Small in size, vast in ambition.

Militias in support of former President Bashar al-Assad’s regime had occupied the house at some point during the Syrian civil war, according to Mohamad Malas, but family relatives later expelled them.

“When the regime fell last December we rushed back from a Jordan film festival,” he told Index. “Returning home was painful – the house stood looted and empty. Its soul has gone.”

Ahmad Malas recalls writing plays with his brother in 2009, inspired by their studies at a private Damascus theatre institute.

Under Assad’s rule, addressing direct political topics was forbidden, so they crafted humanist stories with whispered political undertones. After the Directorate of Theatres repeatedly ignored their licensing requests, they launched the underground One Room Theatre.

They hosted three plays, the last of which was staged shortly after Syria’s revolution began.

As protests surged, the twins joined the uprising personally, not only through art. Arrests and security threats followed, forcing them to flee Syria in late 2011. Heartbroken, they locked their theatre door. Months later, their family abandoned the home and headed to Saudi Arabia, leaving it silent.

The Malas Brothers drifted through Lebanon, Egypt and finally France, where they pursued theatre in Arabic and French. One play, The Two Refugees, serendipitously reached Damascus in late 2024.

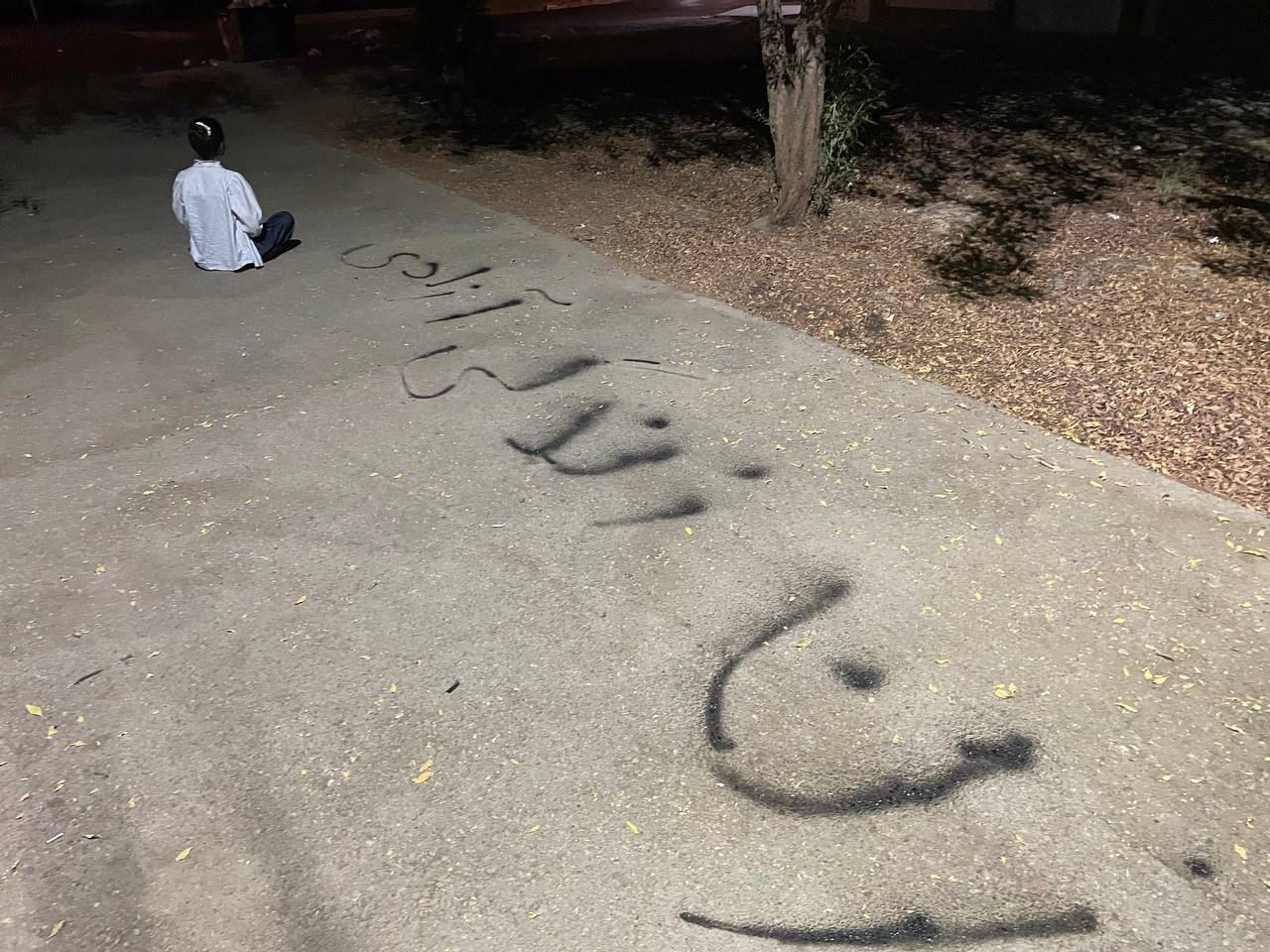

On their return, the twins deliberately left the waiting room’s chaos untouched – tapes strewn, posters peeling. Their only change was to move the theatre to a sunlit balcony near the kitchen due to Syria’s chronic power cuts. At 4pm, natural light frames their play All Shame Upon You.

Photo by Mawada Bahah

Mohamad Malas explained that the play, staged 20 times post-Arab Spring but paused in Syria, now features rewrites “we’d never dare perform before liberation”.

The performance unfolds on a crumbling sofa “stage” before low chairs. It follows two opposites sharing a flat: a heartbroken intellectual whose lover married during his imprisonment, and a crude soldier dreaming of martyrdom-for-glory. Their clashes blend rage, dancing and tears, culminating in the soldier forcing the poet to call his lost love.

The Culture Ministry has promised support – unlike the pre-revolution era when security agents monitored every show. Yet the twins remain pragmatic.

“The theatre in Syria doesn’t pay for bread,” Mohamad Malas said, adding that he and his brother will split time between France (to earn a living) and Syria (to follow their passion).

Their French passports offer global protection but “mean nothing in Syria,” he added. “If a French passport serves me better, our country is still on the wrong path.”

In their last show on 5 June, before they returned to France, the Malas brothers cautiously pushed boundaries, hinting at identity-based killings on Syria’s coast earlier this year.

In March, hundreds of minority Alawite civilians in coastal cities were killed by Sunni fighters, according to Reuters news agency reporting and several monitoring groups. Assad belonged to the Alawite sect, and the massacre came after a rebellion by remaining Assad loyalists, that ended in bloodshed.

The attacks took place only three months after Assad’s ousting in December ended his brutal rule and followed almost 14 years of civil war.

“Freedom isn’t just criticising the past regime,” Mohamad Malas said.

A pivotal line lingers in his play: “Was the homeland worth all this suffering?” When asked, Ahmad Malas admitted: “Sometimes, no, not after children died in Daraya, Ghouta… then again on the coast after the revolution.”

Despite Syria’s wounds, they harbour hope: “Mistakes happened, but awareness and law can heal rage.”

But despite the gloomy theme of the play, the Malas brothers struggle to hide their joy. The reason is that they’re finally able to stage work without censors hiding in the audience.