3 Sep 2017 | Index in the Press

The Council of Europe, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the Index on Censorship organization campaigning for freedom of expression have criticized Estonia this week for refusal to give accreditation to three Russian journalists to an European Union ministerial meeting to be held in Tallinn, Postimees said. Read the full article

3 Sep 2017 | Index in the Press

The Council of Europe, the OSCE and the Index on Censorship, an organization which campaigns for freedom of expression, have criticized Estonia this week for the country’s refusal to accredit three Russian journalists for an EU ministerial meeting to be held in Tallinn this month, daily Postimees reported. Read the full article

4 Jan 2016 | Estonia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features

In late November 2014, Estonia’s parliament made a historic decision to launch a Russian-language TV-channel as part of ERR, Estonia’s public broadcaster. A year later the channel is a reality: ETV+, ERR’s third channel debuted on 28 September.

The launch passed quite quietly, compared to the reaction that greeted the decision to create the channel. There were discussions about what the opening of a Russian-language channel in Estonia would mean. Would it be a tool of government propaganda or a knitting together of Estonia’s two communities, Estonian and Russian speakers into one community? From Russia there were clear expectations of a counter-weight to Russian media, which is widely followed by Estonia’s Russian speakers.

Speaking at a media conference hosted by ERR in June 2015, the ETV+ chief editor Darja Saar — a Russian project manager with no media experience — described the goals of the new channel: “We gave up the classical media rules from the very beginning, when we decided that we are not going to tell people what is right or wrong. Instead, we will follow people’s wishes – they are tired of just words and want deeds.”

The new TV channel aims not only to be an informer, educator and entertainer in the mould of a classical public service broadcasting channel but a leader in society and a hands-on problem solver.

In its two months on air, though, ETV+ has operated mostly as a traditional TV-channel offering morning programmes, debates, films and news. As required by law, all programmes are subtitled in Estonian. While geared toward Estonia’s Russian speakers, the station’s audience is mostly ethnic Estonians. In its debut week, ETV+ attracted 294,000 viewers. Ethnic Estonians accounted for 217,000 of the total and the other 77,000 were other ethnicities. On an average day during its first week 97,000 watched ETV+. On 28 September, its first day, 120,000 tuned in to sample the new station’s offerings.

ERR board member Ainar Ruussaar pointed out that ETV+ is a long-term project to improve Estonian society and was not about ratings. Yet the failure to draw a larger share of the Russian-speaking audience in the country may put that mission in jeopardy.

ERR has a fraught history with Russian-language programming. Promotion of Estonian language and culture has always been one of its core values. This served it well while it was under the Soviet system. Later, it countered Russian propaganda. But while times changed, ERR did not sufficiently move away from its core. In the early 2000s, the broadcaster, then under budgetary pressures, cut its slate of offerings in Russian. For years after its sole Russian-language production was a little-watched news programme.

In 2007, there was a serious discussion about launching a new Russian-language station after the 27 April violence sparked by the removal of the Bronze Soldier, a World War II memorial in Tallinn’s city centre. Then the political decision in favour of the Russian-language channel in Estonian Television was only one step away and there was readiness in the Russian-speaking audience to watch it. But as the riots faded, funding to get the project off the ground faltered and the opportunity to tie Russian speakers into ERR was missed. The country’s then prime minister Andrus Ansip said it was too difficult to compete with Russian TV channels so ERR’s Russian-language offerings would be limited to radio.

ETV+ is dancing on the razor’s edge. If it covers politics too much it will raise the ire of politicians who could cut its funding. Too much pro-government propaganda could turn off the Russian-speaking audience. Lurking in the background are ratings challenges that could force it to air infotainment and entertainment programmes.

As ETV+ turns two months old, it remains to be seen how it will develop. But connecting with Estonia’s Russian-speaking citizens must be its first goal.

This article was originally posted at indexoncensorship.org

This article was updated on 5/1/16 to clarify ETV+’s viewership numbers.

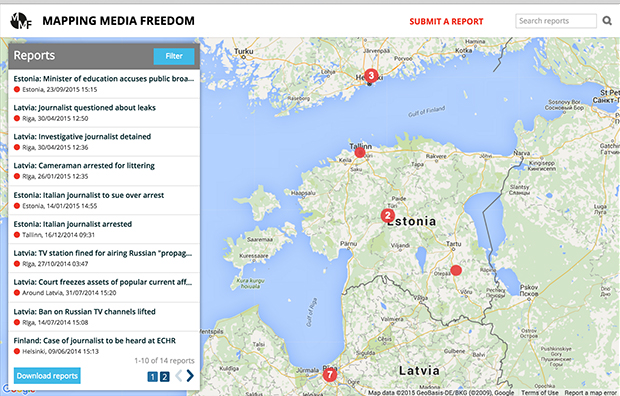

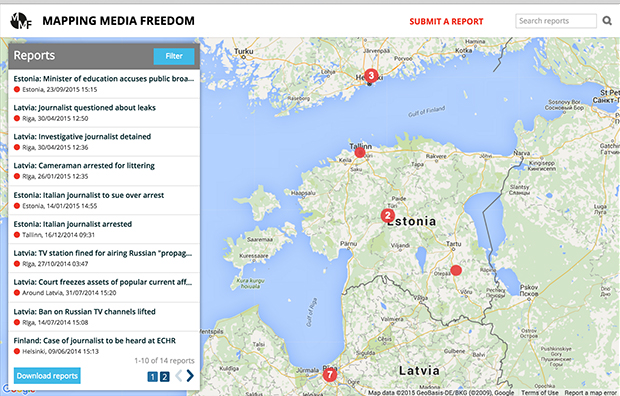

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

2 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News and features

On 19 September, the Estonian Minister of Education, Jürgen Ligi, accused the Estonian Public Broadcaster’s new Russian-language TV channel of disclosing secret government data.

The news report that sparked Ligi’s accusation dealt with the government’s proposal to teach high school students in Estonian. This move has been seen as ignoring the rights of the Russian-speaking minorities in the country.

Ligi implied that the report caused difficulties for the government. He also announced that, as the information was most likely leaked, there would be an official investigation. The head of the news department at the public broadcaster ETV, Urmet Kook, has already explained that the information was not received through a leak but was discovered during a routine check of public documents on different ministries.

This is the latest in a series of actions by the government against the media for disclosing data. Politicians see themselves as having a monopoly on truth and consider the press as nothing more than troublesome meddlers.

There are no specific laws relating to the media in Estonia, so all commercial outlets — apart from broadcast channels — are governed like any other business. The diverse legal landscape is subject to many different interpretations and there are no defined meanings of terms like ‘public interest’ and ‘public figure’, which makes it difficult for journalists to operate.

A typical example of the excessive limitations on the media is the Act on Defence of Personal Data. On first glance, it appears to be a noble attempt to defend sensitive information about the private lives of individuals, such as political affiliations, race and heritage. However, a closer look shows that it effectively prevents many journalists from uncovering information in the public interest. For example, a hospital denied a journalist access to information relating to a lump sum payment made in compensation for malpractice. In another case, a press officer at the Office of Public Prosecutor refused to acknowledge a criminal investigation into a well-known businessman. On both occasions, the reason for refusing to disclose the data was its sensitive nature.

Some caution is understandable. Any ethical person understands the necessity of the right to privacy. But over zealous and arbitrary enforcement makes it very difficult for journalists to warn the public of corruption, crime and dangerous individuals. With the protection offered by the act, released convicts can demand media outlets remove a story relating to their crimes, trials and sentences. Offenders can effectively hide in plain sight.

While these legal hurdles are a fact of life for many journalists, freelancers face extra obstacles. Larger media companies are given preferential treatment by the government, as are journalists who present information in the desired way. Estonian media channels also tend not to work with freelancers on a one-time basis. Such practices hurt freelance journalists, especially younger writers who lack established sources and connections. Without proper access to information, they are deprived of a proper livelihood.

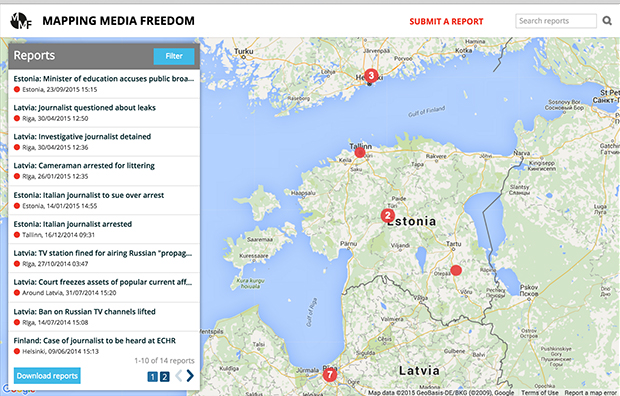

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|