9 Apr 2015 | mobile, News, Turkey

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

Another week, another social media ban in Turkey. I email a friend. to ask what are people making of this latest gross violation of free speech. “Nothing much,” comes the reply. “Lots of jokes though.”

Such is life these days in Erdoganistan, where every day brings a new censorship story, greeted now with what my Turkish friend calls “the humour of desperation”.

The latest ban on social media came, perhaps, with slightly more justification than previous attempts. Pictures of a state prosecutor, Mehmet Selim Kiraz, were circulated by the hard-left Revolutionary People’s Liberation Front (DHKP-C), which had taken him hostage. Hours after the pictures were released, Kiraz was dead. A court ordered that the picture of the dead man in perhaps his final moments be removed from certain sites, but the image proliferated. Hence the blocking of social media on Monday.

It was a case, as Kaya Genc wrote, of “burning the quilt to get rid of the flea”.

This is not unusual in Turkey. Last spring, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vowed to put a stop to social media after leaked wiretap recordings circulated on Twitter. Back in 2007, the whole of YouTube was blocked because of a video that insulted Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey. That ban lasted three years, and even then-president Abdullah Gul raised his objections. During his presidency, in fact. Gul was never the most reliable friend of the authorities when it came to online censorship. Even during the 2014 ban, he tweeted “”The shutdown of an entire social platform is unacceptable. Besides, as I have said many times before, it is technically impossible to close down communication technologies like Twitter entirely. I hope this measure will not last long.”

In 2008, in one of my personal favourite incidents of online censorship, Richard Dawkins’ website was blocked because of a dispute with ridiculous, but powerful Turkish creationist Harun Yahya.

One has to admire Turks’ sanguinity in the face of such idiocy. It is not as if the web and social media are marginal in Turkish everyday life. As with any other country where half-decent smartphones are available, Turkish billboards and TV adverts are festooned with the familiar logos urging us to like, share, follow and the rest.

But Erdogan and the authorities appear convinced that the web is something that can be harnessed and controlled and without any detrimental effect.

Not that the Turkish president is alone in this belief. During the 2011 London riots, David Cameron famously suggested shutting down social media, to the delirious whooping of the likes of Iran’s Press TV and China’s Xinhua news agency: “Look,” they gleefully pointed out. “The British go on about free speech, and at the first sign of trouble, they want to shut down the internet.” It was rumoured that the Foreign Office had to intervene to point out how bad Cameron was making its diplomats’ human rights lectures look.

But there is a special kind of madness at play in Turkey’s multiple bans, a particular persistence. Ban it! Ban it again! Harder!

The Turkish state at times seems too much like a cranky uncle to be taken seriously, staring confusedly at the Face-book and worrying that somehow it’s a scam because they once heard about an email scam on the radio and now the computer is plotting against them.

But the problem is that Turkey isn’t your confused uncle. Turkey is a hugely important country. The attitude toward web censorship tells us a lot about Erdogan’s regime: it’s erratic, volatile, prone to paranoia, and increasingly suspicious of new things and the outside world. The president is prone to talking about his and Turkeys enemies, internal and external. The recent moves against the Gulen movement (including its newspaper Zaman) and refreshed hostility towards the PKK suggest Erdogan is up for a fight. Last month, he lumped the two movements together declaring that they were “engaged in a systematic campaign to attack Turkey’s resources and interests for years.” – sounding for all the world like Stanley Kubrick’s Brigadier General Jack D Ripper obsessing over plots to taint our precious bodily fluids.

Invoking the age-old Turkish paranoia of hidden power bases, Erdogan said: “We see that there are some groups who turn their backs on this people […] Two different structures that use similar resources have been attacking Turkey’s gains for the past 12 years. One uses arms while the other uses sneaky ways to infiltrate the state and exploit people’s emotions. Their aim is to stop Turkey from reaching its goals.”

Endless obsession over threats does not make for healthy government, let alone democracy. Some suggest that in his outspokeness and utter partiality, Erdogan is already overstepping the mark and creating a defacto US-style presidency – a stated aim.

Men with enemies lists are best avoided, and probably shouldn’t be allowed to be in charge of anything. Erdogan has all the appearance of being one of those men, and he’s been quite clear that the internet is on the list, saying after the 2013 Gezi protests that “Social media is the worst menace to society.”

This attitude is not a rational, but paranoia never is. For all that Turks can laugh at the president and the system, deep down they must worry.

This column was published on April 9, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Jan 2015 | News, Turkey

Richard Howitt MEP is foreign affairs spokesperson for both the Labour Party and the Socialist and Democrat Group in the European Parliament and is a member of its joint parliamentary committee with the Turkish Parliament

As millions mourn the shooting of journalists in France, the European Parliament convening this week in Strasbourg today extended the fight for freedom of expression to legal threats, harassment and character assassination against free journalism in Turkey.

Indeed last weekend’s scenes reminded me of the hundreds of thousands who went on to the streets after the Turkish writer Hrant Dink was shot in 2007 and my deep regret that, despite the work of a foundation established by his widow, the situation in Turkey appears to have got worse not better in the intervening years.

A resolution voted for by MEPs was provoked by dawn police raids on newspapers and television stations in December that led to the arrest of 31 people, mainly journalists, on charges of terrorism – which carry some of the gravest sentences under the Turkish penal code.

Two of the leading journalists arrested openly admit sympathies for the US-based cleric Fethullah Gulen ,whose followers withdrew support from the country’s governing AKP party and whose so-called ‘movement’ does indeed deserve greater scrutiny.

Nevertheless reports suggest no evidence was presented of actual criminal intent against those arrested, with the crackdown fitting a pattern of legal harassment, smears and threats against those who provide political opposition to the government or who critically report on corruption allegations against it.

Our resolution also condemns the recent arrest of a Dutch journalist, demonstrating how foreign journalists are not exempt from attack.

Correspondents of The Economist, Der Spiegel and the New York Times in Turkey have all been threatened, with one CNN correspondent forced to flee the country after being accused of espionage.

Previous attempts to ban social media are also being revived in the country this week, in an apparent attempt to suppress reports Turkey’s intelligence organisation may have been implicated in the supply of arms to ISIS fighters in Syria.

As someone who is proud to call himself a friend of Turkey, and a keen proponent for the country’s accession to the EU, it is with a heavy heart I sign up to such criticisms.

However in negotiations I had to argue against opponents of the country seeking to use this latest incident to introduce wording that would have imposed immediate financial penalties against Turkey or put up new barriers in the membership negotiations.

I did so because politicians as well as journalists must not allow ourselves to be trapped in to self-censorship. On these arrests, it was our duty to speak out.

I am saddened explanations that the release of all but four of the journalists given to me and to my fellow MEPs by the Turkish representative in Strasbourg this week seemed wantonly to ignore the climate of fear and self-censorship which remains inflicted on the country’s press as a result.

It is the blatant denials that undermine trust and confidence with those of us who want to support reform efforts in the country, and which one very senior EU official told me had led to “desperation” in the telephone calls between Brussels and Ankara which followed the arrests.

Meanwhile, former prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, now elected as the country’s president, reacted characteristically by telling a news conference: “Nowhere in Europe or in other countries is there a media that is as free as the press in Turkey.”

The sober truth is that Turkey ranks 154 out of 180 in press freedom according to the Reporters Without Borders index last year.

The annual survey by the Committee to Protect Journalists, published only last month, showed Turkey amongst the top ten countries in the world for imprisoning journalists, ranking alongside Azerbaijan, Iran and China.

However, Erdogan’s protestations must be put in to a context where he also rebuffed European criticisms of the arrests saying the EU should “mind its own business”, and last week when he was prepared to partly attribute the Charlie Hebdo terrorist attack to “Western hypocrisy”.

Today’s European Parliament vote ascribes that hypocrisy instead to the government in Ankara.

I wonder whether the Turkish press will fairly report even this?

This article was posted on 15 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

14 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, France, News, Turkey

In October, Turkish cartoonist Musa Kart was the subject of a global solidarity campaign from his fellow artists. Kart was facing nine years in jail for insulting President Recep Tayyip Erodgan through a caricature for Cumhuriyet, where he commented on Erdogan’s alleged hand in covering up a high-profile corruption scandal. In response, his colleagues from around the world rallied in support of Kart, publishing their own #ErdoganCaricature on Twitter, and he was acquitted of the charges. This time, Kart is joining cartoonists in standing with Charlie Hebdo.

Cartoon courtesy Musa Kart

Kart told Index he feels “so sorry” and he has “lost his brothers” in last Wednesday’s brutal attack on the French satirical magazine’s offices, where 12 people — including cartoonists Stéphane Charbonnier aka Charb, Jean Cabut aka Cabu, Georges Wolinski and Bernard Verlhac aka Tignous — were killed.

Kart also ran into trouble with Turkish authorities back in 2005, when he was fined 5,000 Turkish lira for drawing then-Prime Minister Erdogan as a cat entangled in yarn. Kart puts the spotlight on Erdogan’s chequered history with cartoonists rights in a second piece, where the president declares that: “I condemn the attack. Ten years prison would have been enough for the cartoonists.”

TV: “Massacre in Paris. Twelve dead.” President Erdogan: “I condemn the attack. 10 years prison would have been enough for the cartoonists.”

Erdogan condemned the “heinous terrorist attack” and Turkey’s Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu joined last Sunday’s march for unity in Paris. Much has been made of the apparent hypocrisy of world leaders who have suppressed free speech at home, taking part in what many considered a defiant show of support for that very right.

As Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg pointed out, Turkey imprisons more journalists than any other country in the world. Index’s media freedom map has received 72 reports of press freedom violations from Turkey since May 2014 alone. In the wake of the attacks in Paris, other Turkish cartoonists have been threatened by pro-government social media users. Police also raided the printing press of Cumhuriyet, as it prepared to publish selections from today’s issue of Charlie Hebdo.

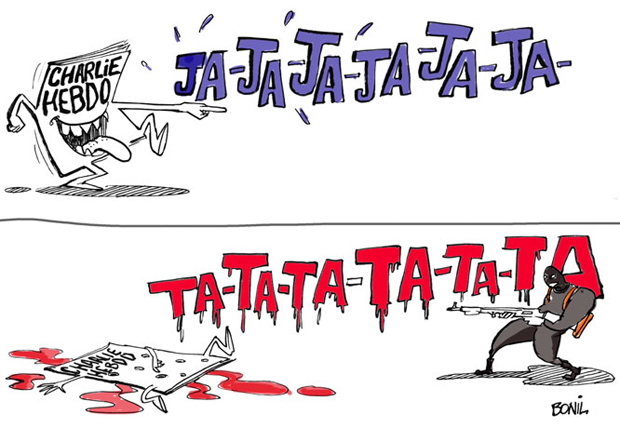

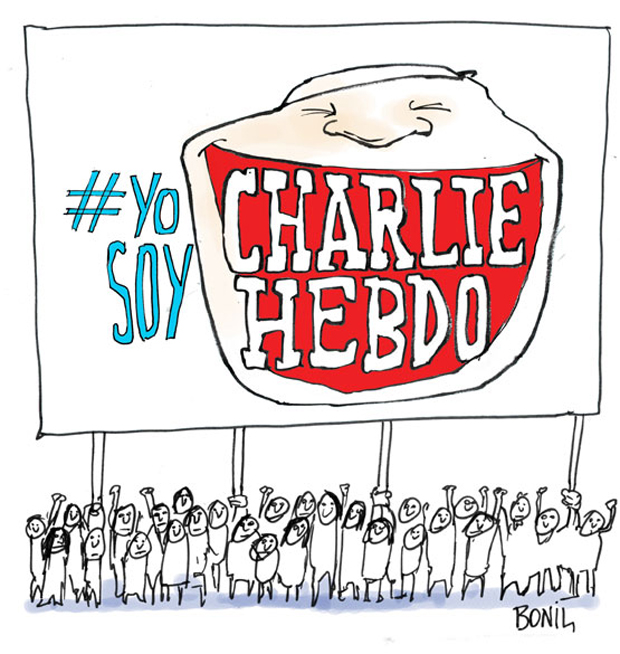

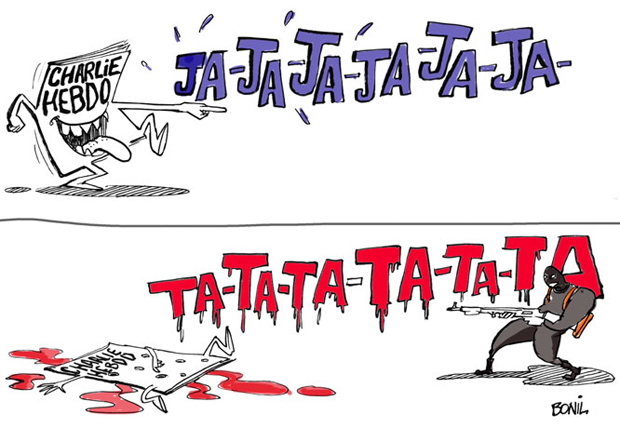

Ecuadorian cartoonist Xavier Bonilla — known as Bonil — has also been targeted for his work. In 2013, the country got a new communications law which allows the government to fine and prosecute the media. After drawing a cartoon for El Universo, based on a raid on the home of a journalist and opposition advisor, Bonil became a victim of the new legislation. President Rafael Correa — who has been known to personally file lawsuits against critical journalists — ordered that a case be opened against the cartoonist. It found that his piece had invited social unrest and should be “rectified”, while El Universo was fined $92,000.

“I believe that humour is the best antidote to fear and the best defence against abuses of power. I have been drawing for 30 years, and I am not going to back down,” he wrote in an article in the current issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

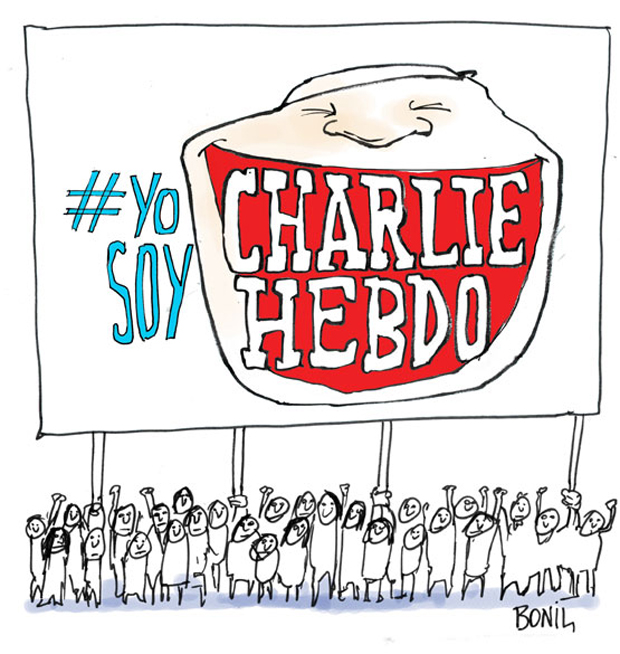

Below are his cartoons in support of Charlie Hebdo.

Cartoon courtesy of Bonil

“New ‘religion’: extremism”

#IAmCharlieHebdo

This article was posted on 14 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Dec 2014 | News, Turkey

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Photo: Philip Janek / Demotix)

What’s wrong with Turkey? Or, more to the point what is wrong with Turkey’s president that makes him so determined to fight, like a two a.m. drunk vowing to take on all comers?

In the past week alone, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his allies have launched attacks on his former ally Fethullah Gülen and his followers, novelists Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak, and even supporters of Istanbul soccer club Besiktas. It would be foolish to attempt to rank these attacks in terms of importance or urgency, but the attack on the Gülenites is the most interesting.

The Gülen movement was almost unknown to anyone outside Turkey and the Turkish diaspora until 2008, when Fethullah Gülen topped an online poll run jointly by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines. The poll was almost certainly hijacked by members of the movement, which its leader modestly claims doesn’t really exist (“[S]ome people may regard my views well and show respect to me, and I hope they have not deceived themselves in doing so,” Gülen conceded in an interview with Foreign Policy. “Some people think that I am a leader of a movement. Some think that there is a central organization responsible for all the institutions they wrongly think affiliated with me. They ignore the zeal of many to serve humanity and to gain God’s good pleasure in doing so.”)

The movement, known to some as “Hizmet”, is seen as bearing great power in Turkey. In a country well used to conspiracy theories about secret organisations — such as the perceived ultra-nationalist, ultra-secular Ergenekon — it is unsurprising that the Gülenists attract suspicion. Their cultishness does little to allay that sentiment.

Among the many weapons at the disposal of the movement are its newspapers, the Turkish Zaman and English-language Today’s Zaman. It was journalists from Zaman, among others perceived as Gülenites, who were arrested over the weekend, as reported by Index.

The move by Erdoğan against Gülenists is widely seen as part of Erdoğan’s defence against allegations of corruption within his party — allegations he believes are led by Gülenists within the police and other agencies.

With their journalists arrested, the Gülenists now find themselves facing the kind of censorship they themselves espoused not so long ago.

In 2011, journalist Ahmet Sik was working on a book called Army of the Imam, which was sought to expose the Gülenists’ connections with the police. The manuscript was seized by authorities. When Andrew Finkel, then a columnist with Today’s Zaman (and occasional Index contributor), submitted an article suggesting that the Gülen movement should not support such censorship, he was sacked by the paper. (The column subsequently appeared in rival English-language newspaper Hurriyet Daily News)

It’s tempting amid all this to wish for a plague on all their houses. But as one Turkey watcher pointed out to me, it’s inevitable that some innocents will get caught in the crossfire between the former allies in Erdoğan’s Islamist AK party and the Gülen movement.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the paranoid style of Turkish politics, pro-Erdoğan newspaper Takvim identified an external enemy in the shape of an “international literature lobby”.

The agents of that lobby, which is clearly anti-Turkish rather than pro-free speech, were identified as Orhan Pamuk and Elif Shafak. It is, in its own way, true that Shafak and Pamuk are part of the international literature lobby: London-based Shafak can often be seen at English PEN events, and Pamuk has long been identified as a literary and free speech hero around the world. But it is an enormous stretch to imagine that the novelists of the world are gathering in smoke-filled rooms plotting the overthrow of the Turkish state, rather than just hoping that Turkish people should be allowed write and read books in peace. Takvim went as far as to imagine that the authors were paid agents of the “literature lobby”, which is to make the terrible mistake of imagining there’s money in free speech. No matter: paranoia excels at inventing its own truths.

Amidst all this, less glamorous than Pamuk and Shafak, less powerful than Gülen and Erdoğan, fans of Besiktas football club too face persecution. The “Çarşı” group are claimed to have attempted a coup against the government after playing a prominent role in the Gezi park protests. Supporters of the tough working class Istanbul club, known as the Black Eagles, have a reputation for anti-authoritarianism and political activism. According to Euronews’ Bora Bayraktar: “While the court’s verdict is uncertain, what is known is that the Çarşı fans – often proud to be ahead of their rivals – have become the first football supporters’ group to be accused of an attempted coup.”

A source in Istanbul tells Index that when asked how he answered to the charge of fomenting a coup, one accused supporter replied: “If we’re that strong we would make Beşiktaş the champions!”, a prospect as unlikely for the underdog club as a dull but functioning liberal democracy seems for Turkey.

This article was posted on 18 December 2014 at indexoncensorship.org