Comedy is everywhere

Novelist, playwright and short story writer Milan Kundera is one of the many Czech authors who, though they represent the best in their country’s contemporary literature, cannot publish their work in Prague. Acclaimed in France, where in 1973 he won a major literary prize for his last but one novel, and published in English, German, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Hebrew, Japanese and many other languages, he remains one of the 400 or more writers who are “on the index” in post-invasion, “normalised” Czechoslovakia.

Born in Brno forty-eight years ago, Kundera was until 1969 a professor at the Prague Film Faculty, his students including all the young film makers who were to bring fame to the Czechoslovak cinema in the sixties with such movies as The Firemen’s Ball, A Blonde in Love and Closely Observed Trains. In 1960 he published a highly influential essay, The Art of the Novel. Two years later the National Theatre put on his first play, The Owners of the Keys. Produced by Otomar Krejca, the play was an immediate success and was awarded the State Prize in 1963.

His first novel, The Joke, came out in 1967, being reprinted twice in a matter of months and reaching a total of 116,000 copies. This book, whose appearance was delayed by a long, determined struggle with the censor, opened the way to publication abroad, where Aragon called it one of the greatest novels of the century.

After the Soviet invasion Kundera was forced to leave the faculty, his work was no longer published in Czechoslovakia, all his books being removed from the public libraries. Since then, his works have only come out in translation. Life Is Elsewhere (see Index 4/1974, ppJ3-62) first appeared in Paris in 1973, where it won the Prix Medicis for the best foreign novel of the year. The French version of his latest novel, The Farewell Party, way published last year.

In 1975 Kundera was offered a professorship by the University of Rennes and obtained permission from the Czechoslovak authorities to go to France, which is now his second home. All his prose works now exist in English translation. (For an appraisal of his work, see Robert C. Porter’s article in Index 4/1975, pp.41-6). Unfortunately, The Joke – published by Macdonald in London and Coward McCann in New York in 1969 – was drastically cut without the author’s consent, forcing Kundera to write an indignant letter to the Times Literary Supplement, disclaiming all responsibility – an interesting case of a non-political, commercial censorship. The irony of the situation was certainly not lost on the author, who is a master of the genre. His collection of short stories, Laughable Loves (with a foreword by Philip Roth) and his other two novels have since been published by Knopf, and The Farewell Party has just been brought out by John Murray in London.

This selection of Kundera’s stimulating and often provocative views on such topics as the writer in exile, committed literature, the death of the novel, the nature of comedy, and so on, has been compiled by George Theiner.

Writing for translator

I am certainly in a rather odd situation. I write my novels in Czech. But since 1970 I have not been allowed to publish in my own country, and so no one reads me in that language. My books are first translated into French and published in France, then in other countries, but the original text remains in the drawer of my desk as a kind of matrix.

In the autumn of 1968 in Vienna I met a fellow-countryman, a writer, who had decided to leave Czechoslovakia for good. He knew that this meant his books would no longer be published there. I thought he was committing a form of suicide, and I asked him if he was reconciled to writing only for translators in future, if the beauty of his mother tongue had ceased to have any meaning for him. When I returned to Prague, I had two surprises in store for me: even though I didn’t emigrate, I too was forced from then on to write for translators only. And, paradoxical as it may seem, I feel it has done my mother tongue a lot of good.

Conciseness and clarity are, for me, what makes a language beautiful. Czech is a vivid, suggestive, sensuous language, sometimes at the expense of a firm order, logical sequence and exactitude. It contains a strong poetic element, but it is difficult to convey all its meanings to a foreign reader. I am very concerned that I should be translated faithfully. Writing my last two novels, I particularly had my French translator in mind. I made myself-at first unknowingly-write sentences that were more sober, more comprehensible. A cleansing of the language. I have a great affection for the eighteenth century. So much the better then if my Czech sentences have to peer carefully into the clear mirror of Diderot’s tongue.

Goethe once said to Eckermann that they were witnessing the end of national literature and the birth of a world literature. I am convinced that a literature aimed solely at a national readership has, since Goethe’s time, been an anachronism and fails to fulfil its basic function. To depict human situations in a way which makes it impossible for them to be understood beyond the frontiers of any single country is a disservice to the readers of that country too. By so doing we prevent them from looking further than their own backyard, we force them into a straitjacket of parochialism. Not to have one’s work published in one’s own country is a cruel lesson, but I think a useful one. In our times we must consider a book that is unable to become part of the world’s literature to be non-existent.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

Index on Censorship has been publishing articles on satire by writers across the globe throughout its 43-year history. Ahead of our event, Stand Up for Satire, we published a series of archival posts from the magazine on satire and its connection with freedom of expression.

14 July: The power of satirical comedy in Zimbabwe by Samm Farai Monro | 17 July: How to Win Friends and Influence an Election by Rowan Atkinson | 21 July: Comfort Zones by Scott Capurro | 24 July: They shoot comedians by Jamie Garzon | 28 July: Comedy is everywhere by Milan Kundera | Student reading lists: Comedy and censorship

Central Europe

As a Czech writer I don’t like being pigeon-holed in the literature of Eastern Europe. Eastern Europe is a purely political term barely thirty years old. As far as cultural tradition is concerned, Eastern Europe is Russia, whereas Prague belongs to Central Europe. Unfortunately, West Europeans don’t know their geography. This ignorance could be fatal, as indeed it has proved to be in the past. Remember Chamberlain in 1938 and his words about “a small country we know little about”.

The nations of Central Europe are small and far too well concealed behind a barrier of languages which no one knows and few study. And yet it is this very part of Europe which, over the past fifty years, has become a kind of crucible in which history has carried out incredible experiments, both with individuals and with nations. And the fact that those living in Western Europe have only very simplified notions, have never taken the trouble properly to study what is going on a few hundred kilometres from their own tranquil homes can, I repeat, be fatal to them.

From this Central Europe have come several major cultural impulses, without which our century would be unthinkable: Freud’s psychoanalysis; Schonberg’s dodecaphony; the novels of Kafka and Hasek, which have discovered a grotesque new literary world and the new poetry of the non-psychological novel; and finally structuralism, born and developed in Prague in the twenties, to become a fashion in West Europe thirty years later. I grew up with these traditions and have little in common with Eastern Europe. Forgive me if I seem to dwell on these ridiculous geographical details.

Small nations

Large nations are obsessed with the idea of unification. They see progress in unity. Even President Carter’s message to the inhabitants of outer space contains a passage expressing regret that the world is as yet divided into nations and the hope that it will soon come together in a single civilisation. As if unity were a cure for all ills. A small nation, in its efforts to maintain its very existence, fights for its right to be different. If unification is progress, then small nations are anti-progressive to the core, in the finest sense of the word. Big nations make history, small ones receive its blessings. Big nations consider themselves the masters of history and thus cannot but take history, and themselves, seriously. A small nation does not see history as its property and has a right not to take it seriously.

Franz Kafka was a Jew, Jaroslav Hasek a Czech – both members of a minority. When the First World War broke out, Europe was seized by a paroxysm of warlike nationalism, which did not spare even Thomas Mann or Apollinaire. In Franz Kafka’s diary we can read: “Germany has declared war on Russia. Went swimming in the afternoon“. And when, in 1914, Hasek’s Schweik learns that Ferdinand has been killed, he asks which one – the barber’s apprentice who once drank some hair oil, or was it the Ferdinand who collects dogshit on the pavement?

They say the greatness of life is to be found only where life transcends itself. But what if all transcendent life is history – which does not belong to us anyway? Is there only Kafka’s absurd

office? Only the daftness of Hasek’s army? Where then is the greatness, the gravity, the meaning of

it all? The genius of the minorities has discovered a world without gravity and greatness. Discovered its grotesqueness. Hegel’s concept of history -wise and ascending, like assiduous schoolgirls, ever higher on the staircase of progress – has been inconspicuously buried by Hasek and Kafka. In this sense we are their heirs.

Our Prague humour is often difficult to understand. The critics took Miloš Forman to task because in one of his films he made the audience laugh where they shouldn’t. Where it was out of place. But isn’t that just what it is all about? Comedy isn’t here simply to stay docilely in the drawer allotted to comedies, farces and entertainments, where “serious spirits” would confine it. Comedy is everywhere, in each one of us, it goes with us like our shadow, it is even in our misfortune, lying in wait for us like a precipice. Joseph K. is comic because of his disciplined obedience, and his story is all the more tragic for it. Hasek laughs in the midst of terrible massacres, and these become all the more un- bearable as a result. You see, there is consolation in tragedy. Tragedy gives us an illusion of greatness and meaning. People who have led tragic lives can speak of this with pride. Those who lack the tragic dimension, who have known only the comedies of life, can have no illusions about themselves.

When I came to France, the thing that astonished me most was the difference in national humour. The French are immensely humorous, witty, gay. But they take themselves and the world seriously. We are far more sad, but we take nothing seriously.

Committed literature

All my life in Czechoslovakia I fought against literature being reduced to a mere instrument

of propaganda. Then I found myself in the West only to discover that here people write about the literature of the so-called East European countries as if it were indeed nothing more than a propaganda instrument, be it pro- or-anti- Communist. I must confess I don’t like the word “dissident”, particularly when applied to art. It is part and parcel of that same politicising, ideological distortion which cripples a work of art. The novels of Tibor Dery, Miloš Forman’s films – are they dissident or aren’t they? They cannot be fitted into such a category. If you cannot view the art that comes to you from Prague or Budapest in any other way than by means of this idiotic political code, you murder it no less brutally than the worst of the Stalinist dogmatists. And you are quite unable to hear its true voice. The importance of this art does not lie in the fact that it accuses this or that political regime, but in the fact that, on the strength of social and human experience of a kind people over here cannot even imagine, it offers new testimony about the human conditions.

If by “committed” you mean literature in the service of a certain political creed, then let me tell you straight that such a literature is mere, conformity of the worst kind.

A writer always envies a boxer or a revolutionary. He longs for action and, wishing to take a direct part in real life, makes his work serve immediate political aims. The nonconformity of the novel, however, does not lie in its identification with a radical, opposition political line, but in presenting a different, independent, unique view of the world. Thus, and only thus, can the novel attack conventional opinions and attitudes.

There are commentators who are obsessed with the demon of simplification. They murder books by reducing them to a mere political interpretation. Such people are only interested in so-called “Eastern” writers as long as their books are banned. As far as they’re concerned, there are official writers and opposition writers – and that is all. They forget that any genuine literature eludes this sort of evaluation, that it eludes the Manichaeism of propaganda.

There are historical situations which open people’s souls the way you open a tin of sardines. Without the key offered to me by my country’s recent history, I would not, for instance, have been able to discover in Jaromil’s soul the incredible coexistence of the Poet and the Informer.

We have got into the habit of putting the blame for everything on “regimes”. This enables us not to see that a regime only sets in motion mechanisms which already exist in ourselves. A novel’s mission is not to pillory evident political realities but to expose anthropological scandals.

The death of the novel

Since the twenties, everyone seems to have been writing the obituary of the novel – the Surrealists, the Russian avant-garde, Malraux, who claims the novel has been dead since the time Malraux stopped writing novels, and so on and so forth. Isn’t it strange? No one talks about the death of poetry. And yet, since the great generation of Surrealists, I know of no truly great and innovatory work of poetry. No one talks about the death of the theatre. No one talks about the death of painting. No one talks about the death of music. Yet, since Schonberg, music has abandoned a thousand-year-old tradition based on tonality and on musical instruments. Varese, Xenakis . . . I am very fond of them, but is this still music? In any case, Varese himself preferred to speak about the organisation of sound rather than music. So, music may have been dead for several decades, yet no one talks about its demise. They talk about the death of the novel, though this is possibly the least dead of all art forms.

To speak of the end of the novel is a local preoccupation of West European writers, notably the French. It’s absurd to talk about it to a writer from my part of Europe, or from Latin America. How can one possibly mumble something about the death of the novel and have on one’s bookshelf A Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez? As long as there is human experience which cannot be depicted except in a novel, all conjectures about its having expired are mere expressions of snobbery. It is, of course, possibly true to say that the novel in Western Europe no longer provides many new insights and that for those we have to look to the other part of Europe and to Latin America.

I expect that all this talk of the death of the novel is due to the eschatological thinking of the avant-garde. Spurred on by revolutionary illusions, the avant-garde dreamed of installing a completely new art, a new era. If you like, in the spirit of Marx’s well-known saying about the prehistory and the history of mankind. From this point of view, the novel would belong to prehistory, while history would be ruled by poetry, in which all earlier genres would dissolve and vanish. It’s quite remarkable how this eschatological concept, utterly irrational though it is, has gained general acceptance, becoming one of the commonest clichis of the contemporary snob. He despises the novel, preferring to speak of’ a text’. According to him, the novel is a thing of the past (the prehistory of letters), and this in spite of the fact that the greatest strength of literature over the past 50 years has been in that very sphere-just take Robert Musii, Thomas Mann, Faulkner, Celine, Pasternak, Gombrowicz, Giinter Grass, Boll, or my dear friends, Philip Roth and Garcia Marquez.

The novel is a game with invented characters. You see the world through their eyes, and thus you

see it from various angles. The more differentiated the characters, the more the author and the reader have to step outside themselves and try to understand. Ideology wants to convince you that its truth is absolute. A novel shows you that everything is relative. Ideology is a school of intolerance. A novel teaches you tolerance and understanding. The more ideological our century becomes, the more anachronistic is the novel. But the more anachronistic it gets, the more we need it. Today, when politics have become a religion, I see the novel as one of the last forms of atheism.

When I was a boy I used to idealise the people who returned from political imprisonment. Then I discovered that most of the oppressors were former victims. The dialectics of the executioner and his victim is very complicated. To be a victim is often the best training for an executioner. The desire to punish injustice is not only a desire for justice, pure and simple, but also a subconscious desire for new evil…

Jacob knows all this when he thinks about others. He does not know it in relation to himself. So that all it needs is a single unguarded moment, when his reason takes a nap, and his subconscious dislike of people, his suppressed hatred, take over and an innocent girl dies. The more noble a person is, the darker the shadow of suppressed evil within.

A true novel always stands beyond hope and despair. Hope is not a value, merely an unproven supposition that things will get better. A novel gives you something far better than hope. A novel gives you joy. The joy of imagination, of narration, the joy provided by a game. That is how I see a novel – as a game. One of the characters in The Farewell Party occasionally has a halo round his head. The spa gynaecologist cures his patients by injecting his own semen and becomes the father of many children. Am I being serious, or is it just a joke? It is a game . . .

Of course, if the game is to be worthwhile, it must be played and must be about something serious. It must be a game with fire and demons. The game of the novel combines the lightest and the hardest, the most serious with the most light-hearted.

Milan Kundera is a Czech-born writer who has been living in exile in France since 1975.

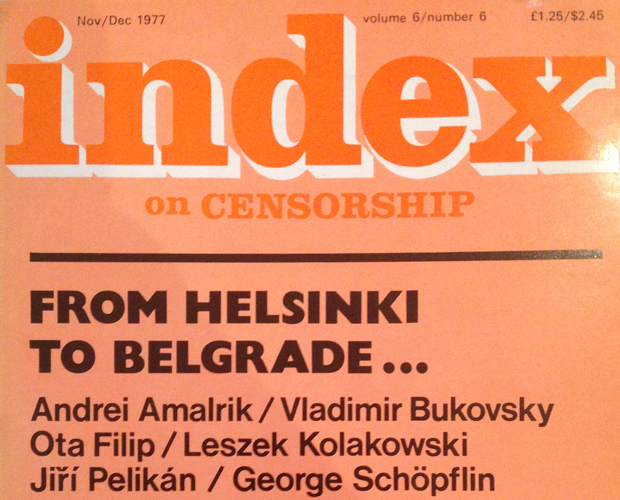

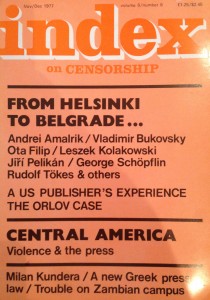

This article is from the November/December 1977 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]

This article is from the November/December 1977 issue of Index on Censorship magazine and is part of a series of articles on satire from the Index on Censorship archives. Subscribe here, or buy a single issue. Every purchase helps fund Index on Censorship’s work around the world. For reproduction rights, please contact Index on Censorship directly, via [email protected]