21 Sep 2016 | Events, mobile

What’s it like to be an author of a banned or challenged book? How can librarians support authors who find themselves in this situation? To mark Banned Books Week, Vicky Baker, deputy editor of Index on Censorship magazine, will chair an online discussion with three authors on 29 September, followed by a Q&A.

It is free to join, although attendees must register in advance.

The contributors are:

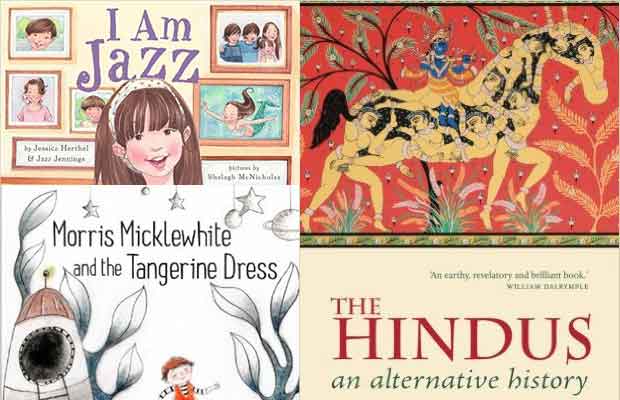

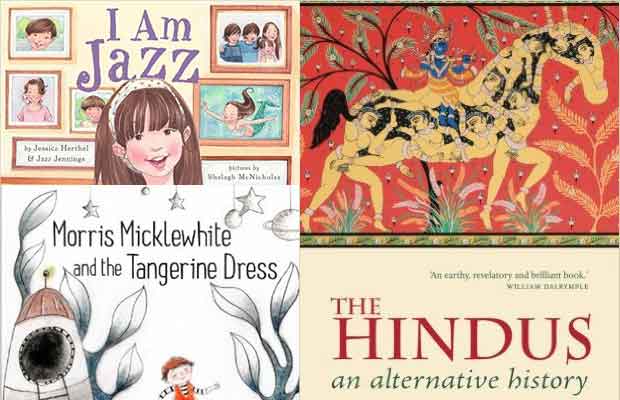

- Christine Baldacchino, author of Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress, a children’s book about a boy who likes to wear a dress, which “highly concerned” some parents when it was read in US schools.

- Wendy Doniger, a professor of religious history at the University of Chicago and author of numerous academic works. Her 2009 book The Hindus: An Alternative History was recalled, and destroyed, by the publisher Penguin India in 2014, after a lawsuit was filed, claiming the work denigrated Hinduism

- Jessica Herthel, a graduate of Harvard Law School, who co-wrote the children’s picture book I Am Jazz, with Jazz Jennings, a transgender activist and YouTube/television star. In 2015, an elementary school in Wisconsin cancelled a reading of the book after a group threatened to sue.

The webinar has been arranged by Sage Publications, in conjunction with the American Library Association.

When: Thursday 29 September, 4pm GMT / 11 EST

Where: Online

Tickets: Free, registration required.

1 Oct 2015 | Academic Freedom, mobile, News, United States

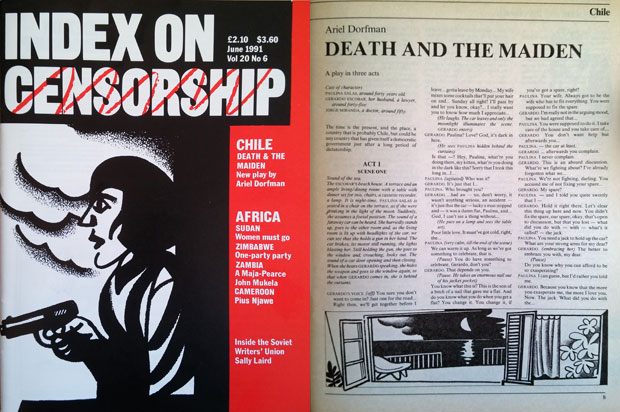

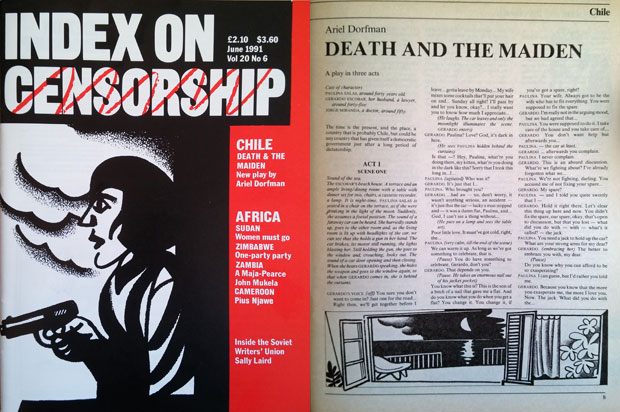

Death and the Maiden, Ariel Dorfman’s play, was first published in English in the June 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Parents and students at a high school in New Jersey have launched a petition to have books, including the play Death and the Maiden by Chilean playwright Ariel Dorfman, removed from mandatory reading lists and be “replaced with material that uses age appropriate language and situations”.

The petition, directed to Rumson Fair Haven high school, has gathered 222 signatures and asks “the administration institute a policy, whereby parents must sign a permission slip if assigned reading material, films or any media contains profanities, explicit sexual passages or vulgar language”. It has prompted a counter-petition, stating that “banning books will only educate students to be more ignorant and dismiss ideas that are ‘not appropriate’ or disagree with one group’s ideas”, which has already overtaken the original petition with 753 signatories.

The calls to remove the book have coincided with Banned Books Week (September 27 – October 3), which celebrates freedom to read and aims to draw attention to censorship of books.

Death and the Maiden was published in English for the first time in the summer 1991 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, and Dorfman’s short story Casting Away was published in the magazine’s September 2014 issue. The writer was forced to leave Chile in 1973 after the coup by General Augusto Pinochet. His life in exile has been very influential in his work as a novelist, playwright, academic and human rights campaigner.

Dorfman told Index: “For someone who has seen his books burnt on television by Chilean military, it is disturbing to witness the attempt in the United States to suppress the views of an author who explores the aftermath of what those military and their allies wrought, the way in which they burnt more than books, the way in which they seared the bodies and the minds of anyone who opposed their overthrow of Chile’s democratically elected government. One of the central issues in my play is the fear and silence that the protagonist, Paulina, has to deal with after she was imprisoned, raped and tortured. To silence the play in which she appears is to be an accomplice of that fear and to spread that fear to those readers and spectators who are trying to understand victimhood and how to survive it, how to heal both individually and as a society. Something that the United States must face, just as Chileans have.”

He added: “The government of General Augusto Pinochet deemed many books, many words, many thoughts, to be ‘inappropriate’. I am saddened by the attempt of some in America to be accomplices, however unwittingly, of that persecution of what they deem profane. And I am encouraged and gladdened to see so many comments to the petitions that stand up for freedom from censorship and the opening of young minds, helping the youth of tomorrow to create a world where the Paulinas – and so many others – will not be subjected to violence because of their beliefs. A world where my wife Angelica and I and our children would not be forced into exile or hear from afar news about the death of our friends in concentration camps.”

Further reading

Free thinking: Reading list for the Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2015

Judy Blume and her battle against the bans

Student reading lists: Threats to academic freedom

24 Sep 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Monday was the beginning of Banned Books Week, the annual celebration of the freedom to read and have access to information. Since the launch of Banned Books Week in 1982, over 11,300 books have been challenged, according to the American Library Association. To mark the occasion, Index on Censorship staff posed with their favourite banned books, and tell why it’s important that they are freely accessible.

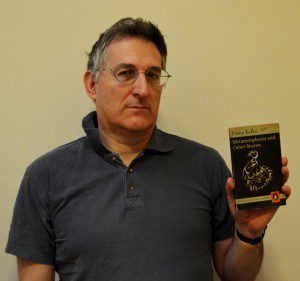

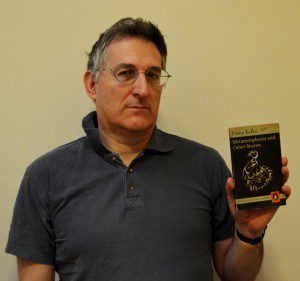

David Sewell (Photo by Dave Coscia)

David Sewell – Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

“Banned by the Soviet Union for being decadent and despairing and although they’re right in their analysis, the action to ban the book clearly is ludicrous. It’s a Freudian tale of Gregor Samsa who awakes one morning to find he has turned into a human sized bug and how his family react to this turn of events and treat him with revulsion and yes despair, since their main breadwinner is now out of commission. For a book about an insect grubbing about in filth, Kafka’s writing evinces some great beauty as did all his work despite the seam of despair underpinning many of them. Maybe this beauty through despair is what the Soviets meant by ‘decadent’. Kafka was a vital link between the end of the Victorian novel and the literary modernists and the influence of Freud’s ideas increasingly being used in characterisation. That is why ‘Metamorphosis’ is a significant book in the literary canon.”

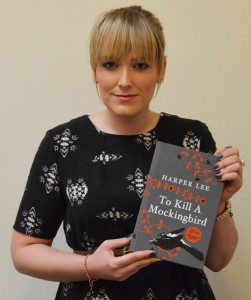

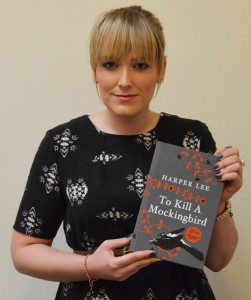

Aimée Hamilton (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Aimée Hamilton – To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee

“Because of its use of profanities, racial slurs and graphically described scenes surrounding sensitive issues like rape, Harper Lee’s award winning novel has been banned in many libraries and schools in the United States over its 54 year history. Having read this beautifully written book at school, I think it should be a freely accessible curriculum staple, to be both enjoyed and admired by all.”

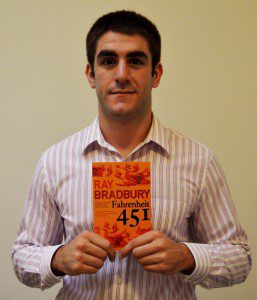

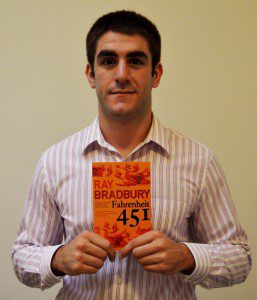

Dave Coscia (Photo by Aimée Hamilton)

David Coscia – Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

“Failing to or not choosing to see the irony, many schools in the United States banned Fahrenheit 451 based on its offensive language and graphic content. Bradbury’s grim view of a future where firemen are not people who put out fires, but instead set them in an attempt to burn books outlawed by the government, acts as a warning against state sponsored censorship, even if it’s not what he intended. Bradbury himself talks about Fahrenheit as a warning that technology would replace literature and cause humanity to become a “quick reading people.” What resonates with me about the novel is how prophetic that turned out to be. In the age of social media and instant information, humans, myself included, have gotten lazy and spend less time enjoying literature.”

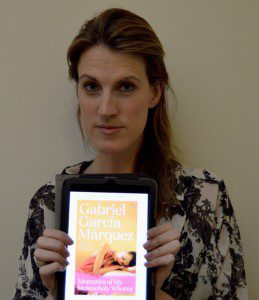

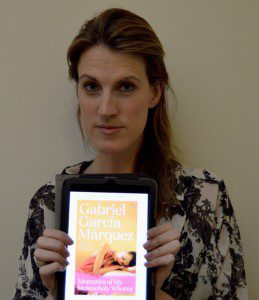

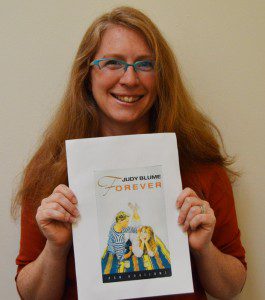

Vicky Baker (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Vicky Baker – Memories of My Melancholy Whores by Gabriel García Márquez:

“I picked this after reading how it was banned in Iran in 2007. Initially, it slipped through the censors’ net, as the Persian title had been changed to Memories of My Melancholy Sweethearts. It was on its way to becoming a bestseller before the ‘mistake’ was realised and it was whipped from shelves, accused of promoting prostitution. It’s classic tale of censors judging a book by its title.”

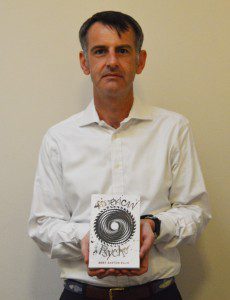

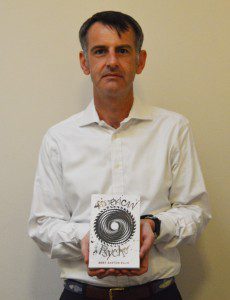

Sean Gallagher (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Sean Gallagher – American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

“No book, no matter how vilified or disliked, should be out of reach for anyone who wants to read it.”

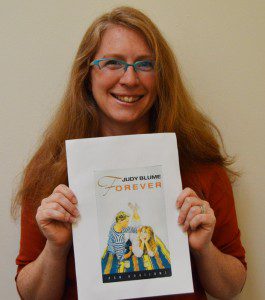

Jodie Ginsberg (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Jodie Ginsberg – Forever by Judy Blume

“I was one of the first girls in my class to own Judy Blume’s Forever and it was passed clandestinely from classmate to classmate until it finally fell apart, dog-eared (and highlighted in certain places…). It is a book that is powerfully linked in my mind – as for so many young kids – to the transition from childhood into the tricky years of teenage life. Reading it felt shocking, even dangerous. But also liberating.”

David Heinemann’s choice – Animal Farm

David Heinemann – Animal Farm by George Orwell

“It seems to have upset people from all ends of the political spectrum in one way or another at different times but what I love is that the story is actually quite ambiguous if you read it carefully, tearing pieces out of everyone and all angles. For its extraordinary imaginative power, the sheer audacity of its metaphors and it’s sharp alertness to the truths of life I treasure this book, having read it and been reminded of it so many times. I even adapted and staged the thing once, banning it is like depriving life of liquor.”

Fiona Bradley (Photo by Dave Coscia)

Fiona Bradley – Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

“I have chosen Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov because I think it is so deeply disturbing that it deserves to be read. It manages to convey some of the darkest human desires and emotions and these are exactly the kind of things that literature and art should explore. By banning it you are not protecting people but patronising them by refusing their right to judge it for themselves.”

This article was posted on 24 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Sep 2014 | Events

Wednesday, September 24, 9am PT/12pm ET/5pm BST

In 2013, there were 307 reported requests for books to be removed from America’s libraries, potentially putting those volumes out of reach of students, readers, and learners of all types. While every corner of the map faces unique issues related to library censorship, these issues also catalyze passionate freedom-to-read advocates dedicated to getting the books back on library shelves. In this one-hour webinar, we will “travel” from London, to South Carolina, to Texas, to California, to talk with three activists about the problems they face and their efforts to un-ban books as well as Congresswoman Linda Sanchez about why their efforts are so important.

London, UK: Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, will start us off by discussing issues faced outside of the U.S. and how Index chooses to respond.

Charleston, South Carolina: We will then travel to Charleston — where the graphic novel Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel has been a flashpoint in a university funding controversy — to hear from Shelia Harrell-Roye, a committee member from Charleston Friends of the Library. With the 2014 Banned Books Week focus on graphic novels, Harrell-Roye will discuss what her group has been doing to support this critically acclaimed book.

Houston, Texas: Moving westward, we will travel to Houston to hear from Tony Diaz, author, radio host, and leader of El Librotraficante. Diaz is a champion for banned books and for ethnic studies textbooks in both Arizona and Texas.

This banned books journey will end in California where Congresswoman Linda Sánchez of the CA 38th District, will offer some closing remarks about why the freedom to read is so important for our nation’s future. Afterward, our very own Ed McBride will wrap up the conversation from Thousand Oaks, CA.

Wednesday, September 24, 9am PT/12pm ET/5pm BST

Registration is free, but spaces are limited. (Note: On the following screens you will be asked to set your timezone preferences, then click register on the third screen to reserve your spot.)

Planning to attend? Let your social space know about this important event using #FreetoRead14.