17 Sep 2020 | Volume 49.03 Autumn 2020, Volume 49.03 Autumn 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”The brave stand up when others are afraid to do so. Let’s remember how hard that is to do, says Rachael Jolley in the autumn 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.”][vc_column_text]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

The US Supreme Court justice may be a popular icon right now, but when she set her course to be a lawyer she was in a definite minority.

For many years she was the only woman on the court bench, and she was prepared to be a solitary voice when she felt it was vital to do so, and others strongly disagreed.

The dissenting voice and its place in US law is a fascinating subject. A justice on the court who disagrees with the majority verdict publishes a view about why the decision is incorrect. Sometimes, over decades, it becomes clear that the individual who didn’t go with the crowd was right.

The dissenting voice, it seems, can be wise beyond the established norms. By setting out a dissenting opinion, it gives posterity the chance to reassess, and perhaps to use those arguments to redraft the law in later times.

Bader Ginsburg was the dissenting voice in the case of Ledbetter v Goodyear – in which Lily Ledbetter brought a case on pay discrimination but the court ruled against her – and in Shelby County v Holder on voting discrimination, an issue likely to be hotly debated again in this year’s US presidential election. Bader Ginsburg’s opinions may not have been in the majority when those cases were heard but the passage of time, and of some legislation, proved her right.

The dissenting voice in law is a model for why freedom of expression is so vital in life. You may feel alone in your fight for the right to change something (or in your position on why something is wrong), but you must have the right to express that opinion. And others must be willing to accept that minority views should be heard – even if they disagree with them.

Fight for the principle, and when the time comes that you, your friends or your neighbours need it, it will be there for you.

Right now, writers, artists and activists are standing up for that principle, not necessarily for themselves but because they feel it is right.

Sometimes they also bravely dissent when most people are afraid to speak up for change, or to disagree with those who shout the loudest.

Being different and on the outside is a lonely place to be, but the pressure is even greater when you know opposing an idea, or law, could mean losing your home or your job, or even landing in prison.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd0d0d”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The dissenting voice in law is a model for why freedom of expression is so vital in life.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

As editor-in-chief at Index I have been privileged to work with extraordinary people who are willing to be dissenting voices when, all around them, society suggests they should be quiet. They smuggle out words because they think words make a difference. They choose to publish journalism and challenging fiction because they want the world to know what is going on in their countries. They often take enormous risks to do this.

For them, freedom of expression is essential. Murad Subay is a softly spoken Yemeni artist with a passion for pizza. He produced street art even as the bombs fell around him in Sana’a. Often called Yemen’s Banksy, Subay – an Index award winner – worked under unbelievably horrible conditions to create art with a message.

In an interview with Index in 2017, Subay told us: “It’s very harsh to see people every day looking for anything to eat from garbage, waiting along with children in rows to get water from the public containers in the streets, or the ever-increasing number of beggars in the streets. They are exhausted, as if it’s not enough that they had to go through all of the ugliness brought upon them by the war.”

Dissenting voices come from all directions and from all around the world.

From the incredibly strong Zaheena Rasheed, former editor of the Maldives Independent, who was forced to leave her country because of death threats, to regular correspondence from our contributing editor in Turkey, Kaya Genç, these are journalists who keep going against the odds. These are the dissenting voices who stand with Bader Ginsburg.

Over the years, the magazine has featured many writers who have stood up against the crowd. People such as Ahmet Altan, whose words were smuggled out of prison to us. He told us: “Tell readers that their existence gives thousands of people in prison like me the strength to go on.”

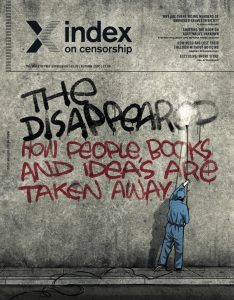

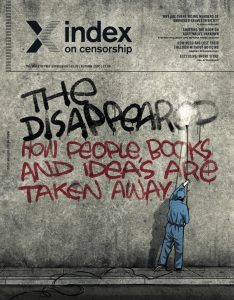

In this issue, we explore those whose ideas and voices – and sometimes, horrifically, bodies – are deliberately disappeared to muffle their dissent, or even their very existence.

Many people associate the term “the disappeared” with Argentina during the dictatorships, where we know about some of the horrific tactics used by the junta. Opposition figures were killed; newborn babies were taken from their mothers and given to couples who supported the government, their mothers murdered and, in many cases, dumped at sea to get rid of the evidence. The grandmothers of those who were disappeared are still fighting to bring attention to those cases, to uncover what happened and to try to trace their grandchildren using DNA tests.

Index published some of those stories from Argentina at the time because Andrew Graham-Yooll, who was later to become the editor at Index, smuggled out some of the information to us and to The Daily Telegraph, risking his life to do so.

We explore what and who are being disappeared by authorities that don’t want to acknowledge their existence.

Thousands of people who are escaping war and starvation try to flee across the Mediterranean Sea: hundreds disappear there. Their bodies may never be found.

It is convenient for the authorities on both sides of the sea that the numbers appear lower than they really are and the real stories don’t get out.

In a special report for this issue, Alessio Perrone reveals the tactics being used to cover up the numbers and make it appear there are fewer journeys and deaths than in reality.

The International Organisation for Migration’s Missing Migrants Project says that 20,000 people have died in the Mediterranean since records began in 2014, but many say this is an underestimation.

Certainly there are unmarked graves in Sicily where bodies have been recovered but no one knows their names (see page 30). The Italian government has, as we have previously reported, used deliberate tactics to make it harder to report on the situation and to stop the rescue boats finding refugees adrift near her boundaries.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#2a31b7″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”It is convenient for the authorities on both sides of the sea that the numbers appear lower than they really are and the real stories don’t get out.”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Also in this issue, Stefano Pozzebon and Morena Joachín report on how Guatemala’s national police archives – which house information on those people who were disappeared during the civil war – is currently closed, and not for Covid-19 reasons (see page 27).

Fifteen years after the archive was first opened to the public, a combination of political pressure and a desire to rewrite history in the troubled nation has closed it. This is a tragedy for families still using it in an attempt to trace what happened to their families.

In Azerbaijan (see page 8), another tactic is being used to silence people – this time using technology. Activists are having their profiles hacked on social media and then posts and messages are being written by the hackers and posted under their names.

Their real identities conveniently disappear under a welter of false information – a tactic used to undermine trust in journalists and activists who dare to challenge the government so that the public might stop believing what they write or say.

This is my 30th and final issue of the magazine after seven years as editor (although I will still be a contributing editor), and it is another gripping one.

They smuggle out words because they think words make a difference.

Over the years, I am proud to have worked with the incredible, brave, talented and determined. We have published new writing by Ian Rankin, Ariel Dorfman, Xinran, Lucien Bourjeily, and Amartya Sen, among others. And it has been a privilege to work with the mindblowing, sharp, analytical journalism from the pens of our incredible contributing editors over the years, including Kaya Genç, Irene Caselli, Natasha Joseph, Laura Silvia Battaglia, Stephen Woodman, Duncan Tucker and Jan Fox, plus regular contributors Wana Udobang, Karoline Kan, Steven Borowiec, Alessio Perrone and Andrey Arkhangelsky.

These people do amazing work: their writing is ahead of the game and they bring together thought-provoking analysis and great human stories. Thank you to all of them, and to deputy editor Jemimah Steinfeld.

They have told me again and again why they value writing for Index on Censorship and the importance of its work.

And because we believe that supporting writers and journalists is also about them getting paid for their work, unlike some others we have always supported the principle of paying people for their journalism.

Over the years we have attempted to go above and beyond, providing a little extra training when we can, translating Index articles into other languages, inviting journalists we work with to events, and introducing them to book publishers.

But just like the first time I ventured into the archives of the magazine, I am still amazed by what gems we have inside. We have recently reached our biggest readership to date, with hundreds of thousands of articles being downloaded in full, showing an appetite for the kind of journalism and exclusive fiction we publish.

Thank you, readers, for being part of the journey, and please continue to support this small but important magazine as it continues to speak for freedom.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the former editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship’s autumn 2020 issue, entitled The disappeared: how people, books and ideas are taken away.

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2020 magazine podcast featuring Hong Kong-based journalist Oliver Farry, who discusses the crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrations in the region

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2020 | Volume 49.02 Summer 2020, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Why don’t we learn that censorship and lack of trust in society puts us all at risk, particularly in times of crisis, asks Rachael Jolley in the summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine”][vc_column_text]

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

Censorship by the Chinese state that stopped the rest of the world finding out what was happening as early as it could have.

Surely this is one of the most compelling arguments against censorship that we have seen in our lifetimes. Showing that if we know about a risk, we are able to discuss, to explore, to research, to prepare, and to take measures to avoid it.

As Covid-19 spread through the world, the parallels with World War I and the Spanish Flu were obvious. Here was a dangerous disease that many countries refused to acknowledge, that doctors were prevented from speaking about and that, for a time, the public had no knowledge of.

In 2014, I asked leading public health professor Alan Maryon-Davis to write about World War I and the flu epidemic for this magazine, a lesson from history for today. He wrote: “We also know that it was the deadliest affliction ever visited upon humanity, killing at least 50 million people world- wide, probably nearer 100 million, several times more than [the] 15-20 million killed by the war itself – and more in a single year than the Black Death killed in a century.”

Maryon-Davis identified three weak links that could have incredibly dangerous consequences in the reaction to a pandemic.

One was that health workers on early cases might worry about reporting it (self- censorship); the second was that governments would worry about political/cultural consequences (political censorship); and the third was that a cloak of secrecy might be thrown over it (pure censorship). Check, check, check. It’s happened again.

Lessons learned from history? Practically nil.

As we move through the tracking phase of this pandemic, we need to recognise that public trust is an essential part of any response, and that public will comes from a belief in society – and a belief that it will act for the public good. Trust also comes from a belief that your government will not collect private information about you and use it without permission, or to your detriment.

Historically, those who fought for freedom of expression and speech also fought for the right to privacy: your right to keep information private – such as your religion or sexual orientation – and the right for you not to have an illegal search of your private papers or your home. Those rights came together in the US constitution because those who wrote it knew what it was like to be in a minority or a protester in a country which oppressed those who did not conform.

They fled those countries to find more freedom, and they sought to create legislation that would mean others could choose to be different, or to express offensive or difficult ideas. That might sound ridiculously ideal- istic, and of course it was – there are plenty of holes people can pick in the reality of US society – but those ideas are strong, and valid for today.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” color=”custom” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”In Turkey there are independent thinkers who believed that home was the last refuge where they could criticise the government”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The right to privacy (and with it the right to express a minority opinion) is often endangered by legislation that is introduced without due process during times of war or crisis.

And it is against this backdrop that activists, journalists, academics and others began to worry that during this pandemic we are, with- out really considering the consequences, giving away our privacy.

Governments around the world have often responded to the Covid-19 situation with diktats that remove an element of democratic governance, or threaten hard-fought-for freedoms, with very little opportunity for public debate.

India’s Justice H.R. Khanna, among others, famously warned that governments use a crisis to ignore the rule of law. “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

This feels like wisdom that’s fitting for the current fractured moment.

In Turkey, there are independent thinkers who believed that home was the last refuge where they could criticise the government or talk about a difference of opinion from the mainstream. The introduction of the Life Fits Home app could mean a severe erosion of that private space, as once they have input their ID numbers, the government will know exactly who is where, and with whom.

As Kaya Genç outlines in his article on p50, the question is: can they trust an autocratic state which could save their lives via contact-tracing not to come after them later for political reasons?

This is similar to the question being asked in Hong Kong by those who protest against the ongoing erosion of the freedom which ensured it was a very different place to live from China in the last two decades.

During the pandemic, there have been discussions about the dangers of sharing personal information with the government, and one Hong Kong citizen we interviewed for this issue outlined why.

“Of course, we’re willing to do what we can as a collective to stop the spread of Covid-19,” she said. “But the point is, we have no trust in the government now. That’s why I don’t want to trade my information with the government in return for a few face masks.”

Another said people were worried about an app that they were required to download if they left the city and wanted to return, asking: “Who knows what they’ll do with our data?”

Some governments have put in place legal checks and balances to give people more confidence, and to offer assurances that data will not be used for other means.

In South Korea, a law was amended after the 2015 Mers outbreak to give authorities extensive powers to demand phone location data, police CCTV footage and the records of corporations and individuals to trace contacts and track infections.

As Timandra Harkness outlines on p11, that same law specifies that “no information shall be used for any purpose other than conducting tasks related to infectious diseases under this act, and all the information shall be destroyed without delay when the relevant tasks are completed”.

In Australia, legislation restricts who may access data gathered by a Covid-19 app, how it may be used and how long it may be kept.

Other countries have done much less to offer legitimacy and transparency to the data- gathering processes in which they are asking the public to participate.

In the UK, for instance, there has been no sign of legislation outlining any restrictions on how data captured by its track and trace system, or expected Covid-19 app, will be restricted from other use, or even stopped from being sold on to third parties.

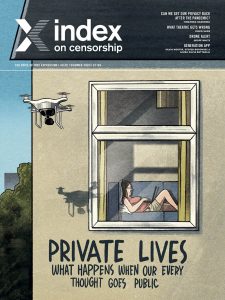

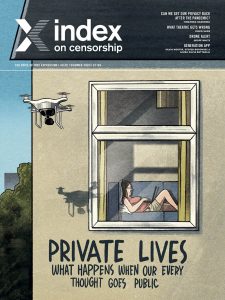

Requests to ask the public to add apps such as these come at the same time as we see rising numbers of drones being used to invade our private spaces, and potentially to track our movements or actions.

We also see a dramatic, mostly unregulated, increase in the use of facial recognition around the world, again taking a hammer to our rights to privacy, and ramping up surveillance.

US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote in the 1920s of those who wrote the early laws of his land: “They knew that order cannot be secured merely through fear of punishment for its infraction; that it is hazardous to discourage thought, hope and imagination; that fear breeds repression; that repression breeds hate; that hate menaces stable government; that the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies, and that the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

Those who fear their privacy is under threat, and who worry about other consequences of being tracked and traced, are unlikely to feel confident in a society that takes away basic freedoms during times of crisis and does not put dramatic changes into place via a parliamentary process. Governments should take note that this threatens pathways to safety.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on macho male leaders

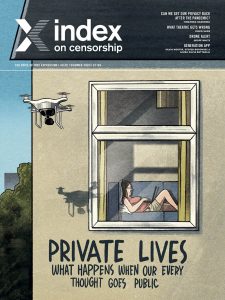

Index on Censorship’s summer 2020 issue is entitled Private Lives: What happens when our every thought goes public

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]The summer 2020 magazine podcast featuring the world premiere of a lockdown playlet written and acted out exclusively for Index on Censorship by Katherine Parkinson

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

17 Jun 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Katherine Parkinson, David Hare, Marina Lalovic, Geoff White and Timandra Harkness”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

In our In Focus section, we interview journalists in Serbia, Hungary and Kashmir who are trying to report the truth in places where the truth can be as dangerous, if not more, than Covid-19. And we have an interview with and poet from the playwright David Hare.

We have a very special culture section in this issue. Three playwrights have written short plays for the magazine around the theme of pandemics. V (formerly Eve Ensler), the author of The Vagina Monologues, takes you to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster; Katherine Parkinson of The IT Crowd writes about online dating during quarantine; Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily is inspired by recent events in his country in his chilling look at protest right now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][vc_column_text]

Back-up plan by Timandra Harkness: Don’t blindly give away more freedoms than you sign up for in the name of tackling the epidemic. They’re hard to reclaim

The eyes of the storm by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Spies are on the streets of Uganda making sure everyone abides by Covid-19 rules. They’re spying on political opposition too. A dispatch from Kampala

Zooming in on privacy concerns by Adam Aiken: Video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think

Seeing what’s around the corner by Richard Wingfield: Facial recognition technology may be used to create immunity “passports” and other ways of tracking our health status. Are we watching?

Don’t just drone on by Geoff White: If drones are being used to spy on people breaking quarantine rules, what else could they be used for? We investigate

Sending a red signal by Tianyu M Fang: When a contact tracing app went wrong a journalist was forced to stay in their home in China

The not so secret garden by Tom Hodgkinson: Better think twice before bathing naked in the backyard. It’s not just your neighbours that might be watching you. Where next for privacy?

Hackers paradise by Stephen Woodman: Hackers across Latin America are taking advantage of the current crisis to access people’s personal data. If not protected it could spell disaster

Italy’s bad internet connection by Alessio Perrone: Italians have one of the lowest levels of digital skills in Europe and are struggling to understand implications of the new pandemic world

Less than social media by Stefano Pozzebon: El Salvador’s new leader takes a leaf out of the Trump playbook to use Twitter to crush freedoms

Nowhere left to hide by Kaya Genç: Privacy has been eroded in Turkey for many years now. People fear that tackling Covid-19 might take away their last private free space

Open book? by Somak Ghoshal: In India, where people are forced to download a tracking app to get paid, journalists are worried about it also being used to access their contacts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Knife-edge politics by Marina Lalovic: An interview with Serbian journalist Ana Lalic, who forced the Serbian government to do a U-Turn

Stage right (and wrong) by Jemimah Steinfeld: The playwright David Hare talks to Index about a very 21st century form of censorship on the stage. Plus a poem of Hare’s published for the first time

Inside story: Hungary’s media silence by Viktória Serdült: What’s it like working as a journalist under the new rules introduced by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán? How hard is it to report?

Life under lockdown: A Kashmiri Journalist by Bilal Hussain: A Kashmiri journalist speaks about the difficulties – personal and professional – of living in the state with an internet shutdown during lockdown

The truth will out by John Lloyd: Journalists need to challenge themselves and fight for media freedoms that are being eroded by autocrats and tech companies

Extremists use virus to curb opposition by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Covid-19 is being used by religious militia as a recruitment tool in Yemen and Iraq. Speaking out as a secular voice is even more challenging

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Masking the truth by V: The writer of The Vagina Monologues (formerly known as Eve Ensler) speaks to Index about attacks on the truth. Plus a new version of her play about living in a nuclear wasteland

Time out by Katherine Parkinson: The star of The IT Crowd discusses online dating and introduces her new play, written for Index, that looks at love and deception online

Life in action by Lucien Bourjeily: The Lebanese director talks to Index about how police brutality has increased in his country and how that informed the story of his new play, published here for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]

Putting abuse on the map by Orna Herr: The coronavirus crisis has seen a huge rise in media attacks. Index has launched a map to track these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Forced out of the closet by Jemimah Steinfeld: As people live out more of their lives online right now, our report highlights how LGBTQ dating apps can put people’s lives at risk

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Mar 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Ak Welsapar, Julian Baggini, Alison Flood, Jean-Paul Marthoz and Victoria Pavlova”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

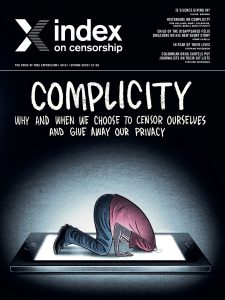

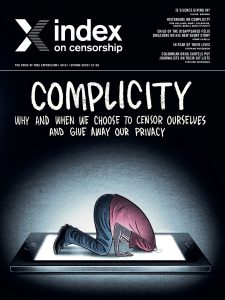

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

In our In Focus section, we sit down with different generations of people from Turkey and China and discuss with them what they can and cannot talk about today compared to the past. We also look at how as world demand for cocaine grows, journalists in Colombia are increasingly under threat. Finally, is internet browsing biased against LBGTQ stories? A special Index investigation.

Our culture section contains an exclusive short story from Libyan writer Najwa Bin Shatwan about an author changing her story to people please, as well as stories from Argentina and Bangladesh.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Willingly watched by Noelle Mateer: Chinese people are installing their own video cameras as they believe losing privacy is a price they are willing to pay for enhanced safety

The big deal by Jean-Paul Marthoz: French journalists past and present have felt pressure to conform to the view of the tribe in their reporting

Don’t let them call the tune by Jeffrey Wasserstrom: A professor debates the moral questions about speaking at events sponsored by an organisation with links to the Chinese government

Chipping away at our privacy by Nathalie Rothschild: Swedes are having microchips inserted under their skin. What does that mean for their privacy?

There’s nothing wrong with being scared by Kirsten Han: As a journalist from Singapore grows up, her views on those who have self-censored change

How to ruin a good dinner party by Jemimah Steinfeld: We’re told not to discuss sex, politics and religion at the dinner table, but what happens to our free speech when we give in to that rule?

Sshh… No speaking out by Alison Flood: Historians Tom Holland, Mary Fulbrook, Serhii Plokhy and Daniel Beer discuss the people from the past who were guilty of complicity

Making foes out of friends by Steven Borowiec: North Korea’s grave human rights record is off the negotiation table in talks with South Korea. Why?

Nothing in life is free by Mark Frary: An investigation into how much information and privacy we are giving away on our phones

Not my turf by Jemimah Steinfeld: Helen Lewis argues that vitriol around the trans debate means only extreme voices are being heard

Stripsearch by Martin Rowson: You’ve just signed away your freedom to dream in private

Driven towards the exit by Victoria Pavlova: As Bulgarian media is bought up by those with ties to the government, journalists are being forced out of the industry

Shadowing the golden age of Soviet censorship by Ak Welsapar: The Turkmen author discusses those who got in bed with the old regime, and what’s happening now

Silent majority by Stefano Pozzebon: A culture of fear has taken over Venezuela, where people are facing prison for being critical

Academically challenged by Kaya Genç: A Turkish academic who worried about publicly criticising the government hit a tipping point once her name was faked on a petition

Unhealthy market by Charlotte Middlehurst: As coronavirus affects China’s economy, will a weaker market mean international companies have more power to stand up for freedom of expression?

When silence is not enough by Julian Baggini: The philosopher ponders the dilemma of when you have to speak out and when it is OK not to[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]Generations apart by Kaya Genç and Karoline Kan: We sat down with Turkish and Chinese families to hear whether things really are that different between the generations when it comes to free speech

Crossing the line by Stephen Woodman: Cartels trading in cocaine are taking violent action to stop journalists reporting on them

A slap in the face by Alessio Perrone: Meet the Italian journalist who has had to fight over 126 lawsuits all aimed at silencing her

Con (census) by Jessica Ní Mhainín: Turns out national censuses are controversial, especially in the countries where information is most tightly controlled

The documentary Bolsonaro doesn’t want made by Rachael Jolley: Brazil’s president has pulled the plug on funding for the TV series Transversais. Why? We speak to the director and publish extracts from its pitch

Queer erasure by Andy Lee Roth and April Anderson: Internet browsing can be biased against LGBTQ people, new exclusive research shows[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]Up in smoke by Félix Bruzzone: A semi-autobiographical story from the son of two of Argentina’s disappeared

Between the gavel and the anvil by Najwa Bin Shatwan: A new short story about a Libyan author who starts changing her story to please neighbours

We could all disappear by Neamat Imam: The Bangladesh novelist on why his next book is about a famous writer who disappeared in the 1970s[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]Demand points of view by Orna Herr: A new Index initiative has allowed people to debate about all of the issues we’re otherwise avoiding[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]Ticking the boxes by Jemimah Steinfeld: Voter turnout has never felt more important and has led to many new organisations setting out to encourage this. But they face many obstacles[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg is a dissenting voice. Throughout her career she has not been afraid to push back against the power of the crowd when very few were ready for her to do so.![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were.

The coronavirus outbreak began with censorship. Censorship of doctors in Wuhan to stop them telling citizens what was going on and what the risks were. The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.

The Spring 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at our own role in free speech violations. In this issue we talk to Swedish people who are willingly having microchips inserted under their skin. Noelle Mateer writes about living in China as her neighbours, and her landlord, embraced video surveillance cameras. The historian Tom Holland highlights the best examples from the past of people willing to self-censor. Jemimah Steinfeld discusses holding back from difficult conversations at the dinner table, alongside interviewing Helen Lewis on one of the most heated conversations of today. And Steven Borowiec asks why a North Korean is protesting against the current South Korean government. Plus Mark Frary tests the popular apps to see how much data you are knowingly – or unknowingly – giving away.