6 Feb 2014 | News, Religion and Culture, Russia

Human Rights Watch released a video documenting the treatment of LGBT Russians on 3 February ahead of the opening of the Sochi Winter Olympics.

Drawing a screen around the realities of life for Russian gays and lesbians, Russian president Vladimir Putin and the organizers of the Sochi Winter Olympic games are presenting a decidedly friendly face to international visitors.

Even though Sochi’s mayor, Anatoly Pakhomov, would prefer to believe “there are no gays” in his city, the mayor of the Olympic village, Elena Isinbayeva, offered to make LGBT athletes to feel welcome — despite her earlier homophobic comments. The girl band Tatu, most popular during the early 2000s when they exploited homoeroticism in their live appearances and videos, will perform at the opening ceremonies.

The real Russia has turned ugly and brutish toward its LGBT citizens.

The recent spate of homophobic violence has its roots in a controversial law that bars the promotion of non-traditional relationships as being equal to traditional relationships. While the law’s backers say they are protecting children, the effect has been to silence the push for gay rights by threatening fines for “homosexual propaganda.”

While official Russia will be demonstrating what it sees as tolerance in Sochi, a court in the city of Nizhniy Tagil will issue a ruling on the case of Elena Klimova – a young journalist who created a group on Vkontakte – Russia’s answer to Facebook. Klimova’s group, Children 404, contains letters from young LGBT people, who have been subject to physical and psychological attacks. Their letters to each other, according to Klimova, have been helping them cope with the pressure and continuing struggle for their rights. Klimova’s efforts to ease the isolation of LGBT children has drawn the ire of United Russia’s Vitaly Milonov, a proponent of the gay propaganda law, who has sued Madonna and been exposed as a bigot by Stephen Fry.

Klimova has also been active in raising concerns about the plight of a teen girl in the Bryansk region who has been put under administrative control by a local juvenile commission. Her crime? The girl openly identified “herself as a person with non-traditional sexual orientation and promote[d] information which misinforms minors about social equality of traditional and non-traditional relationship”. She will be monitored as if she were a criminal.

According to the latest Levada-Centre research, some 43% of Russian citizens consider homosexuality a bad habit, 38% reckon LGBT people should be “cured”, 47% say LGBT and heterosexuals are not socially equal and 73% approve the state’s effort to prevent public professions of an LGBT orientation.

The Russian Orthodox Church has done a lot to maintain these numbers.

Patriarch Kirill has repeatedly condemned equal marriage, saying in late January that marriage is “between a man and a woman, based on love, aimed at having children”. Kirill asked law makers to reflect his belief in drafting laws. Moscow Patriarchate’s spokesman Vladimir Legoida called equal marriage and homosexuality a sin in an interview to RIA-Novosti – the former Russian state news agency. Not to be outdone, Ivan Okhlobystin, an actor and former priest, said “gays should be burnt in ovens”.

In the meantime, on 3 February, the regional court of Kamchatka sentenced three people to 9-12 years in prison for the murder of a gay acquaintance.

Homosexuality was decriminalized in Russia in 1993. In 1999 it finally was excluded from Russian official list of mental illnesses. The change in people’s mind is still yet to come.

This article was originally published on 6 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

5 Feb 2014 | News, Russia

Several thousand protesters marched through central Moscow on 2 February 2014 to call for the release of 20 people who were arrested after clashes between police and demonstrators on 6th May of 2012. Photo: Nickolay Vinokurov / Demotix

Media will face increased restrictions in the build up to the Winter Games in Sochi as Russian president Vladimir Putin tries to rehabilitate a damaged domestic reputation, experts suggest.

Tighter controls on dissident media, more proactive use of state news outlets to mold public consensus, and obstacles to foreign reporters operating in the region can all be expected as the games begin on 7 February.

While Russian authorities have hailed the Games as a triumph, ongoing disputes over the payment of migrant workers, the environmental impact of Sochi’s intensive development, forced evictions of residents, intensive security measures, and Russia’s controversial gay propaganda law have all generated a domestic backlash that many believe is being deliberately ignored by state media. On 17 October, 2013, Roman Kuznetsov, a migrant worker from the Russian city of Orenburg who had helped build the Media Centre for the Sochi Olympic Games, sewed his lips shut with a needle and thread in protest against his employer’s failure to pay him several months of wages. He carried a sign that explained “Please help get reporters attention! I am not from around here”.

In an interview with select global media, Putin explained “I would like the participants, guests, journalists and all those who watch the Games on TV and learn about them from the mass media to see a new Russia, see its personality and its possibilities, take a fresh and unbiased look at the country”. Close restrictions recently imposed on press activity suggest otherwise. Only a small number of Olympic Events have been cleared for coverage by local journalists, including the arrival of IOC delegations and formal updates offered by federal officials. Access to government activities is granted only to the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company.

In a report produced by the Centre for the Protection of Journalists, a number of local journalists allege a more proactive media strategy in addition to direct censorship. Several reporters suggested that it was fairly common for media that receive funding to be directly censored by the administration. Local journalists also reported that the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company often stage interviews, and had been passing off closely scripted lines as dialogue with ordinary residents of Sochi. According to Russian Government website Zakupki, which details financial transactions at all levels of Russian government, the Sochi administration has distributed some 32,628.600 rubles (US$988,788) to 17 media organisations, including four television channels, six newspapers, one magazine, three radio stations, and one informational agency. It is not clear what form the funds took.

Aleksandr Valov, founder of BlogSochi, which seeks to document the impact of the Games on Sochi’s residents, explains “One begins to understand why Sochi media only talk about the government’s achievements and keep silent about the problems. The popular saying ‘He who pays the piper calls the tune’ comes to mind.”

International journalists covering Sochi have also been closely curtailed. Police from the Russian Republic of Adygea neighboring Sochi repeatedly stopped, detained, and threatened a two-person crew from Norway’s TV2- the country’s official broadcaster of the Olympic Games. At every stop and in detention, officials questioned the journalists aggressively about their work plans in Sochi and other areas, their sources, and in some cases about their personal lives, educational backgrounds, and religious beliefs. In several instances they denied the journalists contact with the Norwegian Embassy in Moscow. One official threatened to jail them both, the journalists told Human Rights Watch. Dutch photojournalist Rob Hornstra was denied a Russian visa in an apparent attempt to stop him from doing further work in the turbulent North Caucasus, and American journalist David Satter was forcibly expelled from the country in December.

Since beginning his first term as president in 2000, Vladimir Putin has carefully controlled his media presence, closing a number of independent media outlets and amalgamating others with state bodies, whilst tightly controlling the presence of foreign media. Professor Owen Johnson teaches at the School of Journalism at Indiana University, and has researched the role of media in Russia intensively. He offers a simple explanation for the recent expulsions ‘”While it would seem that this runs counter to other more positive actions by President Putin recently, this might be designed to make visiting journalists more cautious,” Johnson said. “Putin is less concerned about world public opinion than he is about his continued support in Russia.”

Domestic attitudes to Putin are changing fast, according to Mikhail Dmitriev, former director of Russia’s State Run Centre for Strategic Research. Over the past year discontent in the country at large has deepened and broadened, spreading across all social groups and ages. While support for Putin is stable in St. Petersburg and Moscow, where incomes remain high, fluctuating fortunes in Russia’s rural regions is starting to generate distrust. Dmitriev said the latest focus groups show that Putin is less associated with stability and more with uncertainty. His past achievements are becoming a distant memory, and his recent stunts, such as flying with cranes or diving for ancient amphorae, merely cause irritation.

The Sochi Games, Putin explained in a conference with journalists, will be an important global symbol of Russian achievement and resurgence. For Putin, well-managed domestic media coverage seems an important strategic component of his long term success and survival.

This article was originally posted on 5 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Jan 2014 | News, Religion and Culture

Fareed Zakaria (left) chaired two panels of LGBT activists at Davos. The first (above) consisted of Alice Nkom, Masha Gessen and Dane Lewis (Image: Twitter/@m_delamerced)

A panel of LGBT activists used the World Economic Forum last week to scrutinise recent homophobic laws passed by the Nigerian President, Goodluck Jonathan, despite rumours prior to the event suggesting it would be Putin who, for obvious reasons, would come under attack at the discussion.

Those taking part were flown into the event from around the world; Russian and American journalist Masha Gessen, Cameroonian lawyer Alice Nikom and J-FLAG Executive Director Dane Lewis were all present, as well as Human Rights Campaign President Chad Griffin, and Republican mega-donors Paul Singer and Dan Loeb.

Opening the breakfast discussion the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay said: “Two weeks ago President Jonathan of Nigeria signed into law a bill that criminalises, among other things, gay wedding celebrations, any public display of any same-sex affection, as well as the operating of gay clubs, businesses or organisations, including human rights organisations that focus on protecting the rights of LGBT people.”

Held rather ironically across the street from a discussion the Nigerian President himself was currently attending, Griffin followed suit: “Just to be clear what he signed, so everyone understands it in this room, it was already illegal to be LGBT but he further legalised it. You can be in prison for 14 years for simply being a gay person.

“Each one of you here would be subject to arrest because you’re in this room today: you’d go to prison for ten years. That’s what’s happening right now in that country and I bet you most people in that room don’t know what he’s just done.”

Putin’s name did manage to crop up in conversation and, not surprisingly, it was Gessen who had something to say.

She believes the Kremlin legitimately felt the LGBT community was the one minority it could beat up without fearing a backlash from the rest of the world- how wrong they were. The international reaction may have been slow to take off, she said, but the strong global response has come as a real shock to the Russian government.

“There is a reason why we talk about human rights and there is a reason why we talk about the protection of minorities, because minorities often do have to be protected from the majority, that’s the point,” Gessen said.

The ski resort of Davos, Switzerland welcomes around 2,500 of the world’s top business leaders, politicians, intellectuals and journalists each year to talk business. The singling out of countries or politicians for criticism during the conference is unheard of, according to Politico, which referred to the forum as a “week of political calm”.

This year’s conference came under the banner The Reshaping of the World: Consequences for Society, Politics and Business. Singer and Loeb, who organised the panel, reshaped the theme into a discussion about global sexuality and equality.

Loeb said: “We’re at the World Economic Forum. They say we’re here to make the world a better place. I think we need to take care of the injustices imposed on others in our efforts to make the world a better place.”

Griffin closed the talk by looking at the future of LGBT discussions at Davos, emphasising what an incredible start the first attempt at grabbing the world’s attention at the World Economic Forum was. But there were wishes that the intimate breakfast event would one day “be in the building across the street”.

Watch the full video of the discussion here.

This article was published on 30 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

14 Jan 2014 | News, Russia

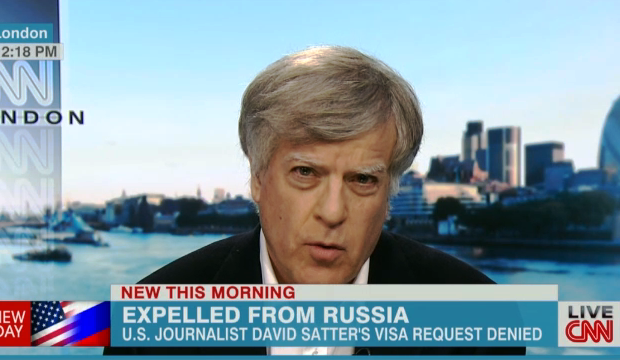

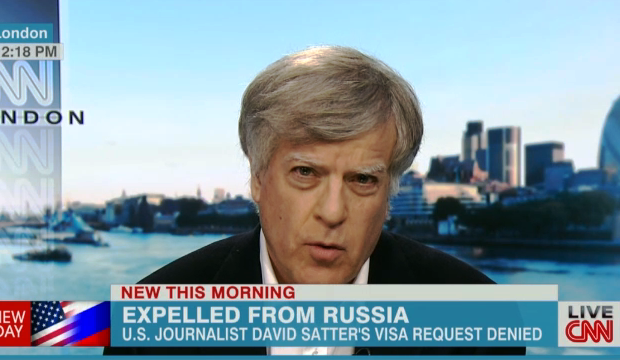

Fielding calls in the back of a London black cab, American journalist David Satter is a busy man.

Satter, who has reported on Soviet and Russian affairs for nearly four decades, was appointed an adviser to US government-funded Radio Liberty in May 2013. In September, he moved to Moscow. But at Christmas, he was informed he was no longer welcome in the country — the first time this has happened to an American reporter since the cold war.

Since Monday night, when the news of his expulsion from Russia broke, he’s been talking pretty much non stop, attempting to explain the manoeuvres which led to him being exiled from his Moscow home.

A statement issued by the Russian foreign ministry claims that Satter had violated Russian law by entering the country on 21 November, but not applying for a visa until 26 November.

Satter dismisses this as “nonsense”, saying he had been assured that a visa that had expired on 21 November would be renewed the following day, with no gap. As it happened, the visa was not renewed on time, “in order to create a pretext”, he tells Index.

To cut a short cut through a labyrinthine tale of bureaucracy: Satter says he left Russia in order to gain a new entry visa, which he could then exchange for a residency visa as an accredited correspondent for Radio Liberty.

He was repeatedly told this visa had been secured. Eventually, on 25 December, he was told that he had a number for a visa, but not the necessary invitation to accompany it. “Kafkaesque”, he calls it. The embassy official had never heard of this happening before. And, as Satter points out, he would not have been issued a number for a new visa in December if it had not been approved.

Eventually, he was told to speak to an official named as Alexei Gruby, who told him that “the competent organs” (code, Satter says, for the FSB) had decided that his presence in Russia was not desirable, language normally reserved for spies. “And now we see I have been barred for five years.”

“The point is, I urge you not to get caught up in their bureaucratic intrigues…the real reason was given to me, in Kiev, on 25 December.”

Is this just another example of FSB muscle flexing?

“Possibly. I’ve known them for a number of years, and I can’t always understand what they’re doing. Usually what they do is not very good…”

This is not Satter’s first brush with the Russian secret services. In a long career with the Financial Times, Radio Liberty and other outlets, he has experience of the KGB and its sucessor. “In 1979, they tried to expel me, accusing me of hooliganism. They once organised a provocation in one of the Baltic republics in which they posed as dissidents. I spent a couple of days with them, thinking I was with dissidents – I was really with the KGB. It’s a long history. It’s in my movie. We showed it in the Maidan [December’s anti-government protests in Ukraine]. Maybe they didn’t like that.”

Satter’s film, the Age of Delirium, is an account of the fall of the Soviet Union.

Is this expulsion a personal thing? Or a move against Radio Liberty? “It’s hard to say whether it’s me, or Radio Liberty, or both.”

Satter is concerned at leaving behind research materials and belongings in Moscow, saying it is likely his son, a London-based journalist, will have to go to Russia to collect them “unless they reverse their decision, which I hope they do”.

In spite of the recent amnesty that saw Pussy Riot’s Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina released from prison, as well as opposition figure Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the diagnosis for free speech in Russia is not good. Alyokhina dismissed her release as a “hoax”, designed to prove Putin’s power. Meanwhile, state broadcaster RIA Novosti has been dissolved and reimagined as “Rossia Segodnya” (“Russia Today” – no coincidence it bears the same name as the notorious English language propaganda station), with many fearing closer Kremlin control.

One Russian journalist I spoke to felt that, ahead of the Sochi games, the expulsion of Satter is a message to all journalists: no matter how experienced, well-known, and well-supported you are, you are still at the mercy of the authorities.

This article was posted on 14 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org