25 May 2021 | News and features, United States

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116812″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]George Floyd was my dad. He was my brother and my cousin, and my boyfriend and my criminology professor, and my pastor. He was every black man that I love. His death represented the death of a million black men. Every death of a black man at the hands of injustice threatens black men everywhere.

If you’re reading this and you’re white, when was the last time you watched another white person die a violent death on your phone? I have watched more black men and women die on Twitter and Instagram than I can count on both hands. The careless tossing away of black lives, especially by those who are supposed to protect and serve, has turned into a monthly episode on social media.

We should not have to watch ourselves die over and over at the hands of the police. We should not be used to hearing “not guilty” when police are put on trial for our murders. We should not be used to finding out about police departments covering up gruesome murders at the hands of their police officers. We should not be used to grieving, but we are.

George Floyd’s death was not the first or the last gruesome murder of an innocent black man caught on tape. In 1961, the author James Baldwin said so poignantly, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost, almost all of the time.”

When I watched Floyd die, I watched my father die, I watched my brother die, I watched my cousin die, not for the first time, but the twentieth time. His death felt like another wave of grief and anger. That’s how it felt in 1961, and still feels today, to be a black person in America with any semblance of consciousness; it feels like a constant state of grief and anger that comes in waves.

George Floyd’s murder was a horrendous and disgusting show of the carelessness with which the police and society treat black bodies. What adds to the tragedy is that his story is not the first or last of its kind; I have friends and family members who have lost loved ones to the police, been injured by the police, or have lost quality of life because of the police, but their names were not placed after a hashtag because no one was there to record it.

For many black people, George Floyd’s murder and America’s response felt like a little too late awakening as we have been dealing with this treatment, specifically by the police, for generations. However, I am optimistic that those who fought for George Floyd will continue to fight with that same ferocity for our black brothers and sisters who are still alive.

Since last year, I have started to see a sense of urgency from the white majority to eradicate certain racist systems, which is amazing. However, it is important that black lives also matter even when it is not palatable and marketable for businesses and organisations.

Black lives matter when the victim is a criminal, or homeless, or disabled, or loud, or not nice. Black lives matter even when the victim is not crying out for his mother. Black lives matter even when there is no phone screen recording it.

Last year, I was proudly among one of the many applicants for law school; applications for college, law school, med schools, and other graduate schools were in record numbers in America, seemingly as a result of the number of systemic injustices we saw unfold. This fall, I will be beginning law school with an intent to work in prison, criminal justice, and broad human rights reform (which also are areas that are inherently racist in America).

Seeing the urgency of our youth to get involved in helping change the racist healthcare systems, racist criminal justice systems, racist public health systems, racist education systems has been refreshing and gives me hope that in generations to come, we will see changes in social thought leading to a more inclusive and empathetic society.

But the battle from last year is not over. The battle from 20 or 100 years ago is not over. In my opinion, police departments across America need to be uprooted and completely flipped on their heads to reveal to everyone the nasty racist history upon which they were created. Crime-control systems that focus on mental health resources, improving social interaction, creating job security and job opportunity, providing access to quality education, and creating community-led programming, etc. need to be implemented, as those are the aspects of society that actually decrease crime rates.

People must learn and listen to minority issues and treat others as they would like to be treated. Systems need to be created that do not benefit the white majority in a way that encourages indifference. Less than 5 per cent of lawyers are black, and less than 2 per cent are black women. Around 5 per cent of doctors are black; 7 per cent of teachers are black. There is a stark underrepresentation of black people in positions that affect some of the greatest changes in society. As more black and brown people are able to ascend to new heights in society, their influence will hopefully facilitate new changes in laws, practices, and social thought that can move us further away from systems of racism.

Moreover, the white majority have to share their platforms, listen to the needs of the minority, set aside their selfish and unilateral stances for the sake of advocating for those discriminated against. As those in power are mostly white men, we need their support and not their indifference. We need to continue making white people feel as uncomfortable about the racism that exists in America as we do so they too feel compelled to facilitate change.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Jun 2020 | News and features

Credit: Singlespeedfahrer/Petr Vodicka/Amy Fenton/Executive Office of the President/ Philip Halling/Isac Nóbrega/The White House

George Floyd. Dr Li Wenliang. Amy Fenton. JK Rowling. Edward Colston. Jair Bolsonaro. Donald Trump.

Love or loathe these people, the actions of each have opened a new debate in 2020. From the Black Lives Matter movement to the debate on sexuality, to the freedom of the press in the UK, to the role of Government and state actors hiding details of a public health emergency from their citizens.

If we have learnt anything at all from the turmoil that 2020 has given the world, it’s that free speech is vital; free expression is central to who we are and; that journalistic freedom is integral to the type of global society we aspire to live in.

Today, I’m joining the team at Index on Censorship as its new CEO. Index has spent the last half century providing a voice for the voiceless. Giving those who live under repressive regimes a platform to tell the world of their experiences and enabling artists to share their work with the world when they can’t share it with their neighbours.

Our work has never been more important. There have been over 200 attacks on media freedom across the globe, since the end of March this year, related to Covid-19. In the US alone there have been over 400 press freedom ‘incidents’ since the murder of George Floyd, including 58 arrests of journalists, 86 physical attacks and 52 tear gassings. In the UK, this weekend, on the streets of London we saw journalists attacked while reporting on a far-right demo in our capital.

My role in the months ahead is to highlight the threats to free speech, both in the UK and further afield, to celebrate free speech, to open a debate on what free speech should look like in the 21st century and most importantly to keep providing a platform for those people who can’t have one in their own country.

The editorial in the first edition of Index on Censorship in 1972, stated: There is a real danger… of a journal like INDEX turning into a bulletin of frustration. But then, on the other hand, there is the magnificent resilience and inexhaustible resourcefulness of the human spirit in adversity.

With you, the team at Index will continue to fight against the frustration while celebrating the magnificent resilience of the human spirit. And I can’t wait to get stuck in.

Ruth

PS Join us to protect and promote freedom of speech in the UK and across the world by making a donation.

6 Nov 2017 | Digital Freedom, News and features

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Facebook has received much criticism recently around the removal of content and its lack of transparency as to the reasons why. Although it maintains their right as a private company to remove content that violates community guidelines, many critics claim this disproportionately targets marginalised people and groups. A report by ProPublica in June 2017 found that Facebook’s secret censorship policies “tend to favour elites and governments over grassroots activists and racial minorities”.

The company claims in their community standards that they don’t censor posts that are newsworthy or raise awareness, but this clearly isn’t always the case.

The Rohingya people

Most recently, almost a year after the human rights groups’ letter, Facebook has continuously censored content related to the Rohingya people, a stateless minority who mostly reside in Burma. Rohingya have repeatedly been banned from Facebook for posting about atrocities committed against them. The story resurfaced amid claims that Rohingya people will be offered sterilisation in refugee camps.

Refugees have used Facebook as a tool to document the accounts of ethnic cleansing against their communities in refugee camps and Burma’s conflict zone, the Rakhine State. These areas range from difficult to impossible to be reached by reporters, making first-hand accounts so important.

Rohingya activists told the Daily Beast that their accounts are frequently taken down or suspended when they post about their persecution by the Burmese military.

Dakota Access Pipeline protesters

In September 2016 Facebook admitted removing a live video posted by anti-Dakota Access Pipeline activists in the USA. The video showed police arresting around two dozen protesters, although after the link was shared access was denied to viewers.

Facebook blamed their automated spam filter for censoring the video, a feature that is often criticised for being vague and secretive.

Palestinian journalists

In the same month as the Dakota Access Pipeline video, Facebook suspended the accounts of editors from two Palestinian news publications based in the occupied West Bank without providing a reason. There are no reports of the journalists violating the networking site’s community standards, but the editors allege their pages may have been censored because of a recent agreement between the US social media giant and the Israeli government aimed at tackling posts inciting violence.

Facebook later released a statement which stated: “Our team processes millions of reports each week, and we sometimes get things wrong.”

US police brutality

In July 2016 a Facebook live video was censored for showing the aftermath of a black man shot by US police in his car. Philando Castile was asked to provide his license and registration but was shot when attempting to do so, according to Lavish Reynolds, Castile’s girlfriend who posted the video.

The video does not appear to violate Facebook’s community standards. According to these rules, videos depicting violence should only be removed if they are “shared for sadistic pleasure or to celebrate or glorify violence”.

“Facebook has long been a place where people share their experiences and raise awareness about important issues,” the policy states. “Sometimes, those experiences and issues involve violence and graphic images of public interest or concern, such as human rights abuses or acts of terrorism.”

Reynold’s video was to condemn wrongful violence and therefore was appropriate to be shown on the website.

Facebook blamed the removal of the video on a glitch.

Swedish breast cancer awareness video

In October 2016, Facebook removed a Swedish breast cancer awareness campaign that had depictions of cartoon breasts. The breasts were abstract circles in different shades of pinks. The purpose of the video was to raise awareness and to educate, meaning that by Facebook’s standards, it should not have been censored.

The video was reposted and Facebook apologised, claiming once again that the removal was a mistake.

The Autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine explored the censorship of the female nipple, which occurs offline and on in many areas around the world. In October 2017 a Facebook post by Index’s Hannah Machlin on the censoring of female nipples was removed for violating community standards.

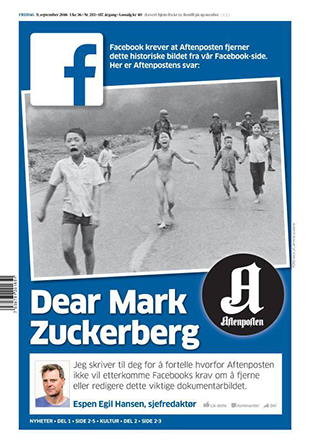

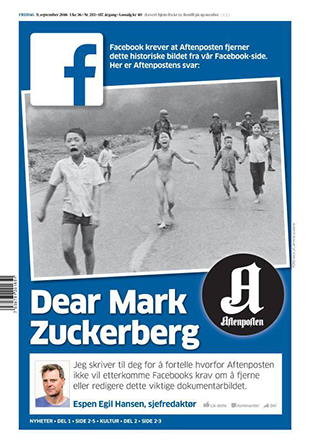

“Napalm girl” Vietnam War photo

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook removed an iconic photo from the Vietnam War. The photo is widespread and famous for revealing the atrocities of the war, especially on innocent people like children.

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook removed an iconic photo from the Vietnam War. The photo is widespread and famous for revealing the atrocities of the war, especially on innocent people like children.

In a statement made following the removal of the photograph, Index on Censorship said: “Facebook should be a platform for … open debate, including the viewing of images and stories that some people may find offensive, is vital for democracy. Platforms such as Facebook can play an essential role in ensuring this.”

The newspaper whose post was censored posted a front-page open letter to Mark Zuckerberg stating that the CEO was abusing his power. After public outrage and the open letter, Facebook released a statement claiming they are “always looking to improve our policies to make sure they both promote free expression and keep our community safe”.

Facebook’s community standards claim they remove photos of sexual assault against minors but don’t mention historical photos or those which do not contain sexual assault.

The young woman shown in the photo, who now lives in Canada, released her own statement saying: “I’m saddened by those who would focus on the nudity in the historic picture rather than the powerful message it conveys. I fully support the documentary image taken by Nick Ut as a moment of truth that capture the horror of war and its effects on innocent victims.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1509981254255-452e74e2-3762-2″ taxonomies=”1721″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook

A month earlier, in a serious blow to media freedom, Facebook