By Thomas A. Bass

Today Index on Censorship continues publishing Swamp of the Assassins by American academic and journalist Thomas Bass, who takes a detailed look at the Kafkaesque experience of publishing his biography of Pham Xuan An in Vietnam.

The first installment was published on Feb 2 and can be read here.

Vietnamese censors have a totalizing view of history |

About Swamp of the Assassins

|

About Thomas Bass

|

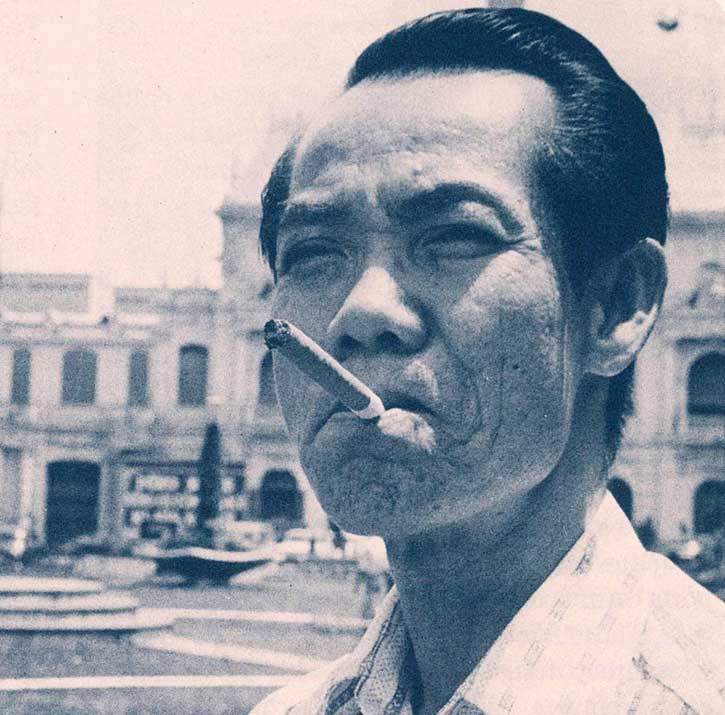

About Pham Xuan An

|

Contents2 Feb: On being censored in Vietnam | 3 Feb: Fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature | 4 Feb: Hostage trade | 5 Feb: Not worth being killed for | 6 Feb: Literary control mechanisms | 9 Feb: Vietnamology | 10 Feb: Perfect spy? | 11 Feb: The habits of war | 12 Feb: Wandering souls | 13 Feb: Eyes in the back of his head | 16 Feb: The black cloud | 17 Feb: The struggle | 18 Feb: Cyberspace country |

I write to Long, asking him to remove his footnotes. The poor man is now the mouse in the middle, caught between an exigent author and equally demanding censors. As we descend into the fine points of Vietnamese history and geography, my editor and I embark on a voluminous correspondence. The nature of this correspondence is exemplified by Rung Sat, the Swamp of the Assassins, which is the first item that Long has tagged for a footnote.

Southeast of Saigon, bordering the city’s main shipping channel to the sea, Rung Sat is the tidal mangrove swamp that for many years was home to the Binh Xuyen river pirates. The French had used the river pirates to help manage their colonial operations in Vietnam. Bay Vien, head of the pirates, had been elevated to the rank of general and given Saigon to run as a personal fiefdom. He owned the Hall of Mirrors, the largest brothel in Asia, with twelve hundred employees. He ran the Grand Monde casino in Cholon and the Cloche d’Or casino in Saigon. Bay Vien’s lieutenant was named chief of police in the capitol region, which stretched sixty miles from Saigon to Cap Saint Jacques. Bay Vien’s most lucrative operation, with a share of the proceeds going to the French government, was the opium trade that stretched all the way from Laos to Marseille. The Swamp of the Assassins also served as a communist staging area during the Vietnam war, and the river pirates themselves had briefly doubled as communists, before they switched to the other side.

Before retiring to Paris, where he could be seen strolling down the Champs Elysees with his pet tiger on a leash, Bay Vien used to hide in the Rung Sat swamp when things got too hot in Saigon. This was the case in 1955, after legendary spook Edward Lansdale arrived in town. Intent on knocking the French from their colonial perch and replacing them with a client government loyal to the United States, Lansdale launched a military campaign against the Binh Xuyen. Vietnamese army troops fought the pirates house-to-house for control of Saigon. More soldiers were involved in this week-long battle than in the famous Tet Offensive of 1968. Five hundred people were killed, two thousand wounded, and another twenty thousand left homeless. This proxy battle between France and the United States marked the transition from the First Indochina War to the Second.

Pham Xuan An claimed that he learned everything he knew about spying from Edward Lansdale. Lansdale was An’s patron as he began his career in military intelligence, and it was Lansdale who recommended that An study journalism in the United States. Because of the Swamp’s importance for colonialists, communists, river pirates, and spies, I had done a lot of archival work to verify its position in Vietnamese history. This is why I was particularly displeased to find a footnote saying, “The author is wrong.”

It is not called Rung Sat but Rung Sac, said Long, thereby turning the Swamp of the Assassins into the Forest of Seacoast Shrubs. (Rung means forest, but when dealing with wet mangrove forests, one might plausibly call them swamps. Sat is a Sino-Vietnamese combining word meaning death, as in am sat, to assassinate.) The government has renamed the Swamp because the government says this was never its correct name. And why is this? Because the government maintains that south Vietnamese have been distorting the country’s language and inadvertently displaying their ignorance for centuries. Southerners pronounce words ending in “t” as if they ended in “k” or a hard “c.” Thus, Rung Sac mistakenly became Rung Sat because southerners can’t spell correctly and are often confused by two words that sound the same. Undoubtedly, the communist officials behind this renaming were also sensitive about having used Rung Sat as a staging area during the American war. They didn’t want to be confused with swamp-dwelling assassins.

The issue might plausibly have been resolved by saying that the area used to be called x and is now known as y. But Vietnamese censors don’t work this way. They have a totalizing view of history. They reach back through time to correct errors retroactively. Even in quoted speech, Bay Vien and Lansdale would be forced to talk about the forest of seacoast shrubs. One can imagine what kind of stilted prose this produces, as anachronisms and communist terminology are inserted into the historical record. I had no choice but to mount a campaign proving, “The editor is wrong.”

I send Long a variety of French and Vietnamese maps, including a 1955 Vietnamese map showing military operations against the Binh Xuyen river pirates. I send maps from U.S. Naval Operations in the area, a copy of President Richard Nixon’s citation to the Rung Sat Special Zone Patrol Group, and a 1974 U.S. Academy of Sciences research report on Rung Sat. I send a 2010 Google satellite map, with the area marked Rung Sat, and I even send a photo of a bus leaving Ho Chi Minh City, with its scheduled destination clearly marked as Rung Sat.

Long comes back with his own “proof and evidence,” including the web site for the Rung Sac Resort and Restaurant, and some real estate prospectuses for housing developments that are financed, I presume, by local Party officials. I press the argument through more emails, until Long eventually writes, “I agree to remove the footnote about Rung Sat entirely.” As we discuss the rest of the footnotes, Long and I return to fighting hand-to-hand in the hedgerows of literature. Every email exchange becomes the Swamp of the Assassins Redux, until finally Long proposes “to remove wrong footnotes or footnotes concerning your mistakes,” I graciously accept his offer.

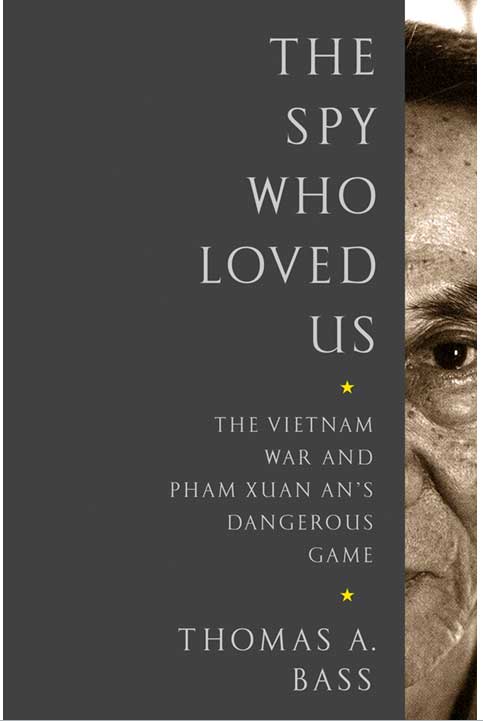

Next we turn to discussing the title of the book. “The Spy Who Loved Us” could be translated as “The Spy Who Loved America,” or, more poetically, as “America’s Best Enemy,” except that the censors reject these titles. As Long explains, “‘America’s Best Enemy’ is good, but somewhat sensitive. Why ‘best enemy’? Is this implying that Pham Xuan An was not entirely loyal to the revolutionary cause?” After further reflections on “the right viewpoint,” Long admits that “the issue proves to be more intricate than we initially thought.” Later I receive word that “The Spy Who Loved America” has been “immediately rejected” by Vietnam’s “publishing authorities.”

By this time, the people helping me review the manuscript (all of whom wish to remain anonymous) have compiled a list of phrases, sentences, and paragraphs that have been bowdlerized or pruned from the text. When I send this list to Long, he replies, “I assure you that the translator did not omit any sentences or paragraphs. He only highlighted sensitive phrases. The omissions or modifications are mine.”

In October 2010, Long writes to say that he is “tired of this project” and discouraged by having the book rejected by two state-owned publishing companies. He is trying to secure a publishing license from a third company, but people are telling him that the upcoming 11th Communist Party Congress, in the spring of 2011, makes it a “sensitive time” for publishing in Vietnam. This is a delicate moment “when everybody takes non-action to avoid complexities,” he says.

Writing to my agent in December 2010, Long says, “We understand the impatience of our author! But the situation is worse than you imagine. Another state-owned publisher has refused to issue a publishing license for our translation. Clearly, it is a highly-sensitive book at this moment in time. Everything is now hanging in the wind.”

When Long writes to tell me that another batch of publishers has refused to give him a license, I imagine the process as something akin to Random House having to clear a book through the Pentagon Publishing Company. If Pentagon Press won’t ink the deal, then Random has to go to publishing houses owned by Homeland Security or the FBI. These negotiations must be prolonged and humiliating, and, in a gift-giving culture like Vietnam, they must also be expensive.

I cool my heels through 2011, waiting for the Communist Party to shuffle a new set of rulers into place. In February 2012, I write to Long, wishing him a happy Water Dragon year and asking if he would kindly provide me with a list of all the governmental bodies that have so far been involved in censoring my book.

A month later, he writes back to apologize for being out of touch. He says he has left Nha Nam to go to work as an editor at a company that publishes math books for children. I feel a twinge of conscience, fearing that I might have been responsible for this change in jobs. “About the license to publish The Spy Who Loved Us,” he writes, “Nha Nam has been applying and still continues to apply to several publishers for a publishing license, not stopping at any time as you maybe think. I have asked for the latest information and was told that officials at Nha Nam still hope that the book will be published.”

“Officially, only state publishing houses are permitted to produce printed books,” Long explains. “So a privately-owned (non-state) company like Nha Nam must participate in so-called joint publication, in order to publish a book under the aegis of a state publishing house and pay a publication fee to this publishing house.”

“Technically, there is no censorship in Vietnam,” he says, “but directors or editors-in-chief of the publishing houses are sometimes required to remove sensitive items, or even are timid enough to let the book go unpublished (this is our case). This kind of action we call self-censorship, and it is the Gordian knot of the Vietnamese publishing industry.”

Long attaches to his email a copy of Vietnam’s Law on Publishing, a twenty-two-page document that does indeed say quite plainly, in Article 5.2, “The State shall not censor works prior to their publication.” The rest of the document is devoted to contradicting Article 5.2, as it enumerates what is “prohibited during publishing activities.” This includes “propaganda against the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (Article 10),” the incitement of war and aggression, the “spread of reactionary ideology, depraved life styles, cruel acts, social evils and superstition, or destruction of good morals and customs.” Other sections are devoted to the protection of Party, military, defense and other kinds of state secrets. Also forbidden is the “distortion of historical facts,” particularly those “opposing the achievement of the revolution.”

Long tells me that my new editor at Nha Nam is Ms. Nguyen Thi Thu Yen, who appears to be doing double duty as the person who negotiates foreign contracts. After our months of emailing back and forth, Long and I had prepared a second set of galleys, stripped of footnotes and corrected, at least as far as my advisors and I could push it. The manuscript is still bowdlerized and rewritten in dozens of places. All criticism of China has been removed. So too are any references to reeducation camps, graft, corruption, mistakes made by the Communist Party, and other “sensitive” subjects. Unfortunately, Long’s text will soon be supplanted by another, officially-licensed version. Again, I have misunderstood the nature of Vietnamese publishing. After all these months, my book has not yet been censored. It has undergone a kind of pre-censorship review, but the serious work of scrubbing sensitive material from the text has yet to begin.

Part 3: Hostage trade