Montenegro: Mayor accused of repeatedly undermining press freedom

In the past two months three threats to media freedom involving the mayor of Kolasin, a town in Montenegro, have been reported to Mapping Media Freedom.

Kolasin, which is the centre of a regional municipality of about 10,000 people, has a small media market that includes just one local newspaper named Kolasin and four correspondents working for the national dailies — Pobjeda, Dan, Vijesti and Dnevne Novine. There is no local TV station. The local government is run by a coalition of opposition parties — Democratic Front, the Social Democratic Party of Montenegro (SDP) and the Socialist People’s Party of Montenegro — while the Democratic Party of Socialists is the majority party in the national parliament and it runs the Government.

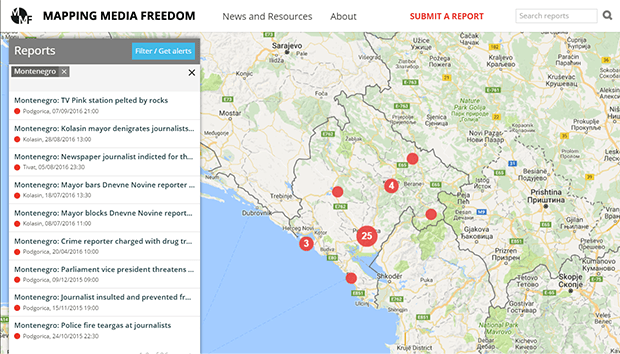

Mapping Media FreedomThis article is a case study drawn from the issues documented by Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project that monitors threats to press freedom in 42 European and neighbouring countries. |

In two of the cases, the local official, Zeljka Vuksanovic, an opposition politician belonging to SDP, had intentionally not invited Zorica Bulatovic, Kolasin correspondent for the governing party-aligned daily newspaper Dnevne Novine, to press conferences. In the third case, Bulatovic reported that she was verbally harassed.

Bulatovic told MMF that she is being blocked from reporting on Kolasin’s administration as a result of her critical reporting. In a statement to MMF, the mayor said that Bulatovic’s politically motivated reporting is the reason the journalist is not being invited to press conferences. “If you read her articles you will see why I am not communicating with her. You will see that those articles are not articles written by a journalist,” Vuksanovic wrote.

According to CDM, a media outlet owned by the Greek businessman Petros Stathis, who also owns the Dnevne Novine and another daily, Pobjeda, Bulatovic was not invited to an 8 July press session organised by the municipality. The news outlet also reported that Vuksanovic forbid municipality departments from cooperating with or providing information to Bulatovic.

Ten days later, on 18 July, the reporter was the only local journalist not included in a press conference organised after the visit of the national government’s minister for human and minority rights, Suad Numanovic, who called on officials to reverse their decision regarding Bulatovic.

The third incident occurred on 28 August when, in a speech, Vuksanovic said that the local ruling coalition had succeeded in triumphing over “crime, political corruption and media sputum”. Incensed by the speech, the five reporters that were present asked the mayor for an apology and further clarification on her points. The following day, Vuksanovic addressed her reply to four of the journalists, again omitting Bulatovic.

In the response, the mayor said that the term “media sputum” was not directed to the four journalists, but to the “media sputum that is hiding behind journalism as a profession”.

“It’s clear from the incident that the ‘media sputum’ comment was in fact verbal harassment of Zorica Bulatovic,” MMF project officer Hannah Machlin said. “This type of comment only serves to undermine the press as whole.”

Bulatovic told MMF that the negative climate between herself and the mayor has been going on for two years. She said that not only is she facing closed doors at the mayor’s office, but also at the municipal administrations.

The mayor disagrees with Bulatovic’s assertions, saying that the journalist is not barred from attending press conferences. “It is true that I don’t send her invitations for the press conferences, but I have never physically banned her presence at the press center,” Vuksanovic wrote MMF in an email.

Bulatovic maintains that she is barred from entering the press center. She also said that in the five years she has been reporting for Dnevne Novine, she has not had to make any corrections to her articles.

While Bulatovic is facing daily obstacles to her reporting, the four other local journalists are in a slightly better position since they are invited to press conferences. Yet, according to her, all the journalists face a common problem: despite the 2012 freedom of information law local politicians consistently throw up obstacles to documents or sources that would put them in a negative light.

“This whole situation is enormously impacting my work because it’s impossible for me to get an official statement from the local municipality,” Bulatovic said.

(Self)censorship always happens to someone else

Marijana Camovic, a journalist and head of the Trade Union of Media of Montenegro, said that while she was not fully aware of the situation in Kolasin, she did not know of another case where a reporter has been under a constant ban from press conferences. The usual practice for Montenegrin politicians is to publicly denigrate the work of journalists who are putting them and their administrations under scrutiny.

Camovic said the issue journalists in small communities with limited news sources, like Kolasin, most often grapple with is self-censorship.

“I personally think that self-censorship is an even bigger problem than censorship, as in that circumstance journalists know what is expected from them to write,” she said.

In her experience, it is rare for a journalist to be openly censored by their editor. The union recently undertook research, which will be published in October, that amongst other things asked journalists to comment on censorship and self-censorship in Montenegro. Camovic called the preliminary results very interesting.

“Generally, journalists answer that there are self-censorship and censorship in Montenegro. But, when you asked them whether they have personally been censored or succumbed to self-censorship, then only a few of them answer positively. So the conclusion is that there are self-censorship and censorship, but it always happens to someone else, which is paradoxical in itself,” Camovic said.

Her hypothesis is that journalists are probably ashamed to admit that they adjust to the official media policy to keep their jobs. It is not a secret that media outlets are politically engaged, she said.

“They openly support one and criticise the other political option. This is done without consideration of ethics and the role of the media in the democratic society.”

Mapping Media Freedom

|