Pakistan: “Martyred” foes, drones and instability

When Shamsheer Khan, learnt about the drone strike on Hakimullah Mehsud, the Pakistani Taliban supremo, on Nov 1, the 45-year old taxi-driver in Karachi, went to the mosque and prostrated before God to help the young fighter. “I prayed that if he were fighting a jihad against the Americans, Allah should protect him and if he had expired in way of jihad, to elevate him to the highest position of an Islamic fighter.”

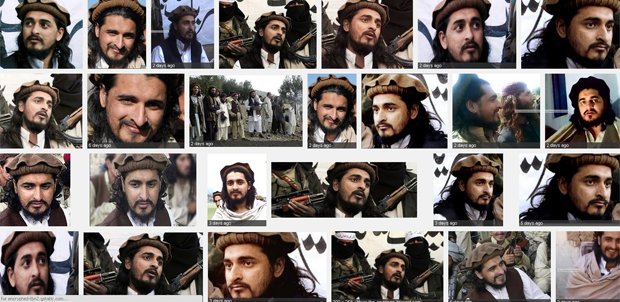

Mehsud was killed in a US drone strike in the Dande Darpakhel, in the North Waziristan tribal region of Pakistan, bordering Afghanistan. He had succeeded Tehrik Taliban Pakistan’s (TTP) Baitullah Mehsud, in 2009, after the latter was killed in a similar attack by the drones.

Mehsud has claimed to have orchestrated several fatal attacks on the Pakistan army and also had a hand in the 2010 suicide attack in Afghanistan in which seven CIA agents were killed.

Strangely, Khan’s empathy for a perpetrator of violence finds resonance across the country where anger against drones is high, a reason for such an extreme anti-American sentiment.

Shortly after Mehsud’s death was confirmed, leaders from religious-political parties like the Jamaat-i-Islami’s (JI) Munawar Hasan called him a “martyr” and Jamiat Ulema-i Islam’s (JUI) Fazlur Rehman went a step further saying anyone killed by US is a martyr.

The taxi driver justified the violence saying: “When the leaders of this country have sold their souls to the West, somebody has to bring them back to the true path of Islam and if violence is what is needed, then be that.”

But Mosharaf Zaidi, a political analyst has no illusions that Mehsud is none other than a “mass murderer.” Calling Mehsud “a martyr was a grave tactical error and a dangerously immoral thing to do,” he said, adding. “The TTP is a terrorist organisation that deserves neither any sympathy from Pakistan, nor from any other country,” he added.

Zahid Hussain, defence analyst and author blames it on a “complete disarray” he sees in Pakistan’s policy. “Nawaz Sharif wants to normalize relations with the US, but there is no clarity on how he wants to deal with the issue of rising militancy in Pakistan that also threatens the US interests in the region.”

When news of Mehsud’s death reached the rulers, the narrative changed slightly. Though not directly empathising with the TTP, Pakistan’s interior minister, Chaudhry Nisar said the drone attack had scuttled the peace process that the government was about to start with the Taliban. Imran Khan, also in favour of talks with the Taliban, threatened stopping the NATO supply line going through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, where his party, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) is ruling, if drone strikes did not end.

“The TTP shura [council] had frequently derided the notion of peace talks and, even before the death of Mehsud, had not committed to negotiations,” pointed out said Dr Pervez Hoodbhoy, noted peace activist and an academic.

Still, if negotiations have to happen, Zaidi said these “must begin with the organisation’s [TTP] acceptance of the Pakistani constitution and the sovereignty of the Pakistani republic over Pakistani territory.” He, however, was sceptical of saying “no sign of such an acceptance” seemed to exist.

To a nation, in the throes of daily violence, last week’s events have only led to historic bewilderment bordering on the dangerous. A wave of confusion seems to have enveloped the people blurring the distinction between a hero and a villain.

“It only confuses an already shattered national discourse in Pakistan about rule of law, national sovereignty and a bright future for Pakistani children,” said Zaidi.

Hoodbhoy finds Mehsud being termed a martyr incredulous. “It indicates some kind of collective mental disorder!” he said, adding: “The Pakistani mind, whipped into hyper anti-Americanism by the media and parties like PTI and JI, appears to have lost its sense of balance.”

To Zaidi, Pakistan’s handling of the TTP has been nothing short of tragic. He puts the blame squarely on both the government and political leaders who helped “create a narrative in which Mehsud, seems to have become a victim of drones.” He said the drone strikes would not exist if the Pakistani state had taken care of the criminals and terrorists that have been “festering and building up in FATA and beyond since well before 9/11”.

With the new TTP leader Mullah Fazlullah though, there is little doubt among the Pakistani people over who their foe and versus friend is. Fazlullah had virtually held the valley of Swat hostage and embarked on a systematic, violent movement to wipe out dissent back in 2007-2009. Last year it was his men who had shot Malala. Eventually the army had to step in and flush him and his followers out of the region.

To Hoodbhoy, this change of guard has given the Pakistani state a “narrow window of opportunity to hit Fazlullah and his band of terrorist thugs before he consolidates his power.”

But, he questioned: “Will we be able to find the courage and strategic wisdom? He answered it himself with a grim: “I doubt it!”

On 10 Nov, the Inter Services Public Relations, which is the official PR cell of the army, condemned the use of the word martyr to describe Mehsud, saying it misleading and irresponsible.

This article was originally published on 11 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org