Groups condemn removal of police protest painting from US Capitol

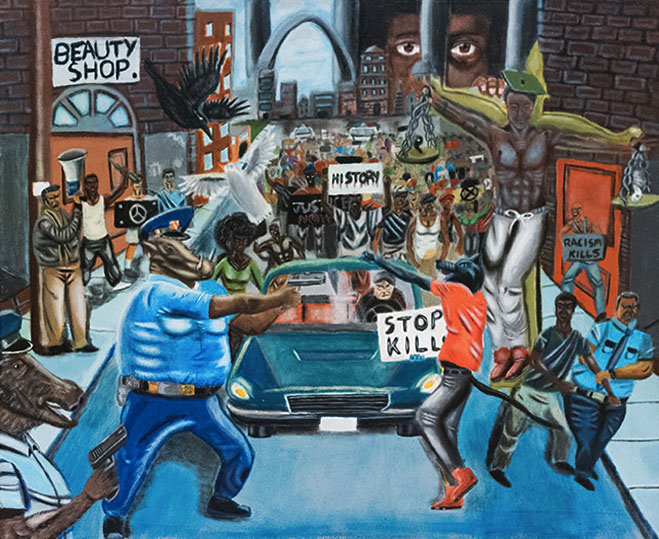

Untitled #1, by David Pulphus

As organisations devoted to promoting the arts and freedom of expression, we condemn the recent removal of a student painting from a public passageway on Capitol Hill. The removal shows a deep disregard of a young person’s constitutional right to free expression and is a flagrant violation of the principles underlying the nation’s commitment to the protection of free speech. It is a sad day when elected representatives of the people of the United States send a message to young people in this country that they should stifle passionate expression concerning important issues of public policy.

The painting, by St. Louis High School Senior David Pulphus, is among the winners of the annual Congressional Art Competition. It depicts, in an allegorical manner, a young artist’s vision of one of the facts of our recent past: a protest against police violence. Pulphus’ painting was selected through a process set by the Competition, which included a review by the office of the Architect of the Capitol. It was approved and remained on display for six months until conservative news outlets built up a controversy around it in late December.

The media-generated controversy was followed by multiple attempts on the part of several Republican Representatives to take down the work with their own hands (each time, Representative Clay (D-Mo) put it back up). On Friday, January 13th, Stephen Ayers, the Architect of the Capitol, ordered the painting’s removal on the basis that it violated competition guidelines stipulating that “subjects of contemporary political controversy or a sensationalistic or gruesome nature are not allowed.”

The retroactive use of the very guidelines by which the painting was selected in the first place to remove the work only serves to draw attention to the how vague these guidelines are. Worse, the fact that the decision to censor the work was made under strong political pressure coming from one side of the aisle proves how easy it is to use the vague guidelines to suppress political viewpoints.

What is “controversial” is entirely subjective and thus open to abuse and the enforcement of political bias: Indeed, many other artworks in the exhibition may be deemed controversial, including a depiction of white police officers harassing an African American playing checkers, a portrait of Bernie Sanders and another of President Obama. And, of course, portraits and statuary on permanent display in Congressional buildings represent many political figures that are controversial. That Pulphus’ painting of police protests was singled out among all these for a hasty removal, after partisan political pressure by representatives who claimed the work was offensive to law enforcement, only deepens our concerns about the elected representatives enforcing political bias and stifling speech.

Political artistic expression is protected speech, no matter how controversial or offensive some may find it. Criticism of government actors such as law enforcement officials is one of the foremost reasons why we have the First Amendment. Citizens’ freedom to speak out against perceived governmental abuses and injustices is necessary to the health of our democracy: were government able to silence such criticisms, meaningful political discourse would be rendered impossible.

Removing the work sends a message to young people – and everybody else – that they should not depict the world around them for fear of offending our political representatives. At a time when we have a new administration and nationwide concerns about free speech, the censoring of an artwork because of its viewpoint is a deeply disturbing and divisive act in an already polarised nation.

We urge the Architect of the Capitol to take the time to consider arguments from both sides of the aisle and make a decision that upholds one of the nation’s most cherished values, a value that should not be subject to partisan strife: the value of free speech. We hope that rather than exacerbating partisan conflict, the controversy around this young person’s painting becomes a unifying educational opportunity to reinforce free speech principles across both sides of the aisle.

National Coalition Against Censorship

American Civil Liberties Union

American Civil Liberties Union of the District of Columbia

American Society of Journalists and Authors

Authors Guild

College Art Association

Comic Book Legal Defense Fund

Free Speech Coalition

Index on Censorship

PEN America

Vera List Center for Art and Politics

Washington Area Lawyers for the Arts