Ukraine: Showing solidarity for a country in crisis

Walking around Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti square, months after the protest that enveloped the city and toppled the corrupt government of Viktor Yanukovych died down, is a strange experience. International attention has understandably shifted, the images now beamed across the world are from the ongoing crisis in eastern Ukraine. The capital is calm these days, so I don’t know exactly what I was expecting as I made my way down Mykhailivska street.

Tents still populate Maidan, with young and old lounging, talking and cooking in the May sunlight. I walked past sandbag barricades, and ones made of tyres painted in the blue and yellow of the Ukrainian flag. There were flags were everywhere — EU, American, British, and many more. I walked past the independence monument, juxtaposed against the new year tree, covered by protesters in posters, and yet more flags. Music was blaring out from the small stage facing these towering structures. The lyrics I couldn’t understand, apart from the cry of “Ukraina” in the chorus. I made my way past the Maidan press centre, towards a bridge which had a large banner emblazoned with names and faces hanging from it. The Hotel Ukraina behind me, I looked out over the square.

The only thing missing was the crowds. It felt like they had just taken a break — gone for lunch, to return at any moment. Perhaps I arrived with a naive “out of sight, out of mind”, mentality, subconsciously assuming that the square would to an extent have been cleared out. But Maidan seems to be, for now at least, a living monument to the profound change, and crisis, Ukraine is going through.

It was against this backdrop, and with the country’s general elections set for this Sunday, I travelled to Kiev to take part in the conference Ukraine: Thinking Together. The brainchild of Yale University history professor Timothy Snyder and the New Republic’s Leon Wieseltier, its purpose was “to meet Ukrainian counterparts, demonstrate solidarity, and carry out a public discussion about the meaning of Ukrainian pluralism for the future of Europe, Russia, and the world.” The guest list included academics like Bernard-Henri, Lévy Timothy Garton Ash and Ivan Krastev, and journalists like The New York Times’ Roger Cohen and The Atlantic’s David Frum. Former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt also made an appearance at the welcome reception.

One could question what, if any, effect the discussions of a group of intellectuals might have on the very real crisis on the ground. Over the weekend, there were among other things, a Crimean Tartar journalist was detained in Simferopol, while the Ukrainian military arrested two Russian reporters. But Kiev-based journalist Maxim Eristavi told me, and tweeted, that it was “surreal” to have the “intellectual powerhouse of the West in one room in Kyiv”. If nothing else, organising a big-name gathering to talk about Ukraine, in Ukraine, makes a bold statement — and one likely to be heard all the way to Moscow.

A range of topics were tackled in five days of panel debates and public lectures. The Maidan protest was applauded, with Wieseltier in his opening remarks calling it “one of the primary sites of the modern struggle for democracy”. Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, called Maidan a geopolitical move, but by a people rather than a government.

Bernard-Henri Lévy spoke of his recent visits to eastern Ukraine, explaining that while they might be fewer than in the Maidan, there are people in these areas who support a unified Ukraine. He contested what he believed to be the image presented in western media that people in the east are all separatists. While the point was made that flags, national symbols and the Maidan movement is not perceived as positively in all parts of the country as in Kiev, Constantin Sigov, professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla, argued that the Ukrainian crisis is first and foremost civil and political, not one of identity.

Russia’s foreign policy and Russian President Vladimir Putin were unsurprisingly recurring themes. “He has values. They are not our values, but they are values,” said François Heisbourg, chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, talking on the panel of geopolitics after Crimea. Writer Paul Berman argued, in the same panel, that Putin is acting from a position of weakness, and fear that Russia is not stable. Others, meanwhile, were uncomfortable with the term geopolitics, saying it legitimises Putin’s world view.

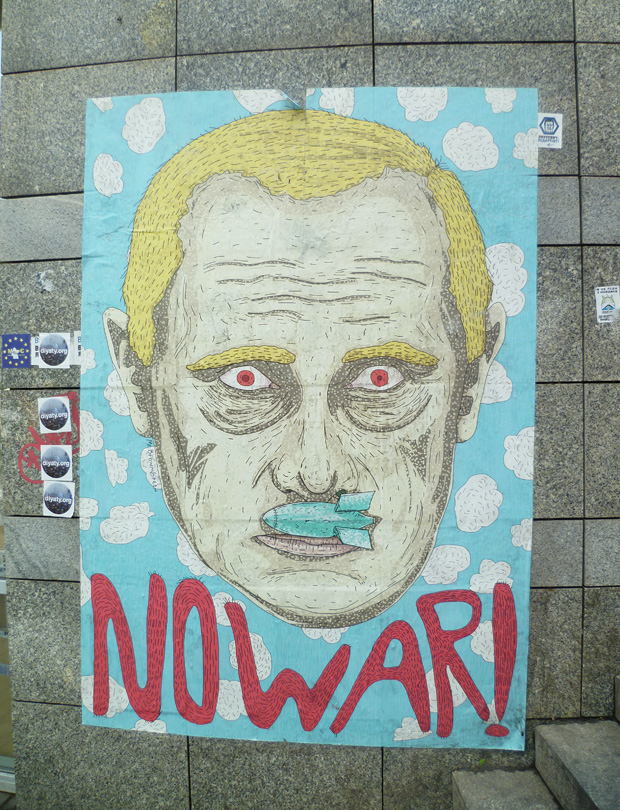

Russia’s propaganda strategy was also a hot topic and elicited strong responses, with one audience member referring to it as a weapon of mass destruction. “Propaganda is the beginning of bloodshed, it precedes bloodshed,” said Alexandr Podrabinek, editor-in-chief of Prima information agency, on the panel discussing whether rights make us human. State-run news channel RT, formerly Russia Today, got several mentions. Academic Anton Shekhovtsov argued that RT gives space to democratic consensus in its coverage, but also to left-wing, far right and libertarian narratives, and even conspiracy theories. Because each is treated in roughly the same way, the democratic narrative becomes just one of many. He said this explains why RT appeals to some people in the west, but stressed that they’re pushing an overall Russian agenda.

Podrabinek, despite dubbing RT “hateful”, argued that while there might be a temptation to shut down views we don’t like, this is not a good way of confronting them. If we want freedom of expression, he said, we can’t do that. On a related note, Carl Gersham argued that while Ukraine needs to be supported economically and militarily, they also need support in modernising the media landscape, to foster internal dialogue.

And while the regime was criticised by speaker after speaker, ordinary Russians and their rights were not forgotten. Sergei Lukashevsky, director of the Sakharov Museum and Public Centre, put the support for Putin into the context of fear. When people see that the state is cracking down on human rights again, he argued, they make themselves fit in — go into survival-mode. While rights exist formally in Russia, he explained the practical situation through an old Soviet joke: “Do I have the right? Yes. Can I? No.”

In a weekend of intellectuals discussing how to solve a crisis, novelist and non-fiction writer Slavenka Drakulic gave a sobering lecture on the role of intellectuals in causing crises, specifically the Balkan wars. To be able wage war, to kill, you have to create an enemy and dehumanise it, she argued. Here is where academics, poets, journalists came in handy in former Yugoslavia — by preparing people psychologically for conflict, “using words almost like bullets”.

And this leads well into the final panel of the conference, on the role of history and memory in politics, the difference between official history and collective and personal memories of the people, and how especially the former can be manipulated. We’re arguably seeing that today already, with Timothy Snyder saying that with events in Ukraine, a European revolution is being contested even as it’s happening. The Russian Ministry of Education is already writing new chapter to explain Crimea, said acclaimed Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov. “And Ukraine might have their version.”

After my trip to Maidan, I asked a Ukraine-based AP journalist what the future might bring for the square. There are only a specific type of people still there, she explained, and they might see how the elections go before they decide to stay or leave.

Or as Myroslav Marynovych, the founder of Amnesty International Ukraine, said during the conference — when there is democracy, there will be no need to go to Maidan.

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org