Erica Jong: Literature’s sexual rebels

(Photo: Erica Jong)

There have always been sexual rebels.

In the 18th century, Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter, Mary Shelley, were fiercely rebellious about sexuality. They also were great feminists. In the 20th century, Emma Goldman spoke for women who believed love should be free.

Our age tends to divide things by decades and generalise about them. So, it’s assumed that the 70s and the second wave of feminism introduced sexual freedom to women. This is absolutely not true. If you read The Group by Mary McCarthy (1963), Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller (1934), or Ulysses by James Joyce (1922), you see that sexual rebels have always been with us.

What was different about [my 1973 novel] Fear of Flying was that it was a book that tried to reveal how women thought about sex in an age when most books about women didn’t show this. So, when the book came out both women and men were shocked. Some said: “Women don’t think like this!” and some said: “Thank God, somebody is talking about how women really think!” What was fascinating to me as an author was how contradictory the responses were.

I always wanted to write the books for women that did not exist. There is a huge gap between what we write about and what we think about. I wanted to rip the top of the head off a lusty woman and expose her fantasies to the light. Fantasies are important but they don’t necessarily have to become realities. The zipless fuck was a fantasy of perfect idealized sex with a stranger, but it is often impossible to fulfill. Many readers missed that.

Now I see woman writers writing about bondage and discipline, cruelty and submission, and I wonder whether that is fantasy too. I’ve never been much interested in submission, so I read these books as fairytale fantasies for women.

I think it’s important not to take literature literally. We turn to writers to document our dream lives. We turn to writers to show us what we are afraid to show ourselves. Many writers who become known for sexuality are not that different from you and me. They have a need to reveal the unconscious mind. If we take them literally, we miss the point.

The big change in sexual writing happened in the 1960’s when books like Lolita and Tropic of Cancer were liberated by the courts. The change in literature emerged from the change in the law. Male writers got very excited and produced books like John Updike’s Couples (1968) and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint (1969). Suddenly it was possible to publish these very honest works. I wanted to show honesty from a woman’s point of view. I was not advocating a kind of behavior, but many people did not understand that.

In Fear of Dying, I have also been attempting to reveal something unrevealed before. An editor once told me there had never been a bestseller about a woman over 40. But as I watched women growing older, still feeling sexy, looking for a way to overcome mortality, I realised that we needed new books that showed how women had changed.

Like Fear of Flying, Fear of Dying is such a book.

Erica Jong is a novelist whose works include Fear of Flying and the newly-published Fear of Dying. (Her books are available on Amazon, iTunes, Waterstones or your local independent bookshop.)

This article was originally published on FeedYourNeedtoRead.com and is reposted here with permission.

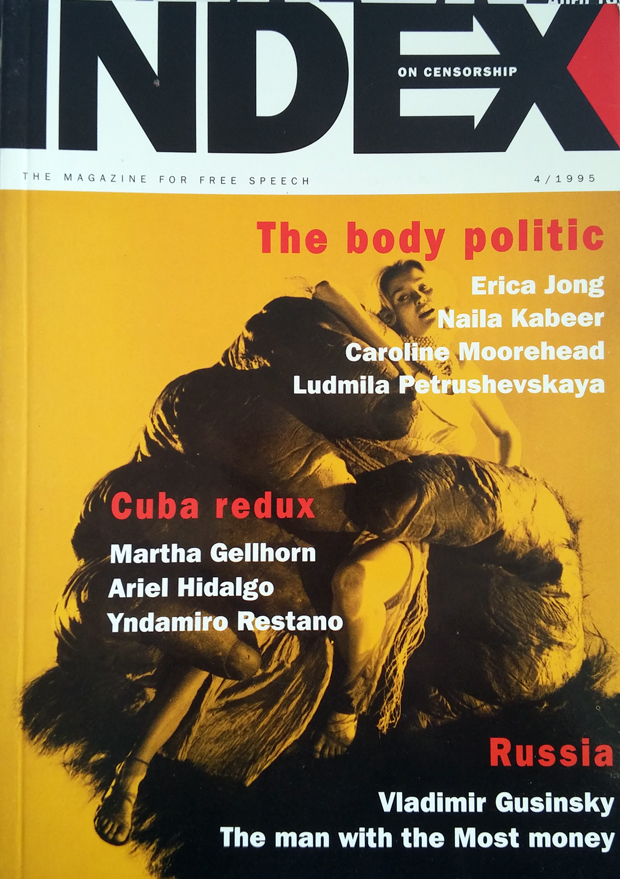

Erica Jong wrote for the summer 1995 issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Subscribe to the magazine. From the summer 1995 Index on Censorship magazine Erica Jong explains why pornography is to art as prudery is to the censors Pornographic material has been present in the art and literature of every society in every historical period. What has changed from epoch to epoch – or even from one decade to another – is the ability of such material to flourish publicly and to be distributed legally. After nearly 100 years of agitating for freedom to publish, we find that the enemies of freedom have multiplied, rather than diminished. |