7 Nov 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

What is worse: intelligence services gathering data without any legal basis or secret services operating within a legal framework that allows them to obtain vast amounts of personal information? This is the key question regarding Germany’s surveillance apparatus, as a new law regarding its foreign intelligence agency, the Federal Intelligence Service (BND), was passed through parliament on Friday 21 October.

Following the 2013 uncovering of the mass-scale surveillance by America’s National Security Agency, including details of the tapping of German chancellor Angela Merkel’s phone, there was a sense in German public debate that secret services were out of control. In early 2014, a parliamentary committee was established in the national chamber of the Bundestag to investigate the scale of surveillance activities of foreign intelligence in Germany. Attention soon shifted to the role of the BND, after former NSA employee Thomas Drake called the agency “an addendum appendix of the NSA” in his testimony to the committee in July of that year.

While the German government began the process to reform the legal framework of the BND, the governmentally-appointed officer for data protection and freedom of information took a closer look at the work of the service’s telecommunications unit in the southern town of Bad Aiblingen.

What it found was remarkable: across 60 pages, the expert report from March 2016 listed legal breaches by the BND. Although the intelligence service had been “repeatedly and heavily obstructing my work”, the officer was able to gain a picture full enough to pinpoint 18 “serious transgressions” and submit 12 official complaints, which, according to the investigative tech-blog Netzpolitik.org, is a record unrivalled by any governmental office in Germany to receive at one point in time.

Netzpolitik.org also made public the “top secret” labelled report in September.

Surveillance-critical civil society in the country may have been hopeful to see the intelligence service face consequences for past transgressions and future limitations for its activities. They were in for a surprise, though, as the BND law put forward in June this year proposed to legalise all surveillance activities that had thus far been taking place and further expand their scope additionally. The new law allows the foreign secret service thus-far illicit in-country surveillance.

In theory, any German-to-German communication would have to be excluded from surveillance, but two independent reports by experts, including one by Chaos Computer Club, found that online traffic does not carry a clearly discernible nationality. The constitutionally stipulated freedom of privacy of communication suddenly appears less convincing. It also follows that any non-EU national is not considered bearer of fundamental rights enjoyed, on paper, by anyone living in Germany, as all electronic communication including at least one foreign-based party can now be analysed and stored for up to six months, including all metadata. This will include foreign journalists and the sources they are in contact with. The previous 20%-rule, whereby the BND was limited to only intercept and analyse so much of the traffic available, was lifted altogether. The extended competencies were not left without a new and grand mission: surveillance can now take place to reap “insights into foreign and security policy [which] may be of relevance”.

Senior investigative journalist David Crawford spoke to Index on Censorship about an opportunity missed in the sense that the “legislative process had not been used as a forum what intelligence services should do but…to legalise practices that were already going on”. A “silent consensus” across the grand coalition seemed to exist and it appears that policy-makers close to the intelligence services had successfully dominated the reform process and delivered a law tailor-made for the BND.

Although the result may be unsatisfactory Crawford said that, in the German context, it was generally “positive to write down the rules of behaviour” for a practice that have been ongoing for decades and employed by more resourceful intelligence services worldwide. While especially the aspect of information sharing between foreign secret services appears worrying to Crawford, the investigative journalist points out that this professional group never had any “real protection, they are treated like any citizen” under German law. Thus, he emphasised that no journalist should pass the responsibility for safeguarding his or her sources to the state law or EU regulations: “It is up to the person to get the training they need, to put a lot of thought into how they can do this without somebody getting hurt”.

While extensive electronic surveillance by multiple states has to be reckoned with, regardless of a legal basis for the practices, the journalist should employ the right kinds of “tricks of the trade” to make sure that any whistleblower who helped uncover a story will, under no circumstances, suffer: “a lot of the time it is just going out meeting people, not using the phone, not even using the mail…I figure out a way to meet them, knocking on people’s doors or meeting them in a supermarket or somewhere, where you are unlikely to be monitored and they would feel a lot more comfortable talking…Use less technology, use a pencil, cite documents rather than announcing you have a whistleblower.”

According to Crawford, the lack of investigative journalism in general and the unawareness of some journalists engaging in serious investigative projects may be at the root of a sloppiness with the more time-consuming methods that the job requires in a reality of surveillance.

However, civil society activists maintained a responsibility of ethics reflected in legislation and protested with petitions and a solemn vigil on the evening prior to the final vote. As the law was being passed on the morning of Friday 21 October, the former liberal justice minister Sabine Leutheuser-Schnarrenberger announced constitutional charges against it. Meanwhile, the German intelligence service has other legal cases pending against it: the worldwide largest data transmission exchange business based in Frankfurt, DE-CIX, is seeking to get a “judicial review for the practices of telecommunication surveillance” for its customers. Another lawsuit filed by the German branch of Reporters Without Borders in June last year is based on the office for data’s annual report for 2014 and is seeking to defend all journalists and their sources against the transgression of the privacy of communication as an attack on press freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”3″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1478541493543-29b41d55-076a-3″ taxonomies=”6564″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

5 Jun 2015 | mobile, Youth Board

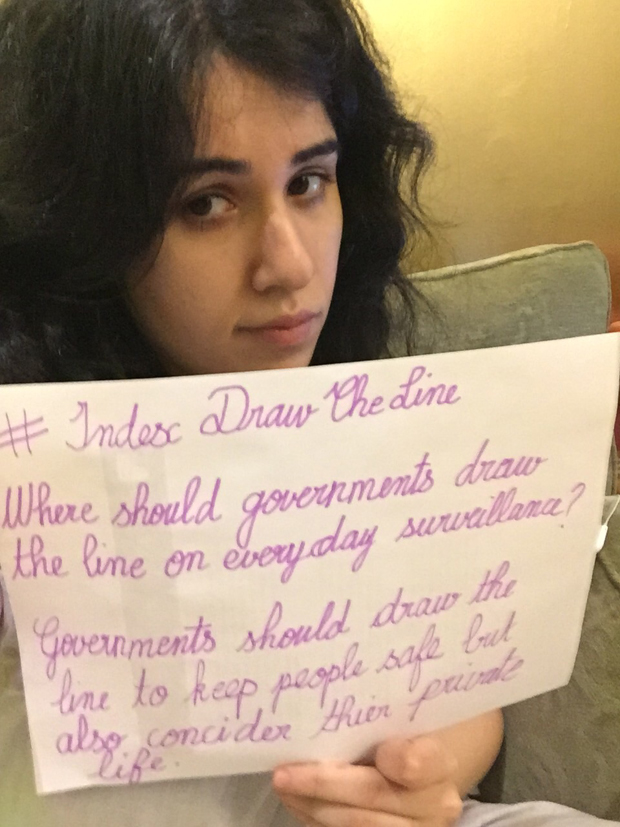

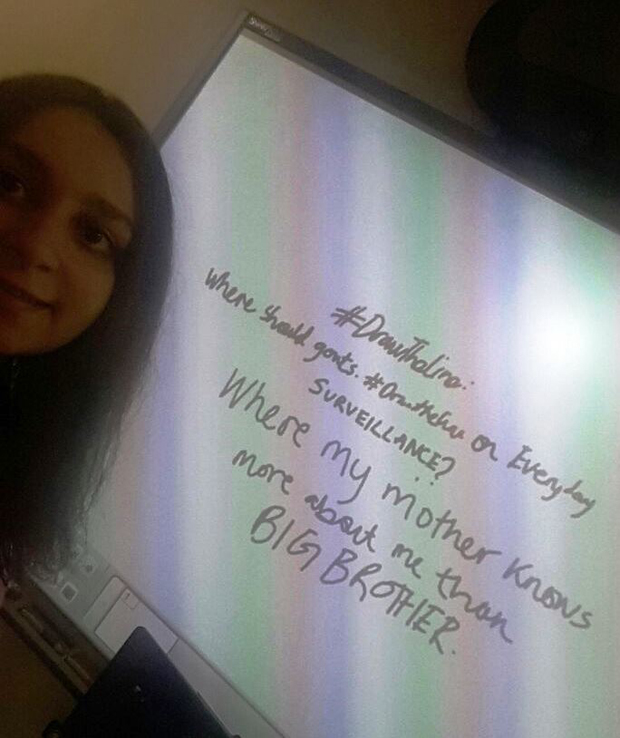

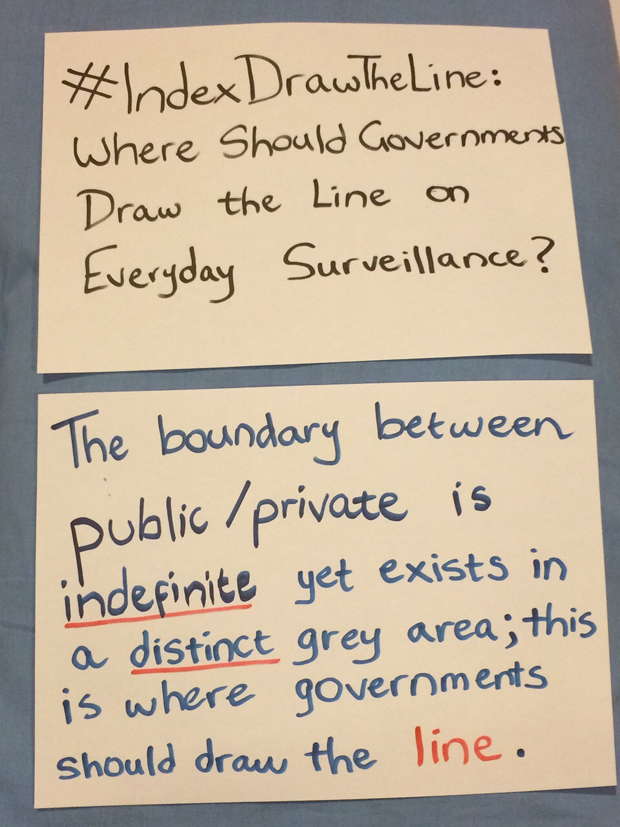

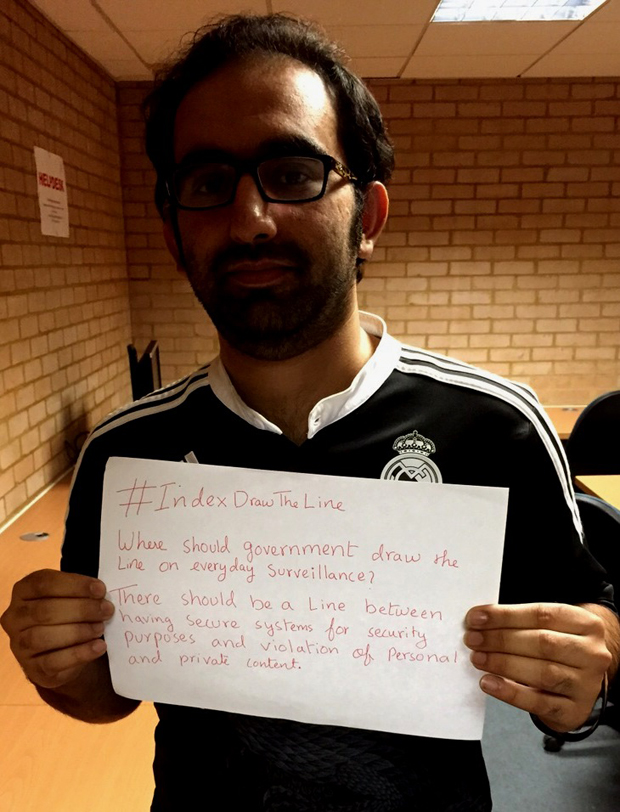

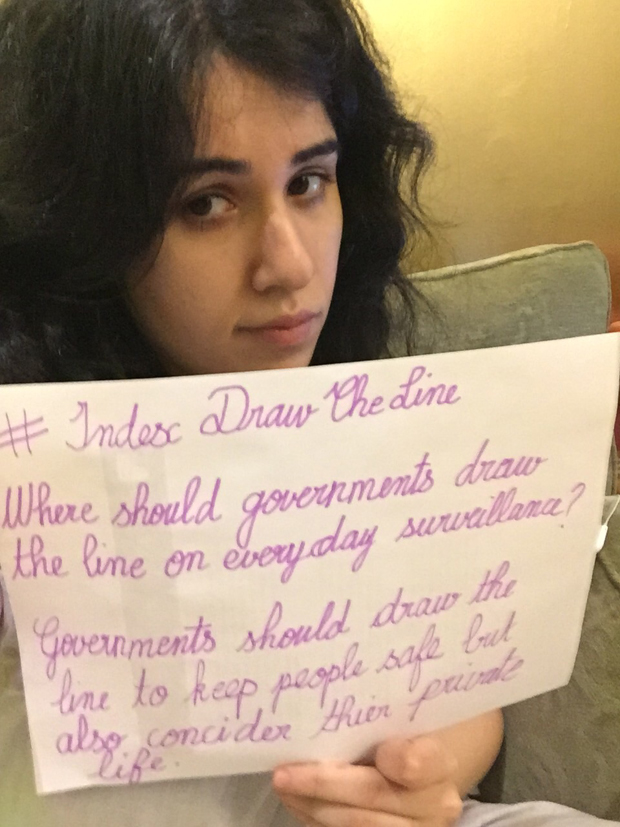

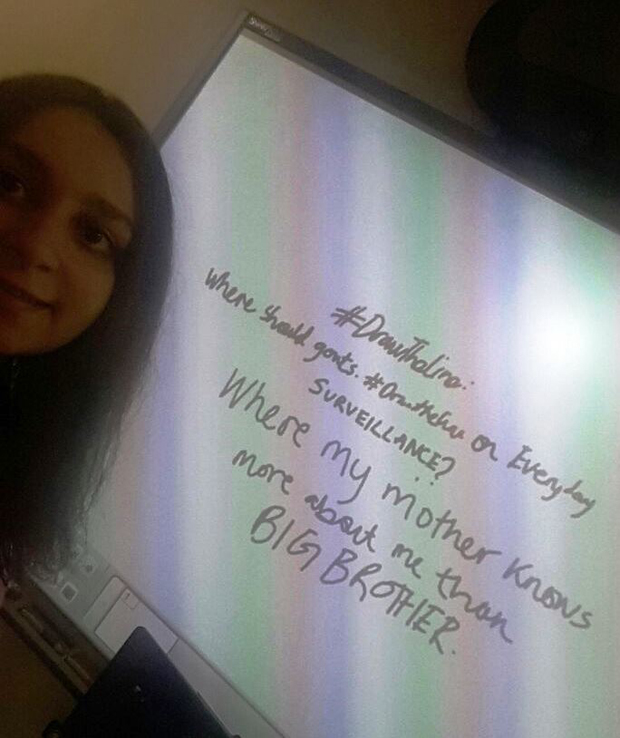

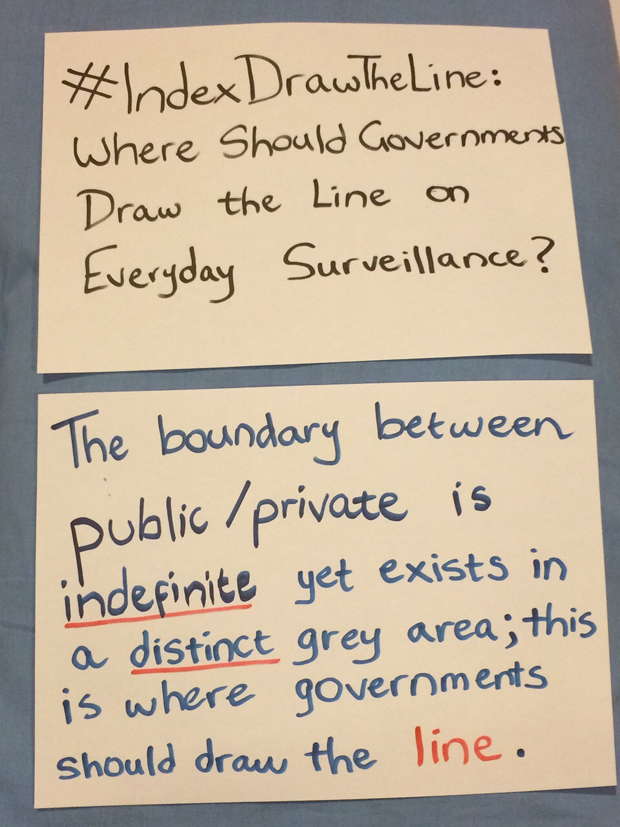

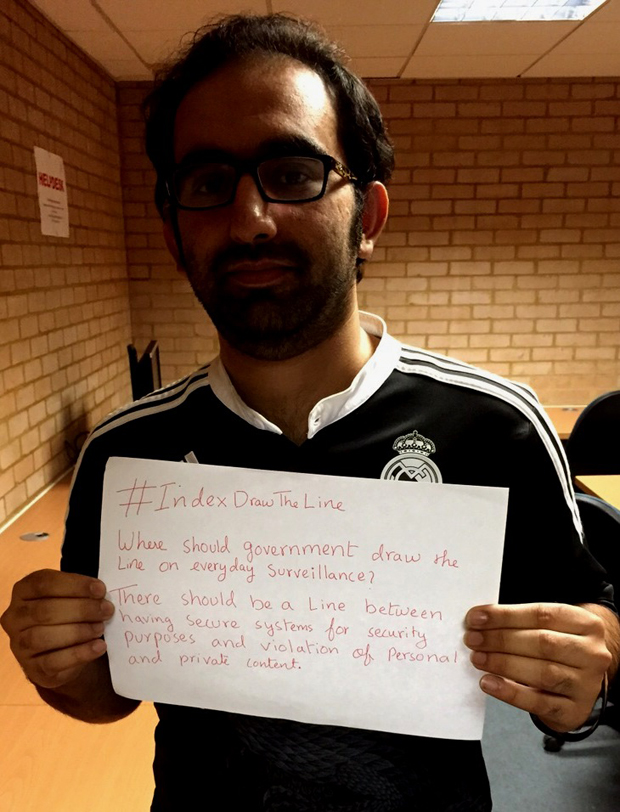

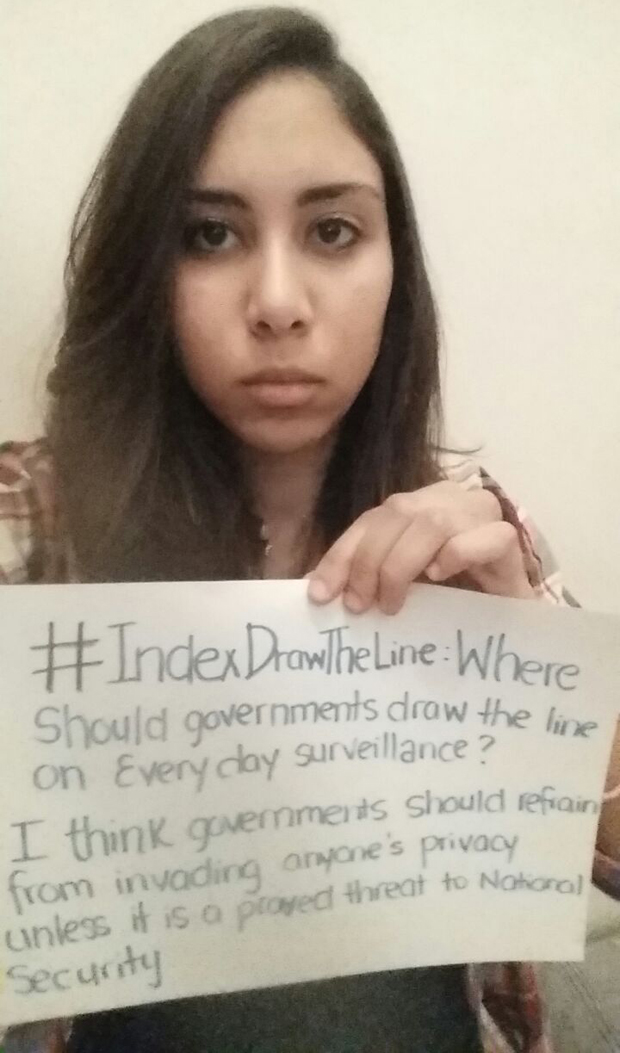

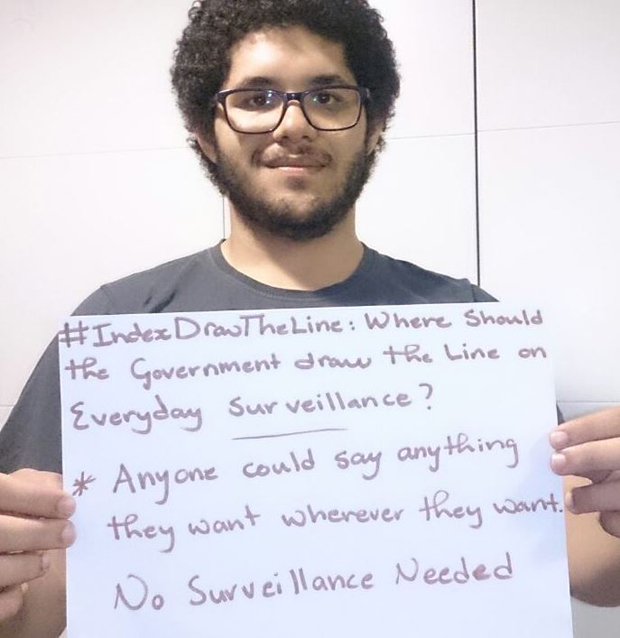

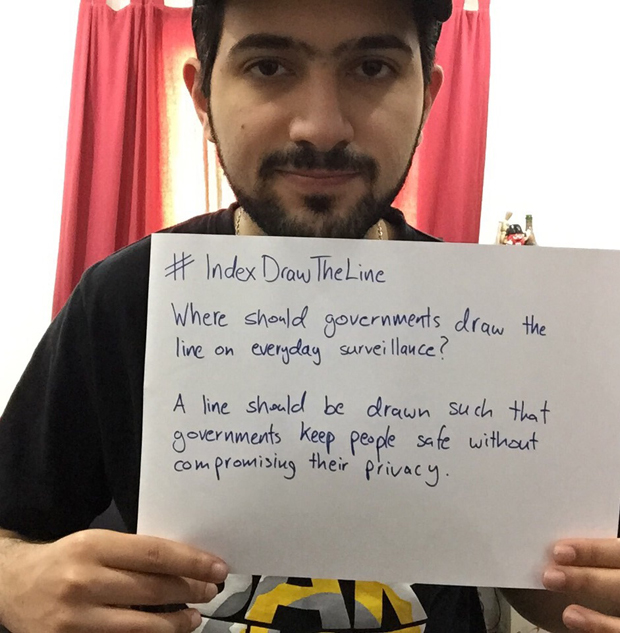

In the latest #IndexDrawtheLine, we’ve been asking the question: where should governments draw the line on everyday surveillance?

Mass surveillance has been a controversial issue, notably since former contractor for the US National Security Agency (NSA) Edward Snowden leaked information about the agency’s domestic spying. Today, some governments worldwide monitor phone calls, text messages and/or social media communications within the countries. Granted, mass surveillance may well be beneficial for governments to fight terrorism and ensure national security, but some people are concerned about the invasion of their privacy and personal life.

As well as the debate about this question on Twitter, we asked some students based around the world to give us their views. The students and their respective views can be seen in the form of photographs below.

One user on Twitter argued that the line should be drawn as per the law and added, “This right of OURS ‘…shall not be violated and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause'” referring to the fourth amendment to the United States constitution.

Other responses suggested that governments should be able to ensure national security without invading the privacy of the people. One of the students below argues that the line should be drawn so that “my mother knows more about me than BIG BROTHER”, referring to the leader of the fictitious state from George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The general consensus seems to be that government surveillance should not happen unless it is proved there is a genuine threat to the safety and security of the people.

This article was posted on 6 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

18 May 2015 | Digital Freedom, Draw the Line, mobile

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden attempted to explain mass surveillance through a conversation around dick pics during an interview with John Oliver on Last Week Tonight, a satirical current affairs show aired by American network HBO.

“Even if you sent it to somebody within the United States, your wholly domestic communication between you and your wife can go from New York to London and back and get caught up in the database,” Snowden said in the interview, conducted in his temporary residence in Russia after the United States cancelled his passport for leaking details about NSA domestic spying in June 2013.

The elimination of complicated terminology in the discussion has allowed us to understand that although emails sent between Gmail accounts are encrypted and unidentifiable to outsiders as they move from Google’s data centres in the US and across the world, in reality the racy pictures embedded in these emails can actually be stored in several data centres worldwide as a way to provide backups in case one centre fails.

These encryption techniques have been around since 1991, when hacker Philip Zimmermann uploaded a free encryption program called Pretty Good Privacy – better known today as PGP – to the internet. Using a form of cryptography developed in the 1970s known as public-key cryptography, users are given a public key that can be shared which encrypts messages that are sent to them, and another one they keep private to decrypt messages they receive.

As public-key cryptography was generally reserved for military and government use prior to the release of PGP, the availability of these advanced encryption algorithms to the general public was a significant step in the realm of free expression at the time. But while web-based communication has become part of daily life, the average citizen is only beginning to grapple with the idea of mass surveillance let alone the tools associated with it.

Should individuals accept the surveillance environment, allowing – for example – government officials to obtain personal photographs shared between two consenting adults through a corporate service, as raised by Snowden?

Just months before Snowden blew the whistle, India began implementing a Centralised Monitoring System in April 2013 to monitor all phone and internet communications in the country. Following his disclosures on mass US secret surveillance programs, other governments around the world such as Brazil and Russia began debating on how to pressure companies to store user data locally. During this period, Turkey began drafting new regulations that would make it easier to get data from internet companies following the eruption of Gezi Park protests.

To what extent is it possible to escape everyday surveillance amidst these developments and how would this affect our communications? And even if technological advancement brings us newer tools providing stronger privacy protection, where should governments draw a line in monitoring what we share with friends and family?

Join the discussion on twitter with #IndexDrawTheLine

15 Sep 2014 | European Union, News, United Kingdom

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (BIJ) filed an application on Friday with the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg challenging current UK legislation on mass surveillance and its threat to journalism.

Lawyers Gavin Millar QC at Doughty Street Chambers, Conor McCarthy at Monckton Chambers and Rosa Curling at Leigh Day solicitors have been assisting the BIJ with its investigation. The group argues that UK legislation imposes constraints on journalistic free expression and does not offer enough protection for journalists’ sources, therefore it is in breach of Articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

Information uncovered by American whistleblower Edward Snowden appears to highlight how developments in mass surveillance could pose a major threat to the process of journalism. Rules for the interception of data are set out in the Regulation of Investigative Powers Act (RIPA), however, this act does not offer enough controls or checks for external communications. Therefore, any information exchanged through services such as Gmail, Google Docs and Dropbox may not offer the level of confidentiality expected, the group wrote in their application to the ECHR.

It is not only communications which may be scrutinised by the government or secret services; they also have access to metadata, which is the data generated as you use technology. It includes information such as the date and time of phone calls and where emails are sent from. Metadata can be linked to sophisticated computer programs which can enable the user to collate masses of information, building an intricate picture of an individual or organisation’s movements, contacts, sources and lines of enquiry.

According to BIJ, the main implication of unregulated mass surveillance is that journalists can no longer offer anonymity to their sources, or assume that their work is confidential until publication.

This is further compounded by the number of the situations where it is deemed appropriate for surveillance techniques to be enlisted are vaguely defined within the law. It states that data can be intercepted where it is believed that the security or economic interests of the state are involved, meaning investigative journalists especially have to be cautious when covering topics which may be of interest to the government and the intelligence services.

Currently, the BIJ believes the only way in which journalists can be sure they are protected against mass surveillance is to do all of their communications in person, without the use of electronic devices – something which is often impossible, especially if sources are based outside of the UK.

However, under the ECHR journalists should be able to expect protection, the BIJ asserts. At the very least, the group said, this application will spark high-level debate within the government about how journalism and freedom of expression can be protected when governments are using advanced surveillance.

The BIJ says: “In the long term we would like to see proper regulatory control and scrutiny of how the intelligence services use mass surveillance to ensure these techniques and technologies are not being used to hamper legitimate journalistic investigation and inquiry.”

This article was posted on Sept 15, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org