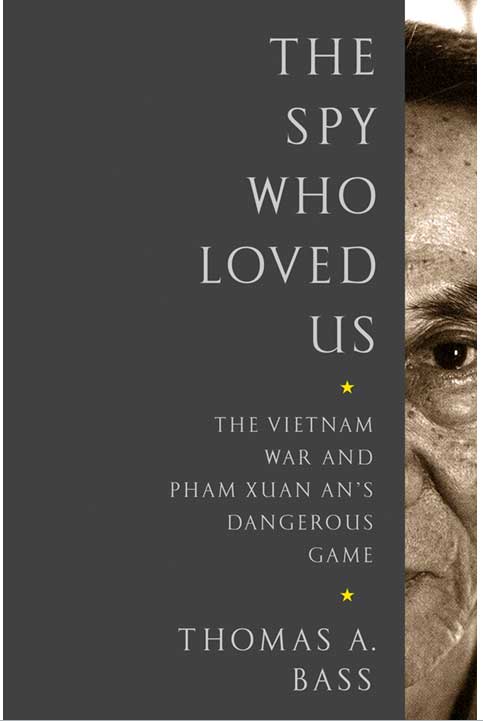

By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

A generation of Vietnamese writers has been forced into silence or exile |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

With the censor’s boot on their necks, a generation of Vietnamese writers has been forced into silence or exile. To report on their plight, I met with three of the country’s best-known authors: Bao Ninh in Hanoi, Duong Thu Huong in Paris, and Pham Thi Hoai in Berlin. Each had his or her own story to tell about censorship, arrest, banishment, or silence—realities that are becoming increasingly dire in Vietnam.

Bao Ninh (whose real name is Hoang Au Phuong, with Bao Ninh being the name of his family’s native village) was a seventeen-year-old student when he enlisted in 1969 as an infantryman in the 5th Battalion/24th Regiment/10th Division. He would spend six years fighting his way down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, surviving some of the war’s deadliest battles, before his regiment captured Saigon’s Ton Son Nhut airport in 1975. Of the five hundred men who joined his military unit in 1969, Ninh is commonly reported to be one of ten who survived.

Son of Hoang Tue, former director of Vietnam’s Linguistics Institute, Bao Ninh went back to school after the war and finished college in 1981. He worked briefly in a biology lab at Vietnam’s Science Institute and then picked up his pen to become a writer. In 1984, the thirty-two-year-old former soldier enrolled in the second class admitted to the Nguyen Du Writers School (named after the celebrated Vietnamese poet who wrote The Tale of Kieu). For his school thesis, Ninh wrote a novel about his war-time experience. “The Sorrow of War” began circulating around Hanoi in roneo form in the late 1980s. This stenciled duplication, similar to a mimeograph, was published in 1990 under the anodyne title Fate of Love. The original title was restored in a 1991 edition and then removed again when Fate of Love was reissued in 1992. The book won a major literary award and became instantly famous—too famous, apparently. A denunciation campaign was launched against Bao Ninh, his literary award was retracted, and his book went out of print. In fact, it went out of print for a decade. “The time is not right” to republish it, he was told. Fate of Love reappeared in 2003, but it was not until 2006—fifteen years after its original publication—that The Sorrow of War reappeared in Vietnam. The Vietnamese use a variety of euphemisms to describe this gap in Bao Ninh’s literary career, but the correct term is censorship. He was not thrown in prison or banned. In fact, he was rewarded for his silence, but he was censored, nonetheless.

Translated into English by Vietnamese poet Phan Thanh Hao and Australian journalist Frank Palmos, The Sorrow of War sparked another literary sensation when it was published in London in 1993. The book revealed that Vietnam’s veterans on the winning side suffered the same trauma and disillusionment as the losers. Hailed as a great novel, comparable to Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, The Sorrow of War has been republished in a dozen languages and named by the Society of Authors as one of the fifty best translations of the twentieth century.

While the novel was becoming a best-seller in the West, in Vietnam the book reverted to being passed hand-to-hand in pirated editions. Bao Ninh stopped writing, or, to be more precise, he stopped publishing. He took a government job, and his son was allowed to leave the country to study economics at the University of Massachusetts. The Sorrow of War is currently widely available in Vietnam, but its two successor volumes remain unpublished.

At my first meeting with Bao Ninh in Hanoi in 2008, we talked about his unpublished books. He assured me the works had been written, gave me their titles, and described their plots. I have to say that I have not personally verified the existence of these manuscripts, which have assumed a status in Vietnamese literature comparable to Captain Ahab’s great white whale—doubted by many, believed by some, seen by few. The subversive nature of Bao Ninh’s trilogy is revealed only after confronting the shock of the first volume. The Sorrow of War may be a great war novel, but it holds a double surprise for readers in the West by revealing the bitterness of NVA soldiers, the soldiers who won the war. They were betrayed by incompetent commanders and self-serving politicians. They were scorned by a post-war generation that wanted to forget the incredible suffering inflicted on Vietnam during thirty years of war and turn instead to making money. The survivors of the war are ravaged by guilt, attacked by bad dreams. They drink too much, brawl too much, and drift all too often from failure to suicide. They display all the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, shell-shock, battle fatigue, or whatever we call the soul-sucking misery that invades a soldier’s bones at the sight of men killing other men.

The “friendly, simple peasant fighters … were the ones ready to bear the catastrophic consequences of this war, yet they never had a say in deciding the course of the war,” writes Kien, the narrator of the novel, who, like its author, spent a decade fighting Americans in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. “We have so many of those damned idiots up there in the North enjoying the profits of war, but it’s the sons of peasants who have to leave home,” he writes in a manuscript that turns out to be the book we are holding in our hands.

At war’s end, the former infantryman is detailed into recovering the corpses of his fallen comrades. “Over a long period, over many, many graves, the souls of the beloved dead silently and gloomily dragged the sorrow of war into his life.” He returns to his native Hanoi in 1976 to find the city consumed by careerism, graft, corruption, and all the other ailments of an emerging Asian Tiger. The political propaganda is ham-fisted. His former fiancée is a prostitute. He joins the ranks of the “traumatized misfits” who survived the war, works as a journalist, and writes a novel that sits abandoned on his desk, until the pages blow away in the wind.

“Those who survived continue to live,” writes Kien. “But that will has gone, that burning will which was once Vietnam’s salvation. Where is the reward of enlightenment due to us for attaining our sacred war goals? Our history-making efforts for the great generations have been to no avail. What’s so different here and now from the vulgar and cruel life we all experienced during the war?”

“In this kind of peace it seems people have unmasked themselves and revealed their true, horrible selves,” Kien says to a fellow veteran. “So much blood, so many lives were sacrificed—for what?”

“I’m simply a soldier like you who’ll now have to live with broken dreams and with pain,” his colleague replies. “But, my friend, our era is finished. After this hard-won victory fighters like you, Kien, will never be normal again.”

Kien is wracked by the kind of survivor guilt that comes from knowing “that the kindest, most worthy people have all fallen away, or even been tortured, humiliated before being killed, or buried and wiped away by the machinery of war.” He is left with the “appalling paradox” that “Justice may have been won, but cruelty, death, and inhuman violence have also won.”

On the two occasions when Bao Ninh was allowed to travel to the United States (he visited Boston in 1999 and Texas in 2005) he gravitated to the war veterans in the crowd. They swapped reticent greetings, established whether they had carried guns or flown airplanes, and then started drinking, letting the silence fill with the ghosts of departed friends. Bao Ninh had more dead friends than the Americans, and they died more gruesome deaths, but dead is dead, and he bore no grudges as he sat among his fellow soldiers. “Soldiers never say ‘sorry’ to each other,” he told me later. “They have nothing to apologize for.”

When former U.S. marine Wayne Karlin met Bao Ninh at a hotel café in Hanoi in 2007, Karlin was reminded of another Vietnam veteran turned writer, Tim O’Brien. “Both men are compact, their faces not so much sharp as sharpened, their eyes bright, at times with a flare of pain, at times with a gleefully malevolent intelligence, a sardonic, challenging grunt’s stare. And they both smoke like hell,” wrote Karlin in his book Wandering Souls (2009).

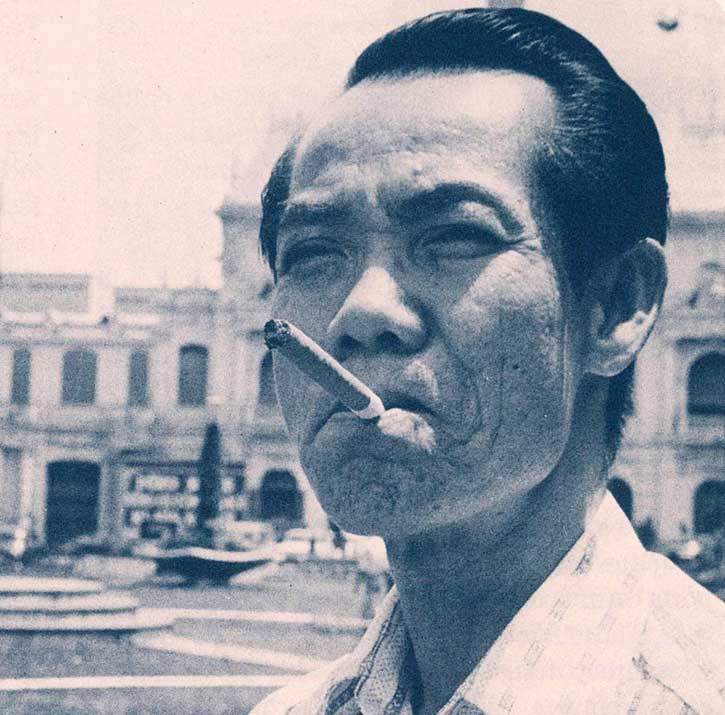

I am not a former soldier who fought in Vietnam, but the war was the cloud under which I came of age, and I seized the chance to begin traveling to Vietnam when the country opened to outsiders in the early 1990s. I met Pham Xuan An on my first trip in 1991, when the journalist-spy was still under police surveillance, and I kept returning to see him as I wrote my New Yorker profile and then my book, both entitled The Spy Who Loved Us. After An’s death in 2006, I visited Vietnam again two years later to talk to sources reticent about speaking while he was alive, and it was on this trip that I first met Bao Ninh.

Part 10: Eyes in the back of his head