26 Feb 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Russia

1. The fifth ring malfunction

(Image: Jaroslav Francisko/Demotix)

The lighting rig which proudly illuminated one less Olympic ring than it should have caused considerable embarrassment for the Russian organisers of the opening ceremony, as Sochi 2014 opened its gates to the athletes. Known as the “stubborn snowflake” Russian viewers at home were greeted with footage from the Opening Ceremony rehearsal, so they were none the wiser. The Russians later showed their funny side by only featuring four rings in the Closing Ceremony performance.

2. Pussy Riot getting whipped in the face

(Image: Sky News/YouTube)

While pre-emptive arrests meant many activists were unable to protest at all, five members of the punk group Pussy Riot and their cameraman were attacked by Cossack security patrols as they performed under a sign advertising the Winter Olympics.

Footage showed Cossack security staff whipping band members, pulling off their ski masks, and throwing them to the ground.

Russian deputy prime minister Dmitry Kozak dismissed the attacks: “The girls came here specifically to provoke this conflict,” he explained. “They had been searching for it for some time and finally they had this conflict with local inhabitants.”

While the international media covered the face-whipping incident in fairly minute detail, Russian press clippings about the arrest are hard to come by. Pussy Riot’s previous stunt in Moscow’s main cathedral, which landed them with a jail sentences and heavy fines, have already been scrubbed from the internet.

3. Justin Kripps’ website

(Image: @justinkripps/Twitter)

Russian fans hoping to keep updated by the Canadian bobsleigher’s website were disappointed, as Russian censorship authorities blocked access to it. It’s still unclear why, but it may be linked to a risque photo Kripps tweeted a month prior to the Games. The snap featured his burly four-man bobsled team in their underwear at a weigh in. The photo went viral, in particular within the gay community.

4. Almost every story about corruption, gay-bashing, forcible evictions and the environment

(Image: Heather Blockey/Demotix)

While the run-up to Sochi might have been dominated by negative stories in the Western media, with tales of homophobia, corruption and environmental destruction, local journalists had to be a lot more cautious when reporting the “true” face of Sochi. Strict surveillance measures were imposed on all journalists’ emails, social media and internet use – to keep any negative stories from breaking.

“It seems to me that some of these surveillance measures were conscientiously made public … to send a message,” commented investigative journalist and security services expert Andrei Soldatov while at the Games.

Self-censorship, he says, has become a “big problem” among local reporters and investigative journalists – who often felt scared to report on the wider political context of Putin’s games. “There are some fears that Sochi was a test ground … these kind of measures may be made commonplace in other parts of Russia,” he added.

BONUS: And…Russians accuse US of censorship and malicious media bias

(Image: Screenshot)

Censorship during NBC’s coverage of the Opening Ceremony included missing out a live performance by girlband t.A.T.u, omitting a Russian police choir performing Daft Punk’s “Get Lucky,” deleting Communist-themed vignettes, and failing to air a congratulatory speech by IOC chief Thomas Bach, praising the Russians. Russian media whooped with glee when the hashtag #NBCFail started trending on Twitter in response to the censorship.

American magazine The Nation published a rare honest analysis of the American media’s vitriol against Russia, noting that even before the Games began, the Washington Times had written off the venues as a “Soviet-style dystopia” and warned in a headline, “TERRORISM AND TENSION, NOT SPORTS AND JOY.”

Provocative BuzzFeed headlines like “Photographic Proof That Sochi Is A Godforsaken Hellscape Right Now” and the Twitter account @SochiProblems, provoked outrage in Russia. One Russian netizen took such offence with @SochiProblems that he travelled to London and created his own photo tour of the city “in Sochi style”. “The Other Side of London, where the guided tours don’t go” is a depressing trip through some of London’s worst outer districts. The results (translated from Russian) make for sombre viewing, tinged with humour.

The infamous double toilet in Sochi also has a doppelganger in London, as one Russian Instagram user, living in the capital, proved. The side-by-side facilities, identical to the toilets which athletes had endlessly mocked in the Olympic village, were installed in a typical upmarket hipster cocktail bar.

This article was posted on 25 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

22 Jan 2014 | Magazine, Volume 42.04 Winter 2013

Pussy Riot supporters prevented from praying for Putin’s resignation outside the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow (Image: Anton Belitskiy / Demotix)

Two issues preoccupying post- Soviet society are a wish to oppose outside influences (mainly from the West), and to resist aggressive behaviour in matters of religion. It is not difficult to point out inconsistencies and contradictions in these approaches, but more germane is the fact that both have survived, if in modified form, to the present day. When the possibility of further restrictions on freedom of conscience are being discussed, a key topic is invariably the need to protect society from the “expansionism” of new religious movements and radical Islam.

The arrests of members of the Pussy Riot punk band after their performance outside Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour proved a powerful catalyst for both these concerns. The protest was seen as a frontal attack on “tradition” by “pro-Western forces” (the actual point Pussy Riot wanted to make was neither here nor there), and as an attack on the religious sensibilities of the “Orthodox majority”. The reaction was accordingly heavy-handed, including not only imprisonment of two members of the group, but also the passing of a law criminalising the “offending of believers’ religious sensibilities”, often referred to as the “blasphemy” law.

The legislative proposal was introduced in September 2012 and became law in August 2013 but has not yet been enforced anywhere. There may be at least two reasons for this. First, many laws that are aimed at NGOs, protesters or what is seen as the “opposition” have either been applied much less rigorously than expected or not at all. The authorities have chosen not to resort to wholesale repression, preferring intimidation. Second, the Russian state and its political elite are still very secular and feel uncomfortable about what is widely regarded as a law against blasphemy.

Strictly speaking, this is not a law against blasphemy, unlike, for example, similar legislation in Italy. The offence is not against religious doctrine, the deity, or things considered holy. Desecration of sacred objects is an offence not under the Russian Criminal Code, but under the code of administrative offences, which means it is seen as less serious. Offending religious sensibilities or beliefs is a crime in the penal codes of several European countries, but the European Court of Human Rights (and, following it, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe) has consistently confirmed that a distinction needs to be made between offending sensibilities and inciting hatred.

In Russia today there are still attempts to bring charges of incitement to hatred under Article 282 of the criminal code in incidents that the law enforcement agencies, victims or others might reasonably have been expected to regard as mere offences against religious sensibilities. In a few cases, charges have been brought and, in fewer still, these charges have led to convictions. From interviews with law enforcement officers and representatives of various religious organisations, it is evident that numerous individuals and organisations that feel they have been offended on religious grounds appeal to the police and prosecutor’s office to institute criminal proceedings under Article 282. These requests are almost invariably turned down, and this is not a matter of officials taking sides: they are simply reluctant to institute proceedings on a shaky legal basis, except when that is in their own self-interest. They will do so if there is pressure on them from above, or if they face a pressing need to meet some target.

The addition of this new article to the criminal code, if it is not repealed, will lead sooner or later to its being enforced, and the main source of litigation will be complaints from numerous indignant parties. Demands for charges to be brought rained down upon the prosecutor’s office and police even before the amendments became law. It is important to recognise that the problem is not only repressive intentions on the part of the authorities, but also the repressive instincts of Russian citizens. Representatives of a wide range of community interest groups (though, thankfully, by no means all), including a number of minorities, constantly demand that criminal prosecution be the main way to influence those who cause them offence.

If the system does start enforcing this law, freedom of conscience will come under immense new pressure because of the likelihood of the sheer volume of litigation. Enforcement is likely to be highly selective, because a law of this kind can only be applied selectively. It will be manifestly discriminatory, in accordance with some individuals’ personal preferences and depending on the government’s latest priorities. Finally, it will be completely chaotic, because complaints will come in from all directions and there is nobody remotely qualified to assess their merits.

We can hope, of course, that the new article may yet be removed from the criminal code, but the chances of that are slim. The fact that it is there in the first place results from a consistent trend towards restricting freedom of expression in matters of religion, justified on the basis of the need to maintain “religious peace”. There are two main aspects to this laudable aim, and they enjoy widespread support. The first is safeguarding national security against the preaching of terrorism motivated by religion. The second is to safeguard national security against internal, particularly ethnic, conflicts, which are seen as often being fuelled by religion.

These two security aspects were major reasons for the introduction, in 2002-2007, of the current legislation to counteract “extremism”. This legislation is used extensively against violent racist groups, but also against sundry ideological minorities, which by no means espouse violence or pose a serious, or indeed any, threat to national security.

Abuse of this legislation is made possible by its imprecise wording, which we also find in respect to the new law to protect religious sensibilities. This inevitably leads to arbitrary application and, specifically, to exploitation for political purposes. There have been numerous instances of this, but let us focus on just three. Among the first major “anti-extremist” trials associated with religion were those targeting contemporary art exhibitions at the Andrey Sakharov Museum, which presaged the Pussy Riot case. Also, in 2011, a journalist was convicted for making rude remarks about believers in general, and the clergy in particular, even though his was not by any means a high profile protest and could not be represented as involving incitement to hatred against any group. Lastly, over several years there has been a serious campaign of criminal prosecution against people who read or distribute the works of a Sufi teacher, the late Said Nursi, even though neither he nor his Russian followers have links to terrorism, or engage in conduct which might constitute a threat to society.

In the case of the Sakharov museum exhibitions, the general public could at least understand more clearly what was going on. Some might consider the exhibition a profound artistic meditation on relations between the church and society; others might see the exhibits as an amusing send-up of the church and/or orthodoxy; some might consider it a send-up in bad taste or even an attack on the church, but within acceptable limits of freedom of expression; others, however, were determined to prove that the exhibition was a criminal incitement to hatred of orthodoxy and Orthodox Christians.

In the case of the persecution of followers of Said Nursi, the general public know nothing about the subject and must either just believe or disbelieve what they are told by the security services, believe or disbelieve what is said by Muslim leaders defending those being persecuted, or simply turn and look the other way. Most people choose the last option, including a majority of journalists,which means a majority of citizens, even those who take an interest in social matters, know nothing about these prosecutions.

Our citizens’ understanding of the issues around freedom of conscience is fragmentary. Most are far more concerned about conflicts over the balance between the slow-but-sure process of de-secularisation and the constitutionally guaranteed secular nature of the state. There are controversies over the presence of religion in schools, about the erection of Orthodox churches and mosques (although in the case of mosques the main cause of dissension is racism), and about various symbols of the cosy relationship between church and state. The real-life problems facing religious groups and, more generally, people expressing an opinion about religion, get forgotten.

These problems are legion. The most acute in recent years have arisen from improper application of anti-extremism legislation, but there are also the more “ordinary” problems, like refusals to release building land for places of worship and systematic campaigns of defamation. In a number of cases, like that of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, all these problems come together.

The Federal List of Extremist Materials has, however, excited the public’s interest by its scale and, even by Russian standards, sheer absurdity. The list can be found on the website of the Ministry of Justice and itemises materials banned from mass circulation. The ban is imposed by courts at the insistence of local prosecutors, who must satisfy the court that the material contains elements that can be construed as constituting “extremist activity”. This is usually incitement to hatred of some sort, impugning the dignity of a group, asserting the superiority or inferiority of a particular religion, and so forth. The whole process is quite remarkably ineffective and does not stand up to scrutiny. Most of the materials the list is seeking to ban cannot be identified from the titles given and, no less problematically, banning them does not in strictly legal terms mean they cannot be re-published, because a new court case would be needed to re-establish the identity of the materials.

A great many of the banned books, websites, videos and material involves religion in one way or another. Many are jihadist texts openly calling for terrorism or other forms of violence, but many have nothing prejudicial in them: perhaps at most a claim of the superiority of one set of beliefs over others, to which texts of Jehovah’s Witnesses are prone. There are works by Muslim authors well known for their contribution to jihadist ideology, but on topics that are of no concern to national security (most commonly, on aspects of Sharia law). Finally, a number of texts have found their way on to the list purely by chance, having been confiscated from some “wrong-thinking” individual. This explains the presence of medieval treatises by the likes of the Persian mystic al Ghazali. In 2013 there was even a ban imposed on one of the most popular translations of the Quran.

The absurdity of such methods of “fighting extremism” has obliged even President Putin, at a recent meeting with muftis in Ufa in Bashkortostan, to acknowledge that there are problems with the current approach to banning religious materials. Alas, there is no sign of willingness to review the methods of fighting extremism more generally, or those aspects of them that most blatantly violate freedom of conscience.

Translated by Arch Tait

This article appears in the Winter 2013 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

14 Jan 2014 | News, Russia

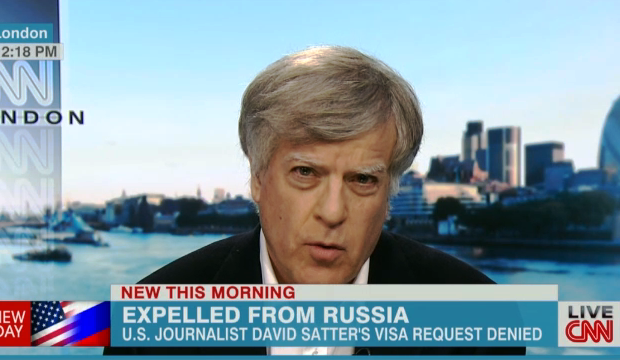

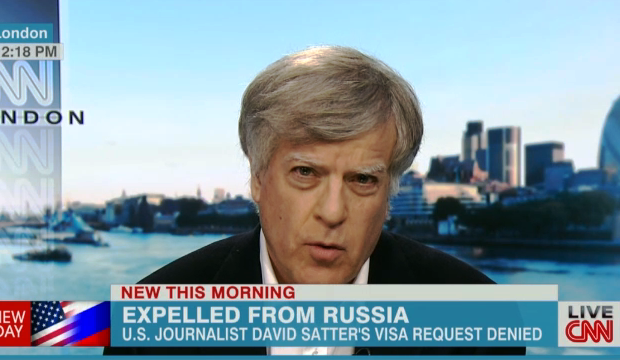

Fielding calls in the back of a London black cab, American journalist David Satter is a busy man.

Satter, who has reported on Soviet and Russian affairs for nearly four decades, was appointed an adviser to US government-funded Radio Liberty in May 2013. In September, he moved to Moscow. But at Christmas, he was informed he was no longer welcome in the country — the first time this has happened to an American reporter since the cold war.

Since Monday night, when the news of his expulsion from Russia broke, he’s been talking pretty much non stop, attempting to explain the manoeuvres which led to him being exiled from his Moscow home.

A statement issued by the Russian foreign ministry claims that Satter had violated Russian law by entering the country on 21 November, but not applying for a visa until 26 November.

Satter dismisses this as “nonsense”, saying he had been assured that a visa that had expired on 21 November would be renewed the following day, with no gap. As it happened, the visa was not renewed on time, “in order to create a pretext”, he tells Index.

To cut a short cut through a labyrinthine tale of bureaucracy: Satter says he left Russia in order to gain a new entry visa, which he could then exchange for a residency visa as an accredited correspondent for Radio Liberty.

He was repeatedly told this visa had been secured. Eventually, on 25 December, he was told that he had a number for a visa, but not the necessary invitation to accompany it. “Kafkaesque”, he calls it. The embassy official had never heard of this happening before. And, as Satter points out, he would not have been issued a number for a new visa in December if it had not been approved.

Eventually, he was told to speak to an official named as Alexei Gruby, who told him that “the competent organs” (code, Satter says, for the FSB) had decided that his presence in Russia was not desirable, language normally reserved for spies. “And now we see I have been barred for five years.”

“The point is, I urge you not to get caught up in their bureaucratic intrigues…the real reason was given to me, in Kiev, on 25 December.”

Is this just another example of FSB muscle flexing?

“Possibly. I’ve known them for a number of years, and I can’t always understand what they’re doing. Usually what they do is not very good…”

This is not Satter’s first brush with the Russian secret services. In a long career with the Financial Times, Radio Liberty and other outlets, he has experience of the KGB and its sucessor. “In 1979, they tried to expel me, accusing me of hooliganism. They once organised a provocation in one of the Baltic republics in which they posed as dissidents. I spent a couple of days with them, thinking I was with dissidents – I was really with the KGB. It’s a long history. It’s in my movie. We showed it in the Maidan [December’s anti-government protests in Ukraine]. Maybe they didn’t like that.”

Satter’s film, the Age of Delirium, is an account of the fall of the Soviet Union.

Is this expulsion a personal thing? Or a move against Radio Liberty? “It’s hard to say whether it’s me, or Radio Liberty, or both.”

Satter is concerned at leaving behind research materials and belongings in Moscow, saying it is likely his son, a London-based journalist, will have to go to Russia to collect them “unless they reverse their decision, which I hope they do”.

In spite of the recent amnesty that saw Pussy Riot’s Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina released from prison, as well as opposition figure Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the diagnosis for free speech in Russia is not good. Alyokhina dismissed her release as a “hoax”, designed to prove Putin’s power. Meanwhile, state broadcaster RIA Novosti has been dissolved and reimagined as “Rossia Segodnya” (“Russia Today” – no coincidence it bears the same name as the notorious English language propaganda station), with many fearing closer Kremlin control.

One Russian journalist I spoke to felt that, ahead of the Sochi games, the expulsion of Satter is a message to all journalists: no matter how experienced, well-known, and well-supported you are, you are still at the mercy of the authorities.

This article was posted on 14 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Jan 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, European Union, Politics and Society

This article is part of a series based on our report, Time to Step Up: The EU and freedom of expression

Collectively, the European Union of 28 member states has an important role to play in the promotion of freedom of expression in the world. Firstly, as the world’s largest economic trading block with 500 million people that accounts for about a quarter of total global economic output, it still has significant economic power. Secondly, it is one of the world’s largest “values block” with a collective commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and perhaps more significantly, the European Convention on Human Rights. The Convention is still one of the leading supranational human rights treaties, with the possibility of enforcement and redress. Finally, Europe accounts for two of the five seats on the UN Security Council (Britain and France), so has a crucial place in the global security framework. The EU itself has limited foreign policy and security powers (although these powers have been enhanced in recent years), leaving significant importance to the foreign policies of the member states. Where the EU acts with a common approach it has leverage to help promote and defend freedom of expression globally.

How the European Union supports freedom of expression abroad

The European Union has a number of instruments and institutions at its disposal to promote freedom of expression in the wider world, including its place as an observer at international fora, its bilateral and regional agreements, the European External Action Service (EEAS) and geographic policies and instruments including the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) and the European Neighbouring and Partnership Instrument (ENPI). The EU places human rights in its trade and aid agreements with third party countries and has over 30 stand-alone human rights dialogues. The EU also provides financial support for freedom of expression through the European Development Fund (EDF), the Development Co-operation Instrument (DCI), the European Instrument for democracy and human rights (EIDHR) and the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The EU now also has a Special Representative for Human Rights. Since 1999, the EU has published an annual report on human rights and democracy in the world. The latest report, adopted in June 2012, contains a special section on freedom of expression, including freedom of expression and “new media”. It recalls the EU’s commitment to “fight for the respect of freedom of expression and to guarantee that pluralism of the media is respected” and emphasises the EU’s support to free expression on the internet.

The European Union has two mechanisms to financially support freedom of expression globally: the European Instrument for democracy and human rights (EIDHR) and the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The latter was specially created after the Arab Spring in order to resolve specific criticism of the EIDHR: that it didn’t support political parties, non-registered NGOs and trade unions and could not react quickly to events on the ground. The EED is funded by, but is autonomous from, the European Commission, with support from member states and Switzerland. The aims of the EED, to provide rapid and flexible funding for pro-democratic activists in authoritarian states and democratic transitions, is potentially a “paradigm shift” according to experts that will have to overcome a number of challenges, in particular a hesitation towards funding political parties and the most active and confrontational of human rights activists. The EU also engages with the UN on human rights issues at the Human Rights Council (HRC) and in the 3rd Committee of the General Assembly. The EU, as an observer along with its member states, is one of the more active defenders of freedom of expression in the HRC. Promoting and protecting freedom of expression was one of the EU’s priorities for the 67th Session of the UN General Assembly (September 2012-2013). The European Union was also instrumental in the adoption of a resolution on the “Safety of Journalists” (drafted by Austria) in September 2012. The European Union is most effective at the HRC where there is a clear consensus among member states within the Union . Where there is not, for instance on the issue of blasphemy laws, the Union has been less effective at promoting freedom of expression.

The EU and its neighbourhood

The EU has had mixed success in promoting freedom of expression in its near neighbourhood. Enlargement has clearly been one of the European Union’s most effective foreign policy tools. Enlargement has had a substantial impact both on the candidate countries’ transition to democracy and respect for human rights. With enlargement slowing, the leverage the EU has on its neighbourhood is under pressure. Alongside enlargement, the EU engages with a number of foreign policy strategies in its neighbourhood, including the Eastern Partnership and the partnership for democracy and shared prosperity with the southern Mediterranean. This section will look at the effectiveness of these policies and where the EU can have influence.

The EU and freedom of expression in its eastern neighbourhood

Europe’s eastern neighbourhood is home to some of the least free places for freedom of expression. The collapse of the former Soviet Union and the enlargement of the European Union has significantly improved human rights in eastern Europe. There is a marked difference between the leverage the European Union has on countries where enlargement is a real prospect and the wider eastern neighbourhood, where it is not, in particular for Russia and Central Asia. In these countries, the EU’s influence is more marginal. Enlargement has clearly had a substantial impact both on the candidate countries’ transition to democracy and their respect for human rights because since the Treaty of Amsterdam, respect for human rights has been a condition of accession to the EU. In 1997, the Copenhagen criteria were outlined in priorities that became “accession partnerships” adopted by the EU and which mapped out the criteria for admission to the EU. They related in particular, to freedom of expression issues that needed to be rectified. With the enlargement process slowing since the “big bang” in 2004, and countries such as Ukraine and Moldova having no realistic prospect of membership regardless of their human rights record, the influence of the EU is waning in the wider eastern neighbourhood.

After enlargement, the Eastern Partnership is the primary foreign policy tool of the European Union in this region. Launched in 2009, the initiative derives from the EU’s Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which is specific about the importance of democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights. In this region, the partnership covers Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Freedom of expression has been raised consistently during human rights dialogues with these six states and in the accompanying Civil Society Forum. The Civil Society Forum has also been useful in helping to coordinate the EU’s efforts in supporting civil society in this region. Although it has never been the main aim of the Eastern Partnership to promote freedom of expression, it has had variable success in promoting this right with concrete but limited achievements in Belarus, the Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova; with a more ineffectual role being seen in Azerbaijan.

In recent years, since the increased input of the EEAS in the ENP, the policy has become more markedly political, with a greater emphasis on democratisation and human rights including freedom of expression after a slow start. In particular, freedom of expression was raised as a focus for the ENP after its review in 2010-2011. This is a welcome development, in marked contrast to the technical reports of previous years. This also echoes the increased political pressure from member states that have been more public in their condemnation of human rights violations, in particular regarding Belarus. Belarus is one Eastern Partnership country where the EU has exerted a limited amount of influence. The EU enhanced its pressure on the country after the post-presidential election clampdown beginning in December 2010, employing targeted sanctions and increasing support to civil society. This has arguably helped secure the release of some of the political prisoners the regime detained. Yet the lack of a strong sense of strategy and unity within the Union has hampered this new pressure to deliver more concrete results. Likewise, the EU’s position on Ukraine has been set back by internal divisions, even though the EU’s negotiations on the Association Agreement included specific reference to freedom of expression.

In Azerbaijan, the EU’s strategic oil and gas interests have blunted criticism of the country’s poor freedom of expression record. Azerbaijan holds over 89 political prisoners, significantly more than in Belarus, yet the EU’s institutions, individual member states and European politicians have failed to be vocal about these detentions, or other freedom of expression violations. In the EU’s wider neighbourhood outside the Eastern Partnership, the EU has taken a less strategic approach and accordingly has been less successful in either raising freedom of expression violations or helping to prevent them.

The European Union’s relationship with Russia has not been coherent on freedom of expression violations. While the institutions of the EU have criticised specific freedom of expression violations, such as the Pussy Riot sentencing, they were slow to criticise more sustained attacks on free speech such as the clampdown on civil society and the inspections of NGOs using the new Foreign Agents Law. The progress report of EU-Russia Dialogue for Modernisation fails to mention any specific freedom of expression violations in Russia. The EU has also limited its financial involvement in supporting freedom of expression in Russia, unlike in other post-Soviet states. The EU is not united on this criticism: individual European Union member states such as Sweden and the UK are more sustained in their criticisms of Russia’s free speech violations, whereas other member states such as Germany tend to be less critical. It is argued that Russia’s powerful economic interests have facilitated a significant lobbying operation including former politicians that works to reduce criticism of Russia’s freedom of expression violations.

In this region, the European Union’s protection of freedom of expression is weakest in Central Asia. While the EU has human rights dialogues with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, it has not acted strategically to protect freedom of expression in these countries. The EU dramatically reduced its leverage in Uzbekistan in 2009 by relaxing arms sanctions with little in return from the Uzbek authorities, who continue to fail to abide by international human rights standards. Arbitrary arrests, beatings and torture at the hands of the security services, as well as unfair trials of the regime’s critics are all commonplace. The European Parliament’s special rapporteur report of November 2012, took a tough stance on human rights in Kazakhstan, making partnership conditional on respect for Article 10 rights. But, this was undermined by High Representative Baroness Ashton’s visit to the country in November 2012, where she failed to raise human rights violations at all.

This lack of willingness to broach freedom of expression issues continued during Baroness Ashton’s first official visit to four of the five Central Asian republics: Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kazakhstan. In Kyrgyzstan she additionally attended an EU-Central Asia ministerial meeting, where the Turkmen government (one of the top five most restrictive countries in the world for freedom of expression) was represented. Baroness Ashton’s lack of vocal support for human rights was condemned by local NGOs and international watchdogs.