5 Feb 2015 | mobile, News, United Kingdom

Joshua Bonehill (Wikipedia user JoshuaBonehill92)

Joshua Bonehill is a national socialist, in an almost refreshingly old-fashioned way. When young Joshua speaks out against those who are destroying-our-society, undermining-our-culture, and so on, he does not equivocate with “neo-cons”, “internationalists” “bankers” or “global finance”. No, dear young Joshua comes straight out and says he’s against Jews (sometimes “the Jew”).

Bonehill hit the news this week after he said he would organise a march in Stamford Hill, north-east London on 22 March. Bonehill says his march is against the “Jewification” of Stamford Hill, to which one is tempted to answer “bit late, Joshua”. Stamford Hill is home to roughly 30,000 ultra-Orthodox Jewish people, mostly of the Haredi persuasion.

Bonehill is a keyboard Führer, an online agitator. His most notable “success” so far in his activist life has been spreading a false story about a pub in Leicester refusing to serve people in military uniform. The pub received threats of firebombing. Bonehill was convicted of malicious communications, though he escaped jail. He has a court appearance for similar offences lined up next week, and could quite conceivably go to prison for them, which would be a severe blow to his chances of rallying in Stamford Hill.

This hasn’t stopped a certain level of excitement spreading through social media (and indeed traditional media). Leftist and leftish friends on Facebook and Twitter have been excitedly discussing the prospect of Bonehill turning up on Clapton Common with hundreds of goons ready to make the borough of Hackney Judenfrei. In spite of his non-existent real world base, there is a very, very slight possibility that Bonehill could get more than a half-dozen. The Guardian points out that Bonehill has over 26,000 Twitter followers, “raising fears that even without a genuine political organisation behind him, his plan could draw in other far-right groups …”. To put that in slight perspective, I have a quarter of that number of Twitter followers, and can’t even muster people for an after work drink on a Friday evening, but then, I suppose I’m not trying to make a grab for the leadership of a scene that has been a mess since the collapse of the British National Party’s vote in the last European and local elections.

That is what Bonehill is getting at here. In his promotional YouTube videos for his march, he repeatedly calls for unity among “nationalists”. By targeting a Jewish area, he is hoping to rally the hardcore of British nationalism to his side; fascism’s attempt at populism, under Nick Griffin, had its thunder stolen by Ukip, and the hard core needs the reassurance of conspiracy theory and naked anti-Semitism.

Bonehill also appeals to his fellow racists’ sense of history, invoking the famous Battle of Cable Street, in which Oswald Mosley led the British Union of Fascists into (then Jewish area) Whitechapel and was met by local opposition from Jews, trades unionists and communists. Bonehill describes the 1936 rally as a “glorious victory”, which will come as a surprise to most leftists for whom Cable Street is shorthand for left virtue. (The Times’s Oliver Kamm has an interesting take on this.)

The memory of Cable Street is obviously looming large in the imagination of leftists and anti-fascists steeling themselves to organise against Bonehill. Cable Street is the universal good that everyone on the fractious left can share, and some would probably like to reenact it in some way in Stamford Hill, without necessarily working with the Jewish groups such as the Community Security Trust and the Shomrim, a community group Bonehill wrongly describes as a “Jewish Police Force”.

Cable Street was not the only time Mosley attempted to march in east London. Much later, in 1962, Mosley and his son Max (yes, that Max Mosley) were driven from the streets in Dalston, not far from Stamford Hill (watch this fantastic Pathe News footage).

So what is this then? Cable Street? Dalston? Even Skokie, Illinois, where the American Civil Liberties Union stood for the right of the American Nazi Party to march through a town populated by many Holocaust survivors (that march, in the end, never went ahead, but the position taken by the ACLU is often presented as a paragon of free speech principle, or bloodymindedness, or foolhardiness, depending who you talk to).

Bonehill has appealed to “the free speech community”– I’m guessing that’s you and me, dear reader – to stand with him, because “the Jews want us silenced” and his proposed protest has become “a battleground for free speech”. This is, of course, tosh. It is idiotic to conflate the support of free speech with the support of what people are saying. But that does not mean we could sit back and ignore this.

It would be wrong if Bonehill’s planned demonstration was banned in advance. Wrong because unpleasant though he is, he does have a right to protest and face counter protest (as did say, the EDL in areas with high Muslim populations), and wrong because it may lend a small bit of credibility to a deluded clown who may well be in jail by the time the appointed date comes round.

This column was posted on February 5, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

13 Nov 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Politics and Society, Russia, United Kingdom

(Photo: Padraig Reidy)

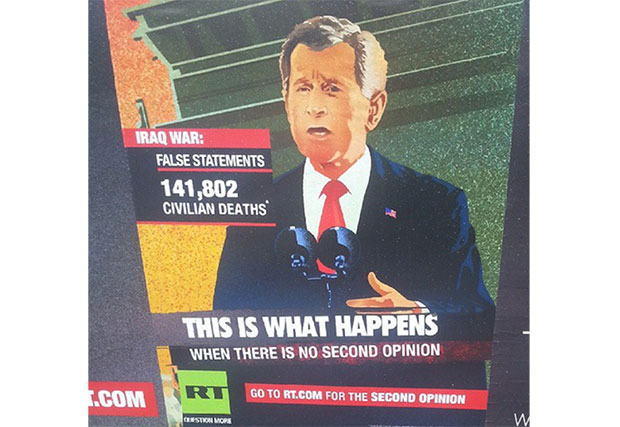

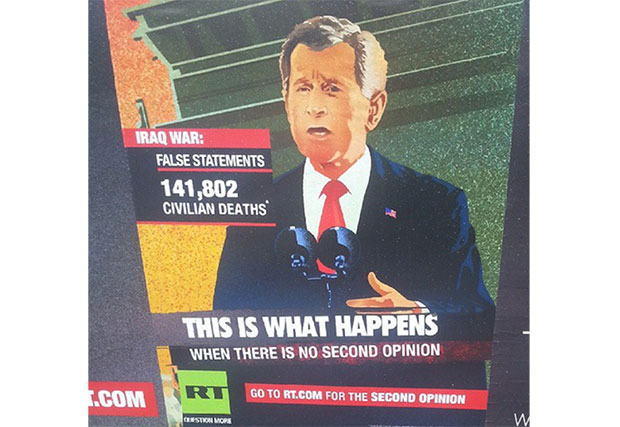

There’s a poster near my house in London. It shows a poorly illustrated George W. Bush, aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln early in the Iraq war, with the now infamous “Mission Accomplished” banner behind him. To his side, the tally of dead in the Iraq War (at least according to Iraq Body Count). Underneath is emblazoned the slogan: “This is what happens when there is no second opinion.” It is an advert for Russian propaganda channel RT (formerly Russia Today).

It’s a slightly muddled poster, but the signal is clear: did you feel lied to about the Iraq war? Watch RT.

Curiously, RT, which launched a UK channel on 30 October, seems to believe the poster doesn’t exist. A “report” on the RT website, dated 9 October, claims that the campaign of which this poster is part was “rejected for outdoor displays in London because of their ‘political overtones’”. The story goes on to claim that the “rejected” posters were replaced by ones that simply say “redacted”, before urging readers to download an RT app to view the ads on their phones.

But I have seen the poster. I even took a picture. Yet RT insists it has been banned, saying that outdoor advertising companies cited the Communications Act 2003, which “prohibits political advertising”. This prohibition is indeed to be found in the act, but only applies to broadcast advertisements, not billboard advertisements for broadcasters.

This is a fairly crude illustration of RT’s attitude to the truth. It is simply not an issue. What’s important is something that might sound true, something just about plausible, to suit the agenda (in this case, the agenda is threefold: one, to get people to download the app; two, to sow the belief that “they” are scared of RT; and three, to introduce the notion that political advertising is subject to a blanket ban in the UK).

Fair enough, you might say. But have you seen Fox News? Don’t all sorts of news organisations bend the truth to fit their agenda? There’s a case to be made, but there’s also a crucial difference. RT is funded and controlled by the Kremlin and is on a mission; a mission outlined in a new report by The Interpreter, part of the Institute of Modern Russia (disclosure: Index on Censorship has on occassion crossposted content from The Interpreter).

“The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money” elucidates what we had already long suspected: the Soviet Union may be dead, but Soviet tactics remain. And while the west may not want to believe it is in conflict with Russia, the Russians are already acting like it is (witness reports of heightened Russian air force activity in and near Nato airspace).

The report’s authors, Michael Weiss and Peter Pomerantsev, describe disinformation techniques dating back to the Soviet era: straight propaganda, certainly, but also Dezinformatsiya — the planting of false stories to undermine confidence in western governments. These include alleged coup plots, the bizarre theory that AIDS was created by the CIA, even the suggestion that the assassination of Kennedy was an inside job.

The suggestion is that democracy is a sham, and that democratic governments are at best hypocrites and at worst constantly, deliberately acting against the interests of their own populations.

The best false stories always have a ring of truth and a ring of empathy. Many politicians are hypocrites, some politicians act against the interests of those they should represent. If this much is true, is it that much of a leap to imagine that the entire system is a crock? That democracy and human rights are empty terms? We’re just asking legitimate questions, as every conspiracy theorist ever has said at some point.

Conspiracy theorists find a home at RT. Presenter Abby Martin, for example, who briefly won praise for apparently criticising Russia’s actions in Ukraine, says she still has “many questions” (just asking questions!) about the September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center, and has used her show to expound on “false flag” attacks, alleged Israeli eugenics, and every US conspiracy theorists’ favourite, the massacre in Waco, Texas of David Koresh’s Branch Davidian cult in 1993.

All this would mean nothing if RT didn’t have a willing audience in the UK, the US and beyond. But a combination of a large budget, photogenic presenters and a certain way with a YouTube clip makes RT a serious player. It never quite veers into the straight out lunacy of Iran’s Press TV, which is quite open about its conspiracist contributors, and it looks like a serious operation. Furthermore, its positioning as an “alternative news source”, albeit one controlled by an increasingly authoritarian, paranoid and erratic Russian state, finds it fans among people who would rail against their own liberal states and societies (on the two occasions I visited the Occupy St Paul’s encampment in London, Russia Today was playing on a large screen there). All the while, the autocratic Putin is strengthened as democracy in undermined worldwide (witness how easily Putin was able to put the kibosh on effective intervention against Syria’s Assad through the relentless repetition of the line that helping the opposition would mean helping jihadist terrorists).

So what, as Lenin himself once asked, is to be done? After reports of UK broadcast regulator Ofcom’s recent investigations into RT for bias earlier this week, some people saw a chance to get RT taken off the air just weeks after it had begun. But this impulse is too close to political censorship in principle, and in practice, an ineffective sanction against a force that has huge power online, with millions upon millions of YouTube hits.

Decent democrats that they are, Weiss and Pomerantsev suggest eternal vigilance is required: we must be able to combat RT’s half truths and insinuations effectively, with hard facts and hard arguments, in order to stop them spreading. As ever, when arguments for counterspeech as the best defence against poison is suggested, one remembers Yeats’s lines: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/Are full of passionate intensity.”

But this time 25 years ago, as East and West Germans embraced on top of the Berlin Wall, the world showed that the right argument can win even against the very worst. The Kremlin is playing the same games now as it did in its darkest days. Democrats should be ready to fight back.

This article was posted on 13 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

6 Nov 2014 | News, Politics and Society

![People taking part in the funeral procession of Lasantha Wickrematunge (By Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Lasantha_Wickrematunge_funeral_banners_1.jpg)

People taking part in the funeral procession of murdered journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge (Photo by: Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

This would be no defence for Lasantha. President Mahinda Rajapaksa repeatedly referred to him as a “terrorist journalist” and “Kotiyek” (a Tiger).

According to exiled journalist Uvindu Kurukulasuriya, shortly before Lasantha was killed, the president offered to buy the Sunday Leader, with the intention of muting its voice. Lasantha declined the generous offer. On 8 January 2009, he was shot dead.

Days later, an astonishing editorial, written by Lasantha before his death, appeared in the Sunday Leader, and subsequently in newspapers throughout the world. After describing his pride in the Sunday Leader’s journalism, Wickrematunge wrote chillingly: “When finally I am killed, it will be the government that kills me.”

Lasantha’s murder was shocking. As was the murder of Hrant Dink, the Armenian editor who “insulted Turkishness” by daring to speak of the genocide of his people; as was the murder of Anastasia Barburova, the young Novaya Gazeta reporter who investigated the Russian far right; as was the murder of Martin O’Hagan, who took on the criminality of Northern Ireland’s loyalist gangs. As were the murders of the dozens of Filipino journalists killed in the Maguindanao massacre in 2009, too numerous to name, caught up in a ruthless turf war.

Then there are the reporters killed in war zones. The conflict in Syria has been a killing field for journalists. Where once the media were seen as protected, even potential allies, now they are seen as targets. The killings of Steven Sotloff and James Foley by ISIS in Iraq brought back memories of the beheading of Daniel Pearl in Pakistan in 2002. As Joel Simon of Committee to Protect Journalists relates in his forthcoming book, the New Censorship, that crime marked a turning point. In the Pearl case, even Osama bin Laden, who viewed the media as a potential tool in his global war, was shocked by the tactic employed by his lieutenant Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who claimed to have carried out the murder himself. From that point on, journalists were not just fair game, but trophies.

As money is drained from news, many organisations choose not to send correspondents to areas where reporters are needed most. Too dangerous, too expensive. As a result, freelancers, local journalists and fixers take ever greater risks. Under-resourced, undersupported and out on a limb, they are picked off.

Regional journalists covering tough domestic beats are easy prey. In Mexico, drug cartels boast of their ability to murder reporters. In Burma, the army kills a reporter who dares report its activities.

The numbers are horrifying: over 1,000 media workers have been killed because of their work since 1992.

Every single time, the message is sent: don’t get involved; don’t ask questions; don’t do your job. No journalism here. No inconvenient truths, no dissenting voices.

With rare exceptions, those responsible for these crimes act with impunity. Sometimes, as in the case of Anna Politkovskaya, outspoken on war crimes in Chechnya, the man who pulled the trigger is traced but those who gave the orders remain untouched. In over 90 per cent of cases of attacks on journalists, there are no convictions.

There is no greater infringement of human rights than to deliberately take an innocent life. The killing of a journalist also signals contempt for the concept of free expression as a right. As the United Nation’s Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, states, violent attacks on journalists and free expression do not happen in a vacuum: “[T]he existence of laws that curtail freedom of expression (e.g. overly restrictive defamation laws), must be addressed. The media industry also must deal with low wages and improving journalistic skills. To whatever extent possible, the public must be made aware of these challenges in the public and private spheres and the consequences from a failure to act.”

In that famous final editorial, Lasantha Wickrematunge wrote: “In the course of the last few years, the independent media have increasingly come under attack. Electronic and print institutions have been burned, bombed, sealed and coerced. Countless journalists have been harassed, threatened and killed. It has been my honour to belong to all those categories.”

Like many journalists, Lasantha prided himself on bravery: there is no higher compliment in the profession than to call a colleague “courageous”.

But there is a danger in this that we create martyrs: that we become enamoured of the idea that a good journalist should die for the cause. That persecution and suffering are marks of valour.

They are not. Journalism should be intrepid, of course, but we shouldn’t accept the idea that intrepid journalism comes with a price. Journalism, the exercise of free expression, is a basic right both for practitioners and for the readers, viewers and listeners who benifit from it. They should be able to practice this right without fear of persecution from states, criminals or terrorists. If they are to suffer, their oppressors must face justice.

Correction 10:02, 10 November: An earlier version of this article stated that a government minister offered to buy the Sunday Leader.

Index on Censorship is mapping harassment and violence against journalists across the European Union and candidate countries at mediafreedom.ushahidi.com.

This article was posted on 6 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

16 Oct 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Thirty years ago this week a bomb exploded in the Grand Hotel, Brighton, where the then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and much of her cabinet were staying during Conservative party conference.

The bomb had been planted a month previously by IRA member Patrick Magee, with the intention of assassinating the prime minister. Thatcher escaped, but others did not. Five party members died. Others, including Margaret Tebbit, wife of Thatcher’s rottweiller Norman Tebbit, were left disabled.

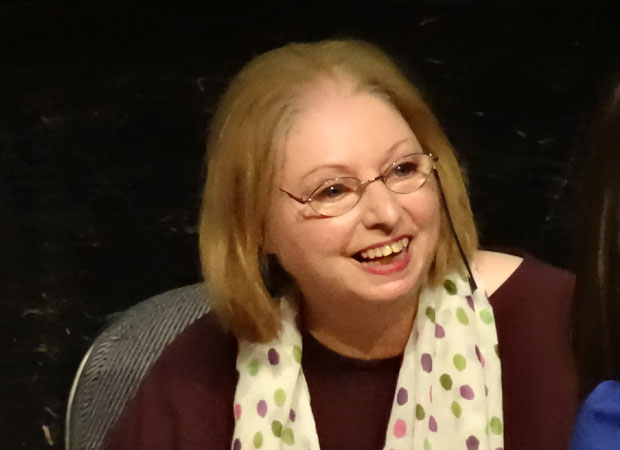

The whereabouts of then-32-year old aspiring novelist Hilary Mantel at the time were not known, but we do now know that she herself was thinking about killing Thatcher as the IRA was planning the Grand bombing.

Last week, at the Royal Festival Hall, a solid concrete building that looks as if it could survive the combined explosive attentions of the IRA, Al Qaeda and a reanimated Fred Dibnah, Mantel discussed her own Thatcher assassination plot, which was published this year in the form of a short story that she had started over 3 decades ago.

“People have worked so hard to take offence at this story,” the Wolf Hall author pointed out, adding mischievously, “If only they would go through my extensive back catalogue it would keep them in fury for the rest of their lives.”

Mantel’s assassination fantasy is an enjoyable piece of suburban noir in which an IRA sniper attempts to use a Windsor woman’s window as a hide to take a shot at Thatcher. It’s interesting in that one finds the narrator and the gunman jockeying for position about their right to revile Thatcher as they do: who is more Irish? who is more Northern? Who is more affected by this terrible woman?

But ultimately it’s an almost Tales-Of-The-Unexpectedish story about extraordinary things happening to ordinary people.

Mrs Thatcher’s friend Lord Bell was horrified by Mantel’s story and her subsequent interview in The Guardian, where Mantel described seeing Thatcher leaving the hospital in 1983, saying that “if I wasn’t me, if I was someone else, she’d be dead”. Lord Bell angrily announced: “If somebody admits they want to assassinate somebody, surely the police should investigate. This is in unquestionably bad taste.”

The Daily Mail’s Stephen Glover was equally apoplectic: “Mantel’s contribution is peculiarly damaging because, while she appears so mild-mannered, her message is interpretable as a deadly one. If you don’t like your democratically elected leaders, who operate within the rule of law, you can always think about assassinating them.”

What Bell and Glover both seem to have failed to grasp here is the difference between thinking about something and doing it, or even the difference between thinking about doing something and plotting to do it.

Thinking about doing things one would not normally do is often known as “imagining”, and is quite crucial to the creative process. It’s an essential part of humanity that we can think beyond ourselves. It’s what allows us to empathise and sympathise; we may not be familiar with a specific set of circumstances, but we can, at least in part, imagine what it would be like to be placed in certain circumstances. I have never been homeless, but I can imagine that I wouldn’t like it. I can even imagine what might go through the head of someone I profoundly disagree with.

It was by sheer coincidence that the night before Mantel spoke at the Royal Festival Hall, Salman Rushdie received the PEN Pinter prize at the British Library.

While Mrs Thatcher was still prime minister, Rushdie’s imagination got him into rare trouble when he published the allegedly “blasphemous” Satanic Verses. Whether the allegation of blasphemy was correct or not, is, by the way, irrelevant. That suggestion would not validate the non-publication of a book, and certainly would not justify the murder contract put out by the supreme leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, in February 1989.

Rushdie’s western critics then often couched their criticisms in terms that emphasised their empathy with the “Muslim anger” which gave rise to protests across the world and eventually the Ayatollah’s incitement to murder; they understood, they implied. They too, had been hurt. Mrs Thatcher herself (characterised as “Mrs Torture” in the book) said: “We have known in our religion people doing things which are deeply offensive to some of us and we have felt it very much.”

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, commented: “I well understand the devout Muslims’ reaction, wounded by what they hold most dear and would themselves die for.”

No mention of being able to well understand or even imagine what it might be like to be on the end of protests, to see your effigy burned in anger across the world.

In his speech at the British Library, Rushdie described one of the worst aspects of the onslaught against his imaginative work; the need to counteract the ignorant prescriptions of The Satanic Verses by those who wanted to have him censored and worse.

“Once the attack was fully underway,” said Rusdhie, “I felt obliged for a long time to fight back against the creation of that false version of The Satanic Verses by offering counter-explanations of my own. I loathed doing it, and often felt that by offering the almost line by line defence that seemed necessary I was damaging the kind of open, private reading of my novel for which, like every writer, I had hoped.”

After Rushdie spoke, a remarkable speech from International Writer of Courage winner Mazen Darwish was read out. Darwish, founder of the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression, is currently in a regime jail in Damascus, faced with charges of “publicicing terrorism”. He somehow managed to smuggle a letter to London.

Addressing Rushdie directly, he offered a startling apology for the inaction of many people in the Middle East at the time of the fatwa, saying their indifference was tantamount to collusion to murder.

Drawing a line between the censorship of 1989 and the rise of the Islamic State in Syria today, Darwish lamented: “What a shame this much blood has had to be spilled for us to realise, finally, that we are digging our own graves when we allow thought to be crushed by accusations of unbelief, calling people infidels, and when we allow opinion to be countered with violence.”

Not, bear in mind, the extrapolations of a north London liberal, but a man in prison who knows acutely the price of standing up for the individual, for empathy, and for free expression. Words to bear in mind the next time we’re tempted to embark on a collective outrage against words and thoughts and imagination itself.

This article was posted on 16 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![People taking part in the funeral procession of Lasantha Wickrematunge (By Indi Samarajiva [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Lasantha_Wickrematunge_funeral_banners_1.jpg)