20 Sep 2013 | Africa, News, Uganda

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

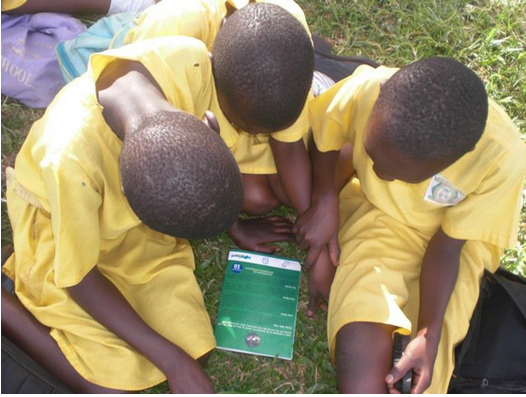

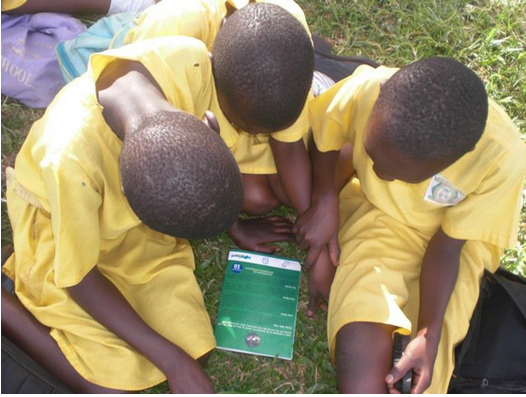

It could be a true story. In Uganda there are an estimated 2.75 million children engaged in work, although not many of those will have the happy ending. But The Little Maid is a work of fiction, written by Oscar Ranzo, a Ugandan social worker turned author who has penned five children’s books. Now, The Little Maid is being distributed to schools across the country low-cost (5,000 Ugandan shillings or $1.90 each) through his Oasis Book Project. The project aims to improve the reading and writing culture in Uganda and provide school-children with entertaining but educational stories to which they can relate. Ranzo sells most of his books to schools, with the proceeds used to publish more titles. However, he also donates copies to more impoverished areas.

In 1969, Professor Taban Lo Liyong, one of Africa’s best-known poets and fiction writers, declared Uganda a ‘literary desert’. “What we want to do with this project is create an oasis in the desert,” explains Ranzo. “That’s why I called it the Oasis Book Project.”

The small print

Excluding textbooks, there are only about 20 books published in Uganda annually. According to a study last year by Uwezo, an initiative aimed at improving competencies in literacy and numeracy among children aged six to sixteen years in East Africa, more than two out of every three pupils who had finished two years of primary school failed to pass basic tests in English, Swahili or numeracy. For children in the lower school years, Uganda recorded the worst results.

Growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, Ranzo was privileged to have a grandfather who had a library and attended a private school that held an after class reading session. He was a particularly avid fan of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five series.

“But Mum was a nurse and she wanted me to be a doctor. I wanted to pursue literature and she told me ‘no you can’t do that’, so I did sciences,” says Ranzo, stressing that literature, which remains optional in secondary school, is not taken seriously in Uganda.

Furthermore, many local publishers do not see writing fiction as profitable. “They’d rather publish textbooks and get the government to buy them,” Ranzo explains.

His books are available in two central Kampala bookshops for 8,000 shillings ($3). But in the past 15 months fewer than 20 have moved from the shelves, while he has sold over 3,000 to 20 schools in three districts.

Fiction imitating life

Saving Little Viola, his first book in which the female protagonist, Viola, was introduced, was published in 2011 by NGO Lively Minds. The story ends with Viola being saved by her best friend from two men who want to use her for a ritual sacrifice. UNICEF funded its distribution to 36 primary schools across Uganda as part of a child sacrifice awareness programme.

The primary aim of the Oasis Book Project is to encourage reading, although Ranzo admits he would like people to discuss his stories, which have themes close to his heart. Children being forced into work, the theme of The Little Maid, is something he has witnessed himself.

“Many kids are brought from villages to work as maids in homes in towns or cities, and the treatment they are subjected to is terrible in many cases,” says Ranzo.

His next book, The White Herdsman, which will be released in 2014, deals with the impact of oil production on communities, a timely subject for Ugandans with oil production expected to start in 2016. The book tells the story of a village where water in the well has turned black after an oil spill. A witchdoctor blames the disaster on an albino child.

Ranzo’s stories have been welcomed at Hormisdallen Primary, a private school in Kamwokya, Kampala. English teacher Agnes Kasibante, speaking to Think Africa Press, praises the book’s impact. “It’s actually a big problem in Uganda, most children don’t know how to read. At least those books give them morale to continue loving reading,” she says.

Ranzo has also penned Cross Pollination, a collection of fictional stories for adults about the spread of HIV in a community. According to a recent report, Uganda may not meet its target to increase adult literacy by 50% by 2015.

“I’ve worked in a big multinational company where people have jobs but they can’t write. Reading can help develop this,” says Ranzo, who is currently attending the University of Iowa’s 47th annual International Writing Program (IWP) Fall Residency.

Uganda’s literary comeback

Jennifer Makumbi, 46, a Ugandan doctoral student at Lancaster University, is one of a new generation of Ugandan authors. She won the Kwani Manuscript Project, a new literary prize for unpublished fiction by Africans, for her novel The Kintu Saga. She said Taban Lo Liyong’s description of Uganda as a literary desert was “heartbreaking, especially as in the 1960s Uganda seemed to be poised to be a leading literary producer”.

“But perhaps it is exactly this description that is pushing Ugandans to write in the last ten years,” she continues. “Yes, we have not caught up with West Africa yet but… there are quite a few wins.” In recent years, two female Ugandan authors, Monica Arac de Nyeko and Doreen Baingana, won the Caine Prize for African Writing and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize respectively. Makumbi’s Kwani prize adds her to a list of eminent Ugandan authors.

Makumbi is optimistic about the future of Ugandan literature: “These I believe are indications that Uganda is on its way.”

This article was originally published on 17 Sept 2013 at Think Africa Press and is reposted here by permission.

7 Aug 2013 | In the News

#DONTSPYONME

Tell Europe’s leaders to stop mass surveillance #dontspyonme

Index on Censorship launches a petition calling on European Union Heads of Government to stop the US, UK and other governments from carrying out mass surveillance. We want to use public pressure to ensure Europe’s leaders put on the record their opposition to mass surveillance. They must place this issue firmly on the agenda for the next European Council Summit in October so action can be taken to stop this attack on the basic human right of free speech and privacy.

(Index on Censorship)

GLOBAL

Google revamps search to feature in-depth articles

Want to know more about censorship, love, or legos? The Web giant reworks its search feature to display more comprehensive articles, papers, and blog posts alongside its quick answer listings.

(CNET)

Bitcoin is crucial for the future of free speech, say experts

When US servicemen Bradley Manning was found guilty on 20 counts in connection with leaking classified military information, experts mused that bitcoin was instrumental in the continuing operation of WikiLeaks, the whistleblowing website that he helped.

(Coin Desk)

From the U.K. to Vietnam, Internet censorship on the rise globally

In the U.K., a proposed filter would automatically block pornography and, according to Internet rights groups, other unwanted content. In Jordan, newsWeb sites can’t operate without a special license from the government.

(Washington Post)

RUSSIA

Welcome to my world: An open letter to Edward Snowden

Roman Dobrokhotov has some words of wisdom for Russia’s newest resident, Edward Snowden. Translated by John Crowfoot.

(Index on Censorship)

Russia opens probe into flag desecration by US band

Russia’s interior ministry on Monday launched a criminal probe into flag desecration after a US rock musician stuffed a Russian flag down his trousers at a concert.

(Dawn)

SOUTH AFRICA

Free speech for all, save the chief justice?

CHIEF Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng may face an impeachment hearing before the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) for comments he made last month at the annual general meeting of Advocates for Transformation.

(Business Day Live)

TANZANIA

Report: Anti-media attacks in Tanzania on rise, repressive laws sowing fear, self-censorship

A media watchdog says that a rise in anti-press attacks and repressive laws is sowing fear and self-censorship among journalists in Tanzania.

(Washington Post)

TURKEY

Former head of Turkish army is one of 17 jailed for life over ‘Deep State’ coup plot

Ringleaders of ‘deep state’ plot are sentenced as epic trial concludes with 300 verdicts

(The Independent)

UNITED KINGDOM

Guardian rejects press watchdog as ‘own goal’ threatening independence

New regulator will lack support of press intrusion victims and allow dominance by biggest papers, says CEO Andrew Miller

(The Guardian)

Dear Mr. Cameron: U.K.’s Love for Porn and Censorship Don’t Mix

There’s an insatiable demand for Internet porn in the U.K. Whether it be straight, gay, tranny or BDSM, modern Brits have put their arms around the idea of devouring sexually explicit material in the privacy of their own homes.

(XBIZ)

UNITED STATES

Bringing global human rights into the surveillance debate

Guest Post: Surveillance is no longer the Cold War mentality of “us” and “them”

(Index on Censorship)

The Judd Apatow Test of Free Speech

The issue was whether a school district in Pennsylvania violated the rights of two middle-school girls who were suspended for wearing “I ♥ boobies!” bracelets.

(Wall Street Journal)

‘Virgin Mary Should’ve Aborted’: Facebook Page Is Not Anti-Christian Hate Speech, Says Social Network

Another rabble-rousing community page is testing the limits of Facebook’s policies regarding offensive content, only this time it’s the devoutly religious who say they are the target of hate speech.

(International Business Times)

‘CENSORSHIP’: ANTI-ABORTION ACTIVISTS PREPARE TO BATTLE THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA

Pro-life groups have had enough of what they call a “media blackout” when it comes to the abortion issue. So, they’re coming together to hold a “March on the Media” this Thursday. The protest rally is being organized by Lila Rose, president of Live Action, an anti-abortion group. The event’s targets are mainstream media outlets that some critics, including Rose, believe have been too silent about issues pertaining to life and the protection of the unborn.

(The Blaze)

Sen. Rockefeller Continues His Quest To Regulate Free Speech With His ‘Violent Content Research Act’

Sen. Jay Rockefeller’s pet project — fighting violent media — just got a shot in the arm from the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee (because those three seem like perfect complements…), which “advanced” his legislation directing the National Academy of Sciences to study the effects of violent media on children.

(Tech Dirt)

It’s Dangerous For Free Speech When We Confuse Leakers With Spies

We’ve tried to make similar points a few times in the past about our concern with the Obama administration going after whistleblowers and the journalists who publish their leaks by using the Espionage Act more than all other Presidents in history, combined (more than twice as much, actually).

(Tech Dirt)

VIETNAM

US Concerned About Vietnam Censorship Law

The United States is criticizing a new decree in Vietnam that would outlaw sharing news stories online.

(VOA)

Previous Free Expression in the News posts

Aug 6 | Aug 5 | Aug 2 | Aug 1 | July 31 | July 30 | July 29 | July 26 | July 25 | July 24 | July 23 | July 22 | July 19 | July 18 | July 17 | July 16

21 Jun 2013 | In the News

INDEX POLICY PAPER

Is the EU heading in the right direction on digital freedom?

While in principle the EU supports freedom of expression, it has often put more emphasis on digital competitiveness and has been slow to prioritise and protect digital freedom, Brian Pellot, digital policy advisor at Index on Censorship writes in this policy paper

(Index on Censorship)

BAHRAIN

HRW: ‘No Space for Political Dissent’ in Bahrain

New laws and lengthy jail terms for activists have put freedom of association in Bahrain under severe threat, according to a report from Human Rights Watch.

(VOA)

BANGLADESH

Facebook and freedom of speech

The parliament of Bangladesh on June 11 passed the Anti-Terrorism (Amendment) Bill 2013 which will allow the courts to accept videos, still photographs and audio clips used in Facebook, Twitter, Skype, and other social media for trial cases.

(Dhaka Tribune)

BORNEO

Film industry players told to instil patriotism, cultural values

Film industry players have been urged to instil the values of patriotism and culture in their products to educate society.

Deputy Home Minister Datuk Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar said this was in order to change the perception of society towards the values of culture and nationhood.

(The Borneo Post)

BRAZIL

Brazil’s president meets protests with an anti-Erdogan response

Protests have popped up across the globe in recent years, but government response has varied. Rousseff’s approach contrasted with the adversarial position of Turkey’s Erdogan, for example.

(Christian Science Monitor)

CANADA

BC Supreme Court rejects Zesty’s comedian appeal

The BC Supreme Court has upheld a decision by the BC Human Rights Tribunal which found that Lorna Pardy’s complaint against comedian Guy Earle and the owners of Zesty’s restaurant was justified.

(Xtra!)

EUROPE

Media: freedom has declined in West Balkans, Turkey

Freedom of the media has declined in the past two years in the Balkans and in Turkey, OSCE Representative Dunja Mijatovic said at the EU ”Speak Up!” conference on Freedom of Expression here today.

(Ansa Med)

GHANA

Defamation against FCT Minister: Kaduna-based Publisher Risks N5b Libel Suit

FCT Minister, Senator Bala Mohammed has served notice of his intention to slam a Five Billion Naira (N5,000,000,000:00) on the Kaduna based Desert Herald newspaper and its publisher, Alhaji Tukur Mamu for defamation and libel following series of damaging publications against him by Mamu through his newspaper and two others. Similarly, the Director of Treasury of FCT Administration, Alhaji Ibrahim Bomai through the same solicitors has threatened to institute a Two Billion Naira (N2,000,000,000:00) against Mamu for the same offence of defamation and libel.

(Spy Ghana)

IRELAND

“The ferociousness of the censorship made Ireland a laughing stock”

Diarmaid Ferriter discusses the widespread censorship of publications in Ireland during the 20th century

(NewsTalk 106-108FM)

LIBYA

Blasphemy Charges Over Election Posters – Political Party Officials Could Face Death Penalty

Libyan judicial authorities should immediately drop all criminal charges that violate freedom of speech over election poster cartoons against two Libyan National Party officials. Under the laws being applied in this case, the men could face the death penalty over posters their party displayed during the 2012 election campaign for the General National Congress.

(All Africa)

MEXICO

Will Mexico’s plans for reducing violence mean anything for journalists?

Mexico’s president, Enrique Peña Nieto, promised that tackling crime and drug-related violence is a priority for his six-month-old government. While improving safety is important, Peña Nieto must also remember that protecting journalists and human rights workers must go beyond words, says Sara Yasin

(Index on Censorship)

TANZANIA

Zanzibar Legislators Call for National Unity Govt Self-Censorship

A LEGISLATOR of the Zanzibar House of Representatives, Mr Omar Ali Shehe (CUF), has said Zanzibaris were unhappy with the performance of the Government of National Unity (GNU), formed jointly between Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and CUF two-and-half years ago.

(All Africa)

TUNISIA

How Tunisia is Turning Into a Salafist Battleground

An interview with a professor who was attacked for standing up for secularism.

(The Atlantic)

TURKEY

Şanar Yurdatapan on Turkey: ‘Things will never be the same again’

In Phnom Penh, Cambodia, for the IFEX General Meeting and Strategy Conference 2013, Index Director of Campaigns and Policy Marek Marczynski spoke with 2002 Index on Censorship award winner Şanar Yurdatapan, a composer and song writer who campaigns against the prosecution of publishers by the Turkish authorities. Yurdatapan shared his views on the events sweeping Turkey

(Index on Censorship)

UNITED KINGDOM

The end of Britain’s social media prosecutions?

Keir Starmer’s new guidelines aim to minimise controversial criminal cases against Twitter and Facebook users. But will they work, asks Padraig Reidy

(Index on Censorship)

Psychic wins libel case over claim she duped Dublin audience

The publisher of the Daily Mail has agreed to pay “substantial” damages to a psychic after an article suggested she had “perpetrated a scam” on a Dublin theatre audience.

(Irish Times)

Government to propose new free speech clause for marriage supporters

Government ministers are expected to announce new proposals to offer more protection in law for those who express the view that marriage can only be between one man and one woman.

(Christian Concern)

UNITED STATES

Supreme Court upholds free speech for groups fighting AIDS

The Supreme Court rejects a federal law that requires organizations to announce anti-prostitution policies in order to receive funding.

(Los Angeles Times)

L. Brent Bozell III: Media coverage shows ‘anti-gay’ view censorship

The media elites have never been less interested in objectivity than they are right now on “gay marriage.” They don’t wear rainbow flags on their lapels when they appear on television, but the coverage speaks for itself.

(NVDaily)

Student wins free-speech lawsuit against teacher

A Michigan teacher who kicked a student out of class after the teen made a comment against homosexuality during a high school anti-bullying day was ordered to pay $1 for violating his free speech rights.

(Associated Press via SFGate.com)

No Sympathy For Media Just Now Realizing Obama ‘A Serious Threat’ To Free Speech

On Thursday, conservative columnist Michelle Malkin joined Fox & Friends host Steve Doocy where she dug into the ongoing scandals and controversies that have engulfed President Barack Obama’s administration. Malkin noted that some in the media who had previously supported the president are now more leery of the administration.

(Mediaite)

Fair Trade Music Project Speaks Out for Silenced Songwriters

Following the success of the World Creators Summit held in Washington, DC, June 4-5, the Music Creators North America (spearheading the Fair Trade Music Project) took another step toward defending the rights of creators.

(Herald Online)

Planned Parenthood says Kansas abortion law violates doctors’ free speech rights

Planned Parenthood filed a lawsuit Thursday over a new Kansas law requiring doctors to inform women seeking abortions that they’re ending the life of a “whole, separate, unique, living human being.”

(The Washington Post)

UCF Professor Accused of ‘Hate Speech Toward Islam’

The Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) has filed a complaint against a University of Central Florida (UCF) professor, who they claim is teaching that Muslims are taught to hate “from the cradle.” According to The Raw Story, CAIR referenced a seminar held by Professor Jonathan Matusitz in January, which included “inaccurate information, anti-Muslim bigotry and hostility in the form of hate speech toward Islam and Muslims.”

(Ring of Fire)

EU-US trade talks won’t exclude film, culture: US envoy

The US ambassador to the European Union insisted Thursday that Europe’s film and cultural industry will not be totally excluded from upcoming talks on striking the world’s biggest free trade deal.

(AFP)

VIETNAM

Access submits UPR report on Vietnam: Cyber attacks on civil society a key concern

Access has partnered with ARTICLE 19, PEN International, and English PEN on a joint submission on Vietnam to the United Nations Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The submission focuses on the lack of improvement of human rights, specifically freedom of expression, in Vietnam since the last UPR in 2009, and highlights the Vietnamese government’s troubling response to the recent increase in cyber attacks against civil society.

(Access)

Previous Free Expression in the News posts

June 20 | June 19 | June 18 | June 17 | June 14 | June 13 | June 12

9 Oct 2012 | Azerbaijan Statements, Campaigns

The following letter calling for greater defamation law reform, including limiting corporations ability to use libel law to silence civil society critics, was coordinated by Index on Censorship and the International Freedom of Expression Exchange network (IFEX)

(more…)

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.

The heroine of The Little Maid, Viola, is an eight-year-old Ugandan girl who lives with her destitute grandmother and dreams of going to school. Instead, she is sent to live with her aunt, who promises to pay her school fees if Viola works for her first. Viola becomes a maid, forced to wash clothes, scrub the bathroom, cook and live in servants’ quarters. But every day when her cousins’ tutor arrives, she crawls underneath the dining room table to eavesdrop on the lessons. Eventually Viola learns to read and write and escapes the clutches of her evil aunt, who is found guilty of child abuse and child slavery and ordered to school her niece.