Pakistan continues silencing dissent through selective web blocks

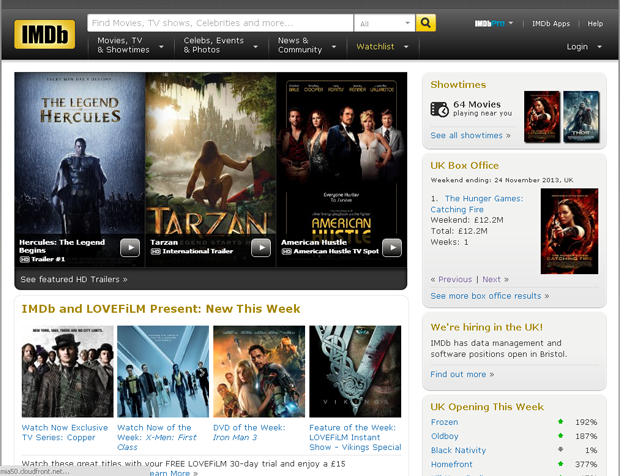

Urooj M, a former DJ on a Pakistani FM radio channel, also a film aficionado, was incredulous when she found the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had blocked the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

She tweeted: “SERIOUSLY #PAKISTAN, WHY ON EARTH WOULD YOU BAN #IMDB!!! COME ON, SERIOUSLY!!!???!!!! #FirstYoutubeNowIMDB #WTF.”

This widely used online entertainment news portal, a prominent source of reliable news and box office reports regarding films, television programmes and video games from all over the world, was blocked on 19 November, but the ban was lifted by 22 November.

Pakistan is notorious for blocking websites. It has banned more than 4,000 websites for what it considers objectionable material, including YouTube, in 2012 for a film that was deemed blasphemous by Muslims around the world. In 2011, in a particularly ill-thought-out move it announced censoring text messages containing swear words. In 2010, after a decision by the Lahore High Court, Facebook was blocked as a reaction to the ‘Everybody Draw Muhammad’ page that was seen as offensive to the prophet.

Users were given no reason for this sudden and selective ban. However, Omar R. Quraishi, a journalist had tweeted: “PTA official declined to give specific reason for ban on IMDB – said is placed for 3 reasons: “anti-state”, “anti-religion”, “anti-social”.

While these “targeted bans” are small irritants in his life, as he can easily by pass them, Ali Tufail, 26, a Karachi-based lawyer, finds them wrong on principle as he sees them infringing upon the fundamental rights of the citizen as given in Article 19 and 19 A of Pakistan’s Constitution.

He said the government must give users sound “reasons” why they block a certain website and “what benchmarks or what standards are used to come to the decision to enforce these sudden bans” and if there is a committee that takes these decisions, “we must be told who these people are.”

The same was endorsed by Nighat Dad of Digital Rights Foundation (DRF). “We strongly oppose any form of censorship employed on citizens, curbing their basic right to information.”

However, netizens believe the ban was enforced to block the movie trailer for The Line of Freedom, a film that highlights the issue of the crises in Balochistan province showing Baloch separatists abducted by Pakistani security agencies without charges in a bid to stamp out rebellion.

“Our team did a quick survey with the help of tweeters around the country,” said Dad. “We checked various other movie titles but only Line of Freedom seemed to be blocked on IMDb and several other websites were accessible otherwise.” The DRF termed it an “unprecedented event” because the government had “used all sorts of means to curb the dissidents’ views” from Balochistan.

“I didn’t even know there was a movie by this title which was giving the government so much heartburn and so I just had to see what was so unsavoury that the government had to block the entire website,” said Dad who watched the whole 30 minutes or so of it by circumventing the various firewalls. “This is what happens, when you forcibly close the internet, word gets around and people get curious!”

Malik Siraj Akbar, editor of the online Baloch Hal, who sought asylum in the United States, is not surprised at the ban. His own newspaper was blocked in November 2010 and even now the ban has not been completely lifted, he says. “Since 2010, it has been available in some parts of the country and not others and access has not been very consistent,” he said adding there were hundreds of other Baloch websites, “mostly those supportive of the nationalists that have been blocked”.

But Tufail added: “This is one battle which the government would find difficult to win as newer, maybe more objectionable [to Pakistani state] websites, will keep popping up which they would never be able to keep pace with,” terming such bans an “exercise in futility”.

There could be some truth in the story of the ban on the Baloch film. Because their voices remain unheard, several family members made a 700km journey on foot from Quetta to Karachi to see if that would make a difference.

Naziha Syed Ali, a journalist at English-language daily Dawn, had recently visited Awaran, a stronghold of the separatists in Balochistan, which had been badly affected by the earthquake on September 24. She said she got a sense of “hostility expressed mainly towards the army and paramilitary rather than Pakistan per se. Then again, the army is seen as a symbol of the country, so it’s pretty much the same thing.”

Ali said “More than fear, they don’t want to take help from what they see as an occupation force.”

According to her the “feelings of alienation have been greatly exacerbated by the issue of the missing people and the kill-and-dump tactics”.

In addition, while Ali found there to be “sufficient food for now”, there was dire need for health services and proper shelter “as the tents that have been distributed are not warm enough for winter”.

The problem is the army is not allowing international and local non-governmental organisations to carry out any relief work there. Instead, the charities run by religio-political organisations and even banned outfits are seen freely roaming about. For years, the state has kept a stony silence over the issue of the disappearances of the Baloch nationalists. Rights group say if the state lets the various organisations into the region, their dark secrets about grave human rights abuses, for now a national shame, may become a problem for it on the international front.

This article was published on 2 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org