11 Jul 2014 | Africa, News

(Photo: Zone 9/Facebook)

“We blog because we care!” This is the slogan and rallying cry of Zone 9, a group of young Ethiopians writing about social and political issues in their country. For over two months however, blogging has been out of the question for most of them. In late April, six members of the group – which takes its name from an area of Addis Ababa’s notorious Kaliti prison, where several journalists are jailed – were arrested and have been detained since.

Befeqadu Hailu, Abel Wabela, Atnaf Berahane, Natnael Feleke, Mahlet Fantahun, Zelalem Kibret – all between the age of 25 and 32 – have been accused of “working with foreign organisations” and “receiving finance to incite public violence through social media”, but have yet to be formally charged. Journalists Edom Kassaye, Tesfalem Weldeyes and Asemamaw Hailegiorgis were also arrested for their alleged links to Zone 9. Tomorrow, several of them are due in court again.

The story of the case so far, as covered by the blog Justice Matters, makes for worrying reading. The group were initially taken to Maekelawi detention centre, where according to Human Rights Watch, political prisoners have been tortured. They have been prevented from communicating with lawyers and family members. Hearings have predominantly served to extend the police’s investigation period. Police have also appeared to move away from accusing them of conspiring with foreign organisations and towards a terrorism charge, under which other journalists have been sentenced.

Zone 9 have been active since May 2012 and this is not the first time the group has attracted the attention of the authorities. According to their Facebook page, their mission is to provide an “alternative independent narration of the socio-political conditions in Ethiopia and thereby foster public discourse that will result in emergence of ideas for the betterment of the Nation”. They have organised online campaigns, including #EthiopianDream, encouraging their fellow citizens to share messages “question[ing] themselves and discuss[ing] their dream for the country”.

Their work has proved unpopular with the government of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn, who came to power following the death of long-time leader Meles Zenawi in 2012. The country’s leadership has continuously come under international criticism for its abysmal record on free expression and other human rights.

The majority of media is state-controlled or sympathetic to the government, with critical news outlets and journalists routinely targeted. Ethiopia is the world’s third worst jailer of the press, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. The sweeping anti-terrorism legislation put in place in 2009 is often utilised to crack down on oppositional voices. Journalist Eskinder Nega publicly questioned the law and its implementation, only to be convicted to 18 years in prison under it in 2012.

Beyond crackdowns on press freedom, the country’s Muslim community has been hounded by the government, opposition protests are regularly banned, and foreign NGOs are not allowed to work on political and human rights issues.

Zone 9 was set up against this backdrop, and the group soon discovered the, too, were seen as a threat. The blog has been blocked and members have faced harassed at the hands of security services. Last September they took what would end up being a seven-month hiatus from publishing, due to the pressures connected to running the site. The six were arrested only days after announcing that they were to resume blogging.

Despite the fact that internet penetration in Ethiopia currently stands at around 1 per cent, authorities seems very aware of the web’s potential as a platform for free expression and, in turn, dissent. Paul Brown of BBC Monitoring believes the Zone 9 arrests “suggest that the government is taking online activism seriously – probably because elections are due next year.” There have even been reports of the government “training” internet users to post attacks on those who criticise authorities online and to post messages of support for the regime.

Zone 9 co-founder Endalkachew H/Michael recently spoke to CPJ from New York; he left Ethiopia to study in the US shortly before his colleagues were arrested. He says the government are trying to control the flow of information. “There is no plurality of voices in government and media. And they want to control that because there is a sort of plurality on the internet. If you go into the Ethiopian social media sphere, you see all kinds of comments about the government and opposition groups,” he explains.

The government, meanwhile, has denied any wrongdoing, saying the arrests are not connected to journalism but “serious criminal activity”.

“We don’t crack down on journalism or freedom of speech. But if someone tries to use his or her profession to engage in criminal activities, then there is a distinction there,” Getachew Reda, an adviser to the prime minister told Reuters.

But the story has drawn widespread condemnation, from international human rights organisations to news outlets to diplomats, with even US Secretary of State John Kerry calling it a “serious issue”. The hashtag #FreeZone9Bloggers has in the past few weeks accumulated outrage and solidarity from across the world. Endalkachew H/Michael says this attention in important. “I want the public to remain focused on this issue. The government is trying to make the public forget the human rights violations and journalists’ poor situation in Ethiopia.”

UPDATE 12 JUNE

According to Endalkachew H/Michael, following today’s hearing the case has been referred to a federal high court. The accused were reportedly not present for the hearing.

This article was posted on July 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Jul 2014 | Germany, Mapping Media Freedom, News

A local newspaper in the western German city of Darmstadt is at the centre of a legal case that will measure whether readers’ comments are protected by Germany’s press freedom laws.

On June 24, police and the Darmstadt public prosecutor arrived with a search warrant at the offices of the newspaper Echo. A complaint had been filed over a 2013 reader comment on Echo’s website. Months later, a local court issued a search warrant to force the newspaper to hand over the commenter’s user data.

The comment, which was left under the username “Tinker” on an article about construction work in a town near Darmstadt, questioned the intelligence of two public officials there. Within hours, Echo had removed the comment from its website after finding that it did not comply with its policy for reader comments. According to a statement Echo released after the June confrontation with police, the two town administrators named in the comment had filed the complaint, alleging that it was insulting. This January, Darmstadt police sent the newspaper a written request for the commenter’s user data. Echo declined.

When police showed up at Echo’s offices five months after their initial request for the commenter’s identity, the newspaper’s publisher gave them the user data, preventing a search of Echo’s offices. A representative for the Darmstadt public prosecutor later defended the warrant.

“It’s our opinion that the comment does not fall under press freedom because we assume that the editorial staff doesn’t edit the comments,” Noah Krüger, a representative for the Darmstadt public prosecutor, told Echo.

According to Hannes Fischer, a spokesperson for Echo, the newspaper is preparing legal action against the search warrant.

“We see this as a clear intervention in press freedom,” Fischer said. “Comments are part of editorial content because we use them for reporting – to see what people are saying. So we see every comment on our website as clearly part of our editorial content, and they therefore are to be protected as sources.”

In early 2013, a search warrant was used against the southern German newspaper Die Augsburger Allgemeine to retrieve user data for a commenter on the newspaper’s website. In that case, a local public official had also filed a complaint over a comment he found insulting. The newspaper appealed the case and an Augsburg court ruled that the search warrant was illegal. The court rejected the official’s complaint that the comment was insulting, but also ruled against Die Augsburger Allgemeine’s claim that user comments are protected under press freedom laws.

In Echo’s case, the commenter’s freedom of speech will likely be considered in determining whether the comment was insulting. If convicted of insult, the commenter could face a fine or prison sentence of up to one year. Given the precedent from the 2013 case and the public prosecutor’s response, it’s unclear whether press freedom laws may be considered against the search warrant. Ulrich Janßen, president of the German Journalists’ Union (dju), agreed that user comments should be protected by press freedom laws. “If the editors removed the comment, then that’s a form of editing. That speaks against the argument that comments are not editorial content,” Janßen said. Warning that the search warrant against Echo may lead to intimidation of media, Janßen cautioned, “Self-censorship could result when state authorities don’t respect press freedom of editorial content.”

Recent reports from Germany via mediafreedom.ushahidi.com:

Court rules 2011 confiscation of podcasters’ equipment was illegal

New publisher of tabloid to lay off three quarters of employees

Police use search warrant against newspaper to obtain website commenter’s data

Blogger covering court case faced with interim injunction

Competing local newspapers share content, threatening press diversity

Transparency platform wins court case against Ministry of the Interior

This article was posted on July 11, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

9 Jul 2014 | Campaigns, Press Releases

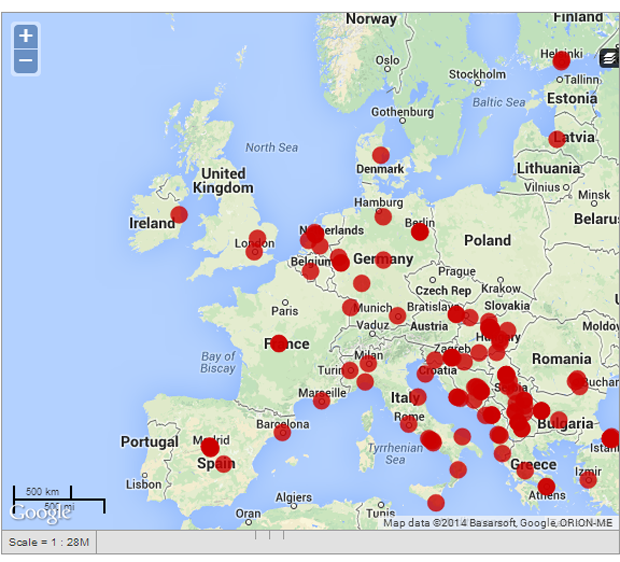

Over 170 cases have been submitted on a new media freedom crowdsourcing platform since its launch in May, while about half of the mapped cases of censorship and violations that spread in all 28 EU member states and candidate countries occurred in southern and southeast Europe.

Mediafreedom.ushahidi.com is a website that enables media professionals and citizen journalists to report and map media freedom violations across the 28 EU member states plus candidate countries. Ushahidi means ‘testimony’ in Swahili. Single cases can be uploaded through direct reporting on the platform or sent via email and be visualised on a Google map.

Information on the map reveals some common trends and similar problems across the region.

Over 40 of the reported cases involve legal measures taken against a journalist or a media, suggesting the pressing need of legal support and protection of those affect. Despite the existence of several associations and NGOs offering such support, journalists often fail to get the help they need on time, if ever.

Meanwhile arrests, verbal and physical attacks continue to be used as a tool to scare or discredit professionals. In some cases, journalists are detained in the field without clear explanation or warrant only to be released several hours later, when they can no longer report the event they originally intended.

A high concentration of violations is observed in Turkey, Italy and Serbia.

In Turkey, where 17 cases have been reported, financial and legal pressure seems to be one of the main tools used to silence critical voices.

In Serbia, where 16 cases have been reported, May’s devastating floods unleashed a series of worrying developments that made the international and local community turn their eyes towards the state of media freedom and spreading censorship in the country. For instance, several blogs experienced blockades and attacks after criticizing the government’s role and reaction to the floods.

In Italy 15 cases have been reported, with many involving threats and assault.

About the project

The Ushahidi media freedom crowd-sourcing platform has been developed in partnership by Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso and Index on Censorship. OBC participates in the initiative as part of the EU-funded Safety Net for European Journalists project, implemented in partnership with SEEMO, Ossigeno Informazione, Professor Eugenia Siapera (Dublin City University).

For more information please contact:

[email protected]

[email protected]

26 Jun 2014 | Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan News, News

The Baku Court of Grave Crimes announced the verdict for the NIDA movement activists in May 2014. The human rights defenders Rashadat Akhundov, Zaur Gurbanly and Ilkin Rustamzadeh to 8 years’ imprisonment, Rashad Hasanov and Mamed Azizov – to 7.5 years. Protesters were detained and victimised by police. (Photo: Aziz Karimov / Demotix)

In a bleakly comic turn at the beginning of Ilham Aliyev’s address to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe this week, Assembly president Anne Brasseur asked press photographers to leave the chamber and reminded those present that they were not permitted to vocalise their approval or disapproval during the Azerbaijani dictator’s stand. It appeared that Brasseur hadn’t quite meant what she said, as in the end photographers at the front of the room were merely required to move their tripods to ensure everyone in the room could see Aliyev as he spoke.

Aliyev’s speech was given to mark the Azerbaijan’s taking up of the chair of the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers last month. And what a speech it was!

The man who promises to “turn initiatives into reality” (still no idea) told of Azerbaijan’s enormous progress in all fields, not just oil fields. He spoke of the country’s “very positive atmosphere” and listed the country’s great freedoms: freedom of political activity, freedom of expression, freedom of media… Azerbaijan was proud of these freedoms, he said. Azerbaijan knew that an uncensored internet and independent newspapers were important for democracy.

It was a lovely speech, and also one that contained barely a word of truth beyond the conjunctions. Aliyev may as well have praised the nation’s Quidditch team for defeating Ravenclaw on penalties at the World Cup. He could have told us about his new motorcar, and his adventures with Ratty, Mole and Badger, and been more believable.

Watching Aliyev, the only time one got the sense he even believed what he was saying himself was when discussing the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, and even then he was only drily insisting that the regions “geographical toponyms” (place names?) were Azeri in origin: All Your Geographical Toponyms Are Belong To Us, so to speak.

The truth about Azerbaijan is quite different from the picture painted by its president this week. As Human Rights Watch pointed out ahead of the Council of Europe speech, “In the past two years, Azerbaijani authorities have brought or threatened unfounded criminal charges against at least 40 political activists, journalists, bloggers, and human rights defenders, most of whom are behind bars.” Search for Azerbaijan stories on Index, and you will find more details of those arrests and abuses.

And this isn’t exactly obscure knowledge. People know three things about Azerbaijan: it has a lot of gas and oil; it takes Eurovision very seriously; and it has a poor human rights record. After his speech, Aliyev was confronted by Michael McNamara of the CoE socialist group, who quoted Amnesty’s statistic that there are currently 19 political prisoners in Azerbaijan. Not so, said Aliyev. There are no political prisoners in Azerbaijan. The people who came up with these statistics were lying. There was a programme of “deliberate provocation” against Azerbaijan — though it was unspecified who was leading this programme.

Aliyev swore that this plot to undermine Azerbaijan would fail.

The Azerbaijani president is not alone in his capability for bare-faced falsehood. It’s a specific strain of Soviet and post-Soviet behaviour, learned from the Communist Party and the KGB. If the leader says something, it is true, no matter what the evidence to the contrary. There are no political prisoners in Azerbaijan, says Aliyev, and we encourage a free media because it is important to our democracy; Ukraine has been taken over by fascists, says Vladimir Putin, and Russia has no choice but to fight them. There is no point in putting on a play about depression in Belarus, an Alexander Lukashenko apparatchik tells the Belarus Free Theatre, because there is no such thing as depression in Belarus.

“So what?” you may say. “Politicians and institutions lie.” And you’d be right. But this is a form of lying that goes far beyond “I was perfectly within my rights to claim those expenses”/”I did not have sex with that woman”. Political lies in functioning democracies tend to have to do with cover ups of personal or institutional failings. In an authoritarian society, with power utterly concentrated to the leader and his cadre, there is no such thing as an isolated failure. As a result, every aspect of life must be spun. All triumphs belong to the leader, all criticisms are propaganda, all failures sabotage. When there is no balance of power, is there really an objective truth? When, for example, the dictator Lukashenko told a journalist that journalist Irina Khalip, under house arrest, could leave Belarus any time she wanted, was that actually true? Was it true the moment he said it? Did it become true after he said it? And did it remain true?

This state of things raises a question for those of us seeking to better the lot of people living under regimes such as Belarus and Azerbaijan: can we pounce on the moments when autocrats declare as fact something we know to be untrue, cling on until they actually make it true? Or does this merely confirm the idea that truth is whatever their whim makes it?

This article was posted on June 26, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org