19 Mar 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, Turkey

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan (Photo: Philip Janek / Demotix)

In February, Turkish president Abdullah Gül prompted intense criticism when he approved restrictive new amendments to the law that regulates internet activity in Turkey, known as 5651. Since then, the Turkish government has continued to threaten internet freedom, placing added pressure on social media platforms. Earlier this month, prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan suggested that his government could block access to Facebook and Youtube after municipal elections on 30 March.

With over 34 million Facebook active users, Turkey is among the top 15 countries on the platform, and both the prime minister and Gül each have over four million Twitter followers. One day after Erdoğan’s statement during a live television interview, Gül countered that blocking access to social media was out of the question. Last week, Erdoğan followed by backtracking on his own comments.

Considering the already strained relationship that Erdoğan’s government has to social media, the turnaround on his comments is still no promise that there may be less restrictions on internet freedom to come in Turkey. In recent months, a number of wiretapped telephone recordings, allegedly of Erdoğan’s conversations, have been leaked onto social media platforms, including YouTube, SoundCloud and Vimeo, suggesting the prime minister’s meddling in corruption and intimidation of mainstream media. On the day that Erdoğan’s television interview aired, a new phone conversation was leaked onto YouTube, purportedly featuring the prime minister berating the media magnate Erdoğan Demirören for coverage in his daily Milliyet of a 2013 peace talk with Abdullah Öcalan of the separatist Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK).

Erkan Saka, an assistant professor at Istanbul Bilgi University and a researcher on new media, says

Erdoğan’s comments about Facebook and YouTube reflect his interest in controlling Turkish media. “Most of the mainstream media is already under their control, so this seems to be the only way now for people to express their opposition,” Saka said. With leaks appearing on video or audio sharing websites and spreading through Twitter and Facebook, social media platforms have become instrumental for circulating information related to the ongoing government corruption scandal.

Shutting down entire websites as Erdoğan suggested would mean going beyond the very recent amendments to law 5651 that make possible URL-based blocking of individual web pages ruled offensive, without restricting access to entire websites. YouTube was previously censored in Turkey for over two years after a video was posted on the site that was deemed insulting to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic. Earlier this year, Vimeo and SoundCloud were both temporarily shut down within Turkey following leaks that were published on those websites. Lawmakers from Erdoğan’s party, the AKP, have defended the controversial new version of 5651 because it allows for an alternative to restricting access to entire websites. Supporters of the law claim that with URL-based page blocking, defamatory content can instead be removed selectively.

In the run up to the elections at the end of this month, the recurring leaks and violent protests around Turkey threaten to tarnish Erdoğan’s popularity with voters. Responding aggressively in the televised interview, Erdoğan’s derision of social media platforms is personal, tactical, and aimed to discredit the websites as a threat to internet users’ safety. “We will not leave this nation at the mercy of YouTube and Facebook,” the prime minister said in his interview with journalists on broadcaster ATV. Calling the websites immoral, Erdoğan added, “they don’t have limits.” By casting social media websites as damaging to all internet users in Turkey, Erdoğan set the stage for potentially restricting access to those sites on moral grounds. Even after correcting his statement, Erdoğan’s suggestion that social media platforms are a source of danger is in line with his government’s use of internet filtering programs and ad campaigns that portray the internet as debauched to justify restricted access to content it considers harmful.

Aside from facing access restrictions, websites operating from Turkey are forced to comply with other laws that compromise their users’ privacy. Sedat Kapanoğlu, founder of the popular satirical, user-generated online dictionary Ekşi Sözlük, says internet companies in Turkey are put under pressure by laws requiring them to share user data. “A successful platform must create a free environment which protects its users’ rights. We are not able to do that. We are forced to provide IP addresses to prosecution even for completely legal content,” Kapanoğlu said.

One of the social media websites that Erdoğan singled out in his interview, Youtube, which is owned by Google, has an office in Turkey, while other large platforms like Facebook, SoundCloud, Vimeo, and Twitter do not.

Although he later rescinded his original statement, Erdoğan’s recent threat is alarming because it shows that in Turkey’s precarious climate for media independence, it might be plausible for his government to increase control of social media. With elections approaching this month, Erdoğan is himself coming under more pressure to win votes while facing a corruption scandal playing out on social media. The amendments to 5651 already make it easier for the Turkish Directorate of Telecommunication (TİB) to remove web pages from the internet. As more leaks continue to emerge, there is a lingering risk of new restrictions targeting social media platforms that have been at the centre of freedom of speech debates in Turkey.

This article was posted on 19 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Mar 2014 | Awards, News, Turkey

Turkey’s Gezi Park protests of 2013 saw a venting of frustration by many against what they saw as the increasingly authoritarian rule of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s AK party.

The protests were preceded by the run of Meltem Arikan’s play ‘Mi Minor’ in Istanbul from December 2012 to April 2013. Mi Minor used role play and social media to tell the story of a pianist using technology and social media to struggle against the regime in a fictional land called Pimina. In the month after the play ended, protests erupted in Istanbul, with social media playing a key role.

Arikan, already a prominent writer, found herself accused of fomenting rebellion and faced a co-ordinated campaign of abuse online from government supporters. She recently told Index on Censorship:

“When I was researching for Mi Minor [in 2011] I did everything I could so that the play wasn’t associated with Turkey, or the particular situation of Turkish politics, or any other actual country. It was a fictional dystopia. Mi Minor is an absurd play and it is too worrying to see how absurdity can be accused of being responsible for the reality of what happened in Gezi Park.”

“And the most worrying thing is that these accusations are still on-going. I wrote an absurd play and now my life has become more absurd than my play.”

Forced to flee because of the resulting pressures, Meltem Arikan now lives in the United Kingdom. She spoke with Index on Censorship about her nomination and the future of her work.

8 Mar 2014 | Azerbaijan News, News

International Women’s Day is a day to remember violence against women, the education gap, the wage gap, online harassment, everyday sexism, the intersection between sexism and other -isms, and a whole host of other issues to make us realise we’ve still got a long way to go. A day to demand continued progress, and a day to pledge to work to achieve it.

But it is also a day to celebrate. To appreciate the fantastic achievements that are made every day, everywhere, by women from all walks of life. It’s a day to be grateful to the women who dedicate their lives to fighting on the front lines to protect rights vital to us all. We want to shine the spotlight on women who have stood up for freedom of expression when it’s not the easy or popular thing to do, against fierce opposition and often at great personal risk. The following eight women have done just that. We know there are many, many more. Tell us about your female free speech hero in the comments or tweet us @IndexCensorship.

Meltem Arikan — Turkey

Meltem Arikan

Arikan is a writer who has long used her work to challenge patriarchal structures in society. He latest play “Mi Minor” was staged in Istanbul from December 2012 to April 2013, and told the story of a pianist who used social media to challenge the regime. Only a few months after, the Gezi Park protests broke out in Turkey. What started as an environmental demonstration quickly turned into a platform for the public to express their general dissatisfaction with the authorities — and social media played a huge role. Arikan was one of many to join in the Gezi Park movement, and has written a powerful personal account of her experiences. But a prominent name in Turkey, she was accused of being an organiser behind the protests, and faced a torrent of online abuse from government supporters. She was forced to flee, now living in exile in the UK.

I realised that we were surrounded, imprisoned in our own home and prevented from expressing ourselves freely.

Anabel Hernández — Mexico

Anabel Hernández (Image: YouTube)

Hernández is a Mexican journalist known for her investigative reporting on the links between the country’s notorious drug cartels, government officials and the police. Following the publication of her book Los Señores del Narco (Narcoland), she received so many death threats that she was assigned round-the-clock protection. She can tell of opening the door to her home only to find a decapitated animal in front of her. Before Christmas, armed men arrived in her neighbourhood, disabled the security cameras and went to several houses looking for her. She was not at home, but one of her bodyguards was attacked and it was made clear that the visit — from people first identifying themselves as members of the police, then as Zetas — was because of her writing.

Many of these murders of my colleagues have been hidden away, surrounded by silence – they received a threat, and told no one; no one knew what was happening…We have to make these threats public. We have to challenge the authorities to protect our press by making every threat public – so they have no excuse.

Amira Osman — Sudan

Amira Osman (Image: YouTube)

Amira Osman, a Sudanese engineer and women’s rights activist was last year arrested under the country’s draconian public order act, for refusing to pull up her headscarf. She was tried for “indecent conduct” under Article 152 of the Sudanese penal code, an offence potentially punishable by flogging. Osman used her case raise awareness around the problems of the public order law. She recorded a powerful video, calling on people to join her at the courthouse, and “put the Public Order Law on trial”. Her legal team has challenged the constitutionality of the law, and the trial as been postponed for the time being.

This case is not my own, it is a cause of all the Sudanese people who are being humiliated in their country, and their sisters, mothers, daughters, and colleagues are being flogged.

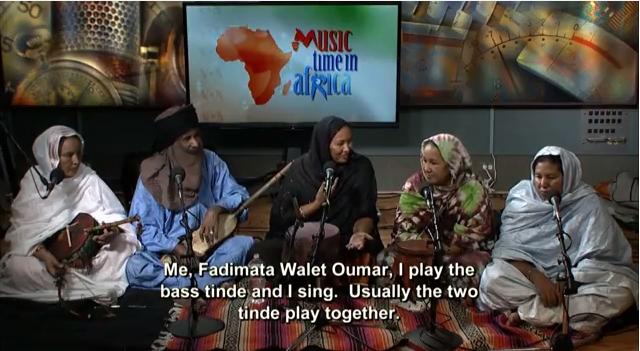

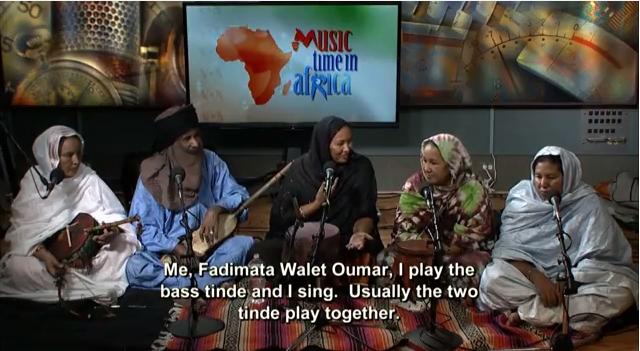

Fadiamata Walet Oumar — Mali

Fadiamata Walet Oumar with her band Tartit (Image: YouTube)

Fadiamata Walet Oumar is a Tuareg musician from Mali. She is the lead singer and founder of Tartit, the most famous band in the world performing traditional Tuareg music. The group work to preserve a culture threatened by the conflict and instability in northern Mali. Ansar Dine, an islamists rebel group, has imposed one of the most extreme interpretations of sharia law in the areas they control, including a music ban. Oumar believes this is because news and information is being disseminated through music. She fled to a refugee camp in Burkina Faso, where she has continued performing — taking care to hide her identity, so family in Mali would not be targeted over it. She also works with an organisation promoting women’s rights.

Music plays an important role in the life of Tuareg women. Our music gives women liberty…Freedom of expression is the most important thing in the world, and music is a part of freedom. If we don’t have freedom of expression, how can you genuinely have music?

Khadija Ismayilova — Azerbaijan

Khadija Ismayilova

Ismayilova is an award-winning Azerbaijani journalist, working with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. She is know for her investigative reporting on corruption connected to the country’s president Ilham Aliyev. Azerbaijan has a notoriously poor record on human rights, including press freedom, and Ismayilova has been repeatedly targeted over her work. She was blackmailed with images of an intimate nature of her and her boyfriend, with the message to stop “behaving improperly”. This February, she was taken in for questioning by the general prosecutor several times, accused of handing over state secrets because she had met with visitors from the US Senate. In light of this, she posted a powerful message on her Facebook profile, pleading for international support in the event of he arrest.

WHEN MY CASE IS CONCERNED, if you can, please support by standing for freedom of speech and freedom of privacy in this country as loudly as possible. Otherwise, I rather prefer you not to act at all.

Jillian York — US

Jillian York (Image: Jillian C. York/Twitter)

Jillian York is a writer and activist, and Director of Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF). She is a passionate advocate of freedom of expression in the digital age, and has spoken and written extensively on the topic. She is also a fierce critic of the mass surveillance undertaken by the NSA and other governments and government agencies. The EFF was one of the early organisers of The Day We Fight Back, a recent world-wide online campaign calling for new laws to curtail mass surveillance.

Dissent is an essential element to a free society and mass surveillance without due process — whether undertaken by the government of Bahrain, Russia, the US, or anywhere in between — threatens to stifle and smother that dissent, leaving in its wake a populace cowed by fear.

Cao Shunli — China

Cao Shunli (Image: Pablo M. Díez/Twitter)

Shunli is an human rights activist who has long campaigned for the right to increased citizens input into China’s Universal Periodic Review — the UN review of a country’s human rights record — and other human rights reports. Among other things, she took part in a two-month sit-in outside the Foreign Ministry. She has been targeted by authorities on a number of occasions over her activism, including being sent to a labour camp on at least two occasions. In September, she went missing after authorities stopped her from attending a human rights conference in Geneva. Only in October was she formally arrested, and charged for “picking quarrels and promoting troubles”. She has been detained ever since. The latest news is that she is seriously ill, and being denied medical treatment.

The SHRAP [State Human Rights Action Plan, released in 2012] hasn’t reached the UN standard to include vulnerable groups. The SHRAP also has avoided sensitive issue of human rights in China. It is actually to support the suppression of petitions, and to encourage corruption.

Zainab Al Khawaja — Bahrain

Zainab Al Khawaja

Al Khawaja is a Bahraini human rights activist, who is one of the leading figures in the Gulf kingdom’s ongoing pro-democracy movement. She has brought international attention to human rights abuses and repression by the ruling royal family, among other things, through her Twitter account. She has also taken part in a number of protests, once being shot at close range with tear gas. Al Khawaja has been detained several times over the last few years, over “crimes” like allegedly tearing up a photo of King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa. She had been in jail for nearly a year when she was released in February, but she still faces trials over charges like “insulting a police officer”. She is the daughter of prominent human rights defender Abdulhadi Al Khawaja, who is currently serving a life sentence.

Being a political prisoner in Bahrain, I try to find a way to fight from within the fortress of the enemy, as Mandela describes it. Not long after I was placed in a cell with fourteen people—two of whom are convicted murderers—I was handed the orange prison uniform. I knew I could not wear the uniform without having to swallow a little of my dignity. Refusing to wear the convicts’ clothes because I have not committed a crime, that was my small version of civil disobedience.

This article was posted on March 8, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Feb 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Turkey

Photo illustration: Shutterstock

Turkey stands at 154 out of 180 places on Reporters Without Borders 2014 Press Freedom Index.

As of December 2013, a total of 211 journalists were behind bars somewhere in the world. Almost one fifth of these alone were jailed in Turkey, making it the country with the most number of journalists imprisoned globally, and placing it behind countries with such as Iran and China.

In the past 18 months many renowned journalists have been removed from their positions due to direct and increasing government pressure on media organisations in an attempt to control the level of critical coverage.

The height of government pressure came during the June 2013 Gezi Park protests, in which 153 journalists were injured and 39 detained for just doing their job.

The majority of mainstream national TV channels failed to cover the initial protests for fear of backlash from the government. The recent approval of a new “internet law”, a law brought in on the grounds of protecting the privacy of private information, is seen by many as the latest step in a conscious effort by the government to control freedom of expression in Turkey.

In a 2007 article, Concentration of ownership, the fall of unions and government legislation in Turkey (£) journalism professor Christen Christensen argued that the enormous power of Turkish media owners leaves journalists powerless.

Journalists’ Trade unions are seen as “useless” in, leaving reporters vulnerable to economic and political pressure. In the same article, Christensen more importantly stated that while there has been an increase in penalties for crimes committed through print or mass media, simultaneously there is a lack of provisions securing the rights of journalists to report and discuss issues. The difficulty of carrying out the profession in Turkey is enhanced by the restrictions on access and disclosure of information and the vague language used to define defamation and insult.

Today, a high number of journalists have been charged under Turkey’s anti-terrorism legislation The law’s vague wording allows a broad interpretation what constitutes support for a terrorist organisation. Many high profile journalists, such as Nedim Şener, Ahmet Şık and Cumhuriyet’s Mustafa Balbay, were charged with involvement in the “Ergenekon plot” – an alleged shadowy conspiracy that authorities claim aimed to overthrow the government. These charges have been laced with claims of falsified evidence, discrepancies in computer records and doctoring of evidence.

The grounds for arrests have similarly been a cause for confusion, Şık, for example, was arrested for allegedly supporting Ergenekon when his unpublished book was allegedly found on internet news portal OdaTV computers, while evidence against Mustafa Balbay comprised of documents seized from his home and office, which he states were notes and recorded conversations with government and military officials conducted for the purpose of his journalism.

Again, the same anti-terrorist legislation has resulted in the arrest of several Kurdish journalists for what authorities say is dissemination of propaganda aligned with the banned Kurdish Worker’s Party, or PKK, and related organisations.

As political tensions in the country increase, vague legal frameworks continue to be the enemy of not only journalists, but also other groups, most significantly students – all of whom are being taught to fear the implications of expressing their thoughts. Despite there being talks on revising the anti-terrorism legislation to narrow its scope, it is clear that the major link between the above arrests is the presence of a voice of opposition and the lack of a strong legal framework to ensure a sound judicial process.

Today, journalists such as Nedim Şener, Ahmet Şık and Mustafa Balbay, still face jail time if sentenced and it is only with a revision of the law in question and the wider legal framework relating to journalists that the profession will be able to develop and fulfil its democratic role.

This article was published on 25 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org