1 Apr 2022 | Hungary, News and features, Uncategorized

LGBTQI rights. Gender equality. Media freedom. The fate of liberties in Hungary hang in the balance as the nation heads to the polls on Sunday. With a falling currency, a mismanaged response to the pandemic still fresh to mind and a stronger opposition under United For Hungary – a coalition of six parties spanning the political spectrum – the election campaign has been the closest in years. But the war in Ukraine, right on Hungary’s border, has changed its course in unexpected ways. Below we’ve picked the most important things to consider when it comes to the April 2022 elections.

Basic rights could worsen

Since his election in 2010, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has whittled away fundamental rights in the country to the extent that Hungarian activist Dora Papp told Index in 2019 free expression had no more space “to worsen”.

Orban’s main targets have been people who identify as LGBTQI. Last year, amid global outcry, he passed a law that bans the dissemination of content in schools deemed to promote homosexuality and gender change. Seeking approval for this legislation, Hungary is holding a referendum on sexual orientation workshops in schools this Sunday alongside the parliamentary elections.

Orban also takes aim at the nation’s Roma and immigrants, and has revived old anti-Semitic tropes in his attacks on George Soros, a Hungarian-born Jewish philanthropist who Orban claims is plotting to flood the country with migrants (an accusation Soros firmly denies).

As for half of the population, Orban’s macho-style leadership manifests in rhetoric on women that is dismissive, insulting and focuses on traditional roles. Asked in 2015 why there were no women in his cabinet, he replied that few women could deal with the stress of politics. That’s just one example. The list goes on.

His populist politics have seeped into every democratic institution and effectively dismantled them. The constitution, the judiciary and municipal councils have all been reorganised to serve the interests of Orban. Education, both higher and lower, has seen huge levels of interference. Progressive teachers and classes have been removed. Even the Billy Elliot musical was cancelled after Orban called the show a propaganda tool for homosexuality.

But the media can’t freely report much of this

In response to claims of media-freedom erosion, the Hungarian government likes to point out that there are no journalists in jail in Hungary, nor have any been murdered on Orban’s watch. But as we know only too well there are many ways to cook an egg. Through gaining control of public media, concentrating private media in the hands of Orban allies and creating a hostile environment for the remaining independent media (think misinformation laws and constant insults), the attacks come from every other angle. Orban has even been accused of using Pegasus, the invasive spyware behind the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi, to target investigative journalists.

It’s little wonder then that in 2021 Reporters Without Borders labelled Orban a “press freedom predator”, the only one to make the list from the EU.

As election day approaches the attacks continue. In February, for example, pro-government daily Magyar Nemzet said it had obtained recordings showing that NGOs linked to Soros were “manipulating” international press coverage of Hungary, a claim instantly rejected by civil society groups.

Ukraine War has shifted the narrative, for better and worse

Given Orban’s track-record on rights, it comes as no surprise that he’s the closest EU ally of Vladimir Putin. This wasn’t a great look before 24 February and it’s even less so today, as the opposition are keen to highlight. They are pushing Orban hard on his neutral stance, which has seen him simultaneously open Hungary’s borders to Ukrainian refugees and oppose sanctions and the sending of weapons.

But Orban is playing his hand well. Fears of becoming embroiled in the war appear to be stronger in Hungary than anger at Putin’s aggression, many analysts says. Orban is claiming a vote for him is a vote for stability and neutrality, while a vote for the opposition is a vote for war. He’s even tried to cast his February visit to Moscow as a “peace mission”.

And though he has condemned the invasion, he has yet to say anything bad about Putin himself. Worse still, Hungarian media is blasting out Russian propaganda. Pundits, TV stations and print outlets are pushing out lines like the war was caused by NATO’s aggressive acts toward Russia, Russian troops have occupied Ukraine’s nuclear plants to protect them and the Ukrainian government is full of Nazis.

Anything else?

Yes. Orban met with a coalition of Europe’s far-right in Spain at the start of the year. They discussed the possibility of a Europe-wide alliance. What that looks like now in a post-Ukraine world is hard to tell. We’d rather not see.

Then there’s the fact that Serbia also goes to the polls Sunday. Like Orban, the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), led by president Aleksandar Vučić, has been unnerved by growing opposition. Also like Orban, they’re close to Putin and using the Ukraine war to their advantage – reminding people of the 1999 Kosovo war when NATO launched a three-month air strike. Orban and Vučić have developed close ties and will no doubt be buoyed up by each other’s victories should that happen on Sunday.

So will the Hungary elections be free and fair?

If the 2018 elections are anything to go by, they will be “free but not fair”, the conclusion of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), who partially monitored the 2018 election process. That’s the optimistic take. Others are fearful they will be neither free nor fair, so much so that a grassroots civic initiative called 20K22 has recruited more than 20,000 ballot counters – two for each of Hungary’s voting precincts – to be stationed at polling centres on election day with the aim of stopping any voting irregularities.

News from yesterday isn’t confidence-boosting either. Hungarian election officials reported a suspected case of voter fraud to the police. Bags full of completed ballots were found at a rubbish dump in north-western Romania, home to a large Hungarian minority who have the right to vote in Hungary’s elections. Images and videos shared by the opposition featured partially burnt ballots marked to support them. As of writing, no details have been provided of the actual perpetrators and their motives, and Orban has been quick to accuse the opposition of being behind the incident. Either way, it leaves a bad taste in the mouth.

24 Apr 2014 | Lebanon, News and features, Religion and Culture, Young Writers / Artists Programme

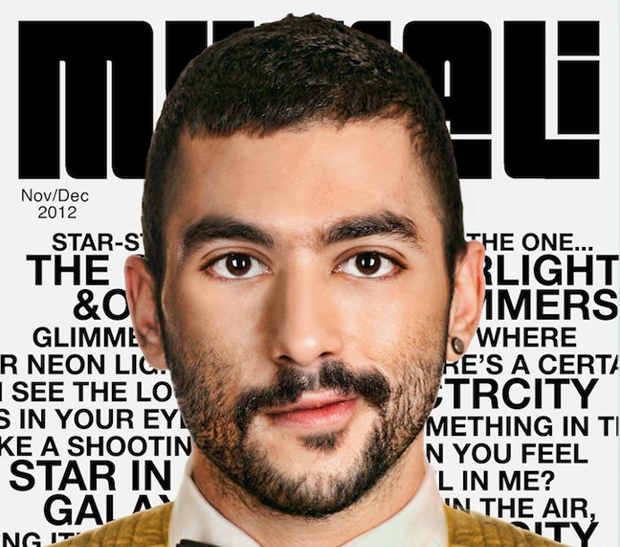

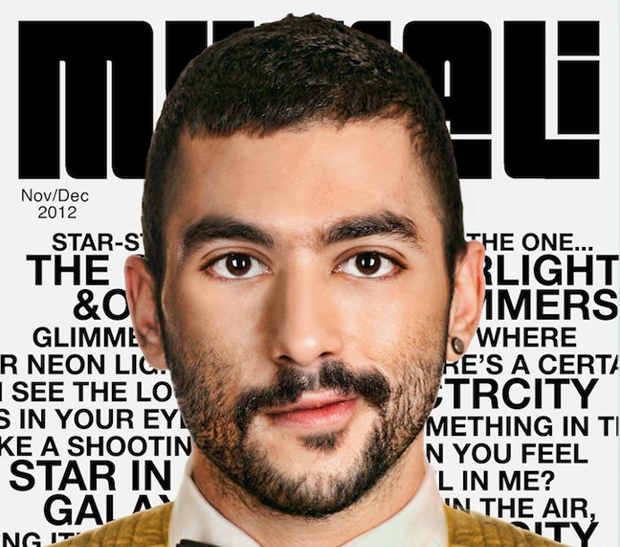

Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, is the lead singer of Mashrou’ Leila

While walking the streets of the upscale downtown district of Beirut, or sipping cocktails in one of El-Hamra’s bustling bars, one could easily forget that Lebanon is a country where civil liberties are still in debate.

Article 534 of the Lebanese penal code states: “Any sexual intercourse contrary to the order of nature is punished by imprisonment for up to one year.” The vaguely worded article has and is still being used to crackdown on the LGBT community in Lebanon. Compared to its neighbours in the Middle East, Lebanon has long been considered one of the least conservative countries in the region. According to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2013, 18% of the Lebanese population thinks that homosexuality should be accepted in the society, putting it way ahead of Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia where almost 97% of the population views homosexuality as deviant and unnatural.

The Lebanese Psychiatric Society issued a statement in early 2013 saying that: “The assumption that homosexuality is a result of disturbances in the family dynamic or unbalanced psychological development is based on wrong information” — making Lebanon the first Arab country to dismiss the belief that homosexuality is a mental disorder. On 28 January 2014, Judge Naji El Dahdah of Jdeideh Court in Beirut dismissed a claim against a transgender woman accused of having a same-sex relationship with a man, stating that a person’s gender should not simply be based on their personal status registry document, but also on their outward physical appearance and self-perception. The ruling relied on a 2009 landmark decision by Judge Mounir Suleimanfrom the Batroun Court that consenual relations can not be deemed unnatural. “Man is part of nature and is one of its elements, so it cannot be said that any one of his practices or any one of his behaviours goes against nature, even if it is criminal behaviour, because it is nature’s ruling,” stated Suleiman.

Despite the recent positives, being gay in Lebanon is still a taboo. In a country drenched in sectarianism, debates about homosexuality are easily dismissed in the name of religion and homosexuals are accused of promoting debauchery.

“People in Lebanon, and across the region, still act like homosexuality doesn’t exist in our society,” said Kareem, who requested that Index only use his first name. “I think it’s important that we start the conversation and get the issues out in the open, so people can start acknowledging it and then decide their stance on. The fight for our rights comes later on,” he added.

In 2013, Antoine Chakhtoura, mayor of the Beirut suburb of Dekwaneh, ordered security forces to raid and shut-down Ghost, a gay-friendly nightclub. “We fought battles and defended our land and honor, not to have people come here and engage in such practices in my municipality,” the mayor asserted.

Four people were arrested during the raid and brought back to municipal headquarters where they were subject to both physical and verbal harassment: forced to undress, enact intimate acts which included kissing, as well as being violently beaten. Marwan Cherbel, minister of interior at the time of the incident, backed the mayor’s actions, adding that: “Lebanon is opposed to homosexuality, and according to Lebanese law it is a criminal offence.”

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident. In a similar raid on a movie theatre in the municipality of Burj Hammoud known to cater for a gay clientele, 36 men were arrested and forced to undergo the now abolished anal probes — known as tests of shame. The raid came only a few months after Lebanese TV host Joe Maalouf dedicated an episode of his show Enta Horr (You’re Free) to exposing a porn cinema in Tripoli where it was claimed that young boys were being sexually abused by older men.

“The fact that these incidents received a lot of media coverage, some of which denounced the raids, is a sign that the public is little by little taking an interest in the issue of gay rights,” said Kareem. “Five or six years ago, this could have easily gone unnoticed. While the gay community might not be fully accepted or tolerated in Lebanon, it has been gaining a lot more visibility in recent years.”

Helem, a Beirut-based NGO, was established in 2004 to be the first organisation in the Middle East and Arab world to advocate for LGBT rights. In addition to campaigning for the repeal of Article 543, Helem offers a number of services, including legal and medical support to members of the LGBT community. Organisations like Helem and its offshoot Meem, a support group for lesbian women, had a huge impact on raising awareness and correcting misconceptions about homosexuality. Support from Lebanese public figures has also been on the rise in recent years. For example, popular TV host Paula Yacoubian and pop star Elissa have both shown support for the LGBT community in Lebanon via their Twitter accounts.

While the struggle to change the law continues, young artists have been challenging social norms through art. Mashrou’ Leila, a Beirut-based indie rock band, has sparked a lot of controversy thanks to their songs, in which they unapologetically sing about sex, politics, religion and homosexuality in Lebanon. In Shim el Yasmine, the band’s lead singer, Hamed Sinno, who is openly gay, sings about an old love, a man whom he wanted to introduce to his family and be his housewife. Director and art critic, Roy Dib, recently won the Teddy Award for best short film in 2014 at the 64th Berlinale International Film Festival with his film Mondial 2010. The film tells the story of a gay Lebanese couple on the road to a holiday weekend in Ramallah, Palestine. It tries to explore the boundaries that make it impossible for a Lebanese person to go into Palestine, as well as the challenges faced by a homosexual couple in the region.

The battle for gay rights in Lebanon is multilayered, and while change is starting to feel tangible, there is still a lot to be done.

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Feb 2014 | News and features, Religion and Culture, Russia

Human Rights Watch released a video documenting the treatment of LGBT Russians on 3 February ahead of the opening of the Sochi Winter Olympics.

Drawing a screen around the realities of life for Russian gays and lesbians, Russian president Vladimir Putin and the organizers of the Sochi Winter Olympic games are presenting a decidedly friendly face to international visitors.

Even though Sochi’s mayor, Anatoly Pakhomov, would prefer to believe “there are no gays” in his city, the mayor of the Olympic village, Elena Isinbayeva, offered to make LGBT athletes to feel welcome — despite her earlier homophobic comments. The girl band Tatu, most popular during the early 2000s when they exploited homoeroticism in their live appearances and videos, will perform at the opening ceremonies.

The real Russia has turned ugly and brutish toward its LGBT citizens.

The recent spate of homophobic violence has its roots in a controversial law that bars the promotion of non-traditional relationships as being equal to traditional relationships. While the law’s backers say they are protecting children, the effect has been to silence the push for gay rights by threatening fines for “homosexual propaganda.”

While official Russia will be demonstrating what it sees as tolerance in Sochi, a court in the city of Nizhniy Tagil will issue a ruling on the case of Elena Klimova – a young journalist who created a group on Vkontakte – Russia’s answer to Facebook. Klimova’s group, Children 404, contains letters from young LGBT people, who have been subject to physical and psychological attacks. Their letters to each other, according to Klimova, have been helping them cope with the pressure and continuing struggle for their rights. Klimova’s efforts to ease the isolation of LGBT children has drawn the ire of United Russia’s Vitaly Milonov, a proponent of the gay propaganda law, who has sued Madonna and been exposed as a bigot by Stephen Fry.

Klimova has also been active in raising concerns about the plight of a teen girl in the Bryansk region who has been put under administrative control by a local juvenile commission. Her crime? The girl openly identified “herself as a person with non-traditional sexual orientation and promote[d] information which misinforms minors about social equality of traditional and non-traditional relationship”. She will be monitored as if she were a criminal.

According to the latest Levada-Centre research, some 43% of Russian citizens consider homosexuality a bad habit, 38% reckon LGBT people should be “cured”, 47% say LGBT and heterosexuals are not socially equal and 73% approve the state’s effort to prevent public professions of an LGBT orientation.

The Russian Orthodox Church has done a lot to maintain these numbers.

Patriarch Kirill has repeatedly condemned equal marriage, saying in late January that marriage is “between a man and a woman, based on love, aimed at having children”. Kirill asked law makers to reflect his belief in drafting laws. Moscow Patriarchate’s spokesman Vladimir Legoida called equal marriage and homosexuality a sin in an interview to RIA-Novosti – the former Russian state news agency. Not to be outdone, Ivan Okhlobystin, an actor and former priest, said “gays should be burnt in ovens”.

In the meantime, on 3 February, the regional court of Kamchatka sentenced three people to 9-12 years in prison for the murder of a gay acquaintance.

Homosexuality was decriminalized in Russia in 1993. In 1999 it finally was excluded from Russian official list of mental illnesses. The change in people’s mind is still yet to come.

This article was originally published on 6 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

15 Oct 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Pakistan

Pakistan’s move to ban access to a gay website reflects the conservative society’s inability to accept a “larger world view”, activists say.

“Freedom of speech remains in peril and online privacy and security is almost nonexistent in the country making dissidents worry for their and their families’ safety”, Nighat Dad, a lawyer working with the Digital Rights Foundation in Pakistan, said.

Dad was referring to last month’s blocking of a gay website www.queerpk.com by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority for being “against Islam”.

But for others belonging to the LGBTQ community, the ban has not come as a big surprise.

“They banned YouTube, you think Queerpk would count at all?” said banker Imran, requesting only his first name to be used.

“It was quite expected and shows how immature this society is and how our government is keen on pandering to the idiocies of the worst among us”, said Ali (also preferring to use just his first name).

Kashif Khan, a gay university teacher, considers the website ban “just the tip of the iceberg” of a certain “mindset” that holds sway within the Pakistani society.

“We, as minorities, are not the only one affected by this heightened sense of self righteousness and religiosity which stems from this complete inability to entertain and appreciate any world view other than our own,” he said.

Further, he points out: “The closing of the mind and quashing of this spirit of inquiry is probably because a lot of beliefs that we have held sacred might not stand the test of rationality and empirical evidence.”

But Ali, for one, does not think it was a great idea for a group of LGBTQ community to try and create a space a space for themselves in public domain.

“Gay people here do not want a gay rights movement because this society isn’t the kind of society in which a gay rights movement can take place,” he said.

For too long, the LGBTQ community has remained invisible. They continue to enjoy both peace and relative freedom, but many fear that the moment they try to rock the boat and start demanding their rights, they may invite the attention of the religious extremist elements within society -much to their detriment.

Even the Pakistani law refuses to take a tolerant view of their existence. Article 377 of the Pakistan Penal Code prescribes up to 10 years in jail and a fine for those caught engaged in homosexual activity. Consenting sex between a man and a woman outside of marriage is criminalised and punishment awarded.

On the other hand, safeguarding citizens’ privacy is enshrined in Pakistan’s constitution, which calls “privacy rights” inviolable.

It is for that very reason Shahzad Ahmad, country director of Bytes For All, Pakistan, says that the Pakistani society “first acknowledge and recognise that the LGBTQ community exists”. It is also important, he said, to give more space to such portals where the gay community can discuss their issues in a “mature, understandable and engaging way”.

Even for Queerpk team the ban was not unexpected “given the backlash the website had received online and ‘reporting’ to PTA”. The team was prepared with a Plan B. “We mirrored the website onto a new domain, routing all traffic to the new website,” the website’s spokesperson (who didn’t want his name to be made public) wrote in an email exchange.

In addition, the website ban has not affected the netizens visiting the website in any way: “It hasn’t! If anything, it has brought together several thousand more users, hundreds of whom have written to us in appreciation and support, many of whom were not connected to any support online or offline. So for all reasons, the blockade has worked in our favour,” the spokesperson added.

When it comes to freedom of expression, Pakistan is not the most generous of countries. Freedom House’s annual report Freedom on the Net 2013 put Pakistan among the top ten countries where internet and digital media freedom is curbed.

“The recent ban of Pakistani gay websites is a clear sign that the new government is following what the past governments have been doing in Pakistan,” Dad said.

According to Ahmad the government’s “moral policing policy” curbs alternate and progressive discourse was the reason behind the blockade of Queerpk. This is not the first time that gay websites have been targeted, he explains: “I remember, another LGBTQ social networking website ManJam was banned in Pakistan and that ban still exists for Pakistani users.”

Currently there are over a dozen dating and social networking websites aimed at the Pakistani LGBTQ community. But the case of QueerpK is different, say experts, because it was more than a networking website. “Many important and relevant issues were being discussed on the website and an alternate discourse on sexual minorities’ rights was, for the first time, discussed in a very mature manner in a conservative society like Pakistan,” said Ahmad.

“With the government’s internet censorship policies over last few years it is quite evident that this new medium for communication for LGBTQ community won’t last long,” he added.

For that reason, BFA feels compelled to work with different international organisations in support of Queerpk to voice its concern against the ban. “We have also raised this issue at different forums and are also planning to raise it at the Internet Governance Forum,” Shahzad told Index.

This article was originally posted on 15 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org