25 Jun 2020 | Magazine, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”What do citizens in South Korea, Italy and Spain think about the long-term consequences of signing up to Covid-19 apps? Our reporters Silvia Nortes, Steven Borowiec and Laura Silvia Battaglia report for Index on Censorship magazine.” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”114058″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

SOUTH KOREA

Kim Ki-kyung, a 28-year-old who lives in Seoul, is used to the idea of his mobile phone tracking his movements, so he wasn’t bothered when he learned that his government would have access to his location data as part of efforts to contain the coronavirus outbreak.

He is far from the only one being tracked in this way. Several times a day, the millions of smartphones in South Korea bleat in unison with alerts from governments that users cannot opt out of receiving. When COVID-19 cases are diagnosed, the age and gender of the patients is disclosed to the public, along with the routes the patients took in the days before their diagnosis, so that others can avoid those places.

While the system raises issues of privacy, Kim thinks the potential benefits outweigh the concerns. “Everyone is at least somewhat reluctant to share personal data with the government, but the tracking app allows the authorities to monitor people who are in self-quarantine, and will allow epidemiological surveys to be done faster,”Kim said.

“The government system sounds terrible at first but it really isn’t all that different from regular smart services, like Google Maps or Nike Run Club,”Kim said.

Kim says he follows, through the news, how the government plans to handle the data gleaned from the program, but isn’t much worried about the data being used for some nefarious purpose somewhere down the road. He feels the more urgent task is containing the public health crisis.

SPAIN

In Spain, our interviews found respondents were more concerned about the use of personal information collected by monitoring apps, than in the other countries. The main conclusion drawn from the interviews is that people do not trust this system completely and fear data might be misused by the government and private companies, perhaps because some people have memories of what it was like living under the General Franco dictatorship.

Juan Giménez, 28, agreed with using these apps “only for controlling the spread of the virus”. Cristina Morales, 26, considers it “a violation of privacy, but, at the same time, it is appropriate to guarantee the citizens’safety and prevent confinement violations”.

Ana Corral, 22,said it is “OK as long as we know which information is used exactly, how it will be used and where the data is saved. If the goal is to know if you might have infected or been infected, that is fine”.

Some also mention social good as a priority. “There are always individual sacrifices for the common good”, said Manuel Noguera, 40. For Eduardo Manjavacas, 40, “the end justifies the means.” “Everything made for a global good and with a clear privacy policy is welcome. We live in a digital age, our data is studied daily for commercial purposes”, said Amelia Rustina, 30, while Sabina Urraca, 36, added she is “ready for that sacrifice. I would like to trust individual responsibility, but I don’t.”

On the other hand, older people are more reluctant, and many claim they would not register in these apps at all.

ITALY

They trust the government but with some doubts; they believe that giving up part of their privacy is a negotiable asset to protect public health; they want more reassurances on the functioning of the tracking app, wishing to know who will keep the sensitive data after the end of the pandemic.

These are the attitudes of Italian citizens of all ages relating to the use of a Covid-19 tracking app.

Index spoke to 50 Italian citizens – aged between 20 and 60, of different parts of the country, different professions and different backgrounds – about their thoughts on the Immuni tracking app announced by the Italian government as part of its approach to Covid-19.The Immuni app was preceded by a similar experiment in the Italian region most affected by the pandemic: Lombardy, where some of them live.

Federica Magistro, 22, university student, and Anna Pesco, 60, a teacher, living in Milan have downloaded the app in Lombardy, and are currently using it. They also plan to use the national app. Both hope that the remaining 60% of Italians also think the same way, so it maximises its use to of the entire population. Federica said: “I think I should trust those who are developing it and the government that offers it”, while Tesco said: “I would like maximum transparency and I would like to have absolute guarantee on the cancellation of my data at the end of the pandemic.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Jun 2020 | Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

CREDIT: Donna Grethen/Ikon

In some ways, it’s a good thing there are no parties at the moment, I would be the person trapping you in the corner, explaining the difference between centralised and decentralised Bluetooth contact-tracing apps, and why de-centralised is better for your privacy, and why some governments are so keen to use the other kind to get more data.

If you’re lucky, we might move the conversation on to how weird it is that Google and Apple are co-operating to design their own, decentralised, privacy-protecting, software for contact-tracing apps – and how it’s even weirder that the two tech giants are effectively forcing governments around the world to use that system.

They want their app to work properly on Apple or Android phones (i.e. most smartphones), because an effective app needs about 80% of smartphone users to run it.

I mean, Silicon Valley protecting our privacy against our own governments? Unprecedented times, indeed.

At this point, let’s suppose that I pause to sip my beer and you make your escape. If we were both using a contact-tracing app, the fact we’d been close together would already have been logged.

We might never have to share that information, especially if neither of us is diagnosed with Covid-19 in the near future, but our social connections have become fodder for state surveillance in a way that would be anathema in normal circumstances.

In South Korea, contact tracing has been very effective at containing Covid-19, but it also publicised the locations of Seoul nightclubs where recent infections took place, which led to the stigmatising of the gay community.

While I have reservations about particular uses of technologies, I accept that our social connections have become the vector for a nasty virus.

I would welcome an efficient system of contact tracing, which means one run by humans even though that makes it even more intrusive.

Coronavirus is a shared problem that needs shared solutions, and I have voluntarily signed up for other apps that request much more personal information to help researchers under-stand and track the pandemic.

But remember the wise words of former Chicago mayor Rahm Emmanuel (and Winston Churchill, and Niccolo Machiavelli): “Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

More importantly, remember that those in power have already remembered that. Measures being taken now to fight a deadly virus might turn out to be handy for other purposes later. Further research that could be useful for future pandemics- who could object to that?

You can read the whole of this article in our Summer 2020 issue, available by print subscription here and by digital subscription here.

18 Jun 2020 | Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

The summer 2020 edition of the Index on Censorship podcast looks at just how much of our privacy might we give away – accidentally, on purpose or through force – in the battle against Covid-19.

The podcast also features the world premiere of a lockdown playlet written exclusively for Index on

Censorship by Katherine Parkinson. Parkinson, best known for her role as Jen Barber in The IT Crowd, also stars as Sarah in the play, alongside actors Harry Peacock and Selina Cadell.

Arturo di Corinto speaks on the podcast about technological terms that have been used more and more in the crisis while Emma Briant discusses around techniques world leaders are using in the run-up to elections to stifle opposition.

Print copies of the magazine are available via print subscription or digital subscription through Exact Editions. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

17 Jun 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”With contributions from Katherine Parkinson, David Hare, Marina Lalovic, Geoff White and Timandra Harkness”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

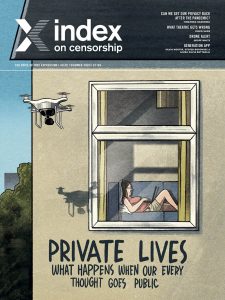

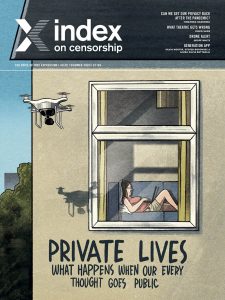

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It’s a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

In our In Focus section, we interview journalists in Serbia, Hungary and Kashmir who are trying to report the truth in places where the truth can be as dangerous, if not more, than Covid-19. And we have an interview with and poet from the playwright David Hare.

We have a very special culture section in this issue. Three playwrights have written short plays for the magazine around the theme of pandemics. V (formerly Eve Ensler), the author of The Vagina Monologues, takes you to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster; Katherine Parkinson of The IT Crowd writes about online dating during quarantine; Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily is inspired by recent events in his country in his chilling look at protest right now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report”][vc_column_text]

Back-up plan by Timandra Harkness: Don’t blindly give away more freedoms than you sign up for in the name of tackling the epidemic. They’re hard to reclaim

The eyes of the storm by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Spies are on the streets of Uganda making sure everyone abides by Covid-19 rules. They’re spying on political opposition too. A dispatch from Kampala

Zooming in on privacy concerns by Adam Aiken: Video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think

Seeing what’s around the corner by Richard Wingfield: Facial recognition technology may be used to create immunity “passports” and other ways of tracking our health status. Are we watching?

Don’t just drone on by Geoff White: If drones are being used to spy on people breaking quarantine rules, what else could they be used for? We investigate

Sending a red signal by Tianyu M Fang: When a contact tracing app went wrong a journalist was forced to stay in their home in China

The not so secret garden by Tom Hodgkinson: Better think twice before bathing naked in the backyard. It’s not just your neighbours that might be watching you. Where next for privacy?

Hackers paradise by Stephen Woodman: Hackers across Latin America are taking advantage of the current crisis to access people’s personal data. If not protected it could spell disaster

Italy’s bad internet connection by Alessio Perrone: Italians have one of the lowest levels of digital skills in Europe and are struggling to understand implications of the new pandemic world

Less than social media by Stefano Pozzebon: El Salvador’s new leader takes a leaf out of the Trump playbook to use Twitter to crush freedoms

Nowhere left to hide by Kaya Genç: Privacy has been eroded in Turkey for many years now. People fear that tackling Covid-19 might take away their last private free space

Open book? by Somak Ghoshal: In India, where people are forced to download a tracking app to get paid, journalists are worried about it also being used to access their contacts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”In Focus”][vc_column_text]

Knife-edge politics by Marina Lalovic: An interview with Serbian journalist Ana Lalic, who forced the Serbian government to do a U-Turn

Stage right (and wrong) by Jemimah Steinfeld: The playwright David Hare talks to Index about a very 21st century form of censorship on the stage. Plus a poem of Hare’s published for the first time

Inside story: Hungary’s media silence by Viktória Serdült: What’s it like working as a journalist under the new rules introduced by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán? How hard is it to report?

Life under lockdown: A Kashmiri Journalist by Bilal Hussain: A Kashmiri journalist speaks about the difficulties – personal and professional – of living in the state with an internet shutdown during lockdown

The truth will out by John Lloyd: Journalists need to challenge themselves and fight for media freedoms that are being eroded by autocrats and tech companies

Extremists use virus to curb opposition by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Covid-19 is being used by religious militia as a recruitment tool in Yemen and Iraq. Speaking out as a secular voice is even more challenging

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Culture”][vc_column_text]

Masking the truth by V: The writer of The Vagina Monologues (formerly known as Eve Ensler) speaks to Index about attacks on the truth. Plus a new version of her play about living in a nuclear wasteland

Time out by Katherine Parkinson: The star of The IT Crowd discusses online dating and introduces her new play, written for Index, that looks at love and deception online

Life in action by Lucien Bourjeily: The Lebanese director talks to Index about how police brutality has increased in his country and how that informed the story of his new play, published here for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Index around the world”][vc_column_text]

Putting abuse on the map by Orna Herr: The coronavirus crisis has seen a huge rise in media attacks. Index has launched a map to track these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Endnote”][vc_column_text]

Forced out of the closet by Jemimah Steinfeld: As people live out more of their lives online right now, our report highlights how LGBTQ dating apps can put people’s lives at risk

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe”][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Read”][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Listen”][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index’s South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question