Malian writer Étienne Fakaba Sissoko forced into exile

The acclaimed Malian professor and author Étienne Fakaba Sissoko, who was released from prison in March this year, has fled Mali with his wife and young children following abduction threats. He was one of the few voices left criticising the military government.

Sissoko spent a year in jail in the country’s Kéniéroba Central Prison for “harming the reputation of the state” and “dissemination of false news disturbing the public peace” as a result of the publication of his 2023 book, Propagande, Agitation, Harcèlement: La communication gouvernementale pendant la transition au Mali (Propaganda, Agitation, Harassment: Government Communication During Mali’s Transition).

Speaking to Index, Sissoko said after announcing that he was going to publish three books written while in prison – an essay on the resurgence of authoritarian regimes in West Africa, an economic analysis applied to Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, as well as a biography of persecuted public figure Djimé Kanté – attempts to silence him intensified.

Sissoko said there were two attempted abductions at his workplace, the University of Social Sciences and Management of Bamako (USSGB), one of the institutions created after the breakup of the former University of Bamako. He also faced constant surveillance by plainclothes agents and threatening visits to his home, anonymous calls, and social media messages such as ‘We know where you live’”.

The military regime running Mali has long shown its intolerance to Sissoko’s books, many of which have made uncomfortable reading for the junta.

He has written that the security situation in the country has worsened despite “help” from Russian mercenary group Wagner which the author says has committed human rights violations.

In 2020, violence was concentrated in the centre and north of the country, he said, but it now affects every region, including the capital, Bamako.

“Wagner has not brought lasting improvements to security,” he told Index. “It has been involved in serious human rights violations. Its presence serves to consolidate authoritarian power rather than protect civilians. Public opinion is divided: some view Wagner as a symbol of sovereignty, others as a foreign force with no popular legitimacy.”

Sissoko said relations with Russia now extend beyond the military sphere to media relations and diplomacy. Pro-Russian outlets and disinformation campaigns are promoted and Mali is aligned with Moscow positions at the UN.

These relations are being expanded in the higher education sector: 290 scholarships were granted for 2024–2025 to Malian students at Saint Petersburg University, and Bambara, Mali’s national language, is now being taught in some Russian institutions.

“In practice, Mali has become more dependent on Russia than it ever was on its Western partners,” he added.

“The break with France and several Western countries has had three main consequences: including the withdrawal of aid and the collapse of foreign investment and market isolation.

Mali once enjoyed a genuine democratic culture where freedom of expression was a core value, says Sissoko. The 2000s and 2010s saw the emergence of a pluralistic media landscape: the creation of new radio and television stations, the rise of social media, and vibrant citizen mobilisation.

Since the military coups of 2020 and 2021, this progress has been reversed.

Mali is ruled by military leader General Assimi Goïta who overthrew the government of then president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta in August 2020 following anti-government protests.

The cross-border Economic Community of West African States forced Goïta to hand over power to an interim government that was supposed to organise elections but the general staged another coup in May 2021.

Sissoko says repression has become systematic: arbitrary arrests of opponents and journalists, closure of media outlets that include RFI, France 24, TV5, Joliba TV) and dissolution of some movements such as student organisations.

“Today, Mali’s media environment falls into three categories: pro-regime outlets, financed or directly controlled by the military authorities; cautious media, practising systematic self-censorship to avoid reprisals; and independent voices, rare and often forced into exile or marginalised,” said Sissoko.

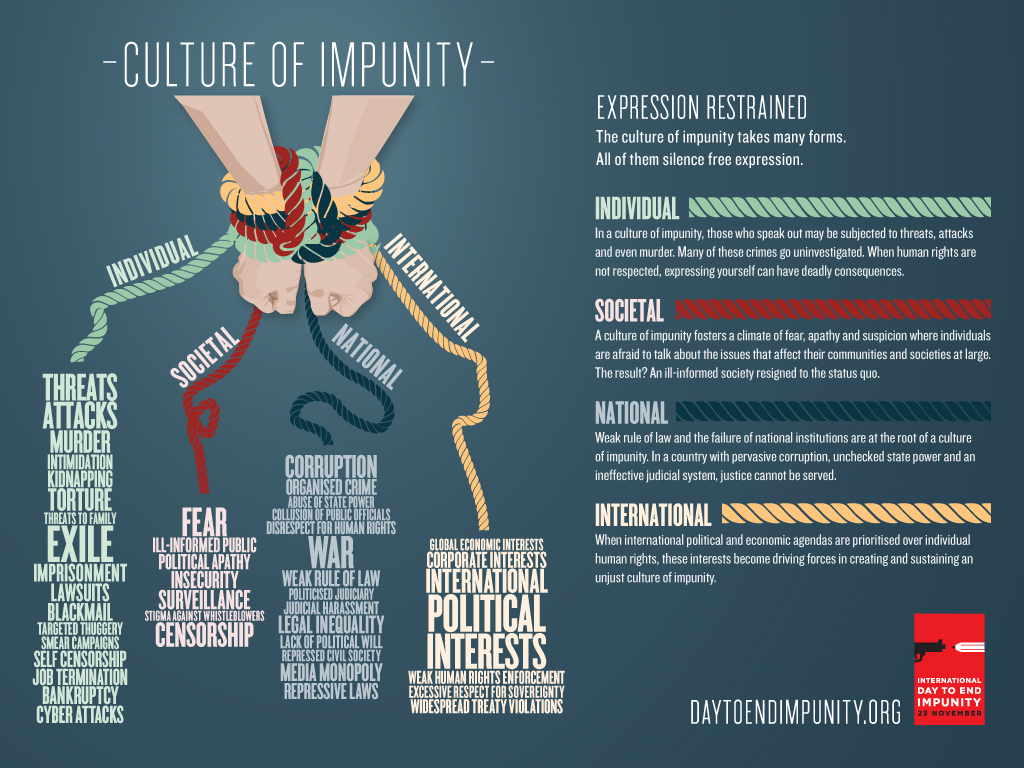

Opinions contrary to those of the government have also been criminalised by the country’s cybercrime unit, he added. Sissoko said as a result of heightened repression, Malians engage in digital self-censorship and modify their communication even in private as fear has become a method of governance.

Sissoko said in Mali researchers face severe political risks for any research deemed critical. He said there is an absence of independent, forward-looking research to inform public policy; lack of dialogue between academia and political decision-makers; chronic underfunding and lack of infrastructure for independent research.

He founded the Centre for Research and Political, Economic and Social Analysis (CRAPES) in Bamako to aim to fill that gap.

“Before 2020, university lecturers could address almost any topic freely. My own arrest in 2022 — the first time in Mali’s history an academic was imprisoned for research work — marked a turning point,” he told Index.

Since then: academics decline invitations to speak publicly on political topics, even in their own areas of expertise. Scholarly work linking political developments with current events has become rare; self-censorship is widespread,” he added.

“Students, too, avoid taking political positions in class. Fear has replaced critical thinking, eroding the university’s mission.”

The professor argued that these alternatives cannot replace the diversity and quality of former partnerships with western countries.

Sissoko’s coverage of the worsening state of freedom of expression in his books, Libertés en exil, pouvoir en treillis: Chronicle of an Authoritarian Drift in Mali (2020–2025) and De la transition à la régression: The Dissolution of Political Parties in Mali as a Symptom of Legal Authoritarianism has made him a target for the government.

He feels he was left with no choice but to leave the country with his family.

Sissoko told Index, “These systematic and organised threats aimed to prevent me from speaking out again. My family had to be evacuated for their safety. Even in exile, I remain under a suspended sentence, which illustrates the regime’s determination to maintain permanent judicial pressure.”